A new issue of NWTRCC’s newsletter is out. It includes a run-down of the latest news on the war tax resistance front, a report from the 25th anniversary gathering, and an article by Don Kaufman that focuses on the history of war tax resistance among American Mennonites.

Tax resistance in the “Peace Churches” → Mennonites / Amish → Don & Eleanor Kaufman

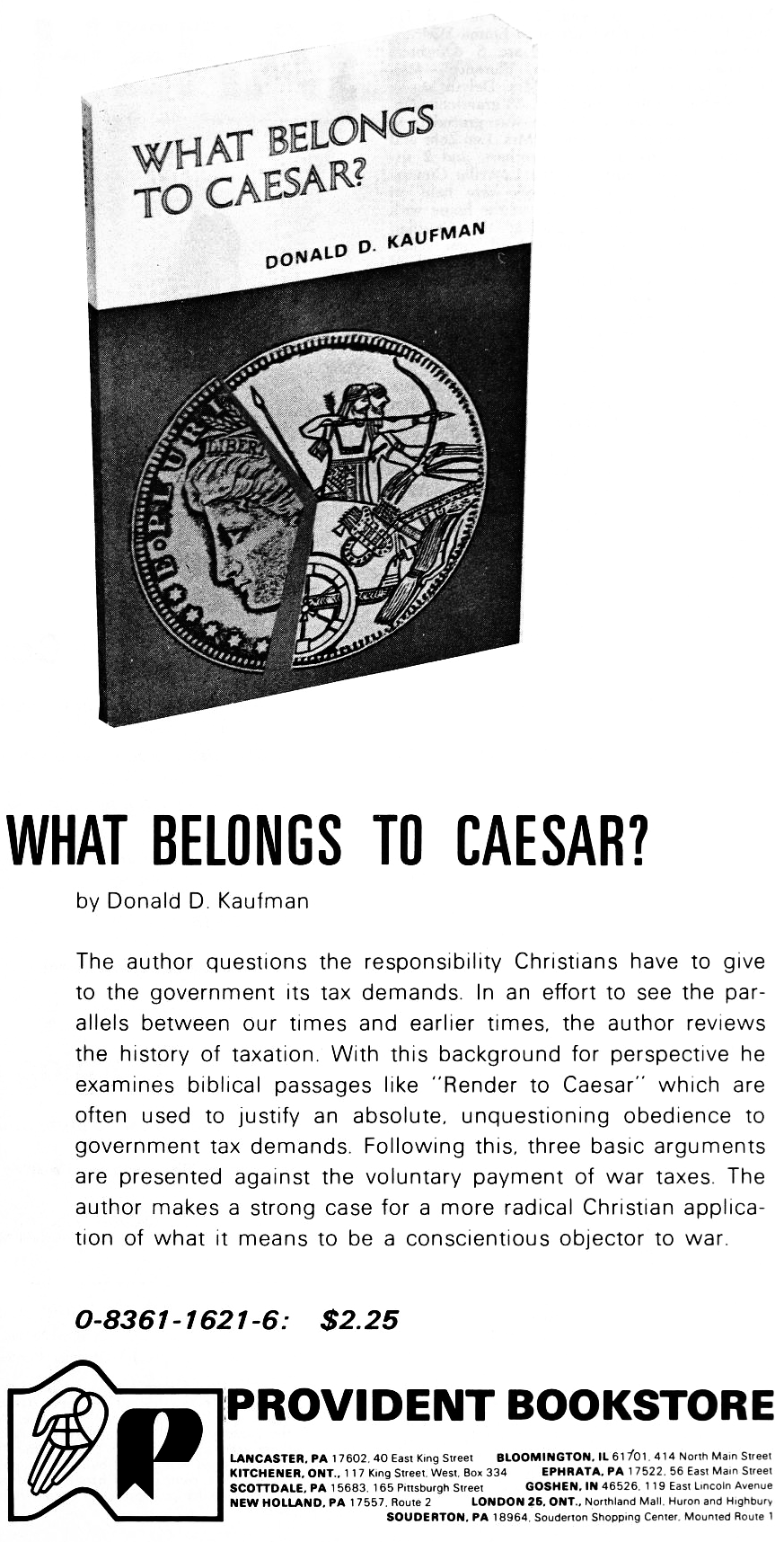

There’s a new issue of NWTRCC’s newsletter, More Than a Paycheck. It includes a brief review of We Won’t Pay! from Don Kaufman (author of The Tax Dilemma and What Belongs to Caesar):

Also in this issue:

- NWTRCC coordinator Ruth Benn reflects on the recent troubles in Gaza and encourages people to renew their pledge to boycott war taxes in .

- An update on the legal taxable income baseline for and on how much income is exempt from IRS levies, a note about how some banks are charging exorbitant processing fees when they submit to a levy, and some other news about tax policy and enforcement changes.

- Some news about the international conscientious objection to military taxation movement

- News about a celebration of the Wally Nelson Centenary to be held in Massachusetts, brief notices of a few books that have been published recently by war tax resisters, some information on the activities of War Resisters International, and another call to order some fundraising message scarves while the weather cooperates.

- Information about resources available to people promoting war tax resistance and/or the war tax boycott.

- News, including an update about Steev Hise’s tax resistance film project, the new NWTRCC “Speaker’s Bureau”, a request for nominations for people to fill two seats on the NWTRCC administrative committee that will open in , and a call to begin a discussion on whether or not it would be a good idea for NWTRCC to endorse the Religious Freedom Peace Tax Fund Act.

- An update from a new war tax resister, John Parrish who, along with his wife Kate, dipped their toes into the tax resistance pool with a token $50 resistance. They were surprised and alarmed when the IRS shark came for the toes and took the whole leg — assessing a $5,000 “frivolous filing” penalty on John and then another one on Kate! With the help of the folks at NWTRCC, their Congressman, and “the IRS Legislative Advocates” they managed to get the fines removed. John tells the story.

Some bits-and-pieces from around the web:

- Susan Balzer writes about Mennonite war tax resisters for the Mennonite Weekly Review. Some of the resisters mentioned: Tim Godshall, Willard and Mary Swartley, Ray Gingerich, Harold A. Penner, John and Janet Stoner, Albert and Mary Ellen Meyer, Don Kaufman, Titus and Linda Gehman Peachey, and Stan Bohn.

- Charles Merrill, who has been resisting taxes in protest against the government’s refusal to give equal legal recognition to same-sex marriages, is urging others to join him in a national “Tax Tea Party Revolt”:

A Tax Tea Party Revolt will be the only recourse available in the wake of efforts to not provide equal treatment to all citizens under law … This means gays, lesbians, bisexuals and transgender people will not be filing taxes April 15th.

- War tax resister NTodd Pritsky at Pax Americana takes note of the prosecution of a tax evader and wonders if this is going to be his eventual fate as well. Pritsky is resisting both federal and state taxes (as a war tax resister, he is protesting state complicity in the military industrial complex and in the wars via the state national guard). Fighting this battle on two fronts takes a lot of energy, and he’s not sure it’s worth it.

War tax resistance in the Friends Journal in

By , references to war tax resistance in the Friends Journal had become more casual and matter-of-fact, but also less urgent and less thorough.

In the issue, the pseudonymous history columnist for the Journal, “Now and Then,” examined the tradition of tax and tithe resistance in the Society of Friends:

Render Unto Caesar

For some years Friends have been aware of an anomaly in their traditional response to military requisitions. When they have been conscripted for military service, they have officially and in large numbers refused to go. Many governments have made provision for this expression of conscience. This has taken the form of allowing the payment for a substitute by the conscript, or some form of alternative service. Many Friends have accepted the latter.

But when our money is demanded, particularly as part of a more general tax, although we know its ultimate purpose is for war, only sporadically have Friends objected. Without recounting again all the data in our history in this matter, I inquire here why this curious contradictory situation has come to exist. Young men stubbornly refuse actual direct participation in war and do so with the sympathy of their parents, but the latter usually have contributed in money to the very cause to which their sons refused to contribute their bodies. And governments have usually provided no alternative to military payments.

A recent Yearly Meeting memorandum lists several of the reasons (excuses?) why Friends have abstained from refusing war taxes. Many of these reasons simply are practical considerations. But the first one on the list is the gospel phrase: “Render unto Caesar…”

The context of these words of Jesus is precisely that of a general Federal tax. They are therefore not taken out of context when applied to modern Federal taxation. Compared with them, there is nothing in the Gospels so explicitly quotable for or against military service. In former times… as well as today, this text has been repeatedly referred to by Friends in extenuation of their complicity by means of tax payment in the waging of war.

