The tax resistance campaign targeting the aspects of the Education Act that allowed for taxpayer funding of sectarian education continued to heat up in nonconformist circles in Britain in .

A story in the Nottingham Evening Post told of three resisters who appeared at Shire Hall in Nottingham, summoned for non-payment. Each explained that they were willing to pay the bulk of their rates, but would withhold the portion they believed would go to sectarian education. The magistrates said nothing doing, and issued distraint warrants for the whole amount.

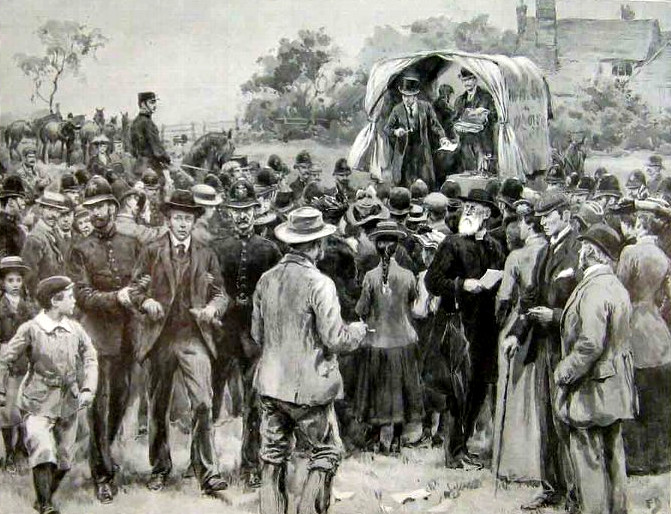

Below that article, a second one concerned an auction at which the goods of 23 resisters from Long Eaton were sold as the gains of previously-granted distraints. “A good deal of interest was manifested in the proceedings,” says this report, from “a crowd of some 150 persons, chiefly women and youths, with a sprinkling of the leading Nonconformist representatives in the town.” The people whose goods were sold are listed, along with the amounts they had refused to pay (ranging from one shilling, one pence to eight shillings, three pence):

As soon as the auctioneer put in an appearance the passive resisters cheered ironically and with frequent interruptions the various articles, including boots, sewing machines, bicycles, gold and silver watches, and two volumes of an historical work, were disposed of.

The whole of the goods were brought in by Mr. J. Winfield, jun., C.C., and the aggregate amount of the sale was £17 17s. 10d.

The proceedings were very formal, and there was practically no bidding, all the transactions being conducted inside the vestibule of the police-station.

The crowd kept up continual hooting, but with the exception of one demonstrative young lady, who threw a small bag of flour at the auctioneer, and missed him, there was practically no disorder.

A detachment of the county constabulary under Deputy Chief Constable Airey, had concentrated at Lower Eaton, but their services were not required.

An effort was made to organise a meeting in the Market-place, but the crowd declined to leave the neighbourhood of the police-station until Mr. Webster [the auctioneer] left, and during the period of waiting the Rev. F.J. Fry, of Nottingham, entered his strong protest against the iniquity of the Education Bill, and the Rev. J.T. Hesleton, and the Rev. — Cottam addressed brief observations, expressing indignation that they should be required to pay such a rate.

Below that, a third article concerned the cases of nine people, including resisters but perhaps not exclusively so, from Hathern, who were tried at the Loughbourough Petty Sessions. “The court was pretty well filled with Nonconformists from Loughborough and surrounding districts, including several Baptist and other ministers.” In this case, the court allowed the defendants to go on at greater length about their grievances, and the overseer was willing to accept partial payments, though the magistrates overruled this and issued distraint orders for the full amounts.

A new Citizens’ League was forming in Nelson to coordinate resistance to the Education Act, according to the Burnley Express and Advertiser. The Rev. J. Hurst Hollowell spoke, saying, among other things:

[I]f they paid for such authorities, such finance, such management, such superstitious teaching — they were paying for such things under this Act — they would make themselves responsible for such things.

They could not say it was the County Council or the Borough Council that was responsible — it was the people if they paid for it.

