James Warren Doyle, Catholic bishop of Kildare and Leighlin in the early nineteenth century, was an insightful pioneer of the tradition of mass nonviolent civil disobedience that would later be developed by Gandhi and King.

On , Doyle wrote to the pastor of Graig at the beginning of a tithe resistance campaign he was promoting:

The new Government will make a show of vigour, but they will shortly learn that no coalition can ever take place between those who plunder and they who are plundered.

Irish Catholics were required by law to pay a significant tax for the upkeep of the Anglican Church of Ireland (as were Irish non-Catholics), which, though the “official” church, was not the chosen church of most of the country (less than 10% of the population of Ireland were Anglicans). As one historian put it: “The Protestant [Anglican] clergy lived comfortably all through the country, and ministered on Sundays in decent well-kept churches to congregations of perhaps half a dozen, or less; for all which the Catholic people were forced to pay… while their own priests lived in poverty, and celebrated Mass to overflowing congregations in thatched cabins or in the open air.”

Even for members of the Church of Ireland sometimes their only contact with the church was with the tithe collector, as the Church was content to collect its dues without bothering to establish a church house or to deign to send a minister. Indeed, the Church had in many cases abandoned parishes outright (some parishes — one source says 160 of them — had no Anglican parishioners to minister to at all), and instead leased or auctioned tithing rights to professional “tithe proctors” whose profits were limited only by the extent of their ruthlessness.

Adding to the resentment was that while most subsistence farmers were required to turn over 10% of their produce to the Church of Ireland, wealthier (and usually Protestant) owners of grassland for grazing had long been exempt (an early attempt at reform in abolished this exemption, and changed the 10% tithe requirement to an apportioned and more consistent salary). Furthermore, exemptions like these were regional. Presybterian farmers in the North had managed to get potatoes and flax exempt from tithes there, while Catholic farmers in the South still were forced to pay tithes on potatoes, and didn’t grow flax. The whole thing reeked of being a tax on poor Catholics to support Anglican absentee landlords.

And the poor Catholics occasionally made their feelings known. One writer said: “The despoiled peasant is recorded to have now and then revenged himself upon the agent of ecclesiastical extortion by placing that functionary, deprived of his nether habiliments, astride upon a restive horse, with no other saddle than a furze bush.”

In , the new Anglican tithe-proctor of Graigue (a parish of 4,779 Catholics and 63 Protestants) decided to break with the tradition of his predecessor and collect tithes not just from the local Catholics, but also from their priest: one Father James Warren Doyle. Doyle refused to pay, and the proctor seized his horse. A mass civil disobedience campaign that would become known as the Tithe War followed.

Doyle, though a strong foe of tithes, and an early (for a priest) member of the Catholic Association, was of a reformist bent, and from the pulpit he denounced the lynch-mob violence of radical levellers who had banded together in secret societies like the “Blackfeet” and “Whitefeet” (descendants of the Whiteboys) to combat extortionate tithes and rents by force. Eager to avoid the revolutionary excesses he feared from Daniel O’Connell’s popular independence movement, and opposing O’Connell’s periodic campaigns to repeal the Act of Union that bound the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland together, Doyle tried to counsel his friends in government to pass reforms that would take the wind out of the agitators’ sails and preserve the Union. Doyle wrote to Edward Bligh, Lord Darnley, about the state of affairs in Ireland, warning:

The people in parts of this country, of the counties Kilkenny, Wexford, and Tipperary, have, within the last fortnight, assembled in bodies of several thousands to demand the reduction of tithes, and in some places have resolved not to pay any tithe until such reduction is made.

In , O’Connell and other agitators were arrested. This served mostly to make them prominent martyrs and to increase Irish distrust of the government. The law under which they were charged expired during the course of the prosecution, turning the case into an embarrassing sham. Doyle was caught between being sympathetic to the cries for justice coming from his Catholic flock, and trying to dampen an emerging violent rebellion he was certain would be a bloody and disastrous one. He warned:

There is a very extensive combination against the payment of either tithes or a composition for tithes existing at the present moment. Government has assembled in the County Kilkenny a large police force to awe the people into the payment of them. This proceeding will not be successful. The clergy should be instructed to make abatements and keep things quiet; but there is a military spirit in the Government, which creates the necessity for employing force.

