War tax resistance in the Friends Journal in

By , references to war tax resistance in the Friends Journal had become more casual and matter-of-fact, but also less urgent and less thorough.

In the issue, the pseudonymous history columnist for the Journal, “Now and Then,” examined the tradition of tax and tithe resistance in the Society of Friends:

Render Unto Caesar

For some years Friends have been aware of an anomaly in their traditional response to military requisitions. When they have been conscripted for military service, they have officially and in large numbers refused to go. Many governments have made provision for this expression of conscience. This has taken the form of allowing the payment for a substitute by the conscript, or some form of alternative service. Many Friends have accepted the latter.

But when our money is demanded, particularly as part of a more general tax, although we know its ultimate purpose is for war, only sporadically have Friends objected. Without recounting again all the data in our history in this matter, I inquire here why this curious contradictory situation has come to exist. Young men stubbornly refuse actual direct participation in war and do so with the sympathy of their parents, but the latter usually have contributed in money to the very cause to which their sons refused to contribute their bodies. And governments have usually provided no alternative to military payments.

A recent Yearly Meeting memorandum lists several of the reasons (excuses?) why Friends have abstained from refusing war taxes. Many of these reasons simply are practical considerations. But the first one on the list is the gospel phrase: “Render unto Caesar…”

The context of these words of Jesus is precisely that of a general Federal tax. They are therefore not taken out of context when applied to modern Federal taxation. Compared with them, there is nothing in the Gospels so explicitly quotable for or against military service. In former times… as well as today, this text has been repeatedly referred to by Friends in extenuation of their complicity by means of tax payment in the waging of war.

Why is this? Does it mean that Friends follow Jesus most readily when he seems to have left specific instructions, while where he is less specific they arrive at the stance of war resister in spite of this contrast? Undoubtedly, elsewhere in Quakerism we see evidence of Biblical literalism alongside of an almost contradictory dependence on the Spirit.

Or is the contrast between submitting to war taxes and refusal of war service due to the fact that the latter problem for a long time rarely arose, at least in England? While militia dues were refused as early as , compulsory military service scarcely began there until our own time.

Another Quaker financial refusal was early and widespread. That was of tithes levied on agricultural produce for “priests’ wages.” No single ground of resistance and persecution was so durable in our history. The money was for support of the official “hireling” ministers. Why was tax money to support war-making not equally obnoxious?

I wonder whether today “Render unto Caesar” can, as a saying of Jesus, bear the weight that we give it when without twinge of conscience we pay taxes of which so large a share finances war. At one time Friends — or at least some Friends — did refuse taxes levied exclusively for war costs. They distinguished them from what they called “mixed taxes.” It is not like Jesus to legislate on explicit social problems — and if he did, are we to take his words as rules for our own late generation? His followers did not always or in other respects blindly obey the government. When Caesar ordered pagan sacrifice in the following centuries, Christians would not offer even the token pinch of incense. In those days, Christians also refused participation in war. Under some circumstances, obedience to “the powers that be” seemed commendable; under others, Christians knew they must obey God rather than man.

Indeed, neither historical scholarship nor grammar leaves the intention of the Gospel saying quite so sweeping in its bearing. According to Luke, Jesus was accused of forbidding to give tribute to Caesar. Some modern students of the Gospels suspect that behind their present portrait lies a much more politically nonconformist Jewish subject of Rome.

The saying I quoted ends “…and unto God the things that are God’s.” Was not this the real thrust of original injunction? Perhaps Jesus never really answered the question, “Is it lawful to give tribute to Caesar or not? Shall we give or shall we not give?” And the apparent command to give tribute to Caesar may be only an analogy or a conditional clause, vindicating the major obedience — obedience to God.

In the same issue, David Nagle wrote in with his own lesson from history. He brought up the case of Joshua Maule, who at the time of the American Civil War was resisting a tax that was very similar to the recently-enacted Vietnam War income tax surcharge. Maule had written:

On this ground [the Scriptures] we believe the testimony stands and our discipline is established, which is clear against “paying taxes for the express purpose of war.” For war destroys that which is God’s, and invades the things which have not been committed to Caesar. And when the civil government commands us to co-operate in this work, either by personal service or payment of money for that express purpose, if we render unto God the things that are His, we should decline all voluntary payment of money demanded for the direct support of war, and be willing to suffer and bear whatever may be permitted to come upon us; rendering ourselves into the hands of the Lord, and trusting in him.

Nagle wrote: “I was impressed by the resemblance of this situation to ours today. The only significant difference seems to be that in the backsliders were in the minority and today few Friends have the courage to refuse to pay a tax intended expressly for the war effort, such as the present ten percent surtax. I ask that Friends give this concern the solemn consideration it deserves and seek the will of the Lord in regard to future actions.”