Parliament had no moral right to lay that charge upon them.

Surely there was a limit to what a country would stand from Parliament.

They were now at the parting of the ways, they were in a temper of revolt, and may God speed the right.

They were trying by passive resistance to break the law of an unprincipled Government, and a contemptible tyranny — (hear, hear) — and he hoped they in Nelson would come forward in the spirit of those who had gone before.

Rev. A.S. Hollinshead took that ball and ran with it, saying that “[h]e should regard himself as one of the basest of cowards, and unworthy of the noble people who worshipped in that building [the Carr-road Baptist School], if with his own hand he paid the money that was to keep up that damnable injustice.”

A resolution was moved, seconded, and unanimously carried declaring the meeting’s “fullest sympathy with the Passive resistance movement for refusing that portion of the education rate which is to be applied to schools under sectarian management.” A second resolution led to the forming of the League, formed in the now-usual way, with members both of tax resisters and of sympathizers with the resisters who for whatever reason could not resist the rates themselves.

As lengthy as these excerpts are turning out to be, I should point out that I aborted my search early when I realized what I was getting in to (there is an enormous amount of material about this campaign in the British newspaper archives), and I’m omitting a tonne of stuff from what I did collect. Just the competing letters to the editor from duelling Christians tossing Romans 13 and Acts 5 back and forth at each other would probably fill a volume.

In The Derby Daily Telegraph of , John Wenn wrote in to say that he had learned that someone had anonymously paid the portion of his rates that he had refused to pay. Seeing this as an attempt to extinguish his passive resistance, he fought back with this declaration:

I give this public notice that the amount paid for me will be sent to the Derby and District Passive Resistance Fund, and that any such gratuitous insult offered to me in the future, and for so long as the obnoxious Act remains unamended, will be treated in the same way.

Let the busybodies, therefore, know that by such conduct they are promoting, not stifling, passive resistance after all.

The Western Daily Press of Bristol, in its issue, printed a letter from Richard Glover which gave an update on the campaign there. Excerpts:

between 60 and 70 persons of highest Christian character, kindliness, and usefulness were brought before the magistrates, and subjected to the ignominy of punishment as law breakers.

25 of similar character have been similarly treated.

Two or three hundred more of our very best citizens are to be similarly dealt with.

This sort of thing is to be repeated six months hence, on doubtless a much larger scale; for while many Nonconformists do not feel free to refuse lawfully imposed rates or taxes, many whose consciences do not bind them to refuse will be certain, from motives of admiration and sympathy, to take their stand by the side of those who suffer for conscience sake.

Then, in its issue, The Western Daily Press reported on “the third detachment of passive resisters” to go to court in Bristol. “A knot of spectators who evidently sympathised with the defendants stood in the vicinity of the police court in Bridewell Street, and the seats in the court allotted to the public were filled.”

The paper listed 44 of the defendants, alongside the amounts they were being summoned for (ranging from £0.2.3 to £2.16.6½) and said there were 20 to 30 more that they did not manage to learn about. The magistrates seemed to be sympathetic, though they were unwilling to deviate from the law, and they allowed each defendant to vent in turn. Most simply repeated one or more of the usual grievances against the act. One, a Mr. Belcher, added that “They could get no respectable auctioneer to take any part in it. (Laughter.) With regard to the magistrates, those who rose above mere officialism declined to lend a hand to carry it through.” That aside, at the end of the hearing (which resulted in the usual distraint orders), the secretary of the local Citizens’ League thanked the magistrates for their atypical courtesy.

The following article covered a protest meeting held to prepare the resisters for the next phase in the local campaign: this round of summonses and hearings before the magistrates was complete, and next the property seizures and auctions would begin. Hymns were sung on the way to the meeting (“Hold the fort” and “Onward Christian soldiers”) and the national anthem was sung to end it, and in-between some of the more prominent resisters gave speeches meant to inspire continued resistance from what the paper described as “a large congregation.”

