After reading Hazel Barnes’s An Existentialist Ethics (see ’s The Picket Line), I got to thinking about the Trolley Problem and what an existentialist approach to it might be like.

In summary, the Trolley Problem is a thought experiment that you can use to investigate your ethical intuitions. The experiment is in the form of a story in which you play a part. In the story, a runaway trolley is headed towards a number of people who are for some reason on the tracks in its path and unable to get out of the way. You have an opportunity to stop or divert the trolley, but only at the cost of killing someone else. What do you do?

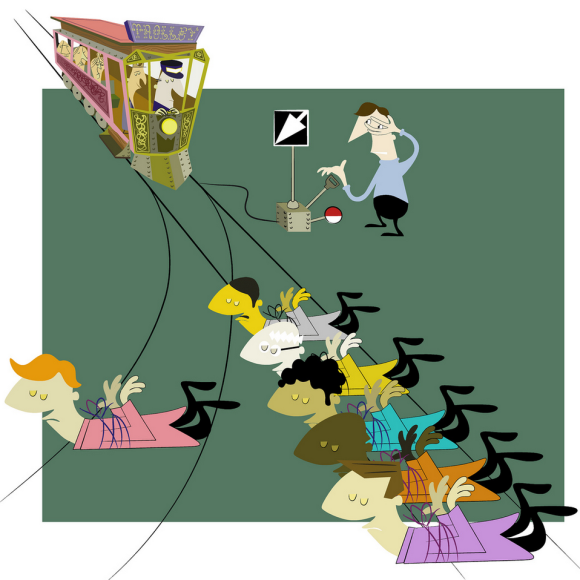

In the classic baseline trolley problem, you can divert the trolley onto another track, but there’s someone on that track who will be killed if you do:

The classic Trolley Problem (illustrations by John Holbo)

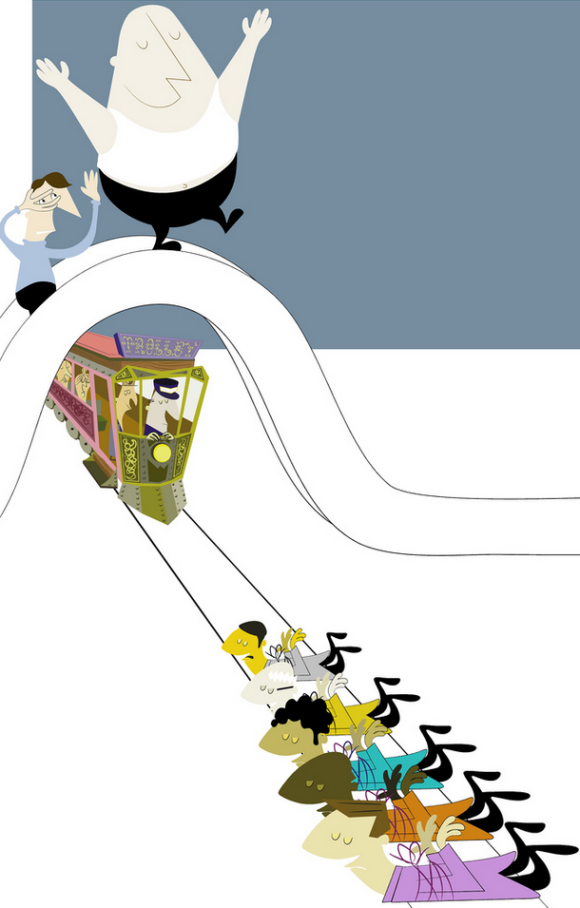

In a modified version of the Trolley Problem, you do not have a switch handy, but you and some poor schmuck are on a bridge overlooking the track, and the schmuck is just fat enough (and you aren’t) that if you were to push him off the bridge and into the path of the trolley this would stop the trolley before it hit the people further down the track… at the cost of killing the chubby schmuck:

The modified Trolley Problem

People tend to carry around with them a kind of unstable emulsion of utilitarianism and deontological ethics, and this problem has a way of throwing such people into a place where these two approaches have a tug of war: it is better for one to die than for five to die (utilitarian), but on the other hand people die in accidents all the time but it is positively bad for me to actively kill someone (deontological).

People who confidently answer “yes, I’d pull the switch” when presented with the first version, thinking that there’s nothing to it but a cold utilitarian calculation, will often balk at the second version of the problem, which from a utilitarian point of view seems identical.

Anyway, that’s the background. Now I’ll try to look at the problem through existentialist eyes.

An existentialist approach to a problem like this is not necessarily one that concludes in The Right Decision (do/don’t throw the switch / push chubby); it is more designed to keep you from going off the track and in making sure that you avoid the temptations to hide from your responsibility for making a decision.

