A Red-Tape Comedy.

[Our readers will be specially interested in the following account by Mrs. Ayers Purdie of her successful appeal against the Inland Revenue authorities.]

I desire it to be clearly understood that the following narrative is not an extract from Alice in Wonderland, neither is it a scene out of a Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera.

It is a simple and faithful account of a successful Income-Tax appeal which was heard at Durham on .

The appellant was a Suffragist, belonging to the Women’s Tax-Resistance League and the Women’s Social and Political Union.

I was conducting the case for the appellant, which I am legally entitled to do under Section 13 of the Revenue Act, 1903.

Dramatis Personæ

The dramatis personæ are as follows: Two Commissioners of Taxes, elderly gentlemen, inclining, like all their kind, to baldness; spectacled of course; one of them wearing his spectacles high on his forehead, and looking out at me from under his eyebrows with a pair of piercing eyes.

These gentlemen hear appeals under the Income-Tax Acts, and are the judges therein.

Their decision is absolutely final, except on a point of law, in which case a further appeal may be made to the High Court.

To continue the list, there is also the Clerk to the Commissioners, who is a solicitor, member of a well-known North-country firm.

His business is to record everything, and to help the Commissioners on knotty legal questions; and, finally, the Surveyor of Taxes, who conducts the case for the Crown.

Opposed to all these learned gentlemen are my client and myself.

Unlike all other cases, in which the plaintiff or appellant has the opening and closing of the case, the procedure in these appeals is reversed; the Crown has the first and the last word, which puts a handicap on the appellant.

Accordingly the Surveyor of Taxes is invited to open the proceedings with a statement of his case; and he sets forth that Dr. Alice Burn, of Sunderland, Assistant Medical Inspector for the County of Durham, is receiving an official salary of so much per annum, and, though she has a husband, he lives in New Zealand, according to her own admission, so an assessment has been made on her salary and the Surveyor claims that he is fully entitled to do so.

Then it is my turn to put my case, and I freely admit all the facts as stated by the Surveyor, but challenge the conclusion he has drawn from them; my case being that by Section 45 of the Income-Tax Act of 1842 Dr. Burn cannot be held liable for the tax.

The solicitor reads this section aloud to the Commissioners.

Most women are familiar, since the famous [Elizabeth & Mark] Wilks episode, with the words on which I am relying.

They are, “the profits (i.e., income) of any married woman living with her husband shall be deemed the profits of the husband, and shall be charged in the name of the husband, and not in her name.”

One of the Commissioners asks in whose name was Dr. Burn’s salary assessed, and is told that it has been charged in her own name.

Geographical Separation.

The Surveyor, invited to offer any arguments or evidence to support his case, says that as Dr. Burn is here and Mr. Burn is in New Zealand, she cannot be living with him.

I argue, as against this, that the case really involves a point of law as to what is meant or implied by the words “living with her husband;” that these words must be interpreted strictly in accordance with their legal signification, and therefore I shall contend that my client lives with her husband in the legal sense, though I fully admit the geographical separation.

This term, “geographical separation,” seems to strike one of the Commissioners very forcibly; he repeats it with much relish, adding, “Yes, I can see what you mean, and I suppose you will say that the Crown cannot take any cognisance of a mere geographical separation.

Quite so.”

Apparently he thinks this is a good point, and he glances towards the solicitor, as if wondering how in the world they will get over it.

By this time both Commissioners, who started with the expression of men about to be frightfully bored, have become thoroughly alert and impressed; and the Surveyor appears to realise that his task will nt be such an easy one as he anticipated.

He becomes slightly nervous and confused, a little inclined to bluster, and to take the matter personally, which causes him sometimes to contradict himself and to refute his own arguments.

Being now invited to consider the point about “the geographical separation,” he declines to have anything to do with it, and strenuously denies that any point of law is involved.

He absolutely refuses to consider the matter from this standpoint, and declares that the Commissioners do not take the legal aspect into account in forming their decision.

According to him, this case is purely one of fact, and what the Commissioners have to do is to consider the actual fact, and nothing else.

He knows that if a woman’s husband is at the other side of the world she is not living with him in actual fact, and therefore cannot be said to be living with him at all.

Impertinent Questions

Asked by me to state on what authority he bases this last assertion, he says that he bases it on his own authority; and on his own common-sense.

This leads me to inquire how it happened that, being so fully convinced that my client was not living with her husband, he yet had written to her asking her to furnish him with her husband’s name, address, occupation, the amount of his income, &c. He begs this question by complaining that her reply had been that she could not tell him her husband’s address; and, of course, if a woman could not give her husband’s address it was perfectly plain that she could not be living with him.

I point out that this does not follow, and one of the Commissioners mildly suggests that my client shall explain why she made this reply.

She readily answers that her primary reason was indignation at his questions.

The Commissioner, who seems to be rather human, and quick at grasping things, remarks, “Ah, I see.

You thought he had asked you a lot of impertinent questions, and that was your method of showing your resentment.