On , in Newtownbarry, some 120 British yeomanry fired on a group of tithe resisters who were trying to recapture some seized cattle, killing eighteen people. Doyle had counseled against calling out the yeomanry (“who for many years past have been religious or political partisans,” that is, Orange protestants) to repress the tithe resisters, saying this would needlessly inflame matters and deepen the conflict between the people and the government. Later that year, Irish patriots — hopeless of legal redress (there were no Catholic judges or magistrates in Ireland) — struck back violently, killing eighteen of the yeomanry in a retaliatory ambush. (The numbers of dead and wounded in both of these cases vary with the source you consult.) William John Fitzpatrick (Doyle’s biographer) writes:

A number of writs against defaulters were issued by the Court of Exchequer, and intrusted to the care of process-servers, who, guarded by a strong force, proceeded on their mission with secrecy and despatch. Bonfires along the surrounding hills, however, and shrill whistles through the dell, soon convinced them that the people were not unprepared for hostile visitors. But the yeomanry pushed boldly on: their bayonets were sharp, their ball-cartridge inexhaustible, their hearts dauntless. Suddenly an immense mass of peasantry, armed with scythes and pitchforks, poured down upon them — a terrible struggle ensured, and in a few moments eighteen police, including the commanding-officer, lay dead. The remainder fled, marking the course of their retreat by their blood just as, through the intricacies of English law, the decadence of Ireland had long been traced. In the mêlée, Captain Leyne, a Waterloo veteran, narrowly escaped. A coroner’s jury pronounced “Wilful murder.” Large Government rewards were offered, but failed to produce a single conviction.

Doyle reported another tithe-related killing that took place on : “[A] most brutal murder was committed near Gowran. The victim was employed, I heard, levying distress for tithes. There is a radical error in the mode of conducting the affairs of this country.”

He then published two essays, one of which concerned the tithe question, in the form of a letter to Secretary of the Treasury Thomas Spring Rice. It celebrated historical Irish resistance to mandatory tithes as growing from their “innate love of justice and an indomitable hatred of oppression” and recommended that the current mandatory tithes be replaced by a land tax that would be distributed by secular authorities (for the support of the poor, which subject the first of the essays addressed)

Henry Maxwell, Lord Farnham, attacked Doyle in the House of Lords, saying that Doyle was the head of a tithe resistance conspiracy and was responsible for the Newtownbarry massacre. Fitzpatrick again:

It was quite true that Dr. Doyle had frankly adverted to the tithe system as unjust in principle and odious in practice — as an impediment to the improvement of Ireland in peace as well as in agriculture — as injurious to the best interests of religion, oppressive to the poor, inconsistent with good government, and intolerable to the Irish people. In justification of those strong phrases the Bishop detailed many striking proofs of their truth, from the tithe laws enacted in the Irish Parliament to the Battle of Skibbereen*; and he inquired whether the recent slaughter at Newtownbarry was the effect of a cause different from that which produced the former collisions. The exaction of tithe was incompatible with the peace of Ireland. It had been hated and resisted before [Doyle] was born, and it would be cursed when he lay in his tomb. That the system was not less injurious to agriculture than to peace he clearly demonstrated. He had seen the hay left to rot and the field unfilled rather than pay the tithe of the produce to the parson.

The ministers of the Church of Ireland, Doyle concluded, are “taking the blanket from the bed of sickness, the ragged apparel from the limbs of the pauper, and selling it by auction for the payment of tithe.” This was no exaggeration. People had testified in Parliament to just such Scrooge-like abuse. To the tithe collectors, nothing was too petty to seize, and nobody was too poor to be collected from. One auction notice from Ballymore in read:

To be soaled by Publick Cant in the town of Ballymore on 15 Inst one Cowe the property of Jas Scully one new bed and one gown the property of John quinn seven hanks of yearn the property of the Widow Scott one petty coate & one apron the property of the Widow Gallaher seized under & by virtue of a leasing warrant for the tythe due the Revd. John Ugher.

The opposition to the tithes became increasingly bold and creative. One worried parliamentarian noted in a news account of a mock funeral held in Ireland at which 100,000 people attended, “who assembled to carry in a procession to the grave two coffins, on which were inscribed Tithes and Rent.” The thought that resistance to the taxes levied by foreign, absentee clergy might spill over into resistance to the rents levied by foreign, absentee landlords was frightening to the ruling class.