Below this an article described an auction at Axbridge at which the property of four resisters was being sold for their rates. This sale seems to have attracted less attention and less opposition. In at least one case, one of the items auctioned was purchased not on behalf of the resister it was taken from, but by “an opponent of the passive resisters.” The auction was followed by a protest rally at which speeches were given to a modestly-sized crowd.

A one-paragraph note below that mentioned six resisters summoned to the Trowbridge petty session, and then followed one last article in the sequence which concerned distraint summons issued at Cambridge.

An editorial in the Coventry Herald reported that “The Passive Resisters of Coventry have had the unpaid remnant of their rates — corresponding to the amount devoted to the support of denominational schools — paid for them; and, as is to be expected, they do not like it.” The article tweaked the nonconformists for this, saying that while their hoped-for martyrdom had been spoiled, their consciences had been spared and so perhaps they should be pleased.

The editorial shrewdly analyzed this and was not content to dismiss it as hypocrisy. Instead it concluded that this revealed that conscientious objection was not really at the root of the passive resistance campaign, but rather the campaign was an attempt to use civil disobedience to provoke a crisis that would pressure the government to rescind the offensive parts of the Education Act.

The editorial gave some estimates about the size of the movement:

The passive resisters who have had their rates paid for them [in Coventry] number about seventy; amongst them are most of the local Nonconformist minister.…

It appears from statistics giving the progress of passive resistance that the number of summonses issued throughout the country slightly exceeds 3,000… Three thousand is a considerable number, but the Nonconformists of England are still more considerable; they claim to be half of the professedly religious part of the nation.

The Cambridge Independent Press reported on the seizure of goods from 34 resisters .

[T]he Assistant Overseer… spent over five hours on Monday in a task, the unpleasantness of which was only lessened by the entire absence of any animosity or opposition on the part of the Passive Resisters.

When he commenced his round, Mr. Campbell was accompanied by the Warrant Officer, Acting-Sergt. Fuller, but so courteous was the behaviour of the persons visited that there was not the slightest need of the police officer’s services, and they were dispensed with before the work of collecting the goods had been completed.

The article goes on to describe the goods seized — “a miscellaneous collection” — including bicycles, violins, opera glasses, and a case of condensed milk. One resister announced that he “intends to have his silver cake basket, which was taken, engraven with the date of this and all subsequent seizures.”

This was immediately followed by an article that reflected on the persecution meted out a generation or two before to nonconformists who refused to pay the “Church rates,” including a Baptist who had had goods seized and a Quaker who had been imprisoned.

Among the other articles on the same page touching on the passive resistance movement was one concerning a sale of goods seized from three resisters at St. Ives. An auctioneer was brought in from out of town, “it being understood that local auctioneers declined to conduct the sale.” Police were in attendance, but no disturbances were reported, “though the auctioneer was subjected to a good deal of banter and chaff.”

The sale to a great extent was a farce, as no one could hear the bids, but it was understood the goods were bought in by persons employed by the Passive Resisters…

After the sale there were loud cries for the auctioneer, but he remained in the Police-station, and after waiting about for some time the crowd went with the promoters to a meeting on the Market-hill.

The auctioneer was subsequently escorted by the police up a back road to the railway station, where there were ten members of the Police Force to see him off, and others to travel with him.

The Market-hill meeting featured the usual speeches, a motion of support for Passive Resisters, and also “a vote of thanks… to the magistrates and police for the courteous way in which the cases were heard, seizures made, and sale conducted.”

An article following this one concerned the “second batch of Passive Resisters at Wisbech,” ten of them, summoned to Police-court. The magistrates in this case seemed also to be conciliatory, and agreed to make out a single distress warrant for all of the resisters in order to reduce the costs. Following this was a brief article about summonses issued against eleven resisters in Huntingdon, including two sisters of a parliamentarian.

The Western Daily Press of covered the cases of a dozen or so resisters who were summoned to the petty sessions at Weston-super-Mare. In these cases, the overseer had refused to accept partial payments and so was seeking distraint warrants for the whole of the tax.

The magistrates requested the police to turn out anyone who behaved disorderly, and the sergeant remarked, “This is not a theatre” to the large number of interested spectators.

