Some highlights from the recently-released “Progress Update” from the IRS:

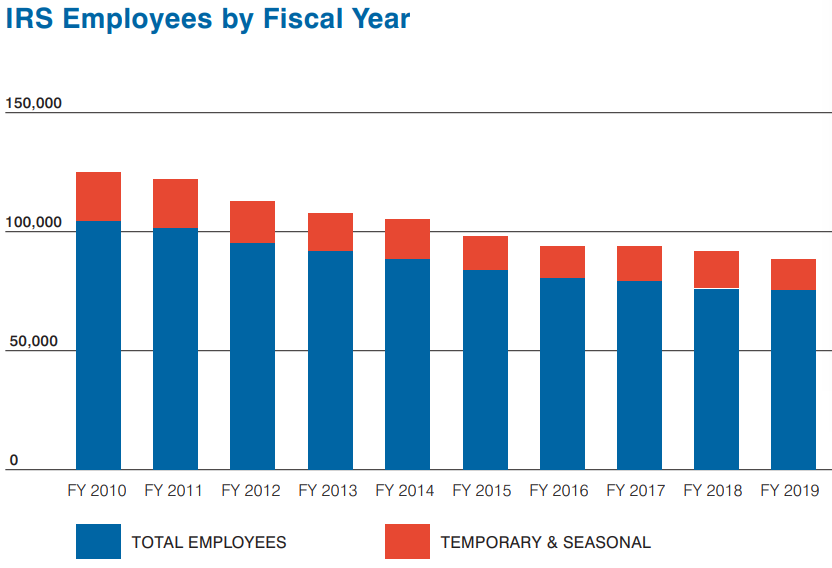

The IRS lost more than 29,618 full time positions … These losses directly correlate with a steady decline in the number of individual audits during the past nine years.

The IRS anticipates up to 31 percent of its current workforce (about 19,719 full-time employees) will retire within , creating a significant risk of a large knowledge and experience gap for the nation’s tax agency.

The report is full of imprecise business-speak and rah-rah codswallop. For example, “In the IRS continued to be extremely active in the enforcement area.” Buried in a table is the news that the rate of auditing personal income tax returns is the lowest it’s been in a decade. From a news report:

The audit rate for individuals declined to 0.45% for , down from 0.9% in , according to IRS data. Even a decade ago, the audit rate was sharply lower than in , when the agency audited about 2.5% of individual returns. The IRS now has fewer auditors than at any point since World War Ⅱ.

One of the enforcement challenges the report names is the “syndicated conservation easement” dodge. Let’s say you own a big hunk of property somewhere. Instead of developing it, you donate the right to develop on the property to a land trust or some such organization that is dedicated to preserving wetlands or the greenbelt or something, and so your property goes undeveloped. That forgone development was worth something, and in giving it away you gave away something of value, so you can get a tax deduction for that. But the scam part comes in by fudging how much the foregone development is worth. You basically pay someone to sign off on a phoney assessment that inflates the value of the donation way beyond what it’s worth. Furthermore you then sell out bits of this potential tax deduction to other taxpayers (that’s the “syndicated” part), who only have to pay in the real value of the property in order to get their cut. So they get a deduction that far exceeds their investment.

But it would take resources for the IRS to figure out the source of the deduction, trace it back to the property in question, figure out what’s fishy about the assessment, get it reassessed, prosecute someone, and so forth. And the IRS is doing just that, with dozens of court cases pending. But they’re popping up quicker than the IRS can suppress them. A recent news article put it this way:

The imperviousness of the scam’s promoters and investors has left tax experts flummoxed. “Boy, it isn’t like the old days, when people were fearful of the IRS,” said Steven Miller, who oversaw enforcement and tax-exempt organizations during his 25 years at the IRS and is now national tax director with consulting firm Alliantgroup. “I’m worried people aren’t afraid of the cop on the beat any more.”

[T]he syndicated deals are structured in a way that insulate the wealthy individual investors, leaving the promoters and outside lawyers to do battle with the IRS. Their fight is fueled with “audit reserves” of as much as $1 million that are set aside as part of every syndication partnership. Some deals even offer “audit insurance” from Lloyds of London to offset disallowed write-offs.