Why is this? Does it mean that Friends follow Jesus most readily when he seems to have left specific instructions, while where he is less specific they arrive at the stance of war resister in spite of this contrast? Undoubtedly, elsewhere in Quakerism we see evidence of Biblical literalism alongside of an almost contradictory dependence on the Spirit.

Or is the contrast between submitting to war taxes and refusal of war service due to the fact that the latter problem for a long time rarely arose, at least in England? While militia dues were refused as early as , compulsory military service scarcely began there until our own time.

Another Quaker financial refusal was early and widespread. That was of tithes levied on agricultural produce for “priests’ wages.” No single ground of resistance and persecution was so durable in our history. The money was for support of the official “hireling” ministers. Why was tax money to support war-making not equally obnoxious?

I wonder whether today “Render unto Caesar” can, as a saying of Jesus, bear the weight that we give it when without twinge of conscience we pay taxes of which so large a share finances war. At one time Friends — or at least some Friends — did refuse taxes levied exclusively for war costs. They distinguished them from what they called “mixed taxes.” It is not like Jesus to legislate on explicit social problems — and if he did, are we to take his words as rules for our own late generation? His followers did not always or in other respects blindly obey the government. When Caesar ordered pagan sacrifice in the following centuries, Christians would not offer even the token pinch of incense. In those days, Christians also refused participation in war. Under some circumstances, obedience to “the powers that be” seemed commendable; under others, Christians knew they must obey God rather than man.

Indeed, neither historical scholarship nor grammar leaves the intention of the Gospel saying quite so sweeping in its bearing. According to Luke, Jesus was accused of forbidding to give tribute to Caesar. Some modern students of the Gospels suspect that behind their present portrait lies a much more politically nonconformist Jewish subject of Rome.

The saying I quoted ends “…and unto God the things that are God’s.” Was not this the real thrust of original injunction? Perhaps Jesus never really answered the question, “Is it lawful to give tribute to Caesar or not? Shall we give or shall we not give?” And the apparent command to give tribute to Caesar may be only an analogy or a conditional clause, vindicating the major obedience — obedience to God.

In the same issue, David Nagle wrote in with his own lesson from history. He brought up the case of Joshua Maule, who at the time of the American Civil War was resisting a tax that was very similar to the recently-enacted Vietnam War income tax surcharge. Maule had written:

On this ground [the Scriptures] we believe the testimony stands and our discipline is established, which is clear against “paying taxes for the express purpose of war.” For war destroys that which is God’s, and invades the things which have not been committed to Caesar. And when the civil government commands us to co-operate in this work, either by personal service or payment of money for that express purpose, if we render unto God the things that are His, we should decline all voluntary payment of money demanded for the direct support of war, and be willing to suffer and bear whatever may be permitted to come upon us; rendering ourselves into the hands of the Lord, and trusting in him.

Nagle wrote: “I was impressed by the resemblance of this situation to ours today. The only significant difference seems to be that in the backsliders were in the minority and today few Friends have the courage to refuse to pay a tax intended expressly for the war effort, such as the present ten percent surtax. I ask that Friends give this concern the solemn consideration it deserves and seek the will of the Lord in regard to future actions.”

Also in that issue, Robert E. Dickinson wrote a curious piece, accompanied by photos, on “My Tax Refusal Furniture” — “a set of furnishings that easily could be moved or disposed of” that Dickinson designed and built after he was served an IRS seizure notice for “my property, including my furniture.”

When the authorities are at the door, the furniture can be demounted to flat slabs of plywood for ease in moving and storage.

The issue quoted from a statement issued by Hanover Monthly Meeting when it decided to start resisting the phone tax — “with regret but under compulsion of conscience” — and from statements issued by Alura and Donald Dodd, who had decided to pay their taxes into an escrow account rather than to the federal government.

In the issue, in an article mostly devoted to the Christian obligation of tithing, the issue of tax resistance sneaked in:

I suspect that the observance of tithing has fallen off partially as a result of the churches’ betrayal of their own stewardship. They have diverted to the needs of their own buildings and grounds that which should have been held in trust for all. They have faithfully received and have paid into the storehouses (or banks) but have stood guard to make sure that nothing but the interest flowed out. They have tied strings to their giving, withholding from those who do not meet with their approval and forgetting that God, whose stewards they should be, causes the rain to fall upon the just and the unjust alike.

Tithes, it seems to me, should not be given or withheld in an effort to bring pressure upon God or to coerce the workings of the Spirit. If we have lost faith that our own religious body is not administering its trust with true compassion for our troubled world, we may be well advised, not to renounce tithing, but to seek another storehouse — perhaps a church in the ghetto — where the Spirit may be less hedged about with anxiety and paternalistic caution.

And here, I believe, is the relationship — and the difference — between paying taxes and tithing. We should continue to render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, including obedience and respect as well as taxes, for so long as they are his due and his requirements are not in conflict with those of God. If the government turns away from righteousness, forsakes justice and mercy, and puts our taxes to ungodly uses instead of caring for all of its people, I believe we have the right to refuse and to reallocate to constructive causes that percentage of our income which is assessed as tax.

On the other hand, our allegiance to God is paramount. Under any and all circumstances we are required to render unto God that which is God’s including our tithes. However, just as we may need to consider withdrawing our financial support from a government that is not doing what a government is supposed to do, we may wish to consider reallocating our tithes if our own religious body fails to be responsive to the Spirit of Christ which is the foundation of our faith.

A report on the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s annual sessions in the same issue mentioned, but only in passing, that there had been “three called sessions on tax refusal and the Black Manifesto” over the past year.

A report on the General Conference for Friends in the issue reprinted a “query” that had been proposed by the “discussion group on tax refusal and tax avoidance”:

Have Friends considered their implication in the immoral war system through the payment of telephone excise and Federal income taxes, which are largely used for military purposes, and have they sought ways in which to make clear their testimony against such immorality by refusing, when possible, payment of such taxes and/or avoiding tax payments by changing their life style to live below or at a lower level of tax liability, bearing in mind that the spirit in which such action is taken is crucial and that divine guidance should undergird the individual’s response?

An article on individual spiritual growth in the issue casually included tax resistance as one of the issues a spiritual seeker might be expected to confront:

What do you do when you come to a stumbling point or dead end in your search? (Examples: Defining or identifying God, refusing to pay taxes, accepting the label “religious,” surrendering autonomy to a group, praying privately, and teaching one’s beliefs about religion to one’s children.)

That issue also reprinted a sarcastic notice from the Fifteenth Street (New York) Preparative Meeting’s newsletter:

Special offer for complacent Friends! The Peace and Social Action Program of New York Yearly Meeting is offering for sale two copies (paperback) of the Journal of John Woolman. These copies are unique in that all the radical passages have been removed by mechanical excision. They were cut to prepare a pamphlet of Woolman excerpts called, “John Woolman on Seeds of War and Violence in our Possessions, Consumption, Taxpaying, and Lifestyles.”

The special clearance price, only $19.95 a copy. Which is a bargain, considering that it saves you the trouble of removing these passages yourself!

The issue noted that the Saint Louis Monthly Meeting was administering an escrow account to accept money from Friends who were refusing to pay the Federal excise tax on phone service.

Don Kaufman’s book “What Belongs to Caesar?” was reviewed in the issue. The reviewer was sympathetic to the book’s thesis — that war tax resistance and Christianity are compatible — but thought the book “would be even more valuable if the author had felt as free to quote from the Bible as he was to quote from other books and articles.”

War tax resistance in the Friends Journal in

War tax resistance was a frequent topic in the issues of Friends Journal in , though there was still no consensus about how to go about it, and there was a lot of hesitance among Quaker institutions about how strongly to endorse it.

The issue was another special issue devoted to the peace testimony, which might as well have been a special issue on war tax resistance for how frequently it was mentioned. Clearly by this time, there was no talking about peace work without talking about war tax resistance.

an illustration by Duncan Harp, from the issue of Friends Journal

Editor Ruth Kilpack opened the issue. She noted:

I see the billions of dollars (including taxes from my own earnings) being poured into the “defense” budget. I hear of vastly increased crime and see the wanton waste everywhere, much of it the direct legacy of our last war; I remember the lives still festering in military hospitals, the suffering from the wounds of war both here and across the world.