Below this was a similar article about seven resisters summoned to the Stroud petty sessions (in this case, partial payments had been accepted, and distraint orders were issued for the remainder). The article noted that the resisters who had been summonsed the week before “have had their rates paid, whether by friend or foe is not known.”

The edition of the same paper covered the Axbridge petty sessions, at which eight resisters were summoned. A new legal tactic was tried here:

[Harry Cook] Marshall objected to three of the magistrates, viz., the Chairman, who was on the County Education Committee, and two others on the ground of prejudice.

Mr C.L.F. Edwards: To whom do you object?

Mr Marshall: I shall hear whether my objections hold good, and then I can mention the names

The Clerk said they must hear more of the objection before it could be considered.

Mr Marshall: They are prejudiced because I am a Nonconformist.

I have been sworn at and blackguarded by one of the magistrates on account of my Nonconformity, worse than I have ever been insulted in my life before.

(Cries of “Shame” were instantly suppressed by the police.)

The objection didn’t go anywhere with the magistrates. Neither did this one:

Mr Marshall said the summons was an absolute lie, inasmuch as he had only refused a part of the rate.

They had come to a court of justice and they expected the truth.

As that (pointing to the summons) was to be handed down as a heirloom in his family, he would like the truth put on it.

(Applause.)

Following this was an article about eleven resisters summoned at the Westbury petty sessions. “The court was crowded and several times there was some excitement.… Subsequently a meeting was held outside the Town Hall, and protest speeches were made.”

A third article covered “[s]ome 34 passive resisters of Cheltenham” who “were the centre of attraction, both in and outside the court, by large crowds.” The usual complaints were aired, the usual distraints granted, and “[i]n the evening a meeting was held in protest…”

A fourth article concerned two resisters summoned to the Chard Guildhall; a fifth concerned several resisters who tried to state their cases at Branksome, including this one:

Mr. Norton, another well-known magistrate, emphatically declined to enter the dock and be treated as a criminal, but was told he would not be heard unless he did.

This aroused the indignation of the crowd, who hooted the magistrates, and they straightway adjourned the case.

Two additional brief articles concerned a property seizure and an auction:

Goods Seized at Birmingham.

At Birmingham the police levied further distraints upon passive resisters.

When they reached the house of the Rev. J.O. Dell, who is the leading spirit in the passive resistance movement, that gentleman called his family together and invited the officers to join with them in a short service.

The 91st Psalm was read, and all present knelt down whilst Mr O’Dell prayed.

The police seized a piano, and when this had been taken into the street they were asked to stand themselves around it, the group being then photographed.

Scene at an Auction.

During the second sale of passive resisters’ goods at Cambridge , a crowd of young men twice tried to rush the auctioneer, but were frustrated by the police.

About 36 lots were sold, the goods being bought in.

The Manchester Courier and Lancaster General Advertiser of included a set of articles on the campaign. The first considered “[t]he last batch of passive resisters in Altrincham” to be summoned before the magistrates, who refused to combine their cases into a single distraint order (which would have reduced expenses) as another court had done. F. Cowell Lloyd, “chairman of the Altrincham Passive Resistance League,” disrupted the court by standing up to complain that someone had been paying some of the resisters rates for them. The usual protest meeting was held afterwards.

The second article told the same story of the cases tried at Branksome that the The Western Daily Press covered, above. The third covered the J.O. Dell or J. O’Dell case (this article, to confuse the matter further, calls him “J. Odell”). A forth concerns “the first batch” of resisters to be summoned in South Manchester, says that there’s at least one such resister in North Manchester (which had not yet attempted to collect rates), but that “[t]he overseers in the Manchester township have not as yet been troubled with the passive resisters.”

Some excerpts from article #5:

A Lady Resister’s Threat

Exciting scenes were witnessed at Willesden , when close upon 200 passive resisters appeared in answer to summonses.

The court was crowded, while outside 500 or 600 persons assembled, including a number of ministers.

During the hearing of objections the crowd frequently burst into applause, and it was only after a threat to clear the court that the interruptions ceased.

