Skipping ahead to in our chronological wander through the newspaper coverage of the “passive resistance” campaign against the Education Act, we come first to the Burnley Express in which we see that the authorities have decided to start raising the stakes for the resisters.

Colne Passive Resisters Disfranchised.

The Revising Barrister last evening, at Colne, gave another important decision relative to claims of five Passive Resisters who had been struck off the list through non-payment of the education portion of the poor rate.

The first applicant to be reinstated on the list was Mr. John Hartley, a manufacturer.

Mr. Little: You don’t propose to pay the rate?

Mr. Hartley: I don’t propose to pay the education voluntarily.

Mr. Little: I don’t quite understand why you ask me to put you on.

Mr. Hartley: Because they have struck me off on their own initiative, and notwithstanding the amount was recoverable.

They have not tried to obtain the money in a legal manner.

Mr. Little: I suppose they ought to have taken steps to distrain upon you?

Mr. Hartley: Yes.

Mr. Little: Assuming there was not enough to pay the amount, would you like to go to prison?

Mr. Hartley: I might say there is quite sufficient.

The Assistant Overseer informed the Revising Barrister that Mr. Hartley had been struck off because he had not paid the whole of the rate.

Here Mr. Little was informed all the cases were similar.

Little was not sympathetic to their arguments and allowed their names to be stricken from the voter rolls. This was pretty serious business, because the passive resisters were really hoping to use their clout to bring the Liberals into power at the next elections, and it might weaken the passive resistance movement if it became seen as an obstacle to their political ambitions.

The following excerpts come from the Cheltenham Chronicle. The version I found is difficult to read in parts, so some of the figures I quote may be a bit off:

Cheltenham Passive Resisters.

A Day of Demonstration.

Visit of Dr. J.

Clifford

Following close in the wake of the remarkable series of meetings in Cheltenham under the auspices of the National Union of Free Church Councils has come “Passive Resistance Day.”

Fortunately it has happened that the day selected for the sale of the goods distrained from the [lady?]

Cheltonians who refuse to pay rates in respect of sectarian education was that following the conclusion of the Free Church Council Convocation, and the opportunity for a demonstration upon a large scale was far too good to be lost.