But now, there is a handful of people who are beginning to take a new view of war and war-making, realizing that it takes place not only when the bombing and shelling begin, but in the will of the people who make — or allow — it to happen. War-making must be paid for. As it is said elsewhere in this issue, “we pray for peace, but we pay for war.” When we once understand that, great change will come about. And especially, as war becomes more and more impersonal, with computerized strategic commands and weapons, more people are increasingly going to ask, “Who is waging this war? Are we ourselves responsible, since we pay for it?” (As the old saying goes, “Your checkbook shows where your heart is.”)

Take Richard Catlett, for example, a Friend who — as I write at this very moment in — is beginning his jail sentence of two months at the Kansas City Municipal Rehabilitation Institute (for first offenders) in Kansas City, Missouri. That will be followed by three years of probation. Richard Catlett has been an antiwar activist , refusing to file his income tax return . In , his health food store was closed for non-payment of taxes (it is now under his wife’s ownership), and now, at sixty-nine years of age, Richard Catlett is treated as a criminal.

Clearly, he is being held up as an example of what can happen to a trouble-maker who dares to go against the tax law.… Richard Catlett’s age gives added emphasis to the warning to those no longer young and foolhardy. (Besides, the pockets of those in his age bracket are usually better filled, and not to be overlooked by IRS.)

Catlett’s case was covered in more depth later on in the same issue by means of lengthy quotes from a Colombia Missourian article (see “Local war protester leaves for jail term” in ♇ 5 January 2013) and the following section from a Wall Street Journal article:

Tax Report

A protester got loads of publicity that drew criminal charges for nonfiling.

The IRS selects tax protesters for criminal prosecution based on the amount of publicity they get. Usually protesters who don’t seek the spotlight are pursued by civil actions; criminal is reserved for the publicity hound. Richard Ralston Catlett is a notorious war and tax protester. The sixty-eight-year-old Columbia, Missouri, health food store owner argued that criminal charges of failing to file returns should be dropped because the IRS was guilty of “selective prosecution.”

The government is barred from selecting people to prosecute on grounds of race, religion or the exercise of free speech, or other “impermissible grounds.” Catlett claimed that basing a criminal prosecution on publicity isn’t permitted. But an appeals court disagreed. His exercise of free speech wasn’t involved here, the court noted. The IRS seeks criminal prosecution against publicized protesters to promote compliance with tax laws, the court observed.

“The government is entitled to select those cases for prosecution which it believes will promote compliance,” the court declared.

Next, John K. Stoner wrote a strong, challenging essay inspired by William James’s The Moral Equivalent of War titled “The Moral Equivalent of Disarmament.” Excerpts:

For some decades now we have been hearing the Church call on governments to take steps toward disarmament. And it would be difficult to think of a thing more urgent or more appropriate for churches to say to governments. It is hardly necessary here to give another recitation of the monstrous and unconscionable dimensions of the world arms race, culminating in the ever-growing stockpiles of nuclear weapons and the refinement of systems to deliver their carnage. The Church has done part of its duty when it has said that this is wrong.

But the time has come to say that the good words of the Church have not been, and are not, enough. The risks, the disciplines, the sacrifices, and the steps in good faith which the Church has asked of governments in the task of disarmament must now be asked of the Church in the obligation of war tax resistance. It is, at the root, a simple question of integrity. We are praying for peace and paying for war. Setting euphemisms aside, the billions of dollars conscripted by governments for military spending are war taxes, and Christians are paying these taxes. Our bluff has been called.

In all candor it must be suggested that the storm of objection which arises in the Church at this idea borrows its thunder and lightning from the premiers, the presidents, the ambassadors, and the generals who make their arguments against disarmament. War tax resistance will be called irresponsible, anarchist, unrealistic, suicidal, masochistic, naive, futile, negative and crazy. But when the dust has settled, it will stand as the deceptively simple and painfully obvious Christian response to the world arms race. A score or a hundred other good responses may be added to it. We in the Church may rightly be called upon to do more than this, but we should not be expected to do less.

Let the Church take upon itself the risks of war tax resistance. For church councils to take the position that the arms race is wrong for governments and not to commit themselves and call upon their members to cease and desist from paying for the arms race is patently inconsistent. This is probably a fundamental reason why the Church’s pleas for disarmament have met with so little positive response. Not even governments can have high regard for people who say one thing and do another. If governments today are confronted with the question whether they will continue the arms race, churches are confronted with the question whether they will continue to pay for it. As specialists in the matter of stewardship of the Earth’s resources they have contributed precious little to the most urgent stewardship issue of the twentieth century if they go on paying for the arms race. How much longer can the. Church continue quoting to the government its carefully researched figures on military expenditures and social needs and then, apparently without embarrassment, go on serving up the dollars that fund the berserk priorities? The arms race would fall flat on its face tomorrow if all of the Christians who lament it would stop paying for it.

It is not, of course, simple to stop paying for the arms race as a citizen of the United States, or anywhere else for that matter. If you refuse to pay the portion of your income tax attributable to military spending, the government levies your bank account or wages and extracts the money that way. If your income tax is withheld by your employer, you must devise some means to reduce that withholding, such as claiming a war tax deduction or extra dependents. If, as an employer, you do not withhold an employee’s war taxes, you will find yourself in court, as has recently happened to the Central Committee for Conscientious Objectors. All of these actions are at some point punishable by fines or imprisonment, and none — in the final analysis — actually prevents the government from getting the money. Nevertheless, it must be said that the Church has not tried tax resistance and found it ineffective; it has rather found it difficult and left it untried.

The Church has considered the risk too great. Individuals fear social pressure, business losses, and government reprisals. Congregations, synods, and church agencies equivocate over their role in collecting war taxes. There is the risk of an undesirable response — contributions may drop off, tax-exempt status may be lost, officers may go to jail. To oppose the vast power of the state by a deliberate act of civil disobedience is not a decision to be made lightly (an unnecessary observation, since there are no signs that Christians or the Church in the United States are about to do this lightly).

It would be inaccurate to give the impression that Christians, individually, and the Church, corporately, in the U.S. have done nothing about war tax resistance. There have been notable, even heroic, exceptions to the general manifest lethargy. The war tax resistance case of an individual Quaker was recently appealed on First Amendment grounds to the U.S. Supreme Court, but the court refused to consider it. A North American conference of the Mennonite Church is grappling with the question of its role in withholding war taxes from the wages of employees. Among Brethren, Friends and Mennonites — sometimes called the Historic Peace Churches — there is a rising tide of concern about war taxes. The Catholic Worker Movement and other prophetic voices in various denominations have long advocated war tax resistance, but they have truly been voices crying in the wilderness. For all our concern about the arms race, we in the churches have done very little to resist paying for it. That has seemed too risky.

But then, of course, disarmament also involves risks. Could there be a moral equivalent of disarmament that did not involve risk? In this matter of the world arms race, it is not a question of who can guarantee the desired result, but of who will take the risk for peace.

Let the Church take upon itself the discipline of war tax resistance. Discipline is not a popular word today, but it should be amenable to rehabilitation at least among Christians, who call themselves disciples of Jesus. How quickly does the search for a way turn into the search for an easy way! And how readily do we lay upon others those tasks which require a discipline we are not prepared to accept ourselves!

War tax resistance will involve the discipline of interpreting the Scripture and listening to the Spirit. In a day when the Bible is most noteworthy for the extent to which it is ignored in the Church, it is an anomaly to see the pious rush to Scripture and the joining of ranks behind Romans 13, when the question of tax resistance is raised. In a day when the authority of the Church is disobeyed everywhere with impunity, it is a curiosity to see Christians zealous for the authority of the state. In a day when giving to the Church is the last consideration in family budgeting, and impulse rules over law, it is a shock to observe the fanaticism with which Christians insist that Caesar must be given every cent he wants. As the Church has grown in its discernment of what the Bible teaches about slavery and the role of women, so it must grow in its discernment of what the Bible teaches about the place and authority of governments and the payment of taxes.

War tax resistance means accepting the discipline of submission to the Lordship of Jesus Christ in the nitty-gritty of history. Call it civil disobedience if you wish, but recognize that in reality it is divine obedience. It is a matter of yielding to a higher sovereignty. Those who speak for a global world order to promote justice in today’s world invite nations to yield some of their sovereignty to the higher interests of the whole, and those persons know the obstinacy of nations toward that idea. It may be that the greatest service the Church can do the world today is to raise a clear sign to nation-states that they are not sovereign. War tax resistance might just be a cloud the size of a person’s hand announcing to the nations that the reign of God is coming near. It is clear that Christians will not rise to this challenge without accepting difficult and largely unfamiliar disciplines.

