A few days back I visited a local memorial to the “first responders” who were killed in the 9/11 attacks. The memorial — called “Standing Tall” — was installed several blocks from my home at a fire station, and features a ring of tall rods, each painted either red or blue and symbolizing a fire or police department member who was killed. Inside the ring is a bare girder that had been part of one of the buildings that was destroyed in the attacks.

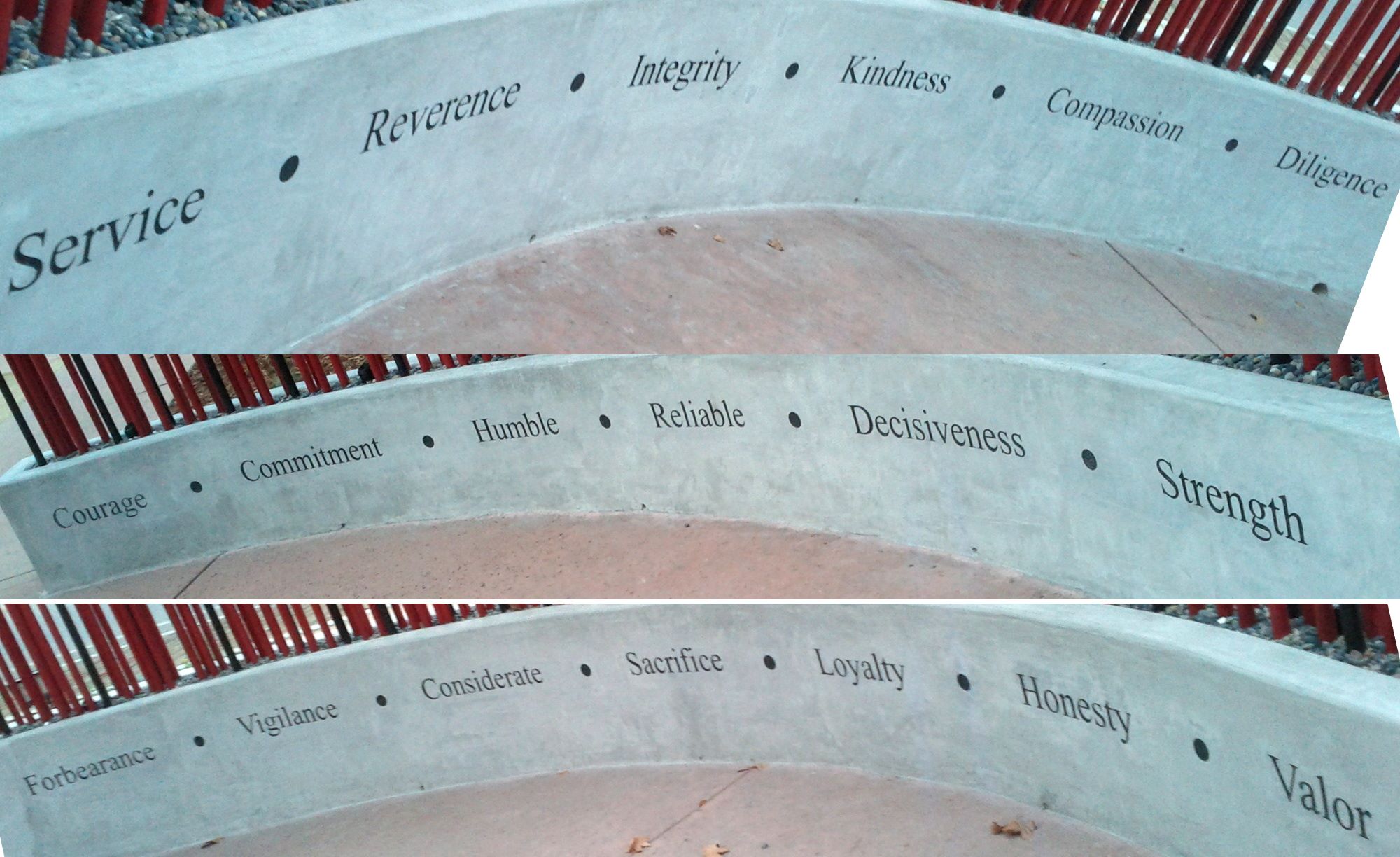

In the concrete base of the ring are several words that I interpreted as representing the virtues exemplified by those killed, or maybe more abstractly the virtues we are to expect from those in the positions they held:

I asked the groundskeeper if he knew why these nineteen words were selected for the memorial, but he didn’t know, and the Google hasn’t gotten me any further. The conceptual design documents for the sculpture don’t list the words or give any indication of how they were chosen. None of the news articles about the unveiling of the sculpture mention them at all. They’re a strange mix of nouns and adjectives, which makes me wonder if they might have been extracted from some other source rather than being selected deliberately and independently.

Why these virtues in particular? Why courage and valor, for instance. Doesn’t valor imply courage? What distinguishes them? Is valor a more public-facing courage? Or does valor imply seeking out and deliberately confronting those important things that are most dangerous, while courage just means facing dangerous things bravely when you happen to encounter them?

Why kindness, compassion, and consideration — why did that set of virtues in particular need to be mapped out with three words’ worth of precision? Can there be commitment and reliability without diligence? integrity without honesty? What does forbearance add in addition to the combination of strength and courage?