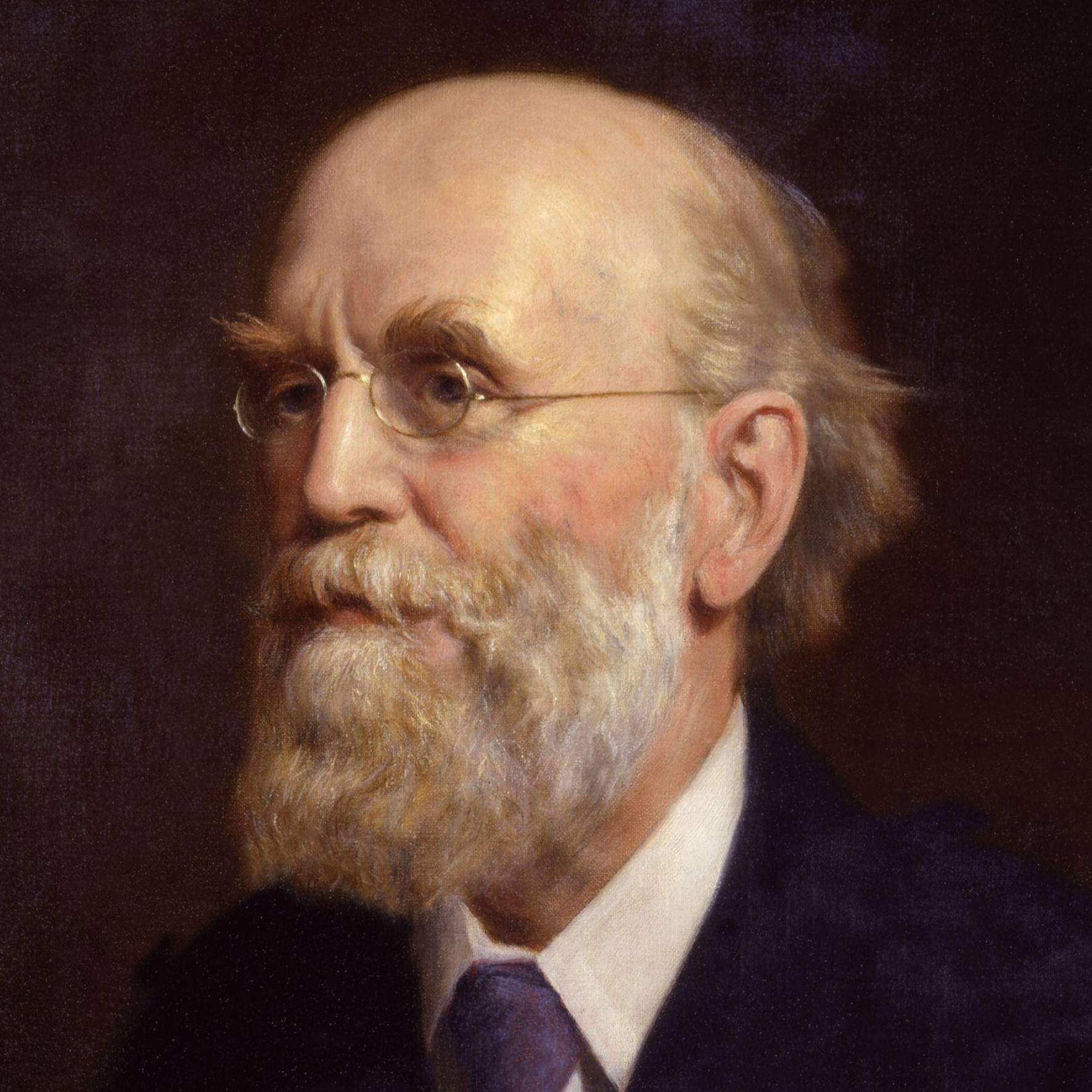

The services of the great champion of the passive resistance movement, Dr. John Clifford, M.A., were found to be available for the occasion, together with other prominent Free Church speakers, among the many officials and delegates remaining in the town for “demonstration day” being the Rev. Silas Hockins, and the Rev. Thomas Law (secretary of the National Federation of Free Church Councils).

Dr. Clifford presided at the opening gathering, which was held in the Town-hall at 11 a.m., under the presidency of Dr. Clifford, when the attendance numbered about [300?].

Mr. James Everett, the secretary, said they had gathered to hear the testimony of men who had suffered for conscience sake, and no doubt they would be glad to hear a few figures regarding the progress of the movement.

In spite of their detractors they were not a dwindling company — they continued to progress, and there were few [secessions?], and where one or two brothers and sisters had fallen away from their ranks they had had a large accession to their numbers.

Last week the largest number of summons issued during the whole history of the movement were heard.

Altogether 61,529 summonses had been issued, and there had been 2,097 sales.

There were 647 passive resistance leagues in existence, and 202 individuals had suffered imprisonment as follows: Once 99, 70 twice, 9 thrice, and four four times.

Of these [92?] ministers had been imprisoned 488 days, 109 laymen 759, and one lady 5 days, and Mr. Parker wrote to him last week and said he had just been committed for the fifth time (applause).

Theirs was not a political movement, but a deeply religious conscientious one, and whatever happened, although they had the assurance of the leaders of the Liberal party that the Education Act would be altered when they got the opportunity, they intended to keep on passively resisting until the Act was actually altered (applause).

Clifford spoke next, placing passive resistance in the Christian tradition of “obeying God and not men.” Later some individual resisters were heard from:

Mr. Everett read a letter from the Rev. W.J. Potter, of Stourbridge, who had served fourteen days in Worcester Gaol, apologising for inability to attend.

He expressed a fear that he would not be able to again go to gaol, as the overseers had joined his wife with him as occupier, so that they would distrain on her goods, which he had described as a cowardly and unchivalrous thing to do.

However, added Mr. Potter, they needed not to fear that she would pay (loud applause).

— Mr. Everett, however, pointed out that Mr. Potter need have no fear, for a learned counsel had given an opinion to the effect that it was illegal to make a wife joint occupier (applause).

Mr. W.H. Churchill, of Evesham, who had served 14 days in Worcester Gaol, was also unable to attend.

Mr. Everett said he was in gaol during one Christmas, bus since then his growing crops had been sold, for he was a market gardener by trade, a Quaker in religion, and a staunch and true supporter of their cause (loud applause).

This is the first example I’ve seen of a Quaker joining up with this nonconformist tax resistance campaign.

The Rev. S.J. Ford, of Minchinhampton, said he did not stand before them as an ex-prisoner.

His goods had been distrained on and sold, and twice he had been committed, but although he prepared to go to gaol his rate was paid on both occasions — once by a prominent Nonconformist — (shame) — not a member of his own church, for his people had pledged themselves not to interfere with his action in this matter, and the second time by an opponent who felt timid, or feared the reproach his imprisonment would bring upon them and their party.

He never intended to pay any rate or any portion of any rate until this iniquitous Act was for ever ended or mended (applause).

Mr. A. Farmer, of Coventry, who served 7, 14, and 7 days in Warwick Gaol, spoke with considerable feeling, but throughout his address there ran a pleasant humour which delighted the audience.

He said he did not feel like telling them of his experiences in gaol, because he thought they all ought to go and find out for themselves.

However, he told them something of the hardships to be suffered in “durance vile.”

Mr. J. Hodgkiss (Ledbury) has the misfortune to occupy in three parishes, and consequently to have three summonses every half-year.

He had had ten seizures of his goods and ten sales, which had cost him a little over £10 extra.

Altogether he had been fined for conscience sake to the extent of about £25, to say nothing of trouble and vexation, which had been more than money lost.

He had also lost his vote.

The last speaker was the Rev. A.R. Exard (of Dewsbury), who served seven days in Wakefield Gaol, and he produced a telegram received by him since he had been in Cheltenham, informing him that his name had been crossed off the voters’ list of his town.

