Before Gandhi, before the women’s suffrage movement, the iconic example of tax resistance was that of the resisters to the Education Act — an example that Gandhi, the suffragists, and others would take inspiration from. This now-obscure campaign was a big deal a century ago. Thousands of British nonconformists refused to pay taxes that they believed would go towards religious education not of their liking.

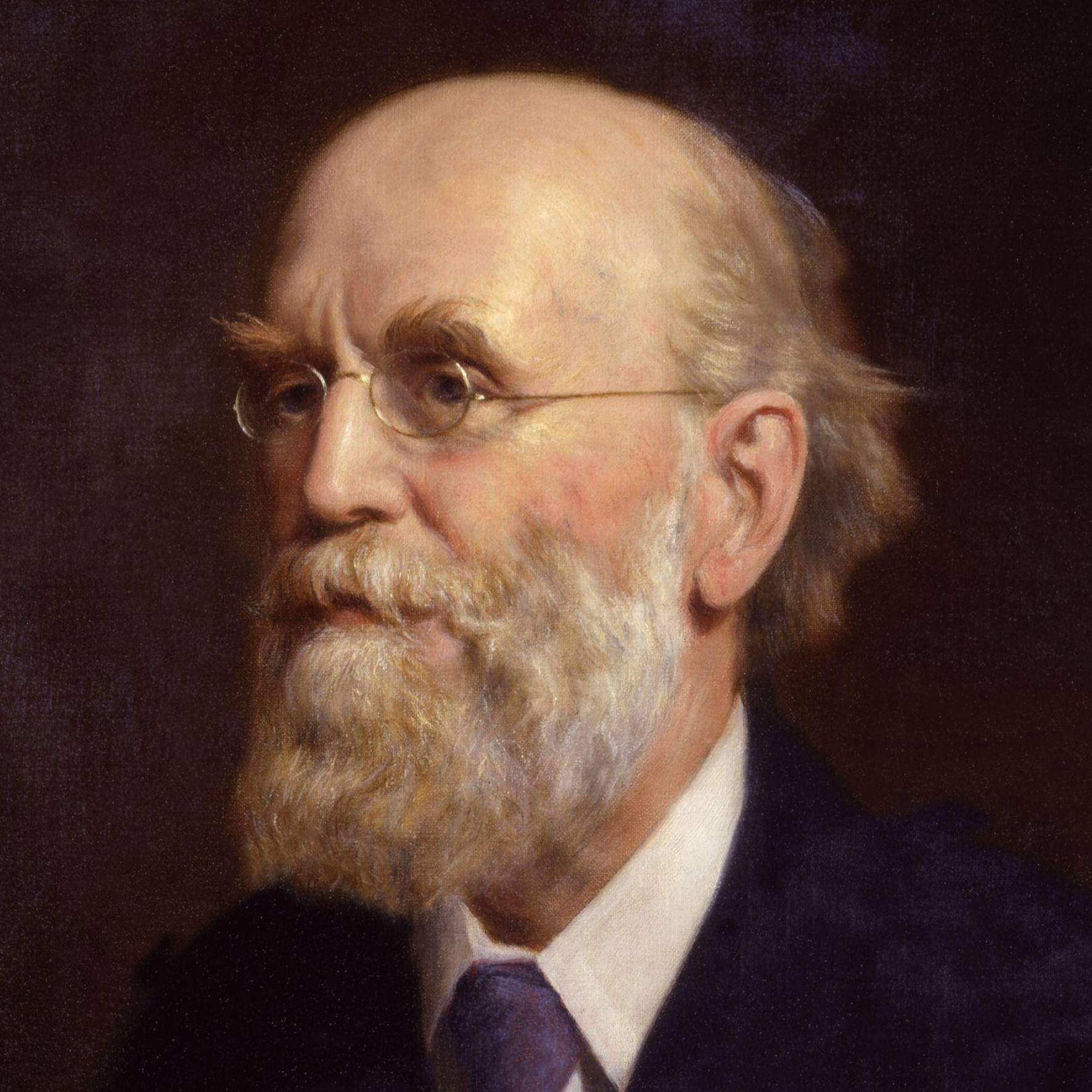

Today I’ll reproduce some news items from the earliest days of this movement. The first, from the Gloucester Citizen, introduces John Clifford who was to be the most prominent leader of the “passive resistance” movement:

The Education Act.