Amongst other objectors who came forward were two ladies, one of whom said she felt it incumbent upon her to always appear every six months and give as much trouble as she possibly could in the collection of the infamous rate.

The set of articles concludes with these two brief notes:

In Reading, “the passive resisters” have been allowed to pay the portion of the rate not objected to, and the authorities are delaying any steps to recover the balance, although it has been long overdue.

Some “resisters” at Tilehurst, a suburban village near Reading, were to be proceeded against, but the magistrates directed that the signed authority of the overseers must first be obtained.

The overseers, however, unanimously refused to give their consent in writing.

The Essex County Chronicle for carried several articles about the passive resistance struggle:

- “The Grays and District Passive Resistance League is reported to be growing daily in numbers,” read one.

- Another reported on the summonses of six resisters from Tiptree for amounts ranging from eight shillings and change to a little over ten pounds. “There was a crowd in court, including several Nonconformist ministers.” The paper prints a representative transcript of what took place in the courtroom, which is unusually jovial in its sparring, and more than usually eloquent in the way the Education Act was denounced, but for all that adds little to what I’ve already excerpted.

- The cases of 34 resisters were heard at the North London Police-court, and distress warrants were issued in each case.

- Heddington Petty Session heard the cases of three resisters. Afterwards “a protest meeting was held in the road near the Bell Hotel [at which v]igorous addresses, condemning the Act, were given… [And it was] alleged that the magistrates that morning had not given fair play to the passive resisters.”

- A resister was summoned to the Chelmsford Petty Session, who was particularly defiant, saying in part: “And pay, I never will. You can have my body and my goods, and I will go to gaol first. [Applause.] I know what my forefathers paid for my liberties, and do you think I would come to England” [he being from Scotland, apparently] “and give those liberties away? Never! I want to hand down the liberties to my family as they have been handed down to me.”

- An auction of seized goods was held at Romford.

“About 100 persons assembled, and the proceedings were very orderly.”

The meeting passed its usual motions of indignation, and was unusual for entertaining a dissenting voice: a vicar who defended the establishment Church, saying “that Church people contributed fully sufficient to pay the cost of teaching their children.” Some “good natured argument” ensued.A family Bible, which fetched 15s., drew the remark: “Distrained for religious education.”

After the sale a meeting was held in the Market-place.

Mr Walter Young, LL.B., presided. He said the police of the country were with the passive resisters, and did not like the dirty work which had been thrust upon them. Dr. Clifford, their leader, regretted his absence, and had written that the movement was only in its beginning.

- Two resisters were summoned to the Braintree Petty Session. One concluded by saying “at Braintree they had a great aversion to rowdyism. The resisters hoped that none of the scenes which had taken place elsewhere would occur at Braintree. [Hear, hear.]” A subsequent Braintree Citizens’ League meeting enrolled five new members, bringing their total to 55.

- “A large company assembled” at the sale 55 lots of distrained goods at Brentwood.

A new element I see for the first time in this article is this:

At the conclusion of the auction “Cheers were given for the passive resisters and for the police, and ‘God save the King’ was sung.” The usual indignation meeting was held after.A yellow banner with “We will not submit” in red letters was unfurled, and was received with cheers.

The Bucks Herald of covered “the inaugural meeting of the North Bucks [and Aylesbury] Citizens’ League, formed in connection with the ‘passive resistance’ movement”. The acting secretary explained that 50 people had joined up before this first meeting had been held, and he hoped they’d eventually have ten times that number (the article itself notes that “[a] number of members were afterwards enrolled”). Another speaker summed up the strength of the movement thus far this way:

Some good Nonconformists could not go so far as to passively resist, but at the present time 3,000 persons had been summoned, and there were 35,000 others waiting to be summoned.

The Chairman then noted “that fourteen ‘resisters’ would appear at Chesham on , and fifteen more were ready to step into the dock the following week.” The meeting passed a resolution condemning the Education Act (but no mention is made of the usual resolution that was paired with this: commending the passive resisters).

