This is the nineteenth in a series of posts about war tax resistance as it was reported in back issues of The Mennonite. Today we are up to 1972, a year in which there was an enormous amount of material about war tax resistance in the magazine.

In a weekend workshop was held for “people who seriously question the morality of paying all that Caesar demands.” The General Conference Mennonite Central District Peace and Service Committee was one of the sponsors. From the edition:

Workshop questions morality of war taxes

Christian response to war taxes was discussed by about 100 participants in a workshop in Elkhart, Indiana.

The weekend was sponsored by the Elkhart Peace Fellowship, the General Conference Mennonite Central District peace and service committee, and other regional church peace and service committees.

Michael Friedmann of the Elkhart Peace Fellowship said many of the participants felt the war tax question involved a shift in life style to reduce involvement in the military-industrial complex.

Al Meyer, a research physicist at Goshen College, Goshen, Indiana, suggested to the group that one does not start by changing the laws to provide legal alternatives, to payment of war taxes, but by refusing to pay taxes. We need to give a clear witness, he said.

Mr. Meyer did not oppose payment of war taxes because he was opposed to government as such, but because he did not give his total allegiance to government. He felt it was his responsibility to refuse to pay the immoral demands of government.

“No alternative will be provided by the federal government until a significant number of citizens refuse war taxes,” he said.

Art Gish, author of The new left and Christian radicalism, said draft resistance led logically to war tax resistance.

“If I won’t give the government my warm body, I shouldn’t give it my cold cash,” he said.

On , John Howard Yoder, president of Goshen Biblical Seminary, discussed the purposes of resisting tax payments. He felt the point is to make a clear moral witness. The goal should not be absolute resistance in keeping the government from getting the money. He said he would not give his money voluntarily, but would let the Internal Revenue Service know where they could find it.

Other participants felt tax refusal could be both witness to war and part of a larger movement to shift national priorities.

Mr. Gish discussed legal and illegal tax resistance. Goshen attorney Greg Hartzler emphasized that those who break tax laws should make their religious motivations clear if they want to avoid a severe sentence.

The workshop also discussed communities which are carrying the spirit of voluntary service into a total life style and are freer to develop a clear witness on the tax question.

Another topic was the World Peace Tax Fund, which a group in Ann Arbor, Michigan, is attempting to establish through a bill which it hopes will be introduced in Congress in . The bill would enable those who can demonstrate conscientious objection to war to put that portion of their taxes which would go to war into the fund. The fund would be used for such purposes as disarmament efforts, international exchanges, and international health.

Don Kaufman asked some “Crucial Questions on war taxes” in the edition:

- Is there a significant difference between fighting a war as a soldier and supporting it with taxes? “…why should the pacifist refuse service in the army if he does not refuse to pay taxes?” (Richard Gregg) Why should any person, on receipt of the government’s demand for money to kill, hurry as fast as he can to comply? Why pay voluntarily?

- What is the biblical or Christian basis for paying or not paying war taxes? What responsibility does an individual have for wars which are fought and financed by a government to which he makes tax payments? To whom is the Christian really responsible?

- When faced with a “war tax” situation, what should Christians do? Should Christians “…take their obligations toward government more seriously than their church obligations”? (Milton J. Harder) Unless followers of Jesus dissent from paying war taxes, how are government leaders to know that Christians are opposed to making war on other peoples whom God has created? What are the ways whereby we can keep dear our commitment to God and his love as revealed in Jesus, the Christ?

- Can a Christian obedient to God as the supreme Lord of his life continue simultaneously to “Pray for peace” and “Pay for war”? “How do you interpret Christ’s answer about the coin in relation to war tax payment? (See Mark 12:17.) Must Christians pay to have persons killed? What is Caesar’s? What is God’s?” (William Keeney) At what point does a government become satanic or demonic in that it demands what is God’s?

- Should Christians who object to paying war taxes wait with their protest until the whole Christian community agrees to do so?

- For the Christian who is opposed to war taxes, is it enough to simply refuse voluntarily payment of the money requested by IRS or should he put forth serious effort to prevent the government from obtaining the money?