But then, of course, disarmament also involves disciplines. The idea that one nation can take initiatives to limit its war-making capacities is shocking. To do so would represent a radical break with conventional wisdom. How is it possible to do that without first convincing all the nations that it is a good idea?

Let the Church take upon itself the sacrifices of war tax resistance. It is never altogether clear to me whether Christians who oppose war tax resistance find it too easy a course of action, or too difficult. It is said that refusing to send the tax to IRS and allowing it to be collected by a bank levy is too easy — a convenient way of deceiving oneself into thinking that one has done something about the arms race. And it is said that to refuse to pay the tax is too difficult. It is to disobey the government and thereby to bring down upon one’s head the whole wrath of the state, society, family, business associates, and probably God as well. Moreover, the same person will say both things. Which does he or she believe? In most cases, I think, the second.

The sacrifices involved in war tax resistance are fairly obvious. They may be as small as accepting the scorn which is heaped upon one for using the term “war tax” when the government doesn’t identify any tax as a war tax, or as great as serving time in prison. It may be the sacrifice of income or another method of removing oneself from income tax liability. It can be said with some certainty that the sacrifices will increase as the number of war tax resisters increases, because the government will make reprisals against those who challenge its rush to Armageddon. Yet, there is the possibility that the government will get the message and change its spending priorities or provide a legislative alternative for war tax objectors, or both. In any case, for the foreseeable future, war tax resistance will be an action that is taken at some cost to the individual or the Church institution, with no assured compensation except the knowledge that it is the right thing to do.

But then, of course, disarmament also involves sacrifices. The temporary loss of jobs, the fear of weakened defenses, and the scorn of the mighty are not easy hurdles to cross. A moral equivalent will have to involve some sacrifices.

Let the Church take upon itself the action of war tax resistance. The call of Christ is a call to action. It is plain enough that the world cannot afford $400 billion per year for military expenditures, even if this were somehow morally defensible. It is plain enough that the dollars which Christians give to the arms race are not available to do Christ’s work of peace and justice. In these circumstances the first step in a positive direction is to withhold money from the military. If we say that we must wait for this until everybody and (and particularly the government) thinks it is a good idea, then we shall wait forever.

Having withheld the money, the Church must apply it to the works of peace. What this means is not altogether obvious at present, but there is reason to believe that a faithful Church can serve as steward for these resources as wisely as generals and presidents. The dynamic interaction between individual Christians and the Church in its local and ecumenical forms will help to guide the use of resources withheld from the arms race.

This is a call to individual Christians and the Church corporately to make war tax resistance the fundamental expression of their condemnation of the world arms race. Neither the individual nor the corporate body dare hide any longer behind the inaction of the other. The stakes are too high and the choice is too clear for that, though we can have no illusions that this call will be readily embraced nor easily implemented by the Church.

But then, of course, we do not think that disarmament will be an easy step for governments to take either. The Church has an obligation to act upon what it advocates, to deliver a moral equivalent of the disarmament it proposes. If effectiveness is the criterion, it is certainly not obvious that talking about the macro accomplishes more than acting upon the micro. A single action taken is worth more than a hundred merely discussed. (When it comes to heating your home in winter, you will get more help from one friend who saws up a log than from a whole school of mathematicians who calculate the BTUs in a forest.) To talk about a worthy goal is no more laudable than to take the first step toward it, and might be less so.

Michael Miller wrote an article for the same issue that noted that the National Guard is a U.S. military combat function that is largely paid for out of state budgets, not the federal budget. He concluded:

I am now more fully aware how the military affects our daily lives and activities. I also realize that not only is the objection to payment of war taxes a federal issue, but it is also a very real state issue. State budgets contain rather large amounts in this respect.

As Friends, we must be constantly aware of the issues involved with our tax dollars. The military has a great influence over our lives and our tax dollars, whether or not we recognize it. We have a responsibility to make ourselves aware of the issues and how they influence our lives.

Alan Eccleston contributed an article on war tax resistance as a method of testifying for peace — aligning ones life with ones values. This, he felt, could be done in a variety of ways:

We do not have to be prepared for jail to be a war tax resister. We do not have to be ready, at this moment, to subject ourselves to harassment by the Internal Revenue Service. We do, however, have to be truthful on our tax returns. We do have to be clear about our belief in the peace testimony and our desire to align our lives with this belief. And that is all!

If you are clear about that, you can withhold some amount of your tax. It can be a token amount, if that is where you are, say five dollars or fifty dollars. Or it can be the same percent of your tax as the military portion of the current budget, currently thirty-six percent excluding past debt and veterans benefits. (An easy way to do this is to insert the amount under “Credits” as a “Quaker Peace Witness,” line forty-six. Alternately, some people declare an extra deduction, but this is more complicated, since the deduction must be substantially larger than the amount you desire to withhold.) It may bother you that three times or even ten times what you have chosen to withhold is going to be spent for war preparations. But far better to take this small step than to turn away from the witness. Write your congresspersons and tell them of your concern. Urge them to pass the World Peace Tax Fund which would acknowledge your constitutional right to practice your religious beliefs without harassment and penalty.

Alternatively, if the government owes you money fill out the (very short) Form #843 “Request for Refund,” asking that they refund the amount you wish for peace witness.

One can also anticipate the withholding problem by filling out a W-4 Form at your place of employment declaring (truthfully) an allowance for expected deductions that includes the amount of your peace witness.

Then what? You can expect a series of computer notices stating that you calculated your tax incorrectly and you owe the amount shown on the notice. This may also include an addition of seven percent annual interest on the amount owed. (Currently IRS seems not to be adding on penalty charges but that is a possibility.)

You have a choice: you can ignore the notice; you can write or call IRS and discuss it; or you can pay the tax. Sooner or later you will receive a printout that says “Final Notice.” If you again fail to pay the amount owed, you will probably receive a call from someone at IRS who will try to convince you that the whole process has gone far enough and that your purpose is better served by paying the government. IRS wants to collect. That is their job; when they have done it, they are through with you. They cannot, by law, be harsh or punitive. There is no debtors’ prison in this country. If you declare the intent of your witness on your tax form and by letter to Congress, you cannot be convicted of fraud; therefore, you are not risking criminal penalties.

In other words, the tax resister controls the process. One can witness to peace so long as it can be done lovingly and, if it is to be a meaningful witness of peace, that is the only way it can be done.

However, if one’s family obligations or other matters are too pressing, or if one’s spiritual resources are being unduly strained, it is time to lay down this particular witness. One can carry on the witness and still bring the process to a conclusion by letting the payment be taken from a bank account or peace escrow fund. Another round of letters to Congress and the president will testify to your continuing concern even after the pressure of collection has been relieved.

In your witness, no matter how small the amount withheld or how short the duration, you will gain strength and courage and insight. This brings new resources to your next witness. It gives you knowledge and resources to share with others, which in turn helps their witness. In sharing, you both are strengthened. Thus, a personal witness becomes a “community of witness,” and the “community of witness” gains strength, courage, and insight in its mutual sharing. This witness and this sharing of Christian love becomes its own witness to the testimony of peace — the testimony of love for God, for ourselves, for humankind.

(A letter from Dorothy Ann Ware in a later issue credited the Eccleston article for spurring her to “make a token Quaker Peace Witness by withholding a very small portion of my income tax. So Step One has been taken…”)

The same issue reprinted a Minute from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting which encouraged Quakers “to give prayerful consideration… to the option of refusal of taxes for military purposes.” Furthermore:

We reaffirm the Minute of the yearly meeting which states in part that “…Refusal to pay the military portion of taxes is an honorable testimony, fully in keeping with the history and practices of Friends… We warmly approve of people following their conscience, and openly approve civil disobedience in this matter under Divine compulsion. We ask all to consider carefully the implications of paying taxes that relate to war-making… Specifically, we offer encouragement and support to people caught up in the problem of seizure, and of payment against their will.”

We request the Representative Meeting to arrange for the guidance of meetings and their members on the form of military tax resistance suitable for individuals in accordance with that degree of risk appropriate to individual circumstances, for advice on consequences, and for consideration of legal and support facilities that may be organized.

We also request Representative Meeting to provide for an Alternate Fund for sufferings, set up under the yearly meeting to receive tax payments refused, for those tax refusers who may wish to utilize this fund.

We recommend cooperation with the Historic Peace Churches and other religious groups in further consideration of non-payment on religious grounds of military taxes.

Following that, John E. Runnings wrote of his and his wife Louise’s war tax resistance, and decried the injustice of a “society that requires that Quakers, who renounce war and recognize no enemies, must pay as large a contribution to the support of the war machine as those who fully accept the malicious nature of other nationals and who are so frightened of their ill intent that no amount of extermination equipment is enough to assure security.”

