On this date in , The Friend reprinted a section from a booklet by the “Bowdoin Street Young Men’s Peace Society” of Boston.

This was not a Quaker group, but a non-sectarian Christian pacifist group founded around (part of a movement that began to emerge in the United States around ), associated with the American Peace Society, and influenced by the teachings of Thomas C. Upham of Bowdoin College, as given for instance in his The Manual of Peace.

The quoted booklet section is titled “On Preparation for War” and consists of a dialog between “Frank” and “William.” It includes this section:

Frank — But is every body put in jail that refuses to train [in the militia]?

William — No. Many people escape by paying a fine.

Frank — Why then should you not pay the fine?

William — I do not think it would be right. These fines are paid to the [militia] companies, and go to support the military system. I must not escape doing a wicked thing by paying other people to do it for me.*

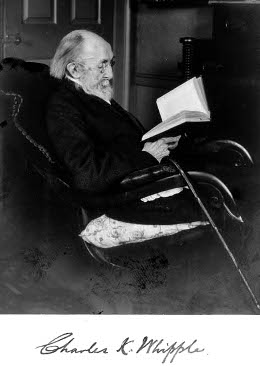

Peter Brock, in his book Liberty and Conscience, attributes the dialog to Charles Whipple. Whipple was also the author of the pamphlet Evils of the Revolutionary War that made an argument for the power of large-scale nonviolent resistance that impressed me as being insightful and ahead-of-its-time. I now see that much of Whipple’s argument in that pamphlet was anticipated in Upham’s The Manual of Peace (and in Jonathan Dymond’s Essays on the Principles of Morality), and so was not so far ahead-of-its-time as I’d thought. Upham’s book also includes the following section on militia fines:

It is possible, that some will make the inquiry here, whether, taking as we do the ground of refusing to perform military duty, we ought to pay military fines? Certainly not, if the fines, as is generally the case, are exacted and are applied for military purposes. As far as principle is concerned, you might as well fight yourself, as pay others for fighting. But if the legislature, taking the constitutional course of exempting from military duty and all military taxation those, who are conscientiously opposed to war, should at the same time impose on the Pacific Exempts, in consideration of their exemption, a tax, which should be expended for roads, schools, the poor, civil officers, hospitals and the like, it might be a question, whether it would not be a duty to pay it. But every one should be well persuaded in his own mind; he must feel well satisfied, that such a payment is not made to contribute, in any way whatever, to the purposes of war. If he can be fully persuaded of this, we are not prepared to say, that there would not be a benefit in such a tax. It would probably tend to satisfy public feeling, and to hush complaints; it would be an evidence of our sincerity; and would discourage those, (for undoubtedly some such would be found,) who might for the sake of saving their time and money, hypocritically pretend conscientious scruples in regard to war. We do not, however, express ourselves on this point with entire confidence; but would merely take the liberty to suggest this view of the subject, as worthy of deliberate consideration. — Whether such a tax could be imposed, consistently with some of the principles of the State and National constitutions may, indeed, well be questioned. But that is an inquiry, which time and the examinations of men learned in the laws will ultimately determine. All we ask now is, that we may have nothing to do with war, either directly or indirectly; and we ask it on the ground of our religion. We do not ask it, because we wish to save our time and save our money, although this would be a reason of some weight, since we believe that time and money expended upon war are worse than thrown away; but because we conscientiously believe wars to be forbidden. We wish to show ourselves good citizens in every possible way; but we ask to be exempted from compulsory disobedience to that great Lawgiver, whose commands should always take the precedence of those of every earthly legislator. If our legislatures choose to increase our burdens in consequence of our religion, whether they can do it consistently with our principles of government or not, we shall consider it of but comparatively little consequence, provided our religious rights are not violated. But this is the point of difficulty. If by paying any tax whatever, on the principle of commutation, (that is to say, on the principle of purchasing an exemption from military duty,) we find that we are promoting, even in the least degree, the cause of war, we cannot rightfully do it. And if we are forced to pay such a tax, then there is a violation of religious right. Going on Gospel principles, no military service is to be performed; no military fine is to be paid; nor is there to be a payment of any commutation tax, imposed for exemption from military services, so long as such payment is in any degree subservient to the purposes of war. But whether this is, or is not the case in any given instance, it is desirable, that each one should examine for himself, and, as we have already said, should be persuaded in his own mind.

Upham later compares taxpaying Christians who oppose war rhetorically, with moderate drinkers who oppose the evils of drunkenness but who aren’t willing to give up alcohol entirely and end their enabling ways:

Professing christians occupy precisely the same position in regard to the great pacific reformation, which must sooner or later inevitably take place, that temperate drinkers but recently occupied in respect to the Temperance reformation, which is now in such encouraging progress. It is but a few years since, and drunkards universally appealed for example and authority to those, who were not drunkards, but nevertheless advocated the right and the expediency of drinking occasionally, only let it be done temperately. Nothing could be effected under such circumstances; it was found necessary, that a new principle should be adopted; before a reformation could reach the drunkards, it was necessary, that there should be an absolute and total reformation of the temperate drinkers. And now we have another great reformation in hand still more important; and in pursuit of it we declaim against military men and military statesmen; but we do not touch their conscience; we do not start them an hair’s breadth from that position of crime and cruelty which we believe they occupy. And why not? It is because they are sustained by professors of religion; it is because while they avowedly drink often and deeply into the spirit of war, the followers of the benevolent religion of Jesus support them by drinking temperately; it is because they see Christians cheerfully paying taxes for their support, and behold Christians in their own ranks, and hear Christians praying for their success. This is the secret, as time will assuredly show, of the great strength of that spirit of war, which has so long pervaded the world.

* The Friend, in a footnote, is careful to distinguish this position from the Quaker point of view on military fines, which is that even if the fines were not paid directly to the military and were to be designated by the government specifically for a non-military, unoffensive purpose, they would still be objectionable: “For the law of man has no right to make us violate the law of God, neither has it a particle more right to make us pay for obedience to God. The principle is wrong, and we cannot comply with a wrong principle and be held guiltless.”