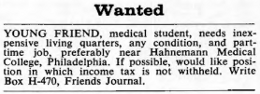

Also in that issue, Robert E. Dickinson wrote a curious piece, accompanied by photos, on “My Tax Refusal Furniture” — “a set of furnishings that easily could be moved or disposed of” that Dickinson designed and built after he was served an IRS seizure notice for “my property, including my furniture.”

When the authorities are at the door, the furniture can be demounted to flat slabs of plywood for ease in moving and storage.

The issue quoted from a statement issued by Hanover Monthly Meeting when it decided to start resisting the phone tax — “with regret but under compulsion of conscience” — and from statements issued by Alura and Donald Dodd, who had decided to pay their taxes into an escrow account rather than to the federal government.

In the issue, in an article mostly devoted to the Christian obligation of tithing, the issue of tax resistance sneaked in:

I suspect that the observance of tithing has fallen off partially as a result of the churches’ betrayal of their own stewardship. They have diverted to the needs of their own buildings and grounds that which should have been held in trust for all. They have faithfully received and have paid into the storehouses (or banks) but have stood guard to make sure that nothing but the interest flowed out. They have tied strings to their giving, withholding from those who do not meet with their approval and forgetting that God, whose stewards they should be, causes the rain to fall upon the just and the unjust alike.

Tithes, it seems to me, should not be given or withheld in an effort to bring pressure upon God or to coerce the workings of the Spirit. If we have lost faith that our own religious body is not administering its trust with true compassion for our troubled world, we may be well advised, not to renounce tithing, but to seek another storehouse — perhaps a church in the ghetto — where the Spirit may be less hedged about with anxiety and paternalistic caution.

And here, I believe, is the relationship — and the difference — between paying taxes and tithing. We should continue to render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, including obedience and respect as well as taxes, for so long as they are his due and his requirements are not in conflict with those of God. If the government turns away from righteousness, forsakes justice and mercy, and puts our taxes to ungodly uses instead of caring for all of its people, I believe we have the right to refuse and to reallocate to constructive causes that percentage of our income which is assessed as tax.

On the other hand, our allegiance to God is paramount. Under any and all circumstances we are required to render unto God that which is God’s including our tithes. However, just as we may need to consider withdrawing our financial support from a government that is not doing what a government is supposed to do, we may wish to consider reallocating our tithes if our own religious body fails to be responsive to the Spirit of Christ which is the foundation of our faith.

A report on the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s annual sessions in the same issue mentioned, but only in passing, that there had been “three called sessions on tax refusal and the Black Manifesto” over the past year.

A report on the General Conference for Friends in the issue reprinted a “query” that had been proposed by the “discussion group on tax refusal and tax avoidance”:

Have Friends considered their implication in the immoral war system through the payment of telephone excise and Federal income taxes, which are largely used for military purposes, and have they sought ways in which to make clear their testimony against such immorality by refusing, when possible, payment of such taxes and/or avoiding tax payments by changing their life style to live below or at a lower level of tax liability, bearing in mind that the spirit in which such action is taken is crucial and that divine guidance should undergird the individual’s response?

An article on individual spiritual growth in the issue casually included tax resistance as one of the issues a spiritual seeker might be expected to confront:

What do you do when you come to a stumbling point or dead end in your search? (Examples: Defining or identifying God, refusing to pay taxes, accepting the label “religious,” surrendering autonomy to a group, praying privately, and teaching one’s beliefs about religion to one’s children.)

That issue also reprinted a sarcastic notice from the Fifteenth Street (New York) Preparative Meeting’s newsletter:

Special offer for complacent Friends! The Peace and Social Action Program of New York Yearly Meeting is offering for sale two copies (paperback) of the Journal of John Woolman. These copies are unique in that all the radical passages have been removed by mechanical excision. They were cut to prepare a pamphlet of Woolman excerpts called, “John Woolman on Seeds of War and Violence in our Possessions, Consumption, Taxpaying, and Lifestyles.”

The special clearance price, only $19.95 a copy. Which is a bargain, considering that it saves you the trouble of removing these passages yourself!

The issue noted that the Saint Louis Monthly Meeting was administering an escrow account to accept money from Friends who were refusing to pay the Federal excise tax on phone service.

Don Kaufman’s book “What Belongs to Caesar?” was reviewed in the issue. The reviewer was sympathetic to the book’s thesis — that war tax resistance and Christianity are compatible — but thought the book “would be even more valuable if the author had felt as free to quote from the Bible as he was to quote from other books and articles.”