“But in your opposition to this pest of agriculture and bane of religion,” Doyle wrote to his parishioners, “keep always before your eyes a salutary dread of those statutes which guard the tithe. Let no violence or combination to inspire dread be ever found in your proceedings [alluding to the Whitefeet and other such guerrilla groups]. Justice has no need of such allies. In these countries, if you only obey the law and reverence the constitution, they both will furnish you with ample means whereby to overthrow all oppression, and will secure to you the full enjoyment of every social right.”

Doyle was summoned to London to testify before a hostile “Tithe Committee,” which suspected that rhetoric like the above was given with a wink and a nod to the resisters.

Doyle used the occasion to prosecute the tithe system, giving a history that proved that the tithes had been loathed and resisted from the beginning, that furthermore their original justification had been as money set aside for the poor with the clergy as the administrators of this trust but that over time the clergy had simply taken over the tithes as their own salary, and that outbreaks of paramilitary violence in Ireland over the centuries were empowered by the tithe system.

Asked whether his statements encouraging the Irish to see the tithe laws as unjust encouraged lawless behavior, he replied by reminding the committee of the noble disobedience in their own history: the opposition to ship writs, the revolution of , and so forth. Then, in a passage that reminded me of the rhetoric of Martin Luther King, Jr., he said:

[N]o man ought to be condemned for exhorting people to pursue justice in a certain line, though he may foresee that in the pursuit of that justice the opposition given to those who are proceeding in a just course may produce collision, and that collision lead to the commission of crime; but our duty, as I conceive, is to seek for the injustice, and there to impute the crime … It is to that injustice, and not to those who pursue a just course for the attainment of a right end, that the guilt is to be ascribed.

He was now frankly advocating “passive obedience and nonresistance” — that is, refusal to pay the tithes, and using any legal methods to avoid them, but unresistingly accepting any legal consequences of refusal to pay. “I maintain the right which [Irish Catholics] have of withholding, in a manner consistent with the law and their duty as subjects, the payment of tithe in kind or in money until it is extorted from them by the operation of the law.” Fitzpatrick says that Doyle ended his first day of testimony “by declaring that he would allow his last chair to be seized — nay, sacrifice his life, before he would pay an impost so obnoxious and iniquitous.”

The next day he was asked whether by advising his parishioners to resist the tithes, he wasn’t essentially urging them to steal from those to whom the tithes were due. In response to this question, he brought up the Quakers:

I find in Ireland the religious denomination of Quakers; and they, on account of a peculiar tenet of their religion, refuse to pay tithes in money or kind to the parsons within whose jurisdiction they live; they suffer their cattle or goods to be distrained, and they have never been charged on that account with robbing the parson.

He concluded by presenting the government committee with what must have been a very tempting proposal: why not have people pay their 10% tithes to the government instead of the Church, and then the government can divvy out the money in a more fair manner. Shrewd.

But victory was some ways off yet. Doyle encouraged the resisters to trust in the strength of what Gandhi would later call satyagraha:

The advocacy of truth will always excite hostility, and he who enforces justice will ever have to combat against the powers of this world. I have, through life, regardless of danger or injury, sought to maintain the cause of truth and justice against those “who seek after a lie” and “oppress the weak.” We, who are now embarked in this cause, have to renew our determination, and in proportion as power is exerted against us to oppose ourselves to it as a wall of brass. Let us receive but not return its shocks; for if we abide by the law and pursue truth and justice we may suffer loss for a moment, but as certainly as Providence presides over human affairs every arm lifted against us shall not prosper, and against every tongue that contendeth with us we will obtain our cause.

Peace, unanimity, and perseverance are, therefore, alone requisite, under the Divine protection, to annihilate the iniquitous tithe system, to lift up the poor from their state of extreme indigence, and consequent immorality, and to prepare the way for the future happiness of our beloved country.

