, the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee (NWTRCC) held its annual Fall gathering, this time hosted by the Catholic Worker house in Las Vegas. About twenty of us came from around the country to take care of organizational business, plot strategy, set goals, brainstorm, and swap stories.

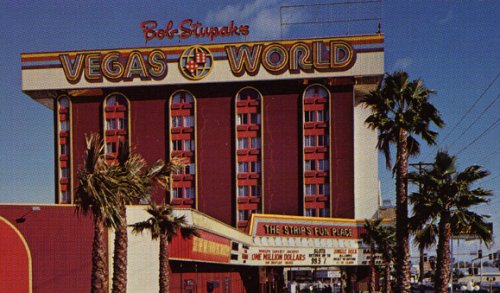

I used to come to Vegas from time-to-time to gamble & gawk, usually staying at Bob Stupak’s Vegas World and taking advantage of one of his complex coupon offers with which you could — if you had enough self-restraint in the casino — drive away from Vegas no poorer than when you arrived, with your room and much of your gambling paid for by Stupak.

According to one of our hosts at the Catholic Worker house, Stupak used to come down and volunteer at their soup kitchen from time-to-time as well. “He’d hand out cigarettes, too, which was very popular.” He even had his 50th birthday at the Catholic Worker kitchen. It’s a side of the polyester huckster I wouldn’t have guessed at.

On , before our meeting got started, a number of us joined up with some people from Nevada Desert Experience and Pace e Bene for a brief shift-change vigil at the Nevada Test Site.

While most of the weekend’s discussions were focused on a specific set of agenda items, night was dedicated to a more free-ranging discussion on the theme of “Money.” The seed for this discussion was an article Karen Marysdaughter had written in about how unchallenged attitudes about money and financial security prevent many people from considering war tax resistance, and discourage those who do consider it. She concluded:

I believe that long-held and firmly implanted notions about money, unless continually questioned and challenged, are likely to dominate people’s thinking about affluence, risk and self-worth. If we are to increase our numbers as a WTR movement, I think we need to include a critique of values and attitudes about money in our work and offer lots of explicit support for people who are changing their economic lifestyles in order to resist paying military taxes.

I took some notes on the conversation that we had, which I’ll share here in a fairly raw state:

One resister related his story of how his family had been resisting war taxes for years, but that the IRS had managed to seize over $100,000 in taxes, interest, and penalties. Not only did they lose this money, but because over the years they had been redirecting their tax payments to worthy causes, their overall payments were more than double their tax bill. Now, he says the family is practicing “the DON Method” instead.

On the one hand, he said, his family had not successfully kept any money from the government over the years, as the IRS had been successful in seizing the entire withheld amount. On the other hand, “it’s important to say ‘no’ to the government,” he believes, even if the government doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer.

Another resister noted, however, that in her Quaker community the idea that “the government will just end up getting the money in the end anyway” is a frequently-expressed reason why people don’t consider tax resistance.

One resister told of how his family uses untaxed state subsidies for their foster children as one way of staying under the tax line (but another asked if it is really ethical to accept cash subsidies from the same government you’re actively trying to avoid funding). Another resister said he hasn’t filed a tax return and works entirely in the cash economy, without credit cards or a bank account.

We talked a bit also about the distorted measure of affluence and security that we’re used to applying in the United States, and how even in the war tax resistance movement we sometimes describe the experiences of tax resisters using terms like “sacrifice,” and “suffering,” and “voluntary poverty” in ways that would seem ridiculous and obscene to the world’s poor.

As Karen Marysdaughter put it in her article: “For example, peace activists risk injury and death in Nicaragua, but can’t imagine living without health insurance. Our whole world risks nuclear holocaust, but voluntarily living on a low income is somehow too scary. As with affluence, we compare our financial risks to those of people who are more financially secure than we are, rather than to the vast majority of people in the world who really live on the edge.”

I recapitulated my observations about the taboo about sharing information about personal financial information I’ve noticed among my friends (see The Picket Line, ):

…it would be easier for many people to blog about the follies of their sex lives than about the line items in their budgets… everyone has a budget but nobody is supposed to really talk about it. If you pay too much attention to money it must be because you’re poor, or stingy, or greedy, or obsessed with money in a vulgar way, or something shameful like that.

[T]he part of our lives that we hide in this way is a big part of the lives we live. Somehow in the course of history, while we were acquiring tools like money and credit and capital and commerce to supplement and amplify our ways of living, we were also shoving a lot of how we live behind a veil.

The irony is that these same tools give us a convenient notation for quantifying and reconciling much of our incomes and outgoes, the heartbeats of our economic health — it’s as if someone has handed us binoculars and we responded by putting on a blindfold.

This taboo has some big disadvantages — it means that we don’t compare notes and learn from each other’s experiences, and also it means that we often do not look at our own economic behavior very closely…

[B]ecause we hide our true economic health from each other, we evaluate each other very superficially — we judge someone’s well-being by sizing up their bling because we know no better and aren’t supposed to ask. We envy people whose sparkling debts are crushing them and pity people who would rightly fight tooth and nail not to trade places with them.

It’s hard not to entertain conspiracy theories when confronting this. After all, it’s easier to make a profit off of customers who can’t tell whether or not they’re being ripped off, and it’s easier for a government to tax people who won’t bother to translate that lost money into lost time and energy because they don’t know any better.…

One resister noted that the collapse of family and community support for the elderly and infirm is one reason why people are increasingly fearful for their financial security on the one hand, and feel dependent on a government-provided safety net on the other.

All in all, this was a very good icebreaker conversation to have had on , though nothing much was decided or resolved. I’ll share my observations about the remainder of the meeting.