The following article, from the issue of The Vote is part two of a series that started on .

A Red-Tape Comedy. — Ⅱ.

Red Herrings.

The importation into the case of a clause dealing with “foreigners” is

obviously a red herring, and not to be tolerated for a moment. I interpose,

therefore, to point out once again that the words of Section 45 are:— “Any

married woman living with her husband.” My contention is that my client is

“any married woman,” and so long as she comes within these words it does not

matter if she is an aborigine or a messenger from Mars. So this red herring

is abandoned, and another is introduced. The solicitor and the Commissioners

enter into a desultory discussion as to whether the Crown does not possess an

abstract right, under the Constitution, to levy tax on all its subjects. My

client is suddenly appealed to, and is asked to state whether she claims to

be a subject of the Crown, whether she “owes allegiance” to King George, and

whether she has become naturalised in this country!

I am again obliged to object, and I meekly explain to the solicitor that I

have always understood that married women cannot claim to be the subjects of

anybody (except their husbands, possibly) or “owe allegiance” to any

sovereign or government; neither can they possess a nationality or domicile,

nor obtain naturalisation. He seems unable to take this in all at once, but

in a minute or two it dawns upon him, and he says, “Ah! yes; that is so, I

believe.”

The Commissioners appear very bewildered and quite unable to understand why

married women should be in such an extraordinary situation. But as I have

stated that it is so, and the solicitor has agreed to it, they have to let

it go at that.

They then inquire whether my client’s husband is a subject of King George,

&c., and I again object,

explaining that we do not represent Mr. Burn, and therefore cannot speak for

him, and that, whatever he is or may elect to be, it has nothing to do with

our case.

For This Relief Much Thanks.

The solicitor now reads out, for the benefit of the Commissioners and the

Surveyor, a decision given by Lord Cairns, who said:— “I am not at all sure

that, in a fiscal case, form is not amply sufficient. If the person comes

within the letter of the law, he must be taxed. On the other hand, if the

Crown cannot bring the subject within the letter of the law, the subject is

free. Equitable construction is not admissible in a taxing statute, where you

can simply adhere to the words of the Statute.” “Oh, indeed, and so Lord

Cairns said that, did he?” remarks a Commissioner in a tone showing that the

declaration carried great weight with him. He seems quite relieved to find

that somebody has said something definite and tangible, and grateful to the

late lord for giving him such a clear lead. “And you think,” addressing the

solicitor, ”that the Crown has failed to bring the appellant within the

letter of the law?”

“I am of that opinion,” is his reply.

Gloomy Silence.

The Crown has nothing to say for itself now, and its representative, the

Surveyor of Taxes, is reduced to gloomy silence. This is a good thing for

everyone concerned, as had he offered to challenge this opinion, I am fully

prepared to administer to him a dose of Lord Blackburn, who said; “No tax can

be imposed on the subject without words in an Act of Parliament clearly

showing an intention to lay a burden on him. I think the only safe rule is to

look at the words of the enactment, and see what is the intention expressed

by those words.” I should also have felt it my duty to quote Lord Cotton to

him, who was of opinion that “a tax imposed upon the subject ought not to be

enforced unless it comes fairly within the words.” Or I might even have been

impelled to launch Lord Halsbury at his head, who goes further than all the

rest, as he says: “Whatever the real fact may be, I think a court of law is

bound to proceed upon the assumption that the Legislature is an ideal

person who does not make mistakes. It must be assumed that it has

intended what it has said. I think any other view of the mode in which

one must approach the interpretation of a statute would be attended with the

most serious consequences.”

But these weighty pronouncements are evidently not required on the present

occasion, Lord Cairns having proved (to use his own expression) “amply

sufficient.” So I can keep the others in reserve, to do me yeoman service in

some future encounter with the Crown.

The Plight of the Crown.

And now a horrible idea has penetrated the mind of one of the Commissioners.

He is the one who has been so impressed by Lord Cairns’ opinion; but it has

at last occurred to him that this opinion may cut both ways. If

Dr. Burn can secure immunity

on the strength of it, so possibly may her husband, and he inquires

anxiously: “Has the Crown any machinery by which it can reach Mr. Burn in

New Zealand, and levy this tax on him?”

“There is none that I know of,” replies the solicitor. “Mr. Burn appears to

be absolutely beyond the jurisdiction of the Crown, and out of reach of any

fiscal machinery.” “Then what is the Crown to do? On whom is the tax to be

levied? Here you have an income, and nobody can be made to pay the tax!” is

the pitiful lament of the Commissioners.

At this point the expression of these gentlemen irresistibly reminds me of the two officials, Ko-Ko and Pooh-Bah, in Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera of The Mikado of Japan.

It would not surprise me if they burst into “Here’s a state of things! Here’s a pretty how-d’ye-do!”

They seem to see the tax on my client’s income (already standing at nearly £30) slowly but surely dissolving into thin air, like the immortal Cheshire Cat of Alice in Wonderland, leaving behind nothing but a grin.

The solicitor shakes his head gloomily,

the Commissioners are lost in speculation as to who will pay; the Surveyor of

Taxes frantically insists that “Someone has to pay.” To which I reply that I

have no objection, provided the someone is not my client. He can write to New

Zealand and ask Mr. Burn to pay; or, if it is a matter of such great moment,

why not pay it himself!

I point out that my client and I have no interest whatever in this aspect of

the case, and that I do not feel inclined to cudgel my brains to find a

solution of the difficulty into which the Crown has floundered. It must find

a way out as best it can.

Useful Mother-in-Law.

Dr. Burn volunteers the

information that her husband may be coming to England one of these

days; in fact, it would never surprise her to see him walk in unexpectedly.

This seems to afford a gleam of hope for the Crown. And when it further

transpires that should a suitable appointment be offered to her

Dr. Burn may herself cut the

gordian knot by betaking herself to her native land, there seems to be a

feeling that it is her duty to take herself off as soon as possible, and so

relieve the Crown of her embarrassing existence.

“I suppose we shall have to hear something to show that the relations

existing between the appellant and her husband really are of a normal

character,” says a Commissioner to me. “Have you any evidence to give as to

that?”

“Oh yes,” I reply, “we have brought a letter from her mother-in-law.”

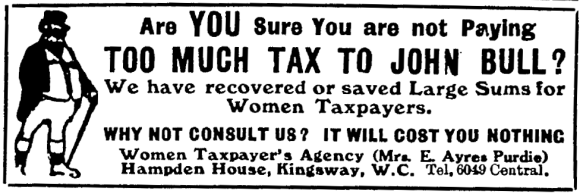

Ethel Ayres Purdie

(To be concluded.)

You’ll have to wait until for the exciting conclusion.