- Isn’t the question of military taxation a reflection of the most formidable problem which every person or religious group must face in our time: Nationalism?

Ted Koontz of Harvard Divinity school attended the Mennonite Graduate Fellowship’s annual winter conference and “presented an analysis of reasons for war tax refusal for use in dialog with those who believe the war in Indochina is unjust but continue to pay war taxes.” (According to an article in the edition.)

The Commission on Home Ministries met in , and tax resistance came up:

The commission asked William Snyder, executive secretary of the Mennonite Central Committee, if MCC is discussing with other religious groups continuing the pacifist position beyond current “popular” opinions, and if MCC is pressing for an alternative fund for war taxes in light of the changing nature of warfare with finances as the primary resource.

Meetings to discuss war tax resistance were scheduled at three Mennonite churches in Kansas and Pennsylvania in and , according to an announcement in the edition. One of those meetings was covered as follows in the edition:

Western District discusses tax refusal, automated war

About fifty persons shared ways of protesting the use of their taxes for war at a meeting in Buhler, Kansas, sponsored by the Western District peace and social concerns committee.

After watching the slide set, The automated air war, produced by the American Friends Service Committee, participants discussed ways they are avoiding contribution to the war: refusing the telephone tax, refusing to pay income tax, investing in corporations which do not produce war materials, voluntary service, keeping income below the taxable level, and retirement.

Money and the weapons it buys, not the bodies of draft-age men, have become the primary resource for waging war, the group agreed. But individuals differed on the best way to influence government against war.

The Internal Revenue Service will attach bank accounts or auction personal property to collect delinquent income tax or telephone tax, and some persons questioned the effectiveness of refusal to pay when the government collects the money later with interest. Or are we simply called to be faithful? some asked.

Willard Unruh said, “It’s not the money that’s important; it’s the opportunity to express my opinion. I sent copies to Senators Dole and Pearson of my letter to the IRS. They both responded.”

Jonah Reimer suggested establishing a fund in Kansas into which persons refusing federal taxes could put an equivalent amount. “It would be an excellent way to witness,” he said.

The group also discussed attempts to place before Congress a bill to establish a government fund into which conscientious objectors to war could place their tax money, which would not be used for military purposes. Such a fund, however, would not necessarily reduce the amount of money going to the military.

Some persons objected to the fund, analogous to legal alternative service for conscientious objectors, saying that such a legal alternative would give approval to the evil of the military-industrial complex.

One man said, “Mennonites want special privileges. They want to come out of the war with a clear conscience. But we should want that clear conscience for everybody.”

“An increasing number of Mennonites are asking what it means to render to Caesar what belongs to him and in particular to render to God what belongs to him,” said Wesley Mast, Philadelphia, convener for the seminars. “Since war is increasingly becoming a matter of bombs and buttons rather than people, we need to ask what form Christian obedience takes.”

The other two meetings were covered in the edition. Excerpts:

Wesley Mast, Philadelphia, said, “The degree of openness on an issue as explosive as war taxes was amazing. We wrestled together first of all with the message of the Scriptures. Would Paul, for example, admonish us today to pay taxes, as he did the Roman Christians? Would he do the same to Christians in World War Ⅱ under Hitler? We noted that the times had already changed in the early church from the ‘good’ government in Romans 13 to the ‘beastly’ government in Revelation 13.”

The seminars also discussed the nature of the present war. Mr. Mast said the seminar participants heard that since World War Ⅱ the need for foot soldiers has declined 50 percent. Present war is becoming automated. “When they no longer need our bodies, how do we declare our protest?”

Another issue concerned tax dollars. “When over half of our taxes are used for outright murder, how can we go on sinning by supporting that which God forbids?”

With regard to brotherhood, “should the few who cannot conscientiously pay for war wait until others come along? How do we discern the Spirit’s leading in this and not make decisions on an individualistic basis?”

