I noted that Bradford Lyttle was quoted in an article comparing conscientious war tax resisters with those agitating against requiring anti-contraception employers to be forced to provide health insurance that covers contraception to their employees.

Lyttle is a veteran of a number of pacifist direct action campaigns, and was an important figure in the Committee for Nonviolent Action, an early war tax resistance-promoting group in the modern war tax resistance movement. Today I’ve done a little digging through the archives to find out what I can. Here is some of what I uncovered.

- Lyttle’s college roommate was James Otsuka, also a war tax resister.

- In Lyttle was imprisoned for nine months for refusing to cooperate with the Selective Service (military conscription) Act.

- In , he promoted tactics of nonviolent obstruction (things like blockades, sit-ins, and so forth) in pacifist circles, where many activists considered such tactics to be not strictly non-violent in a Gandhian sense, and many others were content to use more subdued educational and lobbying techniques. “Nonviolent obstruction makes real to the construction workers the issue symbolized by the missile base… the truck driver finds himself faced with the choice of running over the man and killing him or stopping and dragging him out of the way… He sees a man sitting in the dust before his truck who is silently saying to him, ‘Kill me before you build this missile base; kill me before you help kill a million innocent people.’ ”

- In , Lyttle coordinated a peace march from Quebec City, Canada to the tip of Florida. The march, sponsored by the Committee for Nonviolent Action, was supposed to then continue by small boat to the U.S. military base and future gulag in Guantánamo Bay — but the marchers were stopped just off-shore by the U.S. Coast Guard, in order to prevent them from violating a U.S. ban on travel by its citizens to Cuba. “This is the Caribbean Wall,” Lyttle was quoted as saying at the time. “We have the right to travel. It’s as bad as East Berlin.”

- On that march, some of the marchers, including Lyttle, were arrested in Albany, Georgia for “failing to follow an assigned route… disorderly conduct and failure to obey a police officer” — that is, for trying to conduct a racially-integrated peace march through the white shopping district while the local government was trying to quash local anti-segregation activism. They conducted a hunger strike in jail, were released, immediately returned to the forbidden part of town to continue their protest, were jailed again, and finally the authorities relented — labeling their march a “picket” instead of a “parade” and saying that it could therefore go on without permits. This unambiguous (though modest) victory for nonviolent tactics is credited for influencing the adoption of nonviolent tactics in the civil rights movement.

- A second leg of the march went from San Francisco to Moscow, but was halted by Soviet authorities “just 100 yards from the Lenin-Stalin tomb in Red Square” where the marchers were not permitted to speak on disarmament and a nuclear test ban, though they held a silent vigil and handed out Russian-language disarmament, conscientious objection, and war tax resistance propaganda. Lyttle told some curious Russians in Red Square: “I went to jail because I refused to serve in the U.S. Army. I have protested against American rockets aimed at your cities and families. There are Soviet rockets aimed at my city and family. Are you protesting that?”

- Lyttle briefly addressed 200 students at Moscow University, and when the sponsors of the talk tried to stop it after an hour — only 15 minutes of which had been allotted to Lyttle — the students banged on their desks and demanded more time, eventually winning an extra hour and a half for the group and giving them a standing ovation at the end of their talk in which they encouraged the students to buck their government and support an end to nuclear weapons testing. One student passed a note to the demonstrators that read in English, “Do not take any notice of the official line. We are with you.”

- They were unsuccessful in their attempts to demonstrate at the Soviet Defense Ministry, though they had been able to do so at several Western military installations along their path — sometimes courting arrest for doing so, for instance in Key West near the Boca Chica Naval Air Station where they were denied a parade permit and told that they could not carry signs or hand out leaflets, but demonstrated anyway and were arrested.

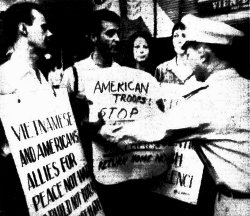

- In , Lyttle was among the Committee for Nonviolent Action protesters who went to Vietnam and tried to hold a vigil in front of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon. The U.S. military promised “counter measures” and the South Vietnamese government organized counter-demonstrators (some of whom were security agents disguised as students) who threatened and threw eggs, light bulbs, garbage, and tomatoes at the pacifists and tore down their signs as they tried to give a press conference. They were arrested before they could reach the embassy and hustled aboard a plane which deported them to Hong Kong. Police also “roughed up several newsmen, seized the cameras of two TV photographers, and briefly detained a third cameraman” while trying to prevent them from covering the abrupt deportation, which helped it make the papers.

A policeman for the South Vietnamese government rips a protest sign from one of the demonstrators. Bradford Lyttle is on the left.

- In , he was arrested during a series of demonstrations at the Pentagon. He was quoted shouting through the bars of the windows of the bus where arrested demonstrators were being held before transport to jail: “Do not work for the Pentagon. Do not work for the government. Do not pay taxes. Join us in the movement against war.”

- Though a pacifist himself, his opponents weren’t interested in playing by pacifist rules. He was knocked out by a punch to the face from a shipyard worker while he was leafletting against nuclear-armed subs, and on multiple occasions the offices where he organized nonviolent actions were attacked by right-wing paramilitary thugs or mobs.

- Lyttle was the first national coordinator of the group War Tax Resistance (the predecessor to today’s National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee).

- In , Lyttle was involved in the anti-war protests in Washington, D.C., as a coordinator for the People’s Coalition for Peace and Justice. The federal government conducted a crackdown, arresting thousands, with the stated goal of tying up anti-war organizers in court. Lyttle, for instance, was charged with assaulting a police officer with “a dangerous weapon” (a bullhorn). The case was later dropped, in part, it was alleged, because the government did not want to be forced to reveal the details of its illegal wiretapping of Lyttle and other organizers.

- In Lyttle participated in the protests surrounding the siege of the home of war tax resisters Betsy Corner and Randy Kehler, which had been seized by the IRS.

- In , he helped deliver medical supplies to Iraq in violation of U.S. law.

- He’s been a regular presidential candidate of the “U.S. Pacifist Party,” which he founded in . In the logo of this party is a peculiar mathematical formula — representing something Lyttle has been promoting for decades now, his theory that a catastrophic nuclear exchange is mathematically certain unless we abandon the strategy of nuclear deterrence / mutually assured destruction, due to the summing up of multiple small but everpresent probabilities of accident, miscalculation, or malice. Such thinking has become more respectable in recent years under the term “black swan theory,” though I haven’t seen much evidence of Lyttle’s particular application catching on.

- He was recently sentenced to a year of probation for his part in civil disobedience actions at the Y-12 National Security Complex (a.k.a. the Oak Ridge nuclear weapons plant).