Aristotle continues his list of important or essential characteristics of a state, and the nature of citizenship, in chapters ⅷ–ⅹ of book Ⅶ of the Politics.

A successful state will need, in addition to what has already been mentioned:

- a food supply

- a skilled workforce

- arms

- money

- religion, and a priesthood responsible for maintaining it

- a decision-making and adjudicating process

If you wanted to set up a new polis from scratch, for instance, you would want to make sure to bring some agriculturalists, craftspersons, warriors, wealthy people, priests, and judges along with you, so that, Gilligan’s Island-style, you’d have a full and diverse set of resources to draw on.

In the course of drawing up this list, Aristotle reminds us that saying something is essential to a state is not the same as saying something is part of the state. The state is an association of citizens; it requires a skilled workforce. That does not necessarily mean that the skilled workers are part of the state, that is, that they are citizens. The state may just sort of superintend the workers and use them as it fulfills its primary function, which is to contribute to the eudaimonia of the citizenry.

Aristotle takes a decidedly elitist tack in these chapters. Citizens, he says, should not be drawn from the working class or the petit bourgeoisie. Developing the virtues and participating in civic life demands a great deal of leisure time, which isn’t available to such people. Aristotle does not waste his breath speculating about the possibility of a classless society in which everybody’s eudaimonia matters.

On the other hand, as I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle himself was a perpetual non-citizen, yet he dedicated himself to a eudaimon life. Did he think that the best he could really hope for was a sort of second-rate eudaimonia of a political animal without political rights? I’ve been puzzling over that question while I’ve been reading the Politics but haven’t resolved it yet.

Aristotle suggests that, while still young, members of the ruling class should participate in the military. Then, when they grow older, they can leave the military for policy-making positions in government. This ensures that the force of arms is maintained by the ruling class, and also helps keep the military from feeling shut out from power and jealous of political offices (as its officers will eventually mature into such offices). When they in turn retire from state service, these elder statesmen may next enter religious service and attend to the less rigorous ritual practices of priestcraft.

The ruling class also needs wealth, Aristotle says. If they have to work for a living or otherwise scramble for money, they will not have time to attend to honing their characters and to matters of state. Indeed the land itself ought to be owned by the ruling class, though the cultivation of that land should not be their bother (that’s what slaves are for, or migrant labor). If you can arrange it so that each citizen owns a plot of land both in the city and in the outskirts, they’ll be less likely to divide into factions when the city is threatened from outside (for instance with those holding property closest to the front urging more desperate action and the townies adopting more of a wait-and-see approach).

Aristotle here also has praise for the practice of common meals that regularly bring the citizens together on an equal footing. He had mentioned this earlier as a feature of the Spartan constitution, and here he traces the origin of the practice to the Oenotrians of southern Italy and says that “it is universally agreed that this is a useful institution in a well-constructed state.” He says that it can be a financial hardship for those citizens who are less well-off (the meals were typically a sort of potluck, I believe, in which everyone was supposed to bring a dish sufficient to feed everyone at their table).

There should also, he says, be a certain amount of land held communally. Some of this will support common religious needs, but some might also be used to raise food for the communal meals so as to subsidize some of the poorer citizens.

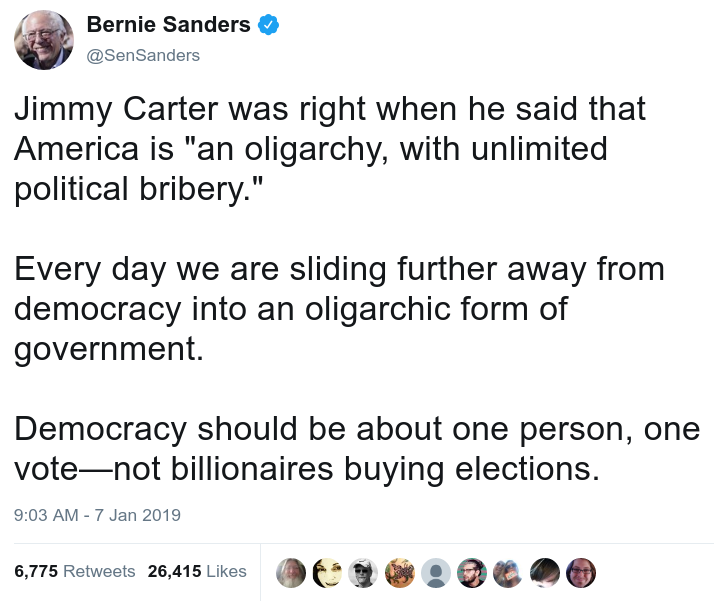

Debates about who ought to be part of the political process, concerns about the virtues of oligarchy and democracy, and demagogues flattering the populace in order to advance their power continue to be a central part of politics in today’s nation-states.

Index to Aristotle’s Politics

Aristotle’s Politics

- Introduction

- Book Ⅰ

- Book Ⅱ

- Book Ⅲ

- Book Ⅳ

- Book Ⅴ

- Book Ⅵ

- Book Ⅶ

- Book Ⅷ

- Alice Turtle’s Guide to Anarchism