Howard Charles, Goshen Biblical Seminary, was resource teacher on biblical passages dealing with taxes. Other input was given by Melvin Gingerich and Grant Stoltzfus on examples of tax refusal from history. Mr. Mast presented options in payment and nonpayment of taxes. Walton Hackman broke down the present use of tax dollars, 75 percent of which go for war-related purposes.

“Mennonite collegians will meet to rap about the kind of lifestyle they want to adopt,” hiply noted an article in the edition. Among the topics on the agenda: “how to avoid complicity with militarism through paying taxes.”

“Shall we pay war taxes?” asked David L. Habegger in a lengthy article in the issue:

The continuation of the war in Southeast Asia calls upon us in the United States to review again our payment of taxes that go to support the war. In , the Council of Commissions meeting in Newton, Kansas, urged churches to consider the non-payment of a portion of their taxes. One of the district conferences passed a resolution chiding the council for being unbiblical. This response should have called for a mutual study of the question and this can still be done. It is the intention of the writer that this article should be a contribution toward the continuation of dialog on this topic.

The record of Jesus’ pronouncement on the paying of taxes is recorded in all three of the Synoptic Gospels (Matt. 22:15–22; Mark 12:13–17, Luke 20:20–26). This indicates the importance of this account to the early church.

The account tells of Pharisees’ and Herodians’ coming to ask a question of Jesus. They came the day after the cleansing of the temple. Their purpose was to discredit Jesus in the eyes of the people. Jesus had shown up the leaders of the temple and they were anxious to get back at him. This question is one of several that they used. Here the cooperation between the Pharisees and Herodians is strange. The Pharisees were opposed to the occupation by the Roman authorities, while the Herodians were enriching themselves by cooperating. They united because they both wanted Jesus out of the way.

The question of paying taxes brought different answers from these two groups. The Pharisees were nationalistic and were against any foreign occupation. They saw the payment of taxes as a symbol of their subjection to a heathen foreign power. They also hated using the coins with an imprint of Caesar’s likeness as it went against their interpretation of the second commandment. The Herodians were willing to see the taxes paid for they had improved their livelihood by their cooperation.

Thus the question would appear to be a legitimate one. Who was right? They recognized that Jesus was impartial to people and that if they could appeal to his sense of justice they might get him to make a judgment. On the surface their query seemed innocent enough. But they were laying a trap for Jesus.

The question was two-pronged. Jesus could be caught if he answered either “yes” or “no.” A “yes” would have disowned the people’s nationalistic hopes and given approval to the hated tax burden. The total taxes paid amounted to as much as 35 to 40 percent of their income. A “no” to the question would have made him liable to the charge of sedition and he could be reported to the Roman authorities. So either answer was one that was looked upon as a means of hurting Jesus and either discrediting him or doing away with him. Luke says clearly that they wanted to deliver Jesus up to the authority and jurisdiction of the governor (Lk. 20:20).

Mark says at the outset that the intent of the questioners was to entrap Jesus. We are also told that Jesus was aware of their hypocrisy, their seeming sincerity in asking a question with a hidden intent to trap him. On the basis of this information, to expect Jesus to reply with either a yes or a no would be to assume that Jesus was caught in their trap. The amazement of the questioners after Jesus’ reply indicates that Jesus did not give the kind of answer they expected.

Turning to the crucial issue, the Pharisees asked if it was lawful to give taxes to Caesar. The idiomatic rendering of this is “pay taxes.” Jesus replied that they should “pay back” to Caesar that which was his. Did Jesus see taxes as a return for benefits received? He probably did, but without sanctioning all that Caesar was doing. For it was Caesar who had provided for the making of the coin. But the paying back to Caesar statement does not stand alone and we cannot treat it as such. To it is added the phrase that we are to pay back to God what belongs to God. These two phrases need to be interpreted together. And there are several ways in which this can be done. What did Jesus mean?

First, some see the realm of Caesar and the realm of God as two side-by-side but separate and distinct realms, each having its own concerns and existence. The Christian lives in both realms and has a dualistic ethic. When it comes to killing, a Christian as a citizen of God’s kingdom will not kill. But as a citizen of this world he will be obedient to Caesar and take up arms. Many Christians see no inconsistency in reading the words of Jesus to mean this is the way they should live.