Policy of Passive Resistance.

Counsel’s Opinion.

Dr. Clifford, who is chairman of the National Passive Resistance Committee, has issued a letter to the 800 local councils of the National Free Church Council.

In this he states that the committee now formed will to some extent work independently of the Federation.

“As the Education Bill has become law,” says the doctor, “it is felt that no time should be lost in resorting to what is now our last line of defence; and, judging by the pronouncement of a very large number of the local councils in favor of passive resistance, we have thought it due to you to approach you direct.

It is hoped that a large proportion of the local councils may see their way to undertake passive resistance, but in districts where this is undesirable, it is strongly urged that passive resistance committees should be formed at once.”

Dr. Clifford appends the “opinion” of Mr. Edmund Robertson, K.C., with respect to the “passive resistance” policy.

The latter says:– “Regarding the position Nonconformists should take up, he would advise no man to break the law, but there was no breaking the law if they told the rate collector, ‘The law has given to the county council the power to enforce payment of these demands.

I am not going to volunteer payment of it.

I will leave you to collect it by the means which the law places at your disposal.’

There was nothing criminal in leaving the tax-collector and the rating authority to depend upon the resources which had been placed at their disposal.”

The next example comes from the Portsmouth Evening News. It sets out the grievances of the resistance campaign:

The Education Act.

A Plea for Passive Resistance.

[To the Editor of the “Evening News.”]

Sir,— The Borough and County Councils are now engaged in the work of preparing for the carrying out of the provisions of the Education Act recently passed by Parliament.

When the educational proposals of the Government were introduced, and during the discussion of them in the House of Commons, the great body of Nonconformists, and also a not inconsiderable number of Churchmen made strong and repeated protests, and denounced the Education Bill as being grossly unfair and unjust.

The feeling of hostility has not been removed or destroyed by the successful passing of the Bill.

It is quite true that Cardinal Vanghan has seen the triumph over Nonconformists which he so ardently desired; the clerical party have obtained more than even the late-Archbishop dared at one time to expect at the hands of the most friendly Government; and the Episcopacy has secured, by methods which even Churchmen have denounced as mean and unworthy, financial conditions of the most advantageous character.

But the end is not yet; and by large number of persons the Education Act will never be accepted as the outcome of a fair and just attempt to improve our system of national education.

The measure, recently passed into law, does not bear the sign and seal of popular approval.

As opportunities have arisen for testing the feelings of the electors, there has been condemnation, and in some cases of a most emphatic character.

The Act is not in the interests of the nation, but a sectarian education.

[Anglican] Churchmen and Roman Catholics have received ample consideration, while Nonconformists have been ignored and treated with contemptuous indifference.

In connection with the passing of the Education Bill, the country has received significant illustration of the sinister power and purpose of the priest.

The discussions which took place, especially in connection with the Kenyon-Slaney Clause, show that the priests utterly distrust the people, and claim to be free from control and supervision.

This distrust Lord Rosebery speaks of as being a most melancholy fact.

This Act has been not inaptly described as the “crowning of the priest.”

The sound principle that taxation and representation should go together is violated.

A gross injustice is perpetuated by the exclusion from the position of head masters of those who are honest and consistent enough to refuse to submit to religious tests.

There are some 16,410 places, in schools supported by rates and taxes, which are closed to Nonconformists.

No matter how intelligent or capable or religious they may be, they are barred from places which they could well fill, unless they can submit to tests which are called religious.

The financial provisions of the Act are in the interests, not of the children, but mainly of the Anglican party.

