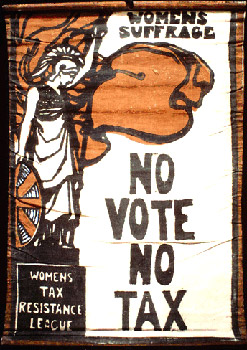

Here’s another look at the role tax resistance played in Britain’s women’s suffrage movement, in an excerpt from Laura E. Nym Mayhall’s The Militant Suffrage Movement: Citizenship and Resistance in Britain, (I’ve added some paragraph breaks to ease on-line legibility):

[Dora] Montefiore argued that because women had no representation, they could not make their positions known to members of Parliament; therefore, women lacked representation and had recourse only to passive resistance. She had outlined a variation on this policy to readers of the feminist paper the Woman’s Signal in , suggesting that should the third reading of the women’s enfranchisement bill then before the House of Commons fail, then those women “who believe in the justice of our demands should form a league, binding ourselves to resist passively the payment of taxes until such taxation be followed by representation.” She implemented this position in her own refusal to pay imperial taxes during the war.

Montefiore was prosecuted for her wartime tax resistance in , and she went on to recommend the tactic in to a controversial new suffrage organization, the Women’s Social and Political Union, as a means of drawing attention to the campaign for women’s parliamentary enfranchisement.

She implemented the protest again, to spectacular effect, during the “Siege of Montefiore,” at her Hammersmith, London, villa in . The house, surrounded by a wall, could be reached only through an arched doorway, which Montefiore and her maid barred against the bailiffs. For six weeks, Montefiore resisted payment of her taxes, addressing the frequent crowds through the upper windows of the house.

WSPU meetings were held in front of the house daily, and resolutions were taken “that taxation without representation is tyranny.” After six weeks, the Crown was legally authorized to break down the door in order to seize property in lieu of taxes, a process to which Montefiore submitted, saying, “It was useless to resist force majeure when it came to technical violence on the part of the authorities.”

Montefiore made her case in the local Kensington News that her refusal to pay imperial tax was linked to her exclusion from the parliamentary franchise. She was quoted in the paper as saying, “I pay my rates willingly and cheerfully, because I possess my municipal vote. I can vote for the Borough and County Councils, and on the election of Guardians,”

Montefiore’s success at mobilizing interest in the women’s cause, and her clear articulation of her protest as one aimed at remedying her exclusion from the parliamentary franchise, popularized the concept of resisting the government as a new approach to campaigning for women’s suffrage.

For previous mentions of tax resistance in Britain’s women’s suffrage movement, see the Picket Line entries from , , and .