To some of us it is quite obvious that this is not the way Jesus taught us to live. We do not see him giving Caesar equal authority with God. Jesus warned that no man can serve two masters. So we reject the position that would say we should pay to Caesar regardless of the uses he makes of our money.

A second view is that the Kingdom of God is above the kingdoms of this world. God’s realm is holy and the worldly realm is sinful. According to this model, one would seek to live as much as possible within God’s realm. It might be necessary to be involved in the world to some extent but one would take no responsibility, such as voting or holding office. One would pay taxes to Caesar but would not see the money as purchasing any services. This has been the view of some Mennonites in the past. They asked nothing from the world and gave what was demanded except where it involved their personal lives. They let the governing authorities take full responsibility before God for the use of the taxes they paid. This position we also reject as an inadequate interpretation.

A third point of view sees the whole creation as belonging to God, with God acting in and through all men. Within the world are a number of states having separate existence but not autonomous existence for they are all under the judgment of God. What the rulers do, they are to do as ministers of God and it should always be according to God’s purposes. Their authority is a derived authority. Because the rulers of the states are not autonomous, they frequently seek to wield more power than given by God and so become demonic. Thus Caesar is not to be obeyed regardless of what he asks. We see fine examples of this in both the Old and New Testaments. When Caesar asks for more than God has set for him, the Christian must definitely refuse to grant it to him. Then the words, “We must obey God rather than men” are appropriate.

Knowing Jesus’ life of total obedience to the will of his Father, we have no doubt in saying that Jesus saw governing authorities as ruling under God. He told Pilate, “You would have no power over me unless it had been given you from above” (John 19:11). The Christians who received the revelation of Jesus Christ were told that those who are faithful unto death to their convictions would receive the crown of life (Rev. 2:10). It is to this third model that we look for guidance.

The words, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s” does say explicitly that there is an amount that is due a government. But we also hold that it says there are limits to what Caesar should ask. Jesus was not being asked about the payment of all taxes. A variety of taxes were levied by Caesar and the one Jesus was asked about was the annual poll tax that each male above fourteen years of age had to pay with the specific coin Jesus called for.

We need to see Jesus’ words as providing a generalization rather than a universal prescription. In moving from a general statement to a particular situation, we must always move carefully. Let me illustrate: we are told a person who is a guest should eat what is set before him (Luke 10:7). However, if a person is diabetic, it would not be right for him to eat food that would be harmful to his system. While we can say that Jesus supported the payment of taxes, we cannot thereby say that he favored the payment of every particular tax that a government might levy. We can all think of programs (such as the destruction of elderly and handicapped persons) which we would not be willing to support with our taxes. If that is the case, then we need to look seriously at what our taxes are doing in making war possible.

Living under a government that says it is responsible to the concerns of its citizens, we have an opportunity to witness by bringing our concerns to the government. A first step should be to write those who represent us and make the laws for our country. Stating our position in this manner is being a faithful witness. If the tax money is being used for purposes that are utterly contrary to what we understand to be the will of God, then we ought to consider the act of refusing to pay the tax. The purpose of this action is the desire to be faithful to the will of God as we know it and to help the rulers become aware of how they are overstepping the bounds of true ministers of God.

Paul in his letter to the Romans exhorts Christians to be obedient to the authorities. But he has already stated the principle that Christians should not be conformed to this world (12:1). Or as Phillips has translated it, “Don’t let the world around you squeeze you into its mold.” This calls for discernment on the part of the church. Can we as Christians continue to pray for peace while we pay for war?

The edition profiled two small Mennonite intentional communities in Kansas: the Fairview Mennonite House and The Bridge. The article noted:

[The Bridge] began forming at a Western District war tax workshop. David and Joanne Janzen, Randy and Janeal Krehbiel, and Steve and Wanda Schmidt were ready to stop paying taxes for war and to join into a brotherhood of shared income “to make our whole lives count for peace.”