The Bishops have shown their skill in being able to make a good bargain, by means which shocked Churchmen like Mr. Middlemore, and which the man in the street would call sharp practice.

By the diversion of endowments belonging to the poor, by half fees, and income from rent, the Church has managed to do a profitable stroke of business for itself.

We have now what virtually a new endowment of the Anglican Church, and also payment for Roman Catholic teaching means of rates and taxes.

In many of the schools, managed by the clericals of the Church of England, we shall have an atmosphere and teaching well saturated with sacerdotalism.

I will give a sample of the mischievous and scandalous teaching to be met with in not a few quarters.

Quite recently clergyman when preaching, said: “They must accept Christ’s teaching only in the Holy Catholic Church.

To a good Christian they must be everything that the Holy Catholic Church teaches, because that Church was the sole authority appointed by Christ to teach His doctrine and carry on His work.”

We must, of course, put ourselves into the hands of the priests.

And now comes a choice utterance from this priest:— “If a child came for advice, saying its parents had told it to go to chapel, it was their duty, dreadful as it may seem, tell the child to disobey its parents and go to church.”

In many a parish, where there is but one school, a man of this type will have a chief power in appointing the teacher, in creating the school atmosphere, and in various ways poisoning the minds of the Nonconformist children who must attend his school.

And the Free Church taxpayers will be asked to pay for their children to taught disobedience to parents, and the awful sin of worshipping God in a chapel.

There are many Nonconformists who cannot possibly accept the Education Act or quietly and meekly submit its provisions.

We are told that what we are to do is to help in returning the Liberal Party to power in order to obtain redress.

If there be no new “khaki” cry it is probable that the Liberals will win the next election.

But if they become much more earnest and enthusiastic than at present, it is most improbable that their majority will exceed the Conservative and Irish parties who are one on this question.

But even if this were to realised, there remains the House of Lords, which knows little, and cares less, about the principles of Nonconformity.

The Education Act, which is in many respects unjust, and which invades the domain of conscience, must be met by passive resistance.

Nonconformity is being put to the test.

It will be a sorry day for Free Churchmen in certain places to sit at ease, wrapt a spirit of indifference and saying to one another, “The Act does not touch us very closely in our town, it may even lighten the rates, let there be peace.”

We need to saved from mere parochialism, and to think of those who are in places and positions of difficulty, who suffer injustice and wrong, and who experience even petty persecution because of their fidelity to Nonconformity.

That which is unjust is vulnerable.

And if as Free Churchmen we are true to our principles, if we act as well as talk, if the spirit of our fathers is alive to-day, we shall win in the struggle against injustice, and shall bring to naught the attempts of the clerical and obscurantist party.

I am, yours faithfully,

J[emima] Luke

.

The Hull Daily Mail reprinted a manifesto issued by the Hull Passive Resistance League in its issue. I won’t reproduce the parts of it that restate the basic grievances, which were well put by Jemima Luke’s letter. Here is the part of the manifesto that explains their passive resistance stand:

Had the Act simply opposed our wishes and ignored our opinions, our duty to accept it would have been clear.

It is because it invades the sacred realm of conscience, and conflicts with our sense of duty to God that we resist it.

No arbitrary majority in the House of Commons, no Act placed upon the Statute Book, can make a moral wrong right, no duty to our King, however loyal we desire to be, can possibly over-ride our solemn obligations to God.

We cannot submit.

“Here we stand, we can do no other.”

We cheerfully and readily pay all other rates, including the rate for schools of a non-sectarian character under public management.

We only decline to pay such amount as after careful inquiry we believe to be required for sectarian schools.

We shall not resist the local authorities in any measure they legally take to collect the balance of the rate, but we shall not aid them.

The distraining of our goods is their act.

We are only responsible for what we voluntarily pay.

This course when taken by the Welsh farmers with respect to the payment of tithes was declared by Mr Justice Wills at the Beaumaris Assizes to be perfectly justifiable.

At any rate it is the only way open to us.