In there was another “massacre” when a protestant clergyman led a military force to claim his tithe of growing crops direct from the soil of a farmer. Doyle continued to counsel nonviolence, though his idea of staying within the law got more and more flexible. Fitzpatrick says in an unsourced footnote “A man in confession to Dr. Doyle said, ‘I stole from the pound a cow which had been seized from me for tithe.’ Dr. Doyle made no comment: the penitent thought he might be dozing, and repeated that confession. ‘What else?’ was the sole response.” Elsewhere, Fitzpatrick writes:

Dr. Doyle told the people not to infringe the law, but gave it to be understood that they might exercise their wit in devising expedients of passive resistance to tithes. The hint fell upon fertile soil. An organised system of confederacy, whereby signals were, for miles around, recognised and answered, started into latent vitality. True Irish “winks” were exchanged; and when the rector, at the head of a detachment of police, military, bailiffs, clerks, and auctioneers, would make his descent on the lands of the peasantry, he found the cattle removed, and one or two grinning countenances occupying their place. A search was, of course, instituted, and often days were consumed in prosecuting it. When successful, the parson’s first step was to put the cattle up to auction in the presence of a regiment of English soldiery; but it almost invariably happened that either the assembled spectators were afraid to bid, lest they should incur the vengeance of the peasantry, or else they stammered out such a low offer, that, when knocked down, the expenses of the sale would be found to exceed it. The same observation applies to the crops. Not one man in a hundred had the hardihood to declare himself the purchaser. Sometimes the parson, disgusted at the backwardness of bidders, and trying to remove it, would order the cattle twelve or twenty miles away in order to their being a second time put up for auction. But the locomotive progress of the beasts was always closely tracked, and means were taken to prevent either driver or beast receiving shelter or sustenance throughout the march. This harassing system of anti-tithe tactics, of which an idea is merely given, soon accomplished important results.

Archbishop Whately mentioned some interesting facts. “I have received information which leads me to feel certain, in some instance, and very strongly to suspect in many others, that the resistance to tithe payment in numerous parishes may be traced to the reading of Dr. Doyle’s letter. All composition has been refused. Every possible legal evasion has been resorted to to prevent the incumbent from obtaining his due. A parish purse has been raised to meet law expenses for this purpose, and the result has been that in most instances nothing whatever, in others a very small proportion of the arrears, has been recovered. I know that in one parish some extensive farmers had reduced into writing a form of proposal for a composition, and that the proposal was signed by the parishioners at a fair in the neighbourhood. The fair was held on Saturday; and in consequence, as is supposed, of Dr. Doyle’s letter having been read and commented on next day, instead of his receiving the proposal for composition, notices were served on the clergymen, by those very persons, to take the tithe in kind. He was forced to procure labourers to the amount of sixty, from distant counties, and at high wages, who yet were incapable of obtaining more than a small portion of tithes, being interrupted by a rabble — chiefly women — though men were lurking in the background to support them. He instituted a tithe-suit which was decided in his favour; but, instead of receiving the amount, he was met by an appeal to the High Court of Delegates, and is informed that a continued resistance to the utmost extremity of the law is to be supported by a parish purse.”

The Carlow journals of the day furnish graphic details of a tithe seizure in that town, and of the surrender of the cattle to their owners. The following is culled from “The Sentinel,” a Conservative organ, and cannot, therefore, be suspected of exaggeration:— “Yesterday being the day on which the sheriff announced that, if no bidders could be obtained for the cattle, he would have the property returned to Mr. Germain, immense crowds were collected from the neighbouring counties — upwards of 20,000 men. The County Kildare men, amounting to about 7000, entered, led by Jonas Duckett, Esq., in the most regular and orderly manner. This body was preceded by a band of music, and had several banners on which were ‘Kilkea and Moone, Independence for ever,’ ‘No Church Tax,’ ‘No Tithe,’ ‘Liberty,’ &c. The whole body followed six carts, which were prepared in the English style — each drawn by two horses. The rear was brought up by several respectable landholders of Kildare. The barrack-gates were thrown open, and different detachments of infantry took their stations right and left, while the cavalry, after performing sundry evolutions, occupied the passes leading to the place of sale. The cattle were ordered out, when the sheriff, as on the former day, put them up for sale; but no one could be found to bid for the cattle, upon which he announced his intention of returning them to Mr. Germain. The news was instantly conveyed, like electricity, throughout the entire meeting, when the huzzas of the people surpassed anything we ever witnessed. The cattle were instantly liberated and given up to Mr. Germain. At this period a company of grenadiers arrived, in double-quick time, after travelling from Castlecomer, both officers and men fatigued and covered with dust. Thus terminated this extraordinary contest between the Church and the people, the latter having obtained, by their steadiness, a complete victory. The cattle will be given to the poor of the sundry districts.”

