In the fourth section of the fifth book of The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle continues his examination of the virtue of Justice, this time rectificatory justice.

In previous section we learned that distributive justice is all about maintaining the balance of publicly-allocated goods so that people get what’s coming to them according to their status in the political system they live under. This second variety of justice, rectificatory justice, gives a remedy for what to do when the balance between people is disrupted in the course of their individual interactions.

Say person X and person Y engage in some transaction (either voluntary or involuntary) and this transaction puts them out of equilibrium. Beforehand, the goods X had (Gx) were the goods X deserved to have (Dx) and the goods Y had (Gy) were the goods Y deserved to have (Dy). Afterwards X has somewhat more and/or Y somewhat less, so that Gx>Dx and/or Gy<Dy.

This doesn’t necessarily have to do with physical property. If you slander someone, you take away their rightful goods (in the form of their reputation); if you batter someone, you take away their rightful goods (in the form of their health and well-being); and so forth.

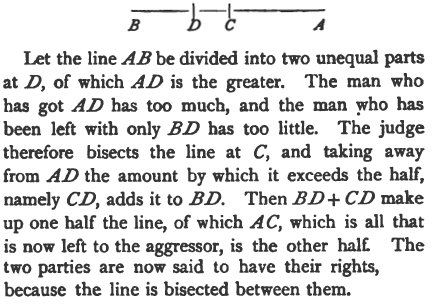

The solution to situations like these is for rectificatory justice to restore the balance. Aristotle uses a geometric metaphor. The judge is like someone called upon to restore equality to a line that has been “divided into two unequal parts” and in order to do so “were to cut off from the greater that by which it exceeds the half, and to add this to the less.”

Illustration showing Aristotle’s geometric illustration of rectificatory justice, from St. George Stock’s Lectures in the Lyceum: or, Aristotle’s Ethics for English Readers ()

In practice it is difficult to achieve this balance — is there really some penalty you can inflict on malefactor Y and award to victim X that is worth the same amount to Y as to X and also the same amount as the original injury? But ideally, two people walk away from the judge with one of them smiling and saying, “huzzah, I have been restored to where I was before I was mistreated” and the other one muttering, “curses, I am reduced to where I was before I tried my sneaky trick.”

Most people expect more from a justice system than this. Rectifying the injustice is only one possible purpose of judgment and punishment; retribution and deterrence are two other important ones. I’ll be curious to see how (or if) Aristotle incorporates these.

Also, remember that this analysis applies to both involuntary and voluntary transactions. It seems as though Aristotle is making the argument that in any voluntary transaction, the parties to the transaction ought to leave it as well-off vis-a-vis each other as they were when they entered it. Anything else implies funny-business and demands rectificatory justice to restore the balance. This has all sorts of ethical and legal implications.

For example, in an agorist economy of unhindered free exchange, it can be assumed that in any voluntary transaction both parties to the transaction end up subjectively better off in its aftermath (otherwise, presumably, they would not have entered in to it). But this, I think, would not have been enough to satisfy Aristotle. I think he would either demand that both parties to the transaction be equally better-off or perhaps that they be better-off in some proportion to one-another that respects some pre-existing proportion. Most transactions in a free economy should be expected to approximate this, but many probably would not (indeed, you would expect people to be constantly looking for opportunities to be on the side of the transaction that gets the bigger-slice of the pie, and for inventive and clever people to be coming up with new opportunities of this sort all the time).

So Aristotle at first glance, I think, is better adapted to support a Marxist view of trade in which class privilege warps the playing field so that “free” exchange works for the sole or lopsided benefit of the owning-class, and that this needs to be rectified by acts of justice (or by radically unwarping the playing field by eliminating the exploiting class). We’ll see whether this first impression holds up as Aristotle’s discussion of Justice continues.

Index to the Nicomachean Ethics series

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics

- Introduction

- Book Ⅰ

- Book Ⅱ

- Book Ⅲ

- Book Ⅳ

- Book Ⅴ

- Book Ⅵ

- Book Ⅶ

- Book Ⅷ

- Book Ⅸ

- Book Ⅹ

- Bibliography