It was a dastardly act, an abominable shame, but he was prepared to face it and to go to prison again, as he should have to.

He also quoted as another abominable “anachronism,” that, previous to the hearing of his case, one of the Bench of magistrates was heard to say “Give that little devil from Trinity a fortnight; it will do him good” (shame).

Concluding, the speaker said that he had made over all his furniture to his wife, who owned him also, but was willing periodically to part with him rather than the furniture (laughter).

An auction sale was held that afternoon:

Sale of Goods Under Distress.

Scene at the Victorial Rooms.

The sale of the “lares and penates” of the passivists captured in his recent raid by the gentlemen who executed the warrants issued at the local police-court had been advertised to take place at 3 p.m. At that time a company of about a hundred well-dressed and respectable-looking folk had gathered in the room… The fact that the auctioneer (Mr. Packer, of the firm of George Packer and Co.) was not able to be present before 3.30 o’clock left half an hour at the disposal of the company, and upon this the organisers had seized to continue the operation of “driving in the nail” which had been commenced in the morning, having persuaded Dr. Clifford and other gentlemen to come and speak.

From the applause which punctuated the speeches it was clear that the audience was an entirely sympathetic one, it consisting largely of the owners of the articles on the table and their friends, while a number of the delegates to the Free Church Council Convention who had remained in the town to hear the great D.D., and to see a sight which is now losing its novelty locally, were also present.…

In opening the speeches Mr. [Thomas] Whittard regretted that they had not a few hundred more passivists in every town; in which case those who had to do with the passing of the Act would have become ashamed of themselves, or if not ashamed at least obliged to use their strenuous efforts that it might be repealed.

Dr. Clifford read a telegram which stated that fifty Coventry resisters’ goods were sold by auction that morning, and added “Still keep fighting” (applause).… He had seen a gardener, receiving in wages 35s. a week, who deducted 9d. from his rate, but had to suffer quarter by quarter to the extent of 11s. The educational institution had got 9d. out of him, but in order that that 9d. might be stolen from him by the authority of the State, the man himself had to suffer to the extent of 11s. Yet people described their action as a cheap and easy martyrdom.…

The auctioneer (Mr. George Packer) having now arrived, was welcomed with a cheer, and commenced by apologising for having come so early, and thus intruding between them and so much pleasure.

He did not know what they considered the business of the afternoon, but he judged from the numbers before him as compared with last time he was there that it was not the selling of the goods (laughter).… An English concertina… was after a very brief bidding knocked down to Mr. Samuel Bubb, of Prestbury, and to the end the name of Mr. Bubb was heard at the conclusion of each series of biddings, the humour of the oft-repeated “Mr. Bubb” eventually resulting in a ripple of laughter after each mention of that persevering buyer’s name.

No time was wasted; instantly the article submitted reached the amount required, down went the hammer, and Mr. Bubb was declared the buyer.

In one case it was a valuable bicycle, which went for 7s. 10d., and the auctioneer could not in this instance refrain from complimenting Mr. Bubb on his bargain with the remark: “A cheap bicycle that, Mr. Bubb,” which little professional sally was followed with another little ripple of merriment.

Ultimately, the list having been exhausted, Mr. Packer congratulated his brother, who had executed the warrants, upon the caution with which he had made his levy, the prices realised showing that he had not taken a shillingsworth too much (more merriment).

A demonstration was also held that evening, attended by “some eighteen hundred people.”

The Chairman [Mr. C. Boardman, Justice of the Peace of London, formerly of Cheltenham]… supposed another reason for his selection was the fact that his name had come a little prominently before the passive resisters of the country in consequence of the action of the overseers of West Ham in taking a case into the Law Court, whereby the question of whether the stipendiary magistrate had a right to receive part payment of the rates from those who had refused to pay the “priest-rate” had been decided in favour of the stipendiary (applause).

The overseers still refused to take part payment; but the stipendiary as regularly ruled against them, and they had now to accept the part payment and get the balance in the way provided by the law (cheers).

F.B. Meyer spoke next:

“Don’t weaken,” continued the speaker, at the commencement of a very effective peroration. “Don’t pay your rates simply under protest. Protest is not good enough. The eyes of England are upon us. To fail now is to spoil the results of the sacrifices, tears, sorrows, and sufferings of the last two years. We must now fight this fight to a finish (loud cheers). The long red line of our troops has stood hour after hour in the thick of the cannonade. You may depend upon it that the time is coming when our general will say: ‘Up guards, and at ’em.’ Until that moment not one must flinch.…”

James Everett then spoke, giving somewhat different figures than in his earlier remarks: “155 men and one glorious woman had been imprisoned for periods varying from one to 31 days…” John Clifford spoke shortly after. His remarks were largely a revel in the traditions of nonconformity, a defense of their point of view on the Education Act, a Biblical defense of civil disobedience, and a denunciation of Romanist intrigue. No real details on the passive resistance campaign and its tactics, however.