This sort of contest continued for some time, until at last Mr. Stanley, in Parliament, avowed that notwithstanding a vigorous effort made by the Crown to collect arrears of tithe, with the aid of the military, police, and yeomanry, they were able to recover from an arrear of £60,000 little more than one-sixth of that sum, and at an outlay of £27,000. £1,000,000 was voted by the Legislature for the relief of the Protestant clergy. There was also a subscription opened. The Duke of Cumberland, the Duchess of Kent, the Duke of Wellington, Lords Kenyon, Bexley, and even Dr. Doyle’s correspondent, Lord Clifden, contributed £100 each.

The government responded with a repressive Coercion Act, which instituted martial law and banned public meetings. The resisters got creative:

It was illegal to summon public meetings, and so no public meeting was summoned. But it was not illegal for the people of a particular town or parish to announce that on a certain day they were going to have a hurling match, and it was not illegal for the people of other counties and towns and parishes to come and take part in the national sport. It was perfectly plain, however, that the large assemblages that thus came together, met, not for the purpose of ball-playing, but for the purpose of opposing a strong front to the hated tithe system. Men came to these hurling matches to talk of other topics than balls and sticks. These hurling matches became the recognized medium of public opinion, and the public opinion of Ireland was dead against the payment of tithes. That public opinion hinted pretty plainly to those who were willing, for peace and quietness, to pay tithes to their Protestant masters, that such payment would not necessarily secure to them peace and quietness.

The government insisted that there was nothing legal about this “passive obedience and nonresistance” campaign: “[I]t is not compatible with law to evade the performance of the obligations it imposes, and to frustrate the means it provides for their enforcement.” Doyle responded, some years before Thoreau made the same point, that “some laws may be so unjust and so injurious to the public good that ‘to evade them’ is a duty, and ‘to frustrate the means provided to enforce them’ is an exercise of a social or moral virtue.” Still, he insisted on nonviolence:

We bless those who sympathize with us, we shun those who co-operate in the enforcement of an odious law against us; but if any one resort to violence or intimidation whilst our goods are taken from us, him do we disown.

The government eventually (in ) enacted concessions that maintained most of the revenue from the tithe system while making it less confrontational: they lowered the tithe rates by 25% and made them collectible from the landlords as “rent”, not directly from the tenants as “tithe”. Mandatory tithes were nominally abolished in Ireland. The million-pound loan that Parliament had made to cover the tithes in arrears was converted into a gift, an additional quarter of a million was added to that, and the outstanding tithe debts were canceled. This effectively ended the Tithe War. The Church of Ireland was made formally independent from the government, and the mandatory tithes/rents for its support were given a 52-year sunset period, in .

Most of the information and quotes in this Picket Line entry come from The Life, Times, and Correspondence of the Right Rev. Dr. Doyle, Bishop of Kildale and Leighlin () by William John Fitz-Patrick.

* The “Battle of Skibbereen” was an earlier, , tithe-related massacre. In the reports I’ve been able to find out about it on-line, a protestant parson by the name of Morrit, who was the beneficiary of the tithes, actually was the one to give the order to fire. The following poem was an imagining of Morrit’s address to the police:

Brave Peelers, march on, with the musket and sword

And fight for my tithes in the name of the Lord!

Away with whoever appears in your path —

And seize all each peasant in Skibbereen hath!

Hesitate not — the law is on our side you know!

“The Church is in danger!” and yonder the foe!

If women and children expire at your feet!

’Tis a doom good enough for the Papists to meet!

The rebels refuse their last morsel to part —

Let your bullets and bay’nets be fleshed in each heart!

No matter what Priests or Dissenters will say —

I’ll get all my tithes, or I’ll perish to-day!

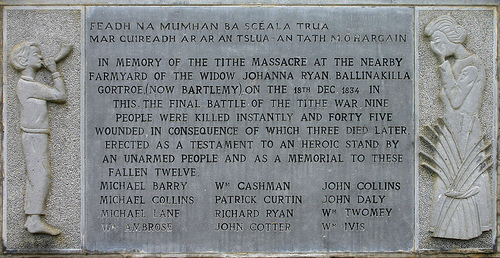

The inscription from a monument dedicated to victims of a massacre that took place during the tithe resistance campaign. Photo by Kman999, some rights reserved.