The social reforms that we credit to George Fox’s influence did not come about by his waiting on the Spirit but rather by his responding to the Spirit. If just one man could accomplish so much by responding to the Spirit, what would happen if several thousand modern Quakers were to respond to their spiritually-inspired revulsion to assisting in the building of the war machine?

If Quakers could be induced to discard their excuses for their financial support of the arms race and to withhold their Federal taxes, who knows how many thousands of like-minded people might be encouraged to follow suit? And who knows but what this might bring a halt to the mad race to oblivion?

There was a brief update about Robert Anthony’s case. Anthony hoped to use his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination (presumably in response to a government request for financial records or something of the sort). The judge in the case asked if the government would grant Anthony immunity from prosecution for anything he disclosed, which would have cut off the Fifth Amendment avenue of resistance, but the government wasn’t prepared to do that, and that’s where the matter stood.

The issue included a notice that the Center on Law and Pacifism had “recently published a military tax refusal guide for radical religious pacifists entitled ‘People Pay for Peace’ ” but also noted that “the Center states that it is in ‘urgent and immediate need of operating funds.’ ”

A later issue gave some more information about the Center:

The Center was started after a former Washington constitutional lawyer and theologian, Bill Durland, met a handful of conscientious objectors who were appealing to the U.S. courts for their constitutional rights to deny income tax payments for the military.…

That was in . The Center is now producing regular newsletters and has published a handbook on military tax refusal. It has organized war-tax workshops for pacifists representing constituencies in the Northeast, South and Midwest. One of its projects was the “People Pay for Peace” scheme, under which it was suggested that each individual deduct $2.40 from his/her income tax return to “spend for peace”: that sum being the per capita equivalent of the $193,000,000,000 which will be consumed in for war preparation in the United States. This was a protest action against the fifty-three percent of the U.S. budget allocated to military purposes.

The Center on Law and Pacifism is a “do-it-yourself cooperative” which relies on both volunteer professional assistance and individual contributions.

Hmmm… my calculation for 53% of the federal budget in 1979 is more like $214,618,730,000… and per-capita (by U.S. population, anyway) that would be $953.63 per person. If you use the $193 billion value, that’s still $857.57 per person. Even if you use world population, you still get $44.08–$49.02 each. Somebody’s confused… maybe it’s me.

Wendal Bull penned a letter-to-the-editor in the same issue about his experience as a war tax resister twenty years before. Excerpt:

In I received a lump sum payment of an overdue debt. This increased my income, which I normally keep below the taxable level, to a point quite some above that level. I distributed the unexpected income to various anti-war organizations. I anticipated pressure from IRS officers, so in the autumn, long before the tax would be due, I disposed of all my attachable properties. This action, under the circumstances, I believe to be unlawful. But it seemed to me a mere technicality, far outweighed by the sin of paying for war, or the sin of permitting collection of the tax for that purpose. After disposing of all attachable properties, I wrote to IRS telling them I had taxable income in that year but chose not to calculate the amount of it because I had no intention of paying it. In the same letter I explained my reasons for conscientious non-cooperation with Uncle Sam’s preparations for war in the name of “defense.”

My letter appeared in full or in generous excerpts in at least three daily papers and several other publications and I mailed copies to friends who might be interested. I am not a publicity hound nor a notorious war resister. The publicity did seem to effect a fairly prompt visit from the Revenue Boys. They paid me three or four visits. On one occasion two men came; one talked, the other may have had a concealed tape recorder, or was merely to witness and confirm the conversation. After quizzing me for an hour or more they left courteously, whereupon I said I was sorry to be a bother to them. At that the talker said, “You’re no trouble at all. I brought a warrant for your arrest, but I’m not going to serve it. It’s the guys who hire lawyers to fight us that give us trouble.” If they had caught me in a lie, or giving inconsistent answers to their probing questions, I suspect the summons would have been served. I was fully prepared to go to court and to be declared guilty of contempt for not producing records to show the sources of my income. I had told the men I was in contempt of the entire war machine and all officers of the legal machinery who aimed to penalize citizens for non-cooperation with war preparations.

Later came two visits from a man who attempted to assess my income for that year, and the law required him to try to get my signature to his assessment. I considered that a ridiculous waste of taxpayer’s money. The man agreed with a smile. Still later, there came several bills, one at a time, for the amount of the official assessment, plus interest, plus delinquency fee, plus warnings that the bill should be paid. These I ignored, of course. The head men knew I would not pay; and they knew they had not any intention of trying to force collection.

I have no idea who decided to quit sending me more bills. I think the claim is still valid since the statute of limitations does not apply to federal taxes.

It is inconvenient to have no checking account, to own no real estate, to drive an old jalopy not worth attaching, and so on. Some of us choose this alternative rather than to let the money be collected by distraint.

In the same issue, Keith Tingle shared his letter to the IRS, which he sent along with his tax return and a payment that was 33% short. He stressed that he didn’t mind paying taxes — “a small price for the tremendous privilege of living in the United States with its heritage of freedom, equal protection, and toleration” — but that “I do not wish my labor and my money to finance either war or military preparedness.”

Stephen M. Gulick also wrote in. “Because the military and the corporations need our money more than our bodies, war tax resistance becomes important — in all its forms from outright and total resistance to living on an income below the taxable level,” he wrote. “Fundamentally, war tax resistance must lead us to look not only at warmaking and the preparation for war, but also at the economic, social, and political practices that, with the help of our money, nurture the roots of war.”

Colin Bell attended the Southern Appalachian Yearly Meeting:

“I think,” Colin said, “that as a Society we are standing at another moment like that, when our forebears took an absolutely unequivocal stance” and we don’t know what to do. Are we looking for something easy, he wondered, suggesting that it probably should be tax resistance. Accepting the title Historic Peace Church, he declared, makes it sound like a worthy option, rather than it being at the entire heart and core of Christendom.

A letter to the editor of the Peacemaker magazine from John Schuchardt is quoted in the issue:

I have recently received threatening letters from a terrorist group which asks that I contribute money for construction of dangerous weapons. This group makes certain claims which in the past led me to send thousands of dollars to pay for its militaristic programs. The group claimed: 1) It was concerned with peace and freedom; 2) It would provide protection for me and my family; 3) It was my duty to make these payments; and 4) I was free from personal responsibility for how this money was spent in individual cases.

Last year, for the first time, I realized that these claims were fraudulent and I refused to make further payments…

That issue also noted that the Albany, New York, Meeting “joined the growing number of meetings which are calling on their members to ‘seriously consider’ war tax resistance…” That Meeting was also considering establishing its own alternative fund, and was hoping Congress would pass the World Peace Tax Fund bill.

This “seriously consider” language, along with the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting’s earlier-mentioned call for Quakers “to give prayerful consideration” to war tax resistance, is a far cry from the sort of bold leadership John K. Stoner was calling for. But then again, Quaker Meetings were no longer the sorts of institutions to bandy about Books of Discipline and threaten “disorderly walkers” with disownment, or even to give them “tender dealing and advice in order to their convincement.” Meetings had in general become much more humble about what sort of direction they should provide and what sort of obedience they could expect. It is hard to imagine a Meeting from this period adopting a commandment along the lines of the Ohio Yearly Meeting’s discipline — “a tax levied for the purchasing of drums, colors, or for other warlike uses, cannot be paid consistently with our Christian testimony.”

The issue included a review of Donald Kaufman’s The Tax Dilemma: Praying For Peace, Paying for War, a book that defends war tax resistance from a Christian and Biblical perspective. “What is the individual’s responsibility in the face of biblical teachings and the history of tax resistance since the early Christian centuries? Some biblical passages have been used to justify the payment of any and all taxes. But Kaufman warns us to consider these passages in their historical context and in the light of the primary New Testament message: love for God, oneself, one’s neighbor, and one’s enemy.”

That issue also included an obituary notice for Ashton Bryan Jones that noted “[h]is courage in the face of the harsh treatment that he endured in the struggle for social justice and against war taxes…”

The issue reported on the New England Yearly Meeting, which held a workshop on war tax resistance, and also agreed to establish a “New England Yearly Meeting Peace Tax Fund.”

Recognizing that each of us must find our own way in this matter, the new fund is seen not as a general call to Friends to resist paying war taxes but specifically to help and to hold in the Light those Friends who are moved to do so. The fund will be administered by the Committee on Sufferings, which came into being last year to support Friends who are devoting a major portion of their time and energies to work for peace.

