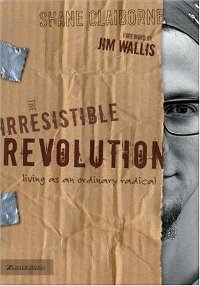

In The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical, Shane Claiborne tells the story of how he scavenged through all of the rubbish of American Christianity to find his best guess as to what Christ really called on his followers to believe and to do.

He thinks that many of the more extreme and difficult-to-swallow parts of the gospels are meant to be taken seriously: that the rich really should sell what they have and give the money to the poor, that Christians should hold everything in common and treat everyone as a brother or sister, that you should love your enemies, that you can have faith that God will provide for your needs.

He tries to live as though that were all good advice, and has helped to invent a sort of new, urban, service-oriented, community-focused, quasi-monasticism and evangelism, a bit in the Catholic Worker mode. Pursuing the “give a man a fish and he eats for a day; teach a man to fish and he eats for life” proverb, he writes: “We give people fish. We teach them to fish. We tear down the walls that have been built up around the fish pond. And we figure out who polluted it.”

The book is very much about what it means, or ought to mean, to be a Christian, and what form the Christian church ought to take. As a non-believer (to me, Christianity seems pernicious balderdash), I lacked the foundation necessary to appreciate much of this. That said, if Christianity were as Claiborne describes, it really would be a nice thing to have around, so I wish him luck.

Why does a nonbeliever like me end up poring through the writings of Christian seekers like Martin Luther King, Kierkegaard, Tolstoy, Ammon Hennacy, Augustine, Pierre Ceresole, and Shane Claiborne? At their best, such Christian writers have a desperate urgency to sculpt their lives according to their highest ideals, something that is rare enough in Christian circles but rarer still, it seems, in the secular world. In this way they can be pathfinding or pathmaking and worth paying close attention to even if you don’t share their faith.

Most Christianity I come across seems to be of two varieties: the church as a social club and the church as a comfortable validation of the congregation’s superiority. You go to church because that is where your friends and business associates and parents of your children’s friends go; or you go there to get fed the comfortable bullshit that confirms you’re on the right team and have the divine blessing for the life you wanted to live anyway. But then occasionally Christians like Hennacy, Ceresole, and Claiborne pop up who don’t fit in these categories but seem to be genuinely in awe of their God, challenged and compelled and frightened by the task ahead of them, and eager to learn how to get right even if taking Jesus at his word is uncomfortable and unpopular in the pews.

Amongst secular activists the same division seems to hold — but how few people fall in that small third category! Maybe this is partially because there are more Christians out there, so the small slice of that bigger pie looks bigger. But I think also there is more of a tradition of this sort of all-in transformation in Christianity, and also more structure to nurture it: Christians who are on a path of radically transforming their lives form communities of encouragement and mutual criticism and guidance — secular people on a similar path are usually on their own.