These aren’t criticisms, but just some of the thoughts that came to mind as I meditated over the list. I think there may be something to be gained from engaging with lists like these rather than treating them as platitudes and nodding solemnly at them (yes that’s a good word, and that’s a good word…). What are the virtues? Are some more fundamental than others, forming the base that others derive from? Are there virtues we don’t have names for yet? Are there attitudes, or sentiments, or tendencies that are even more fundamental than the virtues, and if we figure those out the rest of the virtues will just come naturally?

Here are a couple more lists: the “four cardinal virtues” of ancient Greece, and Aristotle’s more expansive list:

| prudence | art (know-how) science (deduction) wisdom (good sense, understanding, deliberation) philosophy (reason) intuition (insight, induction) |

| justice | liberality (charity) magnificence (munificence) sincerity (truthfulness, straightforwardness) justice (mercy) |

| temperance (restraint) | temperance good temper (patience, mildness, mercy) |

| courage (fortitude) | courage |

| great-souledness (pride, magnanimity, noble-mindedness) industriousness (ambition) amiability (courtesy, politeness, friendliness) friendship wittiness (geniality, jocularity) shame (a quasi-virtue) |

What first jumps out at me when I put these side-by-side is how much Aristotle improved on the cardinal virtues by adding ones that are conducive to people living together joyfully: things like wittiness, friendship, amiability, good temper, liberality, and sincerity. I hadn’t thought of Aristotle as being so concerned with such things, but this shows he really stretched things in that direction.

He also I think does us a service by emphasizing the intellectual virtues as virtues, and not as we commonly do today: as hobbies and quirks (people who are good at trivia or at Scrabble, or eccentrics), as occupational skills (people with programming skills or a medical degree), or as suspicious and anti-social tendencies.

To know the difference between a good argument and a bad one, to understand basic facts about the world around you, to know about the biases and cognitive illusions we’re all prone to (and how to resist them) — these are important skills to have in order to be a good person. People who neglect to develop these skills because they think they’re unimportant, optional, or unfashionable, become worse people as a result.

Some more lists of virtues:

Ayn Rand was a big Aristotle-head, but she apparently trimmed her list down to three: “Rationality, Productiveness, Pride.”

When I read the Dalai Lama’s books on ethics (see ♇ 12 February and 14 September 2012) I wasn’t doing so with lists of virtues in mind, but in retrospect some that he seemed to focus on included “inner resilience,” “purpose,” “connectedness,” “nying je” (a sort of compassion for which there isn’t a good English translation), “discernment,” “heedfulness,” “mindfulness,” “awareness,” “nonviolence,” “altruism,” “patience,” “self-discipline,” and “generosity.”

Then there are virtues from the Christian tradition. Here are some:

| The Three Christian Virtues (Paul) | The Fruit of the Spirit (Paul) | The Seven Christain Virtues (Prudentius) |

|---|---|---|

| Faith Hope Charity (love) |

Love Joy Peace Forbearance Kindness Goodness Faith Meekness Temperance |

Chastity (purity, honesty, wisdom) Temperance (self-control, justice, honor) Charity (benevolence, altruism) Diligence (persistence, effort) Patience (mercy) Kindness (compassion) Humility (modesty, reverence) |

Somewhere along the line I found “The Seven Virtues of Bushido” according to Nitobe Inazo. These are those:

- rectitude

- courage

- benevolence

- respect

- honesty

- honor

- loyalty

And all of this reminded me of when I was a boy and I had to memorize The Boy Scout Law in order to become a certified Tenderfoot or some such thing. I still know it by heart. “A scout is…”:

- trustworthy

- loyal

- helpful

- friendly

- courteous

- kind

- obedient

- cheerful

- thrifty

- brave

- clean

- reverent

There are some things that didn’t show up on any of these lists and I wonder why, like “curiosity,” “willingness to try new things,” “initiative,” “flexibility/adaptability,” “cooperativeness,” or “gratitude.”

Blessed are the peacemakers, perhaps, but if there is a virtue corresponding to the tendency to intervene in situations to defuse tension and make them more peaceful, I don’t know its name. “Conciliativeness” maybe? The sort of person who tries to keep arguments from turning into fist fights and who reconciles friends who’ve become angry with each other — don’t they deserve a virtue to call their own?

And then there are other qualities, like “enthusiastic,” “good in bed,” “decisive,” “steadfast,” “enterprising,” “visionary,” “tolerant,” “influential,” or “unflappable,” that seem to form such a big part of our pop-cultural sense of whether someone is admirable or not, but that you rarely see on lists like this.

More useful, I suppose, would be the question of what happens after you’ve identified a good set of virtues: how do you then develop them in yourself (or maybe in yourself and others). What parts of this process are pretty much the same across the virtues, and what parts are specific to particular virtues? How much of this can you do on your own with diligent effort, and for how much do you need a tutor of some sort? Can you teach an old dog new virtues, or are some virtues habits you need to get in to while you’re still young?

But this is as far as I’ve gotten today.

I neglected to include Benjamin Franklin’s list when I first compiled this set, but I’ll make up for that now:

- Temperance

- Silence

- Order

- Resolution

- Frugality

- Industry

- Sincerity

- Justice

- Moderation

- Cleanliness

- Tranquility

- Chastity

- Humility

♇ ―