Very natural, I’m sure.”

The Surveyor being apparently unprepared with any further argument or evidence beyond the assertion of his own common-sense, it is again my innings.

I take up the tale by reference to the decision in Shrewsbury v. Shrewsbury, which showed that the Crown can only claim to levy tax on spinsters, widows, or femes soles, and my client does not correspond to any one of these descriptions.

I quote precedents set by the Inland Revenue Department on other occasions; as witness the successful objection made to taxation by Miss Decima Moore, Miss Constance Collier, and sundry other ladies, whose circumstances were precisely the same as those of my client.

The Surveyor pretends to be too dense to understand how those ladies whose names I have mentioned could have husbands, and has to have it all minutely explained to him before he is convinced.

A Commissioner asks if I can give any other instances, and I reply, “I am an instance myself, if that will do.

My husband’s business compels him to live in Hampshire, while my own business equally compels me to live in London; but no Surveyor of Taxes has ever ventured to assess me, or to insinuate that I am a feme-sole.

Perhaps you will tell me that I do not live with my husband,” I gently suggest to the present Surveyor of Taxes, who looks as if nothing would give him greater satisfaction if he only dared, but he does not offer to accept this invitation, and the Commissioner hastily says, “I think we are now quite satisfied on the question of precedents.”

I am then proceeding to state that the Crown has itself embodied the correct attitude towards married women in one of the forms issues from Somerset House, in which reference is made to the treatment of “a married woman permanently separated from her husband,” when the Surveyor interrupts — “Are you giving that as evidence?”

“Yes, I am,” I reply.

“Then I shall object to it,” he says.

“I deny that there is any Revenue form having such words upon it, and I object to that statement being received as evidence.”

“As he repudiates the existence of this form, I fear we must uphold his objection,” says the Commissioner apologetically to me.

“Oh,” I exclaim, affecting to be greatly dismayed, “this really was my strongest point.

Do you mean to say you will not admit it because you have not this form before you?”

“I am afraid we cannot, if the Surveyor persists in his objection.

As you see, he is also making avery strong point of it,” is the reply.

The Surveyor intimates that he will persist.

“Very well,” I say, in a tone of resignation to the inevitable; and then there is a short and uncomfortable pause.

The Surveyor looks pleased, as though he fancies he has scored at last.

The other three appear to sympathise with me; even my client begins to look apprehensive, as if she fears I am done for.

Because (as she tells me subsequently) she also thinks I cannot produce this thing, and that I have only been bluffing.

Piece de Resistance

But I make a sudden dive down to my satchel, which lies open on the floor at my feet, and where, unseen by anybody else, the disputed form (No. 44A) has been lying in wait; my last act, before I left London, having been to equip myself with this most important document.

It is laid in front of the Commissioners, and they and the solicitor stare very hard at it, shake their heads over it, and murmur to one another, “Yes, it says so, right enough,” and “This settles it, don’t you think?”

When they have quite done with it, the Surveyor has his turn, and he pounces upon it, examines it intently, up and down, and all round, as if to convince himself that there is no deception, and that it is not a conjuring trick.

(I must do him the justice to say that I honesty believe he has never seen or heard of this form before, as it is very little used.)

It is now fairly evident that my pièce de résistance, No. 44A, has clinched the business, as I knew it must, and that my case is as good as won.

But the Surveyor starts off desperately on a fresh tack.

“Even if those words are on this form,” he says, in portentious tones, “it does not follow that what is stated on official forms is necessarily in accordance with law.”

“I quite agree with you there,” is my cordial reply.

“If everything that is contrary to law were to be eliminated from the form, there would be very little left.

But you may take it that the part I am relying on is perfectly good law,” and I glance toward the solicitor, who nods his assent.

“Then I shall maintain that you cannot reply upon what any form says, because the Board of Inland Revenue can at any moment alter the wording of a form,” says the Surveyor.

“Yes, the Board always have the power to vary the forms when they think fit,” echo the Commissioners.

“But they have not yet altered this one,” I object, “and you cannot raise a valid argument against it by simply saying that it might be something different if it did not happen to be what it is.

The Board have put these words on this form to serve some particular purpose of their own; and it so happens that it equally suits my purpose to make use of them here and now.

It is ‘up to you’ to decide this case in one way or the other; but the Crown is not going, as hitherto, to claim to have things both ways.”

“Both ways, indeed,” laughs one of the Commissioners.

“Why, the Crown will have it three ways, if it is possible.”

“And I am here to show the Crown that it is not possible,” I retort.

The Surveyor is disinclined further to contest the validity of Form No. 44A; but the solicitor seems to be uneasy, as if he feels that the Crown is losing prestige, and that somebody must make the running for it.

So he starts to read an obscure and wearisome section of the Income-Tax Act relating to “foreigners” coming to reside in this country!