Both intentional communities are a part of the voluntary service program of the General Conference Mennonite Church and follow the same financial pattern of self-support as the majority of other voluntary service units. All income is turned over directly to the voluntary service office in Newton, which reimburses the unit for such items as food, housing, travel, and medical expenses. Each individual receives $25 a month personal allowance.

Although critics of the intentional communities have accused them of using the voluntary service program as a tax dodge, members of the communities felt strong ties with their Anabaptist heritage and wanted to channel their resources to and through the church. But there are no apologies for not paying taxes. “We’re witnessing to the fact that the federal government is not using our money responsibly in its huge military expenditures,” said Ken [Janzen].

A member of the Love, Joy, Peace Community (Washington, D.C.) wrote a letter in response in which he wrote (in part):

The problem of war taxes is one which both Fairview House and The Bridge are addressing. It’s good to see people more concerned with “rendering to God what is his” (our whole lives), rather than being obsessed with Caesar and his temporal demands! We have long been passive, instead of active peacemakers. We pray for peace while we pay for war.

On , eight Boston Mennonites wrote in to say they’d started resisting:

Decision to withhold taxes

Dear Editor: As members of the Mennonite congregation of Boston, we are writing this letter to make public our decision to withhold a portion of our federal taxes, either income or telephone taxes. This decision came out of discussions with the entire congregation. We are doing this because our Christian consciences and our Mennonite backgrounds tell us the war in Southeast Asia is counter to the teachings of Christ. We have chosen to withhold our taxes because part of the responsibility for the war resides with those who willingly support it financially, regardless of what they believe.

Realizing this act will undoubtedly have a very small effect indeed on governmental policy, we hope it will in some way influence others into taking concrete actions which will demonstrate Christian love. Our friends and our families cannot help but react to our decision to withhold taxes.

The desired effect of our actions is not, however, the sole reason why we have chosen this form of protest. As conscientious objector status has become more automatic for Mennonites, refusal to pay war taxes has provided an additional way to demonstrate one’s Christian beliefs. Because we have only rough guesses as to the effects of our act, we accept as a matter of faith that this act will at least be a significant event in our Christian lives.

While we know the government will eventually collect our taxes, our intention to send an equal amount of money to the Mennonite Central Committee for Vietnam relief is a further Christian witness. It offers our alternative to war.

Jerry and Janet Friesen Regier,

Weldon and Rebecca Pries,

Ted and Gayle Gerber Koontz,

Dorothy and Gordon D. Kaufman.

The edition carried this news:

MCC notes increase in tax-refusal donations

An increasing number of people are sending war tax monies to Mennonite Central Committee, instead of paying them to the United States Government for military use, said Calvin Britsch, MCC assistant treasurer.

Contributions of tax money are of two kinds, Mr. Britsch said. More people are refusing to pay the federal tax levied on the use of telephones. This 10 percent tax is seen as a direct source for military expenditures. People who refuse this tax simply subtract the 10 percent from their telephone bill and send it instead to MCC.

We also receive contributions from people who refuse part of their federal income tax, Mr. Britsch said. Several people, for example, have withheld and have sent in as a contribution ten or 15 percent of their income tax in a symbolic protest against the Vietnam war and the whole United States military machine. Others who have had less than the total tax withheld send that remainder to MCC rather than to the Internal Revenue Service. We often get letters with tax refusal contributions explaining the individuals belief that, as a Christian, one cannot voluntarily, or without protest, pay money to be used for the destruction of human life.

Tax refusal contributions, unless otherwise designated, are usually applied to the MCC Peace Section budget, Mr. Britsch said.

The General Conference had asked the Commission on Home Ministries and the Commission on Overseas Mission to come up with some sort of repentance action, focused on the Vietnam War. They settled on a coordinated day of repentance, with other Mennonite and Brethren churches also joining in with a day of fasting and prayer. Included with the letter from the commissions announcing this was a confession of complicity, which said in part:

We recognize that though we cannot completely disassociate ourselves from the destruction and suffering the people of the United States are inflicting upon others, we continue to seek ways “to perform deeds worthy of (our) repentance.”…

As a church we have opposed war and worked for peace through programs of relief and service. Yet we share responsibility for the destruction in this way through our silence, through our profiting from a military economy, through our patronage of corporations with substantial defense contracts, and through our payment of the portion of telephone and IRS taxes used for war purposes. Much of this involvement is unintentional and may even be done without knowledge of the implications.

