In the latest U.S. Taxpayer Advocate report to Congress, the Advocate crunches the numbers and says they simply do not support the claims of IRS brass that they’re on top of things and will have the tax return backlog whittled down by next year’s tax season. Looking just at the 1040 (income tax) forms, she writes:

As of late , the IRS had a known backlog of 8.2 million paper Forms 1040, and it may end up receiving as many paper tax returns this year as it received last year (17 million).

Processing has been comparatively slow. As of , the IRS had processed a weekly average of 242,000 paper Forms 1040 over . As of , the IRS had processed a weekly average of 205,000 paper Forms 1040 over . That represents a productivity decline of 15 percent from April to May. If the IRS were to process paper Forms 1040 at its current rate of 205,000 per week over a 52-week year, it would only process 10.7 million returns in a full year. To work through its current Form 1040 paper inventory and the additional Form 1040 paper returns it will receive as we approach the extended filing deadline of , the IRS would have to process far more than 10.7 million returns — and do it in less than half a year. It likely would have to process well over 500,000 Forms 1040 per week to eliminate the backlog this year. The math is daunting.

She notes that the agency does not expect to begin processing ’s paper-filed 1040 forms until , more than five months after those returns started to arrive.

Looking at paper returns in general:

For , the backlog of unprocessed paper tax returns stood at 20 million. At , the backlog had increased to 21.3 million.

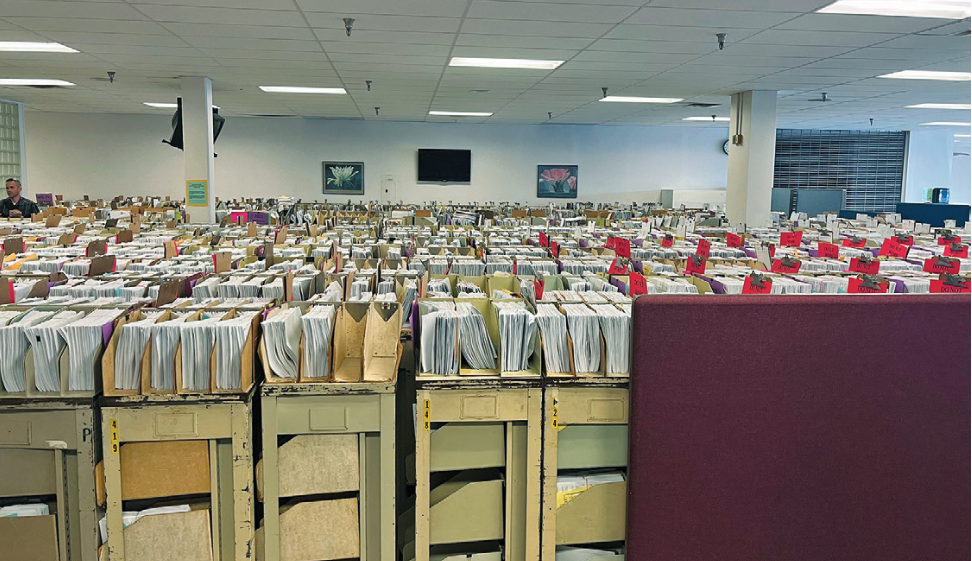

This photograph of the cafeteria of an IRS facility in Austin, Texas, shows some of this immense backlog of paper returns.