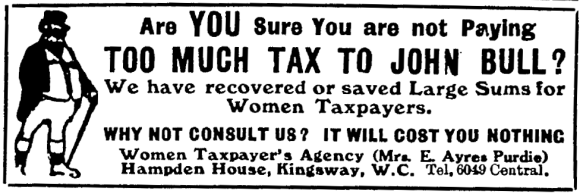

Ethel Ayers Purdie.

(To be continued.)

I’ll post the second part of the above article on .

Tax Resistance.

Women’s Freedom League.

After inexplicable delays, the representatives of the Law have finally made up their minds to wrestle with the case of Dr. [Elizabeth] Knight.

On , the Hon. Treasurer of the League received a call from a gentleman who embodied in his person the might, majesty and power of the London County Council, and the Court of Petty Sessions, and showed a desire to annex Dr. Knight’s property in lieu of the £2 5s. which she declines to pay.

It is hardly necessary to tell readers of The Vote that he got very little satisfaction out of his visit, seeing that no fine was forthcoming, no property could be seized, and no information was vouchsafed.

After some slight altercation, and an almost pathetic attempt at persuasion, in neither of which was any advantage gained, the Law retired, to return at some future period (unstated) with a warrant for the arrest of the smiling culprit, who declined, in accordance with the attitude taken up by the Women’s Freedom League, to furnish any information or facilities to the agents of the Government.

Miss Janet Bunten, whose goods were seized in Glasgow at twenty-four hours’ notice, was absent from home with the women marchers at the time that the Government executed its mandate for the distraint.

We are glad to be able to say that a staunch friend of Miss Bunten’s, who belongs to the Women’s Social and Political Union — some of whose members were in the same plight — bought in the goods for her.

Women’s Tax Resistance League.

Last week Mrs. Kineton Parkes spoke at Manchester and Leeds, and on Mrs. [Caroline] Fagan spoke at Woking on the subject of Tax Resistance.

New members joined the League at each place.

On , a Tax Resistance meeting was held under the auspices of the Hampstead W.S.P.U., and was presided over by Mrs. [Myra Eleanor] Sadd Brown.

Mrs. Kineton Parkes and Mr. Mark Wilks were the speakers.

Particulars appear in another column [sic] of the Caxton Hall Reception, on , to Mr. Mark Wilks.

Great interest will also be attached to the account of the case of Dr. Alice Burn, Medical Officer of Health for the County of Durham.

Mrs. Ayers Purdie appeared for her in Durham, and won our case against the Inland Revenue — a notable triumph for the Cause.

The Women’s Tax Resistance will join the Marchers at Camden-town on and proceed with the John Hampden Banner to Trafalgar-square.

Enthusiastic Reception to Mr. Mark Wilks.

Two meetings; the same hall; the same man as the centre of interest; yet what a difference!

In , Mr. Mark Wilks was in prison, and the Caxton Hall rang with the indignant demand for his release.

In Mr. Mark Wilks was on the platform, and the Caxton Hall rang with enthusiastic appreciation of his service to the Woman’s Cause.

“It is fitting that on this memorable day, when the Government has been defeated in the House of Commons, that we should meet to celebrate the defeat of the Government by Mr. Mark Wilks,” said Mr. Pethick Lawrence.

One had only to scan the platform and glance round the hall on to note that the Women’s Tax Resistance League has the power to call together men and women determined to do and to suffer in order to win the legal badge of citizenship for women and the amending of unjust laws.

Mr. Wilks and his brave wife, Dr. Elizabeth Wilks, had a fine reception, and their speeches were clear, straight challenges to all to carry on the fight.

“We must never tire,” said Dr. Wilks, as she showed the injustice of the working of the income tax methods of collection, and told heartrending stories of the betrayal of young girls, “until we have won sex equality.”

“If anyone fears that he has not courage to go to prison he will soon find, when he is inside, that one of its peculiar characteristics is to produce a determination and courage undreamed of to resist, not its discipline, which is a farce, but its tyranny, which oppresses the weak, and vanishes like the mist before the strong.”

Thus, Mr. Mark Wilks; and, having been inside himself, he declared that he was most anxious that Captain Gonne should enjoy a similar experience, because he is resisting taxation, largely on account of the White Slave Traffic.

“They seized an obscure man; let the important ones be seized.

They did not know you were behind me; we will show the one or two men who really stand for the great scheme we call ‘Government,’ that we are behind Captain Gonne.

I have been inside and know how to do it.

Play the band and cheer.

The effect is electric!”

Mr. Robert Cholmely, M.P., from the chair, blessed the Tax Resistance movement; Mr. Pethick Lawrence acclaimed it as part of a militant policy against a Government which abandons its Liberal principles and finds itself defeated; Mrs. [Charlotte] Despard rejoiced that the best men were standing by the women; Mrs. Cobden Sanderson pleaded for more recruits for the League to help it to find more Mark Wilks; Miss Bensusan and Miss Decima Moore delighted and amused everyone by their recitations of imaginary Antis and real tax collectors.

A notable gathering on a notable day.