Ron Boese shared his letter to the IRS in the edition. Excerpts:

To pay income tax means to help buy the guns, airplanes, and bombs which continue daily to kill the men, women and children of Indochina. To pay this tax means to help build the nuclear weaponry which threatens the possibility of any joyful human life. To pay this tax is to help retire the mortgage of the atomic bombs which destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

So, instead of trusting my money to the federal government, I have directed my financial resources to organizations and individuals working for peace and justice.

Claus Felbinger, writing about the Anabaptist church in , said, “We are gladly and willingly subject to the government for the Lord’s sake, and in all just matters we will in no way oppose it. When, however, the government requires of us what is contrary to our faith and conscience — as swearing oaths and paying hangman’s dues of taxes for war — then we do not obey its command.” Living in the Anabaptist-Mennonite tradition, I feel that, rather than pay taxes, I must hear and respond to the cries of those who fall victim to the American war-making power.

I hope that you people working for the Internal Revenue Service will understand and accept my decision to follow conscience. I hope that you will also consider the contribution which your work of collecting war taxes makes to the suffering of our fellow human beings.

Accompanying this was a maudlin poem by another author, called “Confession” that began “I killed a man today / Or was it a woman or a child?” and went on to explain that his taxes paid someone to kill, in spite of all the other things he did to express his dislike for killing. But he was writing a letter to the IRS to tell them why he wouldn’t be paying “that part of income tax which is used for killing.”

The “Central District Reporter,” a sort of supplemental insert in the magazine, reported this from the district’s Peace and Service Committee:

Parents too have stopped being passive about peace. If son will not register, father will not pay the tax which keeps the army and any war going. All ages are learning more and more that there is no one way to give witness to convictions.

A letter to the editor from Jacob and Irene Pauls discussed their decision to redirect 64% of their federal income tax (“clearly designated for war”) from the government to the Mennonite Central Committee. They wrote: “The state has chosen an enemy, but we have no enemy. We do not accept the premise that the state can choose an enemy for us and force us to help annihilate the state’s enemy.”

From the edition:

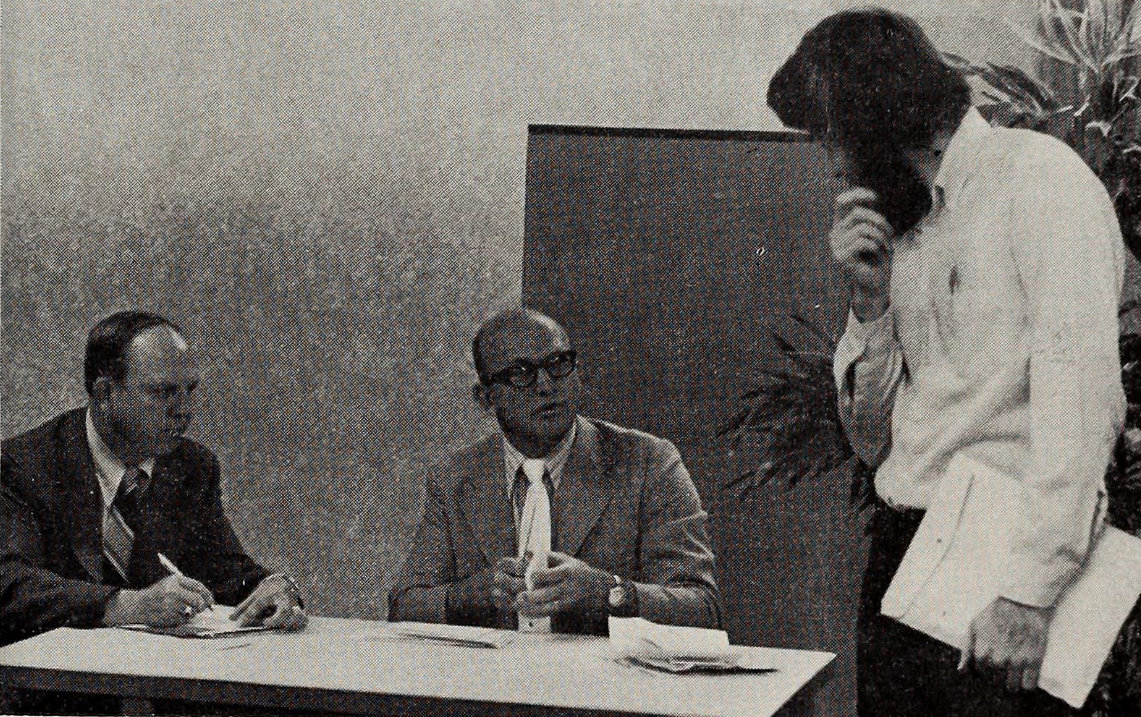

War tax resistance means sale of car. David Janzen, Newton, Kansas, at right, talks with Internal Revenue Service officials in Wichita as they open and record sealed bids for Mr. Janzen’s station wagon. The automobile was confiscated in for nonpayment of $31.32 of telephone excise tax which would have been used to carry on the war in Indochina. The officials read bids for one cent to $501, but refused to read bids for “one napalmed baby” and other “units of suffering” submitted by other war tax resisters and supporters. “All we’re interested in is the money,” said the IRS officer. “We’re interested in what the money buys,” replied Mr. Janzen. The intentional community of which he is a member bought back the station wagon.

A letter to the editor from Joan Veston Enz and former acting editor Jacob J. Enz argued for the “sanctity of life” pro-life position in the abortion debate, and also mentioned war tax resistance in passing:

There are some points at which it is necessary “to make a one-sided emotional commitment to one value” (our militaristic brethren in the church feel we do this on the war question — especially when we begin to urge withholding part of our income tax).

What was billed as a “‘Lamb’s war’ camp meeting” took place in . Sixty or seventy mostly youngish people, mostly but not all Mennonites, met to discuss “a life of sacrifice and aggressive peacemaking” as part of “a nonviolent army under the direction of God.” War tax resistance was one of the topics discussed, and the verse “gonna lay down my telephone tax, down by the riverside” was spliced in to the popular spiritual during an evening sing-along.

A letter to the editor from Robert W. Guth on the subject of war taxes again told the story of the excommunication of Christian Funk for paying taxes to the Continental Congress during the American revolutionary war, and of Andrew Ziegler’s “I would as soon go to war as pay the three pounds and ten shillings” response.

Preliminary results from the first Church Member Profile survey were revealed in a article. Excerpt:

In the United states… only 11 percent were uncertain about their position, should they be subject to the draft. Seventy-one percent would choose alternative service, an option acceptable to both the government and the church’s teaching in recent history.

However, 33 percent were uncertain about refusal to pay that proportion of their income taxes designated for the military. Fifty-five percent opposed nonpayment of war taxes.

The Mennonite Central Committee Peace Section held an assembly in . Some excerpts from the coverage of the assembly in The Mennonite:

Bill Londeree, a member of Koinonia Partners, Americus, Georgia, emphasized the personal response to affluence and militarism.

The Methodist Church, he said, has $40 million in investments in the top twenty-nine defense contractors — and sends out the antiwar slide presentation, “The automated air war.” Members of the Mennonite Church paid $87 million last year in war taxes and call themselves a “peace church.”

“This is schizophrenia of the first order,” Mr. Londeree said. “The greatest need is for examination of our own lives. Jesus’ first statement to us all is a call to repentance, to metanoia. This does not mean feeling sorry, but is a command to change.”

The assembly spent much of its time in small groups discussing the presentations and related topics, such as life style, the ideology of growth, war taxes, international economic relations, economic needs of church-related institutions, strategies for social change, new value orientations, and investments.