The Dover Express reprinted a manifesto issued by the Dover Passive Resistance or Citizens’ League in its issue, and noted that some members of the League had appeared in court to respond to their summonses. The manifesto is largely a recapitulation of by-now-familiar grievances about the Act and doesn’t give much more information about the tax resistance campaign itself.

An interesting letter appeared in the Derby Daily Telegraph of :

Passive Resistance: ’s

Sale

To the editor of the Derby Daily Telegraph–

Sir,– Allow me to express my indignation at the way the sale was conducted at the County Hall.

Until I have always been opposed to, and never was in sympathy with, those who were reported to have been at the various sales and caused disturbances, but on attending this morning’s sale I was astonished at the un-English way the whole thing was arranged and carried out.

When we take into consideration that we are only human we cannot wonder at the voices of protest being raised.

If this sale is a sample of those which have been carried out in the past it appears to me that unless they are conducted by those in authority in a more business-like manner we may look for trouble ahead.

I feel I am now more than justified in placing myself side by side with the passive resisters.

Fair Play.

.

The Manchester Courier and Lancaster General Advertiser of covered the first set of passive resisters to be brought to court in Manchester. “Long before the hour for the commencement of the proceedings,” the report read, “the court was filled with male and female sympathisers, admission being gained by ticket.” The usual distraints were issued, and the usual protest meeting held thereafter.

The following article showed that someone was upping the ante:

Commitment Sought Against a Minister

William Swarbrick, assistant overseer of the Garstang Union, appeared before the Garstang justices on and applied for a commitment order against the Rev. J. Angell Jones, Congregational minister, Garstang.

A fortnight ago, Mr. Jones was summoned for non-payment of the education rate, and Mr. Swarbrick informed the Bench that when he visited Jones’s house on he was informed that he had no goods, all of which belonged to his wife.

After retiring the Bench adjourned the application until next court.

Additional brief articles told of “ladies who applauded [and] were removed from the court” at the trial of a Methodist minister, of nine resisters at Chester who were treated curtly by the court there, and of a pastor at Newton-le-Willows who was summoned for failure to pay the education rate.

The trial of another set of passive resisters from Manchester was covered in the Manchester Courier and Lancaster General Advertiser, though these were described as “the first which have come before the magistrates in the Manchester Division of the County” so I may be confused about the jurisdictional boundaries. In any case, “the court was filled with spectators.” One of the defendants slid in a suffragist point:

Mrs. Webster remarked that she desired simply to state two reasons for objecting to that rate.

In the first place she objected to pay for sectarian teaching, in which she did not believe, and secondly, as a woman, who had no Parliamentary vote allowed to her, she had no other means of publicly protesting against that act of injustice.

A public meeting was held thereafter, but being outdoors in the rain, was not well attended. A second article covered the distraints from those resisters from Manchester discussed in the earlier edition of the paper. The way in which the distraints went off gives us some clues about how the movement was preparing itself for this eventuality and trying to best react to it:

[T]he two officers drove in a cab first to the house of the Rev. C.W. Watkins… There was no demonstration; the officer quietly entered the house, and Mrs. Watkins offered them a gold watch and chain.

The inspector said he thought the watch would be sufficient to meet the claim, and departed with it.

The officers next drove to the house of the Rev. Dr. Leach… In the front garden there is a notice on a board to the following effect:– “The bailiff is going to take my goods because I will not pay rates for the teaching of Popery and Anglicanism.

— Chas. Leach.”

On their arrival at the house Dr. Leach asked the inspector for his authority, and the distress warrant was accordingly produced.

The rev. gentleman then asked the officer, “Do you, as a policeman, like this work?” but Mr. Clegg did not vouchsafe any reply.

Dr. Leach expressed his regret that any policeman should have to do such work, and then asked the officer to look round the room, remarking “You can tell those who sent you they can take every stick, but even then the rate won’t be paid.”

The officer, in reply to a further question, said that the claim was for about £1.

“Cannot you take me instead of the goods?” queried the rev. gentleman, and the inspector, with a smile, said that he could not.