We are further convinced that it is our duty as far as possible to protect and preserve inviolable the conscience and liberty of our fellows. Hence we join together for mutual support and encouragement.

We have no word to say against others who dislike the Act, but prefer another method of resisting it.

“Let every man be fully persuaded in his own mind.”

But all who are prepared to unite in this method of protest against one of the most unjust and reactionary measures of modern times; all who desire thus to preserve the honour and religious convictions of true citizens, and to protect their fatherland from the encroachments of legalised and subsidised Romanism, are invited to forward their names to any of the undersigned: Mr G.W. Flint, president of Passive Resistance League; the Rev R. Harrison and Mr. G.W.C. Armstrong, vice-presidents; Mr. E.B. Stephenson, treasurer; the Rev W. Bowell, secretary, 73, Linnæus-street; Mr H.R. Wasling, assistant secretary.

N.B.– The League is open to persons of both sexes, and includes (1) Ratepayers who declare their determination not to pay the rate for sectarian schools; (2) Non-ratepayers who are in sympathy with its objects.

The Lincolnshire Chronicle and the Northampton Mercury of reported:

Probably the first public authority to offer “passive resistance” to the Education Act is the Isle of Wight Board of Guardians, which has declined to tax the machinery of the Poor Law to raise what is described as a “denominational rate.”

The Isle of Wight County Council is thus confronted with a refusal on the part of the Guardians to comply with the precept for expenses connected with the administration of the new Education Act.

The next report comes from the Gloucester Citizen:

Cinderford.

Passive Resistance.

On a meeting, which, however, was not very well attended, was held in the Cinderford Baptist Sunday schoolroom, with the view to the furtherance of the passive resistance movement which has been started in the Forest.

The Rev. W.W. Wilks (Pastor of the Cinderford Baptist Church) presided, and addresses were delivered by Revs. Samuel Harry (Primitive Methodist Circuit Minister, Pillowell), J.W. Jacobs, and D.J. Perrott (Pastors of the Primitive Methodist and Baptist Churches respectively, Lydbrook).

At the conclusion of the meeting persons were invited to subscribe their names to the roll, but only a few did so.

A collection was taken to defray expenses and for the funds of the Forest of Dean Passive Resistance Citizens’ League.

The speakers received thanks on the motion of the chairman.

The Portsmouth Evening News features a letter from passive resister G. Roberts Hern of the Barnstaple Baptist Church. It takes the form of a rebuttal to one “Councillor Pink” who apparently had taken the position that the passive resisters ought to render unto Caesar. It showed that the resisters were ready to meet this argument with the usual Christian counterarguments for civil disobedience:

…I don’t think we are meant to preach submission to Governments when they encroach upon the realm of conscience and invade the sphere of spiritual relationship to God.

If so, then the early martyrs were wrong when they refused to pay homage to Cæsar instead of Christ.

The young maiden whom we see pictured so often was wrong when she refused to obey the “regularly constituted authority” which demanded that she should take a pinch of incense and cast it into the censer for Diana and forswear Christ.…

The Bristol Western Daily Press reported on ’s session of the annual district conference of the Bristol District United Methodist Free Churches, which included this:

Mr W.G. Howell moved a resolution condemning the Education Act of 1902, believing it to be subversive to the great principles of religious equality which the Nonconformists of the country held so dear, and pledging the meeting to resist the operations of the Act by all legitimate means.

Mr Bird seconded the motion, and said they were all justified in using every power at their command to render the Act inoperative.

The Rev. F.P. Dale said he should like to know whether the term “legitimate means” would include “passive resistance.”

The Chairman thought it did, because they would not break the law; they would simply refuse to pay the money demanded, and if some of their goods were taken and sold the tax would be paid.

At any rate, he thought the passive resistance movement was legitimate.

The motion was carried unanimously.

The Rev. W. Vivian then moved that every support should be given by the circuits to ministers desirous of joining the “passive resistance movement.”

