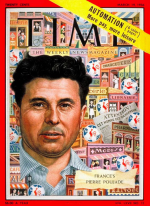

In The New York Times earlier this week, Robert Zaretsky drew some parallels between today’s American “TEA Party” movement and France’s Poujadism half a century ago.

One difference Zaretsky doesn’t mention is that Pierre Poujade’s conservative, populist, pro-imperialist, anti-tax movement actually put some skin in the game, whereas thus far the “TEA Party” has been all talk.

In , Poujade led his “Union for the Defense of Shopkeepers and Artisans” in a tax resistance campaign. “Tens of thousands of taxpayers, mostly in southern France, where his strength is greatest, have refused to make their first installment in payment of taxes on last year’s income.” He also occasionally called for brief strikes in which Poujadists would shutter their shops. In some areas, so it was reported, “unabashed Poujade vigilantes went right on chasing tax collectors down the roads, mobbing police and defying troops assigned to escort them.” According to another account:

The loudspeaker is [the movement’s] symbol and it all started in earnest one bright morning… when a loudspeaker mounted on a truck brought awful tidings to the pleasant little town of St. Cere near Toulouse in south-west France.

“Attention,” it blared. “Attention. The tax inspector is in town.”

There was a rumbling sound as the steel curtains with which French shops are shuttered at night were rolled down all over St. Cere. Then, amidst ominous quiet, a strange procession wound its way through the medieval streets.

At the head of it marched the tax inspector, carrying a bulging briefcase. He was followed by 80 black-uniformed members of the Republican Security Corps with gas masks dangling from their shoulders and submachine guns at the ready. After them, looking just a little scared, came the entire citizenry of the town.

The tax inspector rapped on steel curtain after steel curtain, demanding to be let in to see the books. Nowhere did he get an answer. When they found that even the bistros were locked, the hapless inspector and his guards gave up their mission and beat a humble retreat from St. Cere.

The tax-hating citizens had revolted against the Government of France, and won.

Defiance soon was carried further than that. Angry “Poujadistes” began resorting to physical violence against stubborn tax inspectors who insisted on seeing the accounts. They also took to spiking forced tax sales by refusing to bid until the auctioneer had lowered the price of whatever was up for sale to a laughably small figure. Thus a tax delinquent might buy back his own shop for, say 10 cents. At an auction the other day, a brand-new car went for one franc, or less than one-third of a cent.

The movement has got its members elected to office in almost three-fourths of France’s departmental chambers of commerce. It has secure the support of most of the provincial press, often by threatening mass cancellations of subscriptions, while its own monthly publication, L’Union, has a circulation of 450,000.

Here’s a Life magazine article about the Poujade movement, featuring pictures of some of the resisters, and the detail that “some priests ring church bells to warn of the arrival of the revenuers.” Another brief wire service note shows that the Poujade phenomenon started to cross national boundaries and develop copycat movements elsewhere, perhaps not by accident.

Like the anti-tax, anti-big-government right-wing in the United States today, the Poujadists didn’t seem to mind certain expensive big government projects:

Poujade presented a seven point program to enable France to hold Algeria, hinged on the presence of a large army, strong measures of repression of the independence movement, severe punishment for those who advocate autonomy, and unspecified “reforms” to overcome the unrest of the natives.

When hecklers yelled, “How can you reduce taxes by starting a full fledged war in North Africa?” Poujade’s men quickly silenced them.

The Poujadists briefly formed a political party, and more than fifty of its slate were elected to the Chamber of Deputies (including a young Jean-Marie Le Pen). The movement was short-lived, though. The party was organized on rigidly authoritarian lines and didn’t have much of a platform beyond its complaints.

Poujade decided to bet everything on a single, high-stakes roll of the dice: he’d call for a reenvocation of the States-General (which hadn’t convened since ) as a way of overriding the existing government with a populist revolt. The American parallel would be if the “TEA Party” people were to call for a Constitutional Convention to rewrite the United States Constitution more to their liking. He couldn’t pull this off, and lost credibility. A year after their surprisingly strong showing at the polls, people were already asking “what ever happened to the Poujadists?”