The next question asked was, “Would you like something heavy or light?” and Mr. Clegg, naturally, replied that he would sooner have something that was light.

“Then,” said Dr. Leach, “you had better take my theology, for that is very light.”

The officers were eventually handed half a dozen solid silver serviette rings, and expressing themselves as quite satisfied, they departed for the next residence on the list.

There were only three or four persons assembled outside Dr. Leach’s house.

Subsequently Dr. Leach informed our representative that he was well pleased with the courtesy that had been shown by the officers, who had done their best to make the business as pleasant as possible.

Mr. Edwyn Holt’s residence, Appleby Lodge, Rusholme, was next visited, and the officers were cordially greeted and shown into the drawing-room.

After the usual questions, Mr. Holt said he intended to hand over his gold watch, and produced a case containing that article.

Mr. Holt then shook the officers by the hand, and remarked “I am as pleased to have seen you as if you had been the King, whose representatives you are.”

On arrival at Mr. R.D. Darbishire’s house in Victoria Park, the officers were shown into the dining-room.

Mr. Darbishire produced the silver casket containing the freedom of the city of Manchester presented to him by the Corporation in , and in handing it over to the officers he said that he was giving up the most precious possession he had.

(A note in the edition of the paper indicated that “a gentleman who does not wish his name to be disclosed redeemed the casket containing the freedom of the city which Mr. R.D. Darbishire handed to the police in satisfaction of the distress warrant…”)

A brief note further down the page notes that a sale of distrained goods at Warrington attracted “several thousand people… but the proceedings were quiet and orderly.… After the sale a meeting was held on the fair ground.”

Finally, from the Gloucester Citizen of :

Passive Resistance.

A Mayor Distrained On.

Twenty Wimbledon passive resisters had their goods sold at a Battersea auction-room on .

All the goods were “bought in” except those belonging to Mr. Peter Lawson, Mayor of Fulham, who insisted “on principle” that his goods should be sold outright.

Revolting Magistrates.

At Market Harborough on , 25 passive resisters appeared before the magistrates.

Mr. John Smeeton, who sat on the Bench, rose from his seat and stated that he declined to have anything to do with the administration of “the iniquitous Education Act.”

This action was loudly cheered by a large crowd in Court.

Distress warrants were ordered to issue.

Mr. Samuel Rathbone Edge, a justice of the peace for the county of Stafford, an income-tax commissioner, and a former member of Parliament for Newcastle-under-Lyme, was summoned at that town as a passive resister.

The usual order was made.

Offered His Wife.

The warrant officer of Penge went round on distraining on the goods of passive resisters.

A well-known Nonconformist, who owed 2s. 10d., offered his wife, but the warrant officer declined to “seize” the lady, remarking that he had one at home.

Bundled Out of Court.

Summoned at Maidenhead County Police-court on for non-payment of the education rate, Mr. Thorpe, Fifield, village missioner, protested against entering the prisoner’s dock, but finally submitted.

After the order for payment was made, Mr. Thorpe proceeded to address the magistrates on his conscientious objection.

He was told to desist, but continued his remarks until the Deputy Chief Constable ordered the police to eject him.

He was then seized by three or four officers, and forcibly turned out.

The East Berks Liberal agent was in Court, and called the police cowards, whereupon he was seized and bundled out as well.

A colporteur was threatened with similar summary punishment if he did not hold his tongue.

Police-Sergeant Charged with Assault.

At the Petty Sessions at Wiveliscombe on , Police-Sergeant Frederick Charles Woolley was charged with assaulting Edward John Thorne at Wiveliscombe Police-Court on .

On Mr. Thorne, who was for many years chairman of the local School Board, was summoned for non-payment of the poor rate as a passive resister, and he persisted in making a statement.

Thereupon, it was alleged, the police-sergeant put his hand upon Mr. Thorne’s arm and dragged him a step or two.

Complainant contended that defendant had no authority from the Bench to do this, but the presiding magistrate said he used the words, “Turn him out.”

The case was dismissed.

That takes us through .