This was seconded by Mr Dale and carried.

A letter dated in the Coventry Herald from William Ernest Blomfield, president of the Coventry Passive Resistance League, defends the passive resisters from a variety of charges against both the legitimacy of their grievance and of their chosen resistance tactic. It is remarkable for putting forward (among other things) a more secular defense of civil disobedience:

But granted [for the sake of argument] that we are law-breakers.

Well, Sir, there is no sin in disobedience to a bad law.

It may sometimes be a supreme duty.

Human progress is bound up with resistance to unjust laws.

This is the price with which our freedom and our privileges have been bought.

The fruits of passive resistance in Coventry have been good.

And English history furnishes us with honoured names of men who refused to obey human law that they might be loyal to a higher law.

The renowned Robert Hall puts the case in a nutshell: “When the commands of the civil authority interfere with that which we conscientiously believe to be the law of God, submission to the former is criminal.

We must obey God rather than man.

Rights and duties are correlatives.

A right to command necessarily implies the enforcing that which is right with respect to those to whom the duty of submission belongs.

Conscience has a higher authority than any ordinance made by man.”

If human law and conscience conflict, conscience must be put first.

Does the conflict arise here?

This is a question every man must answer for himself, and the answers of equally conscientious men will diverge.… This question belongs to the sacred realm where the soul has to make its decisions alone.

So far from dictating to any man I have never sought to bring my personal influence to bear upon a single individual.

I have made my decision and given my reasons for it.

If those reasons commend themselves to my friends they will follow me.

If not I do not blame them, if so be their decision is conscientious, for no man should take so serious a step save under a grave sense of responsibility.

Two more letters defending passive resistance appeared beside that one in the issue, along with this article:

The Guardians and Passive Resistance.

At the Coventry Guardians meeting on Mr. Best, in presenting the minutes of the Finance Committee, said that none of the members present at the meeting were prepared to sign a cheque for the payment of the county rate for the parishes of Holy Trinity and St. Michael’s Without.

(Rev. G. Bainton: “Hear, hear.”

Rev. A.T. Hallam: “Very good.”

Mr. W.J. Dalton: “Very bad.”)

The reasons of the objections were well known.

No doubt the county rate must be paid, but the members of the Finance Committee refused to sign it.

Rev. A.T. Hallam: Is this a case where we are to understand that the members of the Board are on the side of passive resistance?

The Rev. G. Bainston thought they ought to know for what the money was to be paid.

The Chairman said he took it the cheque would be signed in the ordinary way unless a resolution was passed to the contrary.

Mr. W.J. Dalton moved that the cheque be signed, and said the reason of the refusal to sign the cheque was owing to the absence of the more liberal members of the committee.

The members present were on the Passive Resistance League.

Mr. Graham seconded.

Mr. Halliwell said that Mr. Dalton as a rule found a mare’s nest.

The members of the Finance Committee present, as far as his knowledge went, were not representatives of the Passive Resistance League.

At the same time they had ideas of what was right and what was wrong, and they liked to exercise these ideas occasionally.

He held that the Board had no right to spend the money of the ratepayers of the city of Coventry unless they had some direct representatives in the management of these schools.

(Hear, hear.)

If they had to vote this sum of £35 odd twice a year they ought to have some control over the spending of the money.

He moved an amendment that the precept be paid with the exception of a 1¾d. in the £ for the Education Rate.

The Rev. G. Bainton having ascertained that the amendment meant that they would pay everything but the Education Rate, said he would second it.

No public money ought to go to private sectarian institutions.

This money was to be paid for strict private sectarian schools in this city, and it was public money which represented all classes.

Mr. Halliwell admitted there might be a legal liability to pay the cheque, but if they tendered the whole of it with the exception of the 1¾d. in the £, due to the Education Rate, it would be a way in which they could get out of their difficulty without considering that they were doing a wrong.

There was no question of sentimentality or fadism about it.

(Hear, hear.)

