This may seem a little out-there, but I’d like you to consider radical honesty as a tactic with potential to augment a tax resistance campaign.

Radical honesty at its most extreme means abjuring subterfuge — conducting your campaign in the open, in plain sight, without trying to take your opponent by surprise through trickery, and without trying to influence people by “spin” and lopsided propaganda. But it also means studiously refusing to participate in the dishonesty by which your opponent holds on to power and deceives those who give in to it.

Radical honesty has several potential advantages:

- It provides a stark moral contrast between your campaign and whatever institution you are opposing.

In The Story of Bardoli, Mahadev Desai described how this played out in the Bardoli tax strike:

This contrast can make your campaign more appealing to potential resisters and to by-standers, and can increase the morale of the resisters in your campaign.…a regular propaganda of mendacity was resorted to [by the Government]. The Government’s way and the people’s way presented a striking study in contrasts. On one side there were secrecy, underhand dealings, falsehood, even sharp practice; on the other there were straight and manly speech, and straight action in broad daylight.

- Tyranny thrives on mutual dishonesty, and honesty threatens it.

The way people signal their loyalty to the tyrant is to participate in the lie. When everybody around you is participating in the lie, it feels like everyone is loyal to the tyrant. Vaclav Havel wrote of this:

But people may start to refuse:Individuals need not believe all these mystifications, but they must behave as though they did, or they must at least tolerate them in silence, or get along well with those who work with them. For this reason, however, they must live within a lie. They need not accept the lie. It is enough for them to have accepted their life with it and in it. For by this very fact, individuals confirm the system, fulfill the system, make the system, are the system.

Tolstoy went even further, and claimed that radical honesty was itself enough to topple governments:Living within the lie can constitute the system only if it is universal. The principle must embrace and permeate everything. There are no terms whatsoever on which it can co-exist with living within the truth, and therefore everyone who steps out of line denies it in principle and threatens it in its entirety.

No feats of heroism are needed to achieve the greatest and most important changes in the existence of humanity; neither the armament of millions of soldiers, nor the construction of new roads and machines, nor the arrangement of exhibitions, nor the organization of workmen’s unions, nor revolutions, not barricades, nor explosions, nor the perfection of aërial navigation; but a change in public opinion.

And to accomplish this change no exertions of the mind are needed, nor the refutation of anything in existence, nor the invention of any extraordinary novelty; it is only needful that we should not succumb to the erroneous, already defunct, public opinion of the past, which governments have induced artificially; it is only needful that each individual should say what he really feels or thinks, or at least that he should not say what he does not think.

And if only a small body of the people were to do so at once, of their own accord, outworn public opinion would fall off us of itself, and a new, living, real opinion would assert itself. And when public opinion should thus have changed without the slightest effort, the internal condition of men’s lives which so torments them would change likewise of its own accord.

One is ashamed to say how little is needed for all men to be delivered from those calamities which now oppress them; it is only needful not to lie.

- Honesty keeps the campaign on the straight-and-narrow.

In a tax resistance campaign, as in any activist campaign, there are frequently temptations to take short-cuts. Rather than winning a victory after a tough and uncertain struggle, you can declare victory early and hope to capitalize on the morale boost. Rather than doing something practical that takes a lot of thankless hours, you can do something quick and symbolic that “makes a powerful statement.” Rather than fighting for goals that are worth achieving, you can choose goals that are more achievable. Radical honesty gets you in the habit of avoiding temptations like these. - Honesty is itself a good thing worth contributing to.

If you conduct your campaign in a radically honest way, you contribute to a cultural atmosphere of trust and straightforward communication. In this way, even if you do not succeed in the other goals of your tax resistance campaign, you still may have some residual positive effect. - Honesty means there’s a lot of things you no longer have to worry about.

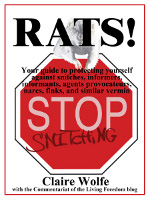

For instance, you don’t have to keep your stories straight, you don’t have to worry about leaks of information that might cast doubt on your credibility, you don’t have to be so concerned with information security, and you don’t have to worry about spies and informers in your midst who might blab your secrets to the authorities. This leaves you free to spend your energy and attention playing offense instead of defense.

Tolstoy’s quotes come from his essay Patriotism and Christianity, and Vaclav Havel’s from The Power of the Powerless. Another good essay on this theme is Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Not To Live By Falsehood.