New Call to Peacemaking

The “New Call to Peacemaking” brought together representatives of the Mennonites, Brethren, and Quakers in , and to try to strengthen their respective churches’ anti-war stands. It continued to ripple through the pages of the Journal in . Barbara Reynolds covered the Green Lake conference that drafted the New Call statement in the issue. Among her observations:

In my own small group, I saw social action Friends struggling with Biblical language and coming to accept many scriptural passages as valid expressions of their own convictions. And I saw a respected Mennonite, a longtime exponent of total Biblical nonresistance, courageously re-examining his position and corning out strongly in favor of a group statement encouraging non-payment of war taxes.

Elaine J. Crauder gave another report on the project in the issue. Excerpts:

Quakers, Mennonites and Brethren are known as the Historic Peace Churches. How do they witness against evil and do good? Where does God fit into their witnessing? Are they responding to the urgency of the present-day world situation, or are they truly “historic” peace churches, with no relevance to today’s complex world?

The New Call to Peacemaking (NCP) developed out of exactly these concerns: Where is the relevance and what is the source of our witnessing? The answers were clear. To seek God’s truth and to witness, in a loving way, by doing good (through peace education, cooperation in personal and professional relationships, living simply and investing only in clearly life-enhancing endeavors) and by resisting evil (working for disarmament and peace conversion, resisting war taxes and military conscription).

Crauder says she first started thinking about her support of war through her taxes in :

The 1040 Income Tax form didn’t have a space for war tax resisters. Either I would have to lie about having dependents, or my taxes would be withheld. l didn’t feel that I had a choice. It did not occur to me to claim a dependent and then support that person with the funds that thus wouldn’t go for war. So, I did what was easiest — nothing — and paid my war taxes.

In , she says:

I started to think about my taxes again. Maybe I could lie on my form. It was definitely not right to work for peace and pay for the war machine. I even went to one meeting of the war tax concerns committee. But there were enough meetings that I had to go to, so I managed not to find the time to struggle with my war taxes. Words of John Woolman seemed to fit my condition:

They had little or no share in civil government, and many of them declared they were through the power of God separated from the spirit in which wars were; and being afflicted by the rulers on account of their testimony, there was less likelihood of uniting in spirit with them in things inconsistent with the purity of Truth.

Woolman was referring to the early Quakers when he said it was less likely that they would be influenced by the civil government in questions of the truth. It seemed to me that in Woolman’s time it was also easier to be clear about the truth — we are so much more dependent and tied to the government than they were. Perhaps it is always easier to have a clear witness in hindsight.

I think Crauder has it a little backwards here. Woolman was speaking of early Friends in England, who were being actively repressed by the government and banned from much of any exercise of political power, and contrasting them to the Quakers in Woolman’s own time and place (colonial Pennsylvania), where Quakers held political power, and were by far the dominant party in the colonial Assembly. In Woolman’s time the government and the Society of Friends were as tightly linked as they ever have been.

Historical notes

In the issue, Walter Ludwig shared an interesting anecdote about Susan B. Anthony’s father, Daniel Anthony:

During the Mexican War he made the quasi tax-resisting gesture of tossing his purse on the table when the collector appeared, remarking, “I shall not voluntarily pay these taxes; if thee wants to rifle my pocketbook thee can do so.”

I hunted around for a source for this anecdote, and found one in Ida Husted Harper’s The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony (1898), where she put it this way:

In early life he had steadfastly refused to pay the United States taxes because he would not give tribute to a government which believed in war. When the collector came he would lay down his purse, saying, “I shall not voluntarily pay these taxes; if thee wants to rifle my pocket-book, thee can do so.” But he lived to do all in his power to support the Union in its struggle for the abolition of slavery and, although too old to go to the front himself, his two sons enlisted at the very beginning of the war.

John Woolman was invoked in the issue as someone who “took as clear a stand on payment of taxes for military ends as he did on slavery.” He was quoted as saying:

I all along believed that there were some upright-hearted men who paid such taxes but could not see that their example was a sufficient reason for me to do so, while I believed that the spirit of Truth required of me as an individual to suffer patiently the distress of goods rather than pay actively.

Bruce & Ruth Graves

The issue brought an update on the case of Bruce and Ruth Graves, who were pursuing a Supreme Court appeal in the hopes of legally validating their approach of claiming a “war tax credit” on their federal income tax returns. They were trying to get people to write letters to the Supreme Court justices, in the hopes that they would find influential the opinions of laymen on such points as these:

1) petitioners right to First Amendment free exercise of religion and freedom of expression, 2) paramount interests of government not endangered by refusal of petitioners to pay tax, 3) petitioners should be able to re-channel war taxes into peace taxes (via World Peace Tax Fund Act, etc.), 4) IRS regulations should not take precedence over Constitutional rights of individuals, 5) threat of nuclear war must be stopped by exercise of Constitutional rights, 6) other pertinent points at the option of correspondent.

There was a further note on that case in the issue — largely a plea for support, without any otherwise significant news. Included with this was a message from the Graveses with this plea: “How can Friends maintain the secular impact of the peace testimony expressed through conscientious objection when technology has replaced the soldier’s body with a war machine? Does it not follow that technology then shifts the emphasis of conscientious objection toward reduction of armaments by resisting payment of war taxes?”

The issue brought the news that the Supreme Court had turned down the Graveses’ appeal. “[W]hen asked whether the frustrations of losing the long court battle had ‘generated any thoughts of quitting,’ Ruth Graves replied, ‘Never. If I were going to let myself be stopped by seemingly hopeless causes, I’d just die right now.”

World Peace Tax Fund

A note in the issue reported that some people who had “sent in cards or letters expressing support for the [World Peace Tax Fund] bill” had reported that they had “been subjected to IRS audits and other harassment.”

A letter from Judith F. Monroe in the issue expressed some concern about the World Peace Tax Fund plan. Excerpts:

I fear the World Peace Tax could become a device to appease the consciences of those of us who are not willing to face the consequences of civil disobedience.…

…One important purpose of the tax is to shake the complacent into a realization of the madness of our current armaments race. I don’t believe the casual matter of checking a block on a tax form will ever cause extensive introspection on the part of most people.

How will peace tax funds be handled? Will such a tax require more complex tax laws, IRS investigators, and tax accountants? How can we believe in the government’s ability to use such funds constructively? I can envision the Department of Defense receiving peace grants. After all, they’re the boys who fight for peace. This may be an exaggeration. The point is I do not feel we can trust any large bureaucracy with the task of peacemaking.

If the majority or at least a sizable minority do not opt for the peace tax, all that will happen is a larger percentage of their taxes will go to armaments to compensate for the monies diverted by the few who chose a peace tax. Under such circumstances, the peace tax would accomplish little.

Evidence of some critical appraisal of the “peace tax” idea is also found in a note in the issue, which summarizes an address by Stanley Keeble to the June General Meeting in Glasgow, Scotland:

If this were permitted, would not government simply raise military estimates to compensate for expected shortfall? Would not people not conscientiously opposed to military “defense,” take advantage of such legislation? Would the procedure be destructive of democracy and majority rule? Should not individuals rather reduce their earnings to a non-taxable level, or would that deprive useful projects of legitimate funds? Other such questions were raised, relating to possible effects on national “defense” policy. For his part, however, Stanley Keeble felt that it was important to “bring a peace decision right to the level of the individual,” and added that of fifteen replies so far received from monthly meetings on the subject of a Peace Tax Fund, only one was completely negative, two uncertain, and “the rest endorsed the proposal whilst acknowledging certain difficulties.”

There were occasional reports on the bill’s status in Congress scattered through the issues of the Journal. One, in the issue, said:

Endorsed by the national bodies of the Unitarian-Universalist Association, the United Methodist Church, the United Church of Christ, the Roman Catholic Church, the Church of the Brethren, the Mennonites, and the Religious Society of Friends, this bill provides the legal alternative for taxpayers morally opposed to war that the military portion of their taxes would go into the WPTF to be used for a national peace academy, retraining of workers displaced from military production, disarmament efforts, international exchanges and other peace-related purposes; alternatively for non-military government programs.

That issue also quoted the newsletter of the Canadian Friends Service Committee on the legislation, saying: “Thousands of letters and postcards were sent to members and many meetings held across the country as well as slide-tape shows, television and radio programs. Newspaper coverage was also good. The U.S. government is beginning to act in response.”

This is the tenth in a series of posts about war tax resistance as it was reported in back issues of The Mennonite. Today we finish off the 1950s.