In this point of view, the essence of Trolley Problem is that it puts you in a situation that will inevitably result in a bad outcome, but one you have the power to modify. You are entangled in this against your will and your inclinations, but once entangled there’s no getting out of it. You cannot decide not to be involved. There is soon going to be a bad outcome and you are going to be responsible (if not wholly responsible) for it. You have to own up to this and make a decision and accept the responsibility for the outcome.

Ze Trollee Problem, she ees a metaphor for life.

There are a bunch of ways to try to deny either the need to make a decision or the responsibility for the consequences, and the existentialist says that none of these are valid.

For example, you can try to draw a distinction between deciding to act (pull the switch, push chubby) and deciding not to act (stand there and do nothing) and claim that responsibility only attaches to the first sort of decisions and not to the second. How can I be responsible? I did nothing! The responsibility lies completely with the trolley company or the Hand of Fate. The existentialist says: bollocks.

(As an analogy: A friend of mine will soon be undergoing a severe round of chemotherapy to combat a dangerous cancer. He’s in for a very unpleasant time no matter what he does. When he is experiencing the worst of the chemotherapy, it will probably occur to him to think incredulously: “I chose to do this?” But he would be just as responsible for the results of choosing not to undergo chemotherapy even though he is in no way responsible for developing cancer in the first place. He would be making a bad decision if he were to decide based on whether the results of his decision might appear in this way to be more actively self-inflicted.)

Another evasion is to try to use some sort of rhetorical scalpel to remove the consequences of your decision from the decision itself. For example: when I pulled the switch, my intent was to divert the trolley from killing the five people further down the track, and the fact that the trolley then killed the one person on the other track was an unintended consequence of that act. So I’m only really responsible for the intended results of my action. More bollocks says the man in the beret.

It’s just as bad to try to foist the blame off on a philosophy — to say: it was not me who decided to pull the switch but utilitarian calculation; or to say: it was not me who decided not to push chubby but the Categorical Imperative. Similarly, appeals to The Law or God’s Will are out. Any claim that you have found the right moral answer inscribed on the fabric of the universe so that all you had to do was to read it off and obey its commands is an attempt to evade the responsibility for making the decision yourself and living with the results.

(This can be a problem with doctrinaire pacifism or ahimsa. It says that the right thing to do is always to do no violence or to do no harm, but life does not guarantee to always present you with choices where all of your alternatives are harmless or nonviolent. You may indeed have to choose between harms or between violences, and a doctrinaire pacifism or ahimsa is an invitation to come up with ways to wish away such choices in bad faith.)

Uncertainty can also be an evasion. You can try to come up with so many “what if”s that you feel justified in throwing up your hands and saying “there’s just no telling what the right decision is.” In real life, there’s no end to the uncertainty and the “what if”s, and they legitimately make decision making difficult and the results of our decisions hard to predict. But we have to be on guard against hunting for uncertainty as a way of trying to come up with an excuse for evading responsibility.

The way this shows up in the Trolley Problem is in people’s temptation to complicate it:

- How do we really know the fat man is fat enough to stop the train?

- What if the guy on the alternate track is a brilliant brain surgeon and the five people on the other track are a pack of scoundrels?

- What if I’m reading the switch incorrectly and it does the opposite from what I mean to do? I’m no expert on trainyard switchery!

- How do I know there aren’t ten more people further down the alternate track?

- What if the fat guy stops the train but there are people on the train who die in the collision?

- How do I know the five people on the tracks aren’t there because they want to die?

The hope is that if we can complicate the problem enough, then there will clearly be no right answer and so we won’t have to make any decision at all: we can look at the consequences of our indecision and say, “but for all we know, the alternative might have been even worse, so what can you do?”

(This one, to me, is the toughest nut to crack. If, in the face of uncertainty, you do some overt act that you reason has the best chance of having good results or averting bad ones and it ends up making things worse, you look like a fool or a jerk. Whereas if you fail to do some such overt act that may have made things better or less bad, and things just turn out to be worse as a result, the blame rarely falls on you. I think you’d have to be a very good existentialist indeed not to judge yourself in the same way.)

The problem with bad faith ethical reasoning is partially that it’s being dishonest with yourself and is a way of disengaging from life and from reality that is itself sad. But another problem is that it can distort your decision-making. If you think you can evade responsibility for choosing or for the results of your choice by making the choice conform in its structure to some bad-faith excuse (for instance, choosing inaction rather than action; choosing to obey the law because it is the law or to follow orders because they are orders; choosing what The Bible says; conforming to the will of the majority), you will be biased toward decisions that conform to such a structure rather than to good decisions (though sometimes they may coincide).