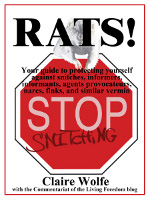

I recently read Claire Wolfe’s new book: Rats! Your guide to protecting yourself against snitches, informers, informants, agents provocateurs, narcs, finks, and similar vermin. In it, she gives some advice that she’s gleaned from her research and from an army of helpful and knowledgeable people — ranging from former law enforcement to attorneys to defendants and interrogatees.

I think it makes for good food for thought, and some of the advice would be very useful to people who haven’t already been hammered with it (e.g. if arrested in the U.S., you do have the right to remain silent and the right to have an attorney present during questioning, and you’d be a fool not to insist on taking advantage of both of those rights). But I also found the book to be disappointing in being often a collection of on-the-one-hand / on-the-other-hand stories. This, I think, is not so much a weakness of the book as a reflection on the difficulty of the subject matter — there is no silver bullet here.

The closest thing to a silver bullet is one that Wolfe never mentions — the radical honesty I wrote about above. A movement like Gandhi’s satyagraha campaign in India defused the danger of snitches and narcs by conducting all of its lawbreaking and conspiring in the open: they would announce “I am going to be breaking such-and-such a law on such-and-such a date in such-and-such a place.” Snitches and narcs had nothing particularly meaty to rat them out about that they weren’t already shouting from the rooftops. (Of course they might still be vulnerable to agents provocateurs, or to people trying to analyze their communications networks in order to disrupt them, or people trying to sow discord, or people hoping to turn key movement members by means of blackmail, or any number of other harmful infiltration strategies — so this, too, is no silver bullet.)

After Gandhi learned about some infiltration by government agents in Indian independence work, he wrote:

This desire for secrecy has bred cowardice amongst us and has made us dissemble our speech. The best and the quickest way of getting rid of this corroding and degrading Secret Service is for us to make a final effort to think everything aloud, have no privileged conversation with any soul on earth and to cease to fear the spy. We must ignore his presence and treat everyone as a friend entitled to know all our thoughts and plans. I know that I have achieved most satisfactory results from evolving the boldest of my plans in broad daylight. I have never lost a minute’s peace for having detectives by my side. The public may not know that I have been shadowed throughout my stay in India. That has not only not worried me but I have even taken friendly services from these gentlemen: many have apologized for having to shadow me. As a rule, what I have spoken in their presence has already been published to the world. The result is that now I do not even notice the presence of these men and I do not know that the Government is much the wiser for having watched my movements through its secret agency.

Such an approach might not work for all varieties of campaigns and actions, but I think for many of them, it might be worth asking “what would we do even if we knew the authorities were watching us and one of us was an informer” rather than guessing “what should we do, since we hope the authorities aren’t watching us and none of us is an informer.” The alternative, of always looking over your shoulder and suspecting everyone you work with, as Wolfe’s book sometimes seems to recommend, seems more a recipe for paralysis.