This is the thirty-first in a series of posts about war tax resistance as it was reported in back issues of The Mennonite. Today we reach 1984.

The magazine helpfully summed up the current state of war tax resistance, particularly among American Christians, in its edition:

Military taxes: a continuing agenda in

“Were you able in 1983 to find the resources to support religious, charitable and peace efforts equal to the taxes you were required to pay for the military establishment?” The Friends Committee on National Legislation uses this question to encourage people to examine the consistency of their peace witness while filling out income tax forms.

In current military expenditures consumed 33 percent of federal appropriations, or 46 percent if the cost of past wars (interest on the national debt and veterans programs) is included, reports Delton Franz of Mennonite Central Committee Peace Section Washington Office.

During each Monthly Meeting (similar to an individual congregation) in the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting (similar to a conference body) was asked to examine this question: Is the voluntary payment of war taxes consistent with the Quaker peace testimony? When the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting convenes its annual session in , this question will be on the agenda.

Concern about “war taxes” is reaching beyond the traditional peace churches. The United Church of Christ and the United Methodist Church have adopted statements of support for members who conscientiously oppose payment of taxes for military purposes. The United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. has initiated a churchwide study on war tax resistance.

While the religious community in the United States has moved toward greater support for conscientious objection to paying taxes for military purposes, the Internal Revenue Service has beefed up its efforts to penalize tax “protests” of all kinds. An estimated 4,700 taxpayers were fined $500 each during for expressing their religious, moral or political views on their income tax forms. Congress enacted this automatic $500 fine as a provision of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of . The Internal Revenue Service began enforcing the penalty soon after its passage by Congress.

At least 30 people, including those of Mennonite, Quaker, Catholic and other religious backgrounds, are challenging the constitutionality of this regulation in court. Lawyers believe that the penalty violates freedom of speech and that the expression of religious convictions on income tax forms is not “frivolous.” Courts are expected to issue summary judgments (decision made by a judge only, no jury) in a number of cases in the coming year.

Internal Revenue Service officials invited Mennonite representatives to meet with them in to discuss the application of the penalty for “frivolous” returns. IRS officials told U.S. Peace Section staff that the penalty is a processing penalty, designed to protect the efficiency of processing millions of tax returns. People who have filled their tax forms out correctly and have simply not paid the full amount of taxes owed are not subject to this penalty. However, taking a “war tax” credit or deduction or writing other comments on the tax form itself can result in a penalty.

The IRS officials agreed that the World Peace Tax Fund bill would be a solution if it were enacted. Abatement of the penalties already imposed is highly unlikely, but senators who helped formulate the legislation remain concerned about its application against Mennonites and Quakers in particular.

The Fellowship of Reconciliation group in North Manchester, Ind., has organized a Tax Resister’s Penalty Fund to ease the financial burden on conscientious tax resisters. People can submit a request for financial assistance to cover interest and penalty charges resulting from not paying military tax.

If the request is approved, an appeal letter is sent to all people who have expressed interest in contributing to the fund. In this way, the cost of a $500 penalty could be distributed among 200 people if each paid only $2.50. In , 250 people were on the Tax Resister’s Penalty Fund mailing list.

In MCC U.S. Peace Section approved guidelines for a “War Tax Witness Relief Fund.” This fund was established to provide financial assistance to people within the MCC constituency who face hardship from court cases resulting from a war tax witness.

People in financial straits because they contributed the military portion of their taxes to a charitable organization and then had to face an IRS levy, property seizure, or garnishment of wages would also be eligible for assistance.

To date, no money has been budgeted for the U.S. Peace Section War Tax Witness Relief Fund and the existence of the fund has not been publicized. U.S. Peace Section, however, will consider aiding those who are unable to acquire assistance from their congregation or conference.

U.S. Peace Section continues to accept contributions of redirected telephone and federal income tax money to its “Taxes for Peace” fund. Donations to this fund have supported special projects and the ongoing work of U.S. Peace Section.

War tax resistance had apparently also reached the Netherlands:

“The payment of taxes in the service of our common life is a necessary and a good thing. It is therefore unusual and inappropriate to refuse tax payment,” begins a declaration printed in several national daily newspapers in the Netherlands on and signed by 69 Amsterdam area ministers, including at least seven Mennonites. The statement, pointing out the Dutch government’s agreement to place nuclear weapons in the Netherlands, goes on to say, “In this critical phase we consider tax objection as a necessary means of protest. We wish tax monies no longer to be misused to continue along this dead-end road.”

The edition brought readers up to date on the story of John Dyck, a Canadian war tax resister whose story had been introduced :

He pays for war tax resistance

Like the rest of us, John R. Dyck of Rosthern, Sask., files his tax return.

But unlike most of us, he sends Revenue Canada a check for only 90 percent of his unpaid taxes. And he includes a letter informing the Canadian government that, for reasons of conscience, a check for the balance has been sent to the Peace Tax Fund in Victoria, B.C. The second check represents the estimated portion of Canadian taxes designated for the military.

This is in that John and Paula Dyck quietly insisted on not having their taxes spent on bombs and guns. They believe that Christian non-resistance means more than simply refusing to fight in a war. It also means not paying others to arm and fight for you.

A small but growing number of Canadians are sending a portion of their taxes to be held in trust by the Peace Tax Fund. They are hoping that the Canadian government will recognize their conscientious objection to military taxes and provide an alternative.