In general, except for a brief flurry of mostly noncommittal articles in the late 1940s, The Mennonite seemed to steer clear of the topic of war tax resistance thereafter, with a few exceptions.

In the issue, Lloyd L. Ramseyer wrote of “The Sin of Just Being Good” — that is of “people who are content to just be good without concerning themselves very much with the evil about them.” One way this might display itself?

Do we sometimes shift the responsibility to others, saying this is no business of mine? May it be that we sometimes even employ others to do what we think it is wrong for us to do ourselves, and then seem to feel that it is not our affair?… If three-fourths of my tax dollar goes for war, can I have a conscience clear of it?

An article on “Taxes” in the issue gave some very middle-of-the-road advice:

In the classic passage, Matthew 22:17–22, Jesus states that He expected His followers to pay taxes.

“Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.”

Very briefly, we want to say four things:

- Christians ought to be honest in filing tax returns…

- Christians should not pay too much tax…

- Christians ought to take advantage of deductions and through contributions…

- Christians ought to study best ways to give as to tax…

There was not even a hint of a suggestion that a Christian ought to be concerned about what use Caesar puts the tax to, or might have to draw a line somewhere and refuse. The “Render Unto Caesar” episode is portrayed as though when Jesus was asked whether Jews ought to pay taxes to Caesar or not, he had simply replied “yes” but in a more wordy way than necessary. (“When they heard this, they marvelled…” perhaps this is just a mistranslation for “they yawned and checked their wristwatches.”)

The issue also had an article on the income tax that uses a different verse to also counsel tax obedience:

The time of year has come again when the citizens of our country will have to pay income tax. The question is sometimes raised, should Christians pay this tax? A large percentage of the income tax money goes for war purposes. A Christian obeying the new commandment of Jesus to love his neighbor as himself cannot possibly be in accord with hatred, strife, and bloodshed resulting from war. What then shall we do about it? Refuse to pay and come in conflict with the laws of our country?

Jesus our Lord has given us a very clear teaching on this subject in Matthew 17:24–27. The collector of the tribute money asked Peter if Jesus paid tribute. Peter answered, “yes.” Jesus preventing Peter from telling him the incident, asks Peter “of whom do the kings of the earth take custom or tribute? of their own children, or of strangers?” Peter said of strangers. Jesus answered, “then are the children free. Notwithstanding, lest we offend them, go to the sea, cast a hook, and take the first fish thou catchest, open his mouth and take out the coin therein and give it to the tribute collector.”

The Roman tribute money was used mostly for military purposes. The Roman Empire was then ruling the major part of the then known world. It required large armies to subdue and occupy these many nations. The money consumed for military purposes was a large sum. Jesus asked Peter to pay for both of them.

Tax was again the subject of an article in the issue, but this time the message is much changed:

Taxes

Daniel Graber

Pastor, Silver Street Church, Goshen, Ind.Dear Quiet of the Land;

PAX… VOLUNTARY SERVICE… 1‒W… What does it all mean? Yes, it means a positive witness for peace; but in a vision the other night I heard 1000 angels shouting, “Awake! Awake! Ye Quiet of the Land!”

And then the angel Gabriel went on to explain: “Ah, yes, you Mennonites are righteous, peace-loving, law-abiding citizens of your land; but what are you doing at this time so near the death of your Lord? Does not your Christian conscience move you at more points than that of nonresistance to war and your interest in finding a peaceful alternative?

“You who proclaim to the world that you are Christ’s disciples would now also deny thy Lord! Ah, yes, my Lord did boldly say, ‘Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s’; but are you living under the Roman Empire where you have no political freedom? No, you are citizens in a free republic, a land founded with an appreciation for your conscience. Did you not hear the words of John Milton: ‘The passage “render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s” does not say “Give Caesar thy conscience.”’

“You, the Quiet of the Land, are ordering a huge portion of that which crucifies your Lord when you pay your federal taxes. Did you know, fine Mennonites, that you are ordering H-Bombs which will destroy cities of a million men, women, and children?… Did you know you are ordering massive retaliation which will destroy most of mankind and cause more mass suffering than our world has ever known?… Did you know you are ordering nuclear bomb tests which poison the atmosphere for a hundred generations yet unborn?… Did you know you are ordering the top secret horror weapon, by paying in advance for it, to be delivered any day now?”

As Gabriel finished, the chorus of angels replied from the background; “No! Gabriel, No! Most Mennonites did not order these horrible weapons. They were ordered for them unawares — yet we must admit they did give silent consent. Most of them didn’t realize that Washington sent all of them a bill for these macabre instruments of suicide and moral degradation in the name of democracy.”

That bill for the coming year amounts to $43,300,000,000 for Defense, or 60 per cent of the total estimated expenditures of the national government. Over half of the total budget is raised from individual income taxes, Mennonites included.

In 20 per cent of the budget went to the War and Navy Departments to defray the cost of national security. In this item went down to 14 per cent of the budget. Possibly these figures do not mean very much now, but taken in comparison to the present amount, it is ten times less than the 43 billion dollars now at our doorstep.

At what point, my dear friends, does one cease to add a pinch of incense and begin to engage in idolatrous worship, and thus deny our Lord? The cost of the Federal Government operation in the budget was $55 per person, even then more than what many people gave to the church. The budget will cost about $455 per person. If you wish to put this into the Mennonite picture, here is an up-to-date report.

In Elkhart County, Indiana, where the population is 84,512 ( Census), there are over 8,800 Amish and Mennonites (Mennonite Encyclopedia). Elkhart County will pay $43,642,912 as their share of the cost of federal government spending. It is assumed that Mennonites of Elkhart County will pay at least their share, which amounts to more than 10.4 per cent, or $4,538,862 plus.

If we could believe that even 40 per cent of the budget would be legitimately used for democracy, it means that the Mennonites of Elkhart County alone are putting into preparation for future wars close to three million dollars a year. That amount of money would be sufficient to operate the entire MCC program for more than a year, or to build several new Mennonite Biblical Seminaries, or a number of hospitals, old people’s homes, colleges, high schools, etc.

From the soldiers of the cross we hear these testimonies concerning taxes. John Woolman, who refused payment in : “To refuse active payment at such a time might be construed to be an act of disloyalty, and appeared likely to displease the rulers, not only here but in England; still there was a scruple so fixed on the minds of many Friends that nothing moved it.”

Bishop Andrew Ziegler, a Mennonite, in the Revolutionary War period; “I would as soon go to war as to pay the three pounds and ten shillings.”

A.J. Muste (Secretary Emeritus of the Fellowship of Reconciliation): “The two decisive powers of government with respect to war are the power to conscript and the power to tax. In regard to the second I have come to the conviction that I am at least conscience bound to challenge the right of the government to tax me for waging war, and in particular for the production of atomic and bacterial weapons.”

Ernest and Marion Bromley (Sharonville, Ohio): “We regard it as the prerogative of every individual to refuse to aid this government or any other government either to prepare for or to engage in war. The time has come when men ought no longer to depend solely upon their spoken witness against war. They ought to prepare themselves for outright resistance by a thorough-going dissociation with the war-making system. No testimony for peace can afford to become a timid shadow. No matter what one may say against our armaments, if he is still paying for armaments, it seems to be talking peace and preparing for war.”

“Awake! Awake! Ye Quiet of the Land!” Think before you begin paying Defense dollars. Convert them to Peace and the Church today.

―From The Christian Evangel.