They were not the first body to do this, as it had been done in many parishes in Wales.

He contended that until the ratepayers had the control in the payment of this money they were not right in signing this cheque for the support of the schools.

The amendment was defeated by nine votes to seven.

Also in the same issue:

Passive Resistance.

Sir George Kekewich, speaking at Exeter on , said that the whole policy of the Government in reference to the Education Act had been antagonistic to Nonconformists.

What stood before them was a sectarian war such as had not prevailed in this country since the period of the Church rate.

They had many weapons with which they could fight the Act, and he thought, perhaps, the greatest and mightiest weapon was that of passive resistance.

A citizen’s league for passive resistance has been formed at Northampton.

The chairman and secretary of the local Church Council were respectively appointed president and secretary of the league, and a committee of twenty-four, including two ladies, was elected.

A manifesto addressed to the inhabitants of Cambridge, and signed by Professor Sims Woodhead, Mr. W[illiam].

Bond, J.P., Mr. T.R. Glover, M.A., Mr. A.I. Tillyard, M.A., the Rev. W.B. Selbie, &c., has been issued, in which the signatories state they will not pay the education rate.

A copy of what was probably the manifesto described above, with seven additional signatories to those named, is found in the Cambridge Independent Press. It sets out the grievance in brief, addresses some objections, indicates that the aggrieved had patiently tried to obey and to use democratic modes of persuasion to get the government to treat them fairly, and says that they have decided on passive resistance as a last resort.

A writer of a letter printed in the Cambridge Independent Press was impatient with the insistence of Nonconformist leaders that people only resist individually as their own consciences dictated — thinking a more organized, coordinated, and disciplined movement was in order:

Passive Resistance in Cambridge

[To the Editor of the Independent Press.]

…I cannot think that Nonconformity in Cambridge will allow Passive Resistance to be an unorganised, invertebrate thing, such as is suggested by your statement of the present situation. If the leaders will not move, it is time the rank and file moved the leaders. What good result can be accomplished by an army in which every soldier is told to do as he thinks best?

Whilst the country is ringing with the clarion cry, whilst the voice of conscience is loudly heard elsewhere, when the old standards of faith and principle are being unfurled by Free Churchmen in every quarter of the land, Cambridge is strangely silent. The revival of Church rates, the re-imposition of the Test Act, the betrayal of religious freedom and equality — do these rouse no righteous indignation in the hearts of Cambridge Nonconformists as a whole as well as in their consciences as individuals?

If the Education Act only affected individuals I could understand the desire to allow individuals to act as they deemed wisest. But it strikes a blow at Free Churchmen as a body, and therefore I say let us resist as a body.

The Education Act has dug a grave for Nonconformity, but the coffin has not yet arrived, and we have yet to see the name upon the plate, nor is there yet a corpse to inter. London on throbbed and thrilled with resistance, and I believe there will be such a shaking amongst the dry bones of Cambridge as will surprise those ready to officiate at the funeral of Dissent.

I hope that ere another week has passed a public meeting will be called to gather together those willing to enrol themselves in this movement to resist injustice and oppression.

The bogey of “conspiracy” has been raised. If it is right for me to do a thing by myself, it is right for you to join me in doing it. If it be held to be illegal, so much the better for us, and so much the worse for those who are trying to resurrect the priestcraft of byegone days.

Personally I would rather go to prison than have my furniture interfered with. But those who open the prison doors will need to enlarge their prisons, for you cannot imprison half the population for conscience sake in the twentieth century. ―Yours faithfully,

F.J.H.

Cambridge, .

Another letter in the same issue, from Albert H. Waters, also pressed for more widespread resistance and concluded: “all resisters must mutually support each other. A subscription should be opened for the purpose of paying a barrister to appear on behalf of the summoned, and there may be other expenses to provide for.”

This covers some of what I was able to find from the opening few months of a campaign that would continue for years and would lead to imprisonments and would greatly raise the profile of tax resistance as a nonviolent civil disobedience tactic.