As a retired pensioner, Dyck must calculate the taxes he owes and forward that amount with his income tax return. Every year he checks with Ernie Regehr at Project Ploughshares (a peace research group) on the exact percentage of Canada’s budget that goes to the Department of National Defense. Last year it was 10.5 percent. He subtracts the military percentage and encloses a letter informing Revenue Canada of his actions, his reasons and the number of his account at the Rosthern Credit Union.

“I tell them, ‘If you want it, take it.’ But I won’t send it myself.”

Consequences. Last year Dyck found out the hard way what happens when the government wants to collect unpaid taxes. He says he was prepared to accept the consequences of his actions, but not for the ruthless, impersonal way Revenue Canada operates.

One day the Credit Union manager showed him an official letter that had arrived that morning garnisheeing his account. His personal notice of the action did not arrive until a week later. And even though the credit union account held sufficient funds, a second bank account in Saskatoon was also garnisheed. Then, without notice, his two pension checks stopped coming.

The government ended up with $360 more than was due and Dyck has not heard from them since. Presumably his “credit” at Revenue Canada will be used to cover the taxes he won’t pay for .

When Dyck visited the Revenue Canada office in Saskatoon to ask why he had not received a notice about the diversion of his pension checks, he was treated rudely. “The man used some pretty rough language. He gave me the impression that he would walk over anyone to get the money.”

Although he can recall the money in the Peace Tax Fund trust account if he wishes, he would prefer to have that money used in a hoped-for court challenge, based on the new Canadian Charter of Rights. “On principle, I don’t mind paying twice,” he says.

The Conscience Canada organization, an outgrowth of the Peace Tax Fund Committee, expects such a challenge to cost at least $50,000.

Dyck himself is not inclined to get involved in a court case. He has had trouble finding a lawyer who is sympathetic. Besides, “the court route should be taken by some organization that has enough money and can do it right.”

What is Caesar due? John R. Dyck is not a man to get up on a soapbox and trumpet his cause. But the word gets around. There are Mennonites in his hometown who don’t agree with him and others who ignore him.

His pastor chooses his words carefully when talking about the subject. “I don’t suppose he has a great deal of support in the church; people feel we should obey the government.”

Dyck is now 70 years old. When asked why he has taken such a stand when others rest in quiet retirement, he begins to talk about a lifetime spent in church-related service, of the example of his parents, about the books he has read and the years spent overseas with Mennonite Central Committee in Paraguay, India, Korea and Jordan, where he observed the effect of Western militarism. “They all left their mark on me.” He is committed to a vigorous, active faith based on a personal experience of God’s salvation and presence.

John doesn’t mind if people disagree with his stand. “I don’t have any corner on the truth. I know what it is for me at this moment. A person should stay true to one’s convictions.”

About his critics he adds, “People say, ‘What do you think you’re doing?’ I know that. I have no illusions that anyone in Ottawa is listening — at the moment. It has to start small, and I want to support this movement.”

But aren’t we supposed to give to Caesar what is Caesar’s?

“Sure. But does Caesar deserve all he asks for?”

A letter to Revenue Canada from Annie Janzen of Victoria, B.C., indicated that she was joining John Dyck in his protest. “I object on conscientious grounds to my taxes being used for war purposes… I have sent 12.2 percent (of income tax owed to Revenue Canada) of the net federal tax payable to Conscience Canada.”

The following brief note appeared in the edition:

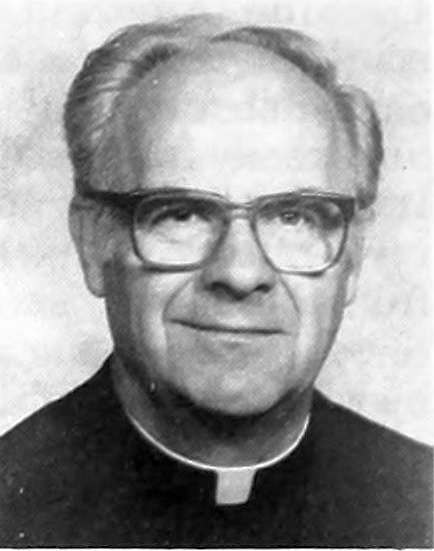

“Form 1040 is the place where the Pentagon enters all our lives and asks unthinking cooperation with the idol of nuclear destruction. I think the teaching of Jesus tells us to render to a nuclear-armed Caesar what that Caesar deserves: tax resistance.” These are the words of Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen (right), who two years ago decided to withhold half of his federal income tax and thereby helped launch a religious “war tax” resistance movement that is growing rapidly. According to the Internal Revenue Service, war tax resistance has increased nearly fivefold in the last three years. War tax resistance groups say that actual numbers are higher, that IRS tabulations miss many people, including those who simply don’t file or who don’t specify reasons for underpaying.

An article on the Church of the Brethren Annual Conference noted that it had “appointed a committee to study and recommend how Brethren should respond to the dilemma of paying for war through taxes.” And another note said that the Lutheran Peace Fellowship “issued a strong call to tax resistance by American Christians. LPF calls its action ‘a witness of faith against the false lordship of nuclear weapons and other instruments of mass destruction.’ ”

The edition gave an update on the Mennonite General Conference’s decision to stop withholding taxes from the paychecks of some war tax resisting employees. There wasn’t much new to report, except that the number of such employees had dropped from seven to five (“with some changes in personnel”).

In the edition, Donald E. Martin wrote about “sponsoring” children from war-torn areas, and noted that doing so “helped to cut down the amount of money we spent on ourselves and the amount of taxes we paid toward paying for war.”

There were also several passing mentions of war tax resistance here and there that I didn’t think were worth excerpting here.