(slightly condensed)

An article on “Christians and Bomb Tests” in the issue touched on war tax resistance briefly:

Christians have responded to the challenge of this issue in various ways. A few have refused to pay the proportion of their tax that is used for military purposes. Some have voluntarily limited their income to the low level that is tax-exempt…

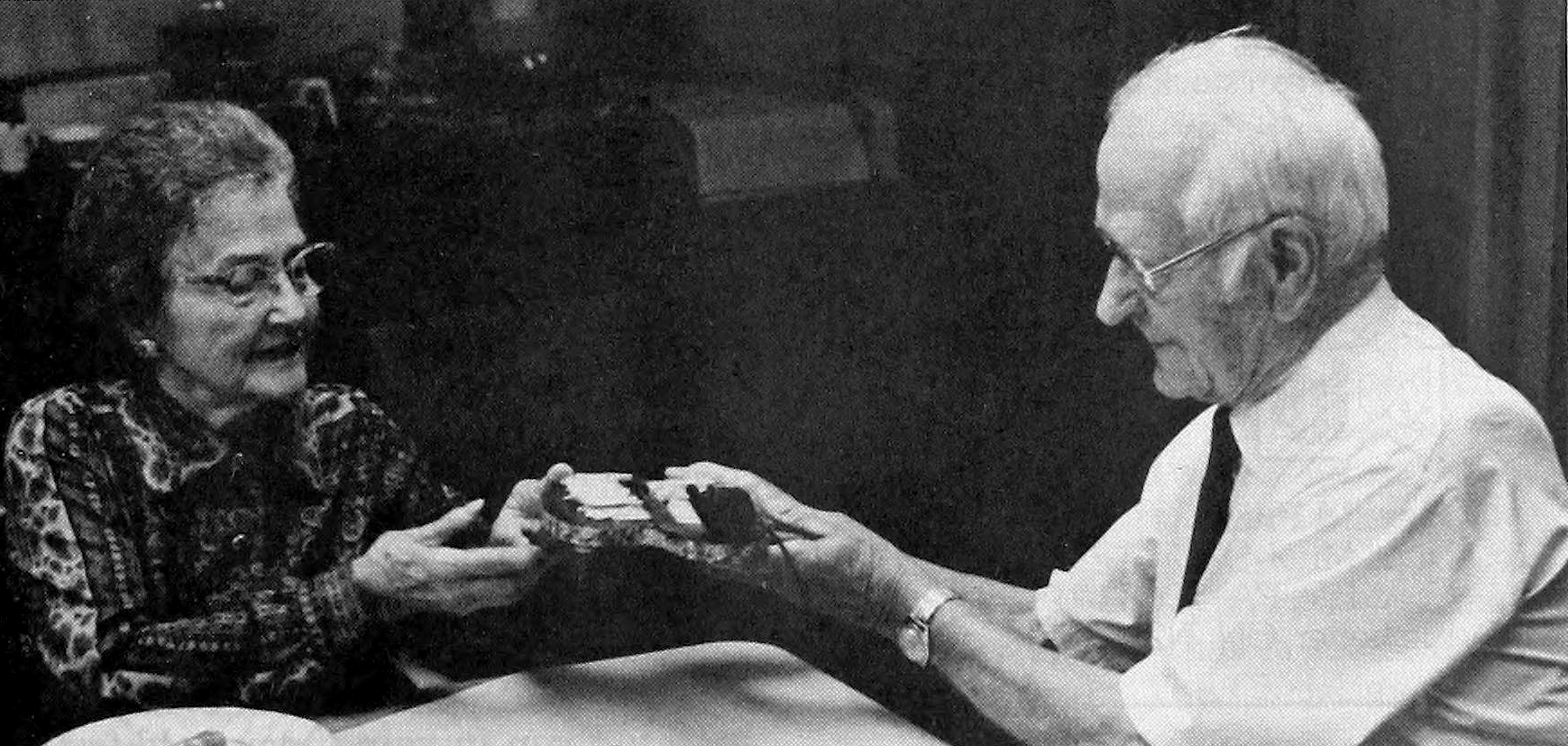

The issue included Don and Eleanor Kaufman’s letter to the IRS:

Can Christians Pay for War?

As Mennonite Christians filed their income tax returns for , more than one was disquieted to realize that tithing Christians were not giving nearly as much to further God’s kingdom as they were paying for military preparation for war! Two Mennonites decided to give voice to this concern in the following letter.

U.S. Treasury Department

Internal Revenue Service

Washington 25, D.C.Gentlemen:

In filing income tax returns for we believe it is necessary to clarify our concerns. Like others who have been perplexed by the irresponsible use of tax money for military purposes, we are earnestly seeking for a constructive way in which to be honest with what we understand about the issue. Personally, we are unable to acquiesce easily to the present military expenditures of our government which we believe, are irrelevant to the problem they are trying to solve. One cannot change ideologies or correct evil by destroying those in whom these forces reside.

In an effort to reduce our cooperation in a warmaking system to a minimum, we seriously considered refusing payment of that portion used for military expenditures (which we understand is about 73 per cent of federal taxes). Since we object on religious grounds to participation in war and military preparation in any form, we believe, like Milton Mayer, that we are denied the free exercise of our religion (guaranteed by the First Amendment to the Constitution) when forced to pay income taxes used for military purposes.

If money represents a part of a person’s life, as we believe it does, then it logically follows that a Christian will have ambivalent feelings about professing peace and good will while at the same time supporting explicitly destructive forces within a government. As there are provisions for conscientious objection to military service, there should also be provisions for conscientious objection to making H-bombs or paying for the making of them.

Consequently, in the interests of our government and all people, we are looking for some alternative whereby it would be possible to channel that portion of tax money to those causes which contribute to the welfare of people — those legitimate functions which are constructive and not destructive of human value.

We hope that the United States government will accept our offer to pay the equivalent or more of the military tax to some mutually agreeable agency, organization, or institution, like CROP, MCC, Church World Service, or the United Nations (UNESCO, Technical and Economic Assistance Program, etc.), which is committed to a peaceful program for all men. We feel that a voluntary arrangement something like Edith Green’s bill H.R. 12310 is necessary if we are to make possible the conditions of a lasting and abiding peace.

(This was the earliest of the “peace tax fund” legislative proposals. It set up a fund to be used to give aid developing nations, and would have allowed taxpayers to get up to a 2% deduction on their taxes by donating to the fund.)

As Christians, we are not seeking exemption from the payment of taxes, but we are searching for a right to determine how those taxes are used, especially those which we contribute personally. It is clear to us that a Christian has a responsibility to government, significantly because in a democracy he is a real part of the government. Because the Christian knows something of the value and importance of community he will do everything he can to contribute to the stability and welfare of government on all levels.

Yet if this person realizes the destructive character and devastating results of all military preparation, he will consider it his patriotic duty to do what he can to avoid collective disaster. We believe responsible citizenship implies that there is no blanket endorsement for what a government does. Its actions must be tested and if they are found to be outside of the purpose of God they are to be challenged.

We hope you will feel with us the urgent need to recognize the priority which God always deserves in every human decision. We would appreciate your thoughtful response to this crucial issue.

Don and Eleanor Kaufman

Moundridge, Kansas

The issue reported as follows:

War Tax Concern

Akron– Concern for payment of war taxes has been expressed by the General Brotherhood Board of the Church of the Brethren. Board Executive Secretary W. Howard Row writes, “The concern is real and the problems to implement (an alternative to payment of war taxes) are great. However, probably no greater than that of securing an alternative to military service.” In a resolution shared with MCC and similar organizations the General Brotherhood Board states: Because there is a growing interest among Brethren and others in finding a positive alternative to the payment of that portion of federal income taxes that go for war preparations, the General Brotherhood Board voted that explorations be made with the appropriate agencies of government to the end that an acceptable constructive alternative be provided for all those persons who, by reason of religious training and belief, conscientiously object to the payment of that portion of income taxes going for military defense. These explorations might be made in concert with one or the more of the other organizations with which we are associated or if necessary by Brethren alone.”

A similar reaction was recently expressed by two Mennonites. Mr. and Mrs. Don Kaufman (Moundridge, Kan.) who are under appointment as MCC workers in Indonesia [and who] assert in a letter to the U.S. Treasury Department: [quote from above letter omitted]

On the MCC Executive Committee met, and, according to a later article on the meeting, “[r]eferred to Peace Section the invitation from the Church of the Brethren to study whether there might be a positive alternative provided by the U.S. government for persons conscientiously opposed to paying that portion of income taxes going for military defense.”

The Mennonite Central Committee annual report for included a report from this “Peace Section.” They noted that “throughout our constituency… [c]oncern is evident in discussions about possible participation in various protest actions and about the propriety of paying income taxes that are used so largely for war purposes…”

Our next episode will pick up as the tumultuous 1960s begin.

This is the thirteenth in a series of posts about war tax resistance as it was reported in back issues of The Mennonite. Today we continue our trek into the 1960s.

The issue included an article by Leo Driedger titled “The Taxes that Go to War”. We met Driedger in our last episode as he was answering a query about the General Conference Mennonite Church’s guidance regarding war taxes on behalf of the Peace and Social Concerns Committee.

In this new article, Driedger begins by methodically explaining how much of the federal budget is military spending, and how the government gets that money to spend. Then he explores the options for avoiding complicity:

Some think we should work out some alternative to paying taxes. In the past some Mennonites paid for other people to go to war in their place. We thought this was wrong so we sought alternative service. But we are still paying for war with our taxes. In order to discuss our taxes intelligently we need to know where we are paying taxes, and how it is spent.