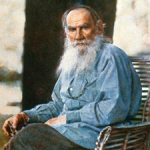

Putting Tolstoy’s Christian Anarchist Principles to the Test

It seems like I’m not the only one going on a Tolstoy binge as we approach the centennial of his death later this year.

Charlotte Aston has written a piece for HistoryToday about the various “Tolstoyan” groups that tried to put his ideals into practice.

There was a time when there was a loose international network of self-consciously “Tolstoyan” communes and other experiments, and Tolstoy’s influence lives on in the inspiration it gave to Gandhi’s satyagraha and to today’s Christian anarchists.

A news report on a proposed new local business tax in Northampton included this note:

But it has emerged that a similar scheme launched in Coventry ended in farce when the body running the project was wound up in the wake of a mass “Axe the Tax” protest, which saw hundreds of recession-struck small firms hauled before magistrates for refusing to pay the levy.

David Williams, a Northampton-based businessman who owned a total of 15 properties which fell under the Coventry BID scheme, said: “It was a total and utter disaster.

Businesses hated it.

At one meeting the people behind it were nearly lynched.

“There were hundreds of businesses struggling in the grip of a recession and then they were asked to pay an extra levy on top.

For some, this was the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

I don’t much cover the constitutionalist “show me the law” style tax protesters here because most of them seem to be motivated not by conscientious objection nor even by a desire to wield grassroots political force against an unjust political order, but by something that strikes me more as a sort of cognitive pathology.

But I try to keep an open mind, and I look out for occasions when the tactics or arguments of this variety of tax protester have something to teach the rest of us.

And, in truth, there is a big grey area.

The British women’s suffragist tax resisters were very much motivated by what they saw as a legitimate constitutional challenge but that the prevailing political order saw as quasi-legal balderdash.

But the constitutional angle was an important rhetorical tool in justifying their resistance to others and in recruiting less-militant feminists.

Here’s an example of an early constitutionalist tax protester in the U.S. — Arthur J. Porth.

Although his techniques and legal arguments put him very much in the constitutionalist “show me the law” tradition, when he was asked to explain his motivations, he put things in conscientious objection terms:

There was nothing that my parents taught me to disobey any tax laws.

However, I can truthfully say that the King James Bible and my Christian teaching have influenced me that it would be wrong to pay money to anybody that would use that money to destroy the nation.

It is not in God’s plan that His people use money for that kind of a purpose.

Thanks to The Anarchist Township for plugging The Picket Line.