Colombia

Today I’ll try to convey what I heard about the state of Colombia at the conference. I’m no expert on the country or the region, my Spanish is iffy, and in such a short time I’m sure I only got an incomplete story, but here goes:

Militarism in Colombia

Colombians have been suffering from a long armed conflict featuring multiple guerrilla/paramilitary groups, the Colombian military, and private armed security forces. Colombia has the highest military spending in the region (by percentage of gross domestic product), and has a larger army than Brazil (which dwarfs Colombia in population and land area). And that doesn’t count the spending and personnel of non-government military actors.

This militarism has infected civil society by promoting the idea that security means superior force of arms, and by increasing armed violence in the cities in the form of street gangs and organized crime. In addition, the expansion of the military has come alongside a shrinking of social welfare spending as Colombia has adopted neoliberal policies, with the result that people now can most effectively get needed government benefits by joining the military (and this in turn has meant an increase in families with at least one member in the military, which tends to boost public support for militarist policies).

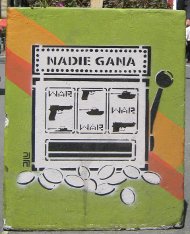

Colombian street artist Toxicomano (I think) decorated many of the planters along Bogotá’s Avenida Septima with antimilitarist messages: “The sound of weapons does not allow for listening to ideas,” “nobody wins,” “We don’t want to learn to kill!!”

Some parts of Colombia, including at least one entire department (state) are under martial law, with the civil government subordinated to military rulers sometimes to the extent of its near irrelevance.

The U.S. government sees Colombia as its regional partner in expanding its own military influence… something like a multi-level marketing scheme. Colombia has bases that function like the U.S. School of the Americas, where military figures from countries around the region and beyond come to get training from U.S. and Colombian forces on how to use the latest techniques and gadgets the military industrial complex is selling.

The expert speakers at the conference were by and large cynical about the ongoing peace talks between the government and the guerrilla group called FARC. This was for several reasons, such as:

- the talks do not include all of the armed factions fighting in Colombia (which means, among other things, that FARC, rather than dissolving or disarming, may just be absorbed by another faction)

- the talks do not address the social justice issues and in particular the war on drugs which fuel the conflict

- the talks do not involve representatives of Colombian society in general but only the belligerents and so are likely to result in a necessarily political resolution but one that evades political accountability or transparency

Some speakers emphasized that militarism has so degraded the ethics of society that nothing short of a grassroots revolution of cultural values will be sufficient to implement a real peace in Colombia. Former Colombian constitutional court justice and presidential candidate Carlos Gaviria Díaz addressed the conference and said that he feels “the central problem of Colombia is ethical character.”

Carlos Gaviria Díaz addresses the conference

Conscientious Objection in Colombia

The Constitutional Court of Colombia, the nation’s highest authority on the interpretation of the Colombian constitution (similar to the role of the U.S. Supreme Court in this regard) decided in that conscientious objection to military service is protected by the constitution.

However, the legislature has not implemented a law to govern the process draftees must follow to be designated conscientious objectors. The military also has not implemented its own process. Under the Colombian governmental establishment, the military and the courts are co-equal branches of government, so the courts cannot command the military to institute any particular process for dealing with conscientious objectors. The result of this “vacío jurídico” (legal vacuum) is that every objector who is drafted has to sue in court to be released, and must rely on the vicissitudes of individual, often hostile judges to win conscientious objector status.

In a future post, I’ll write about some of the efforts being made to improve this situation, and how conference participants helped in this campaign.

Press Gangs in Colombia

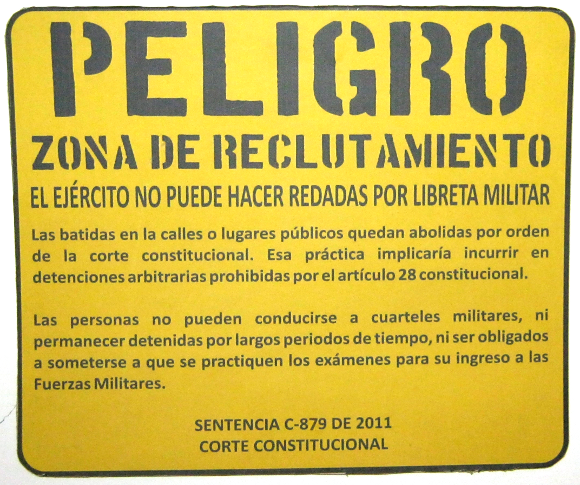

an anti-batida propaganda poster I saw at the ACOOC headquarters in Bogotá

There is an ongoing draft in Colombia that affects males of a certain age. There are grounds for exemption (being an only child, being disabled, etc.) but those who are exempted must pay a tax in lieu of military service. Upon serving, being exempted and paying your tax, or not being one of those selected in the draft, you are given a military ID card. You must carry this ID on your person at all times, and it is also required for things like getting a job in the above-ground economy, being granted a university degree, getting a passport, or owning property.

That said, this is a very leaky system: young men or their families can buy a card at a sliding scale (this is extralegal but commonplace), and one conscientious objector I heard about even traded a t-shirt for an ID card from a sympathetic official.

The military frequently conducts round-ups of military-aged men — swooping in quickly and detaining everybody, then taking anyone who does not have a card or whose card indicates that they have neither served nor been granted an exemption to the induction center to be immediately drafted. These round-ups are illegal but there seems to be no political will or power to stop them. These round-ups are called “batidas” in Colombia, and ACOOC says they have received reports of 45 different batidas from around the country in alone, and that the organization gets about 10–20 calls a day complaining about the practice.

Police sometimes collaborate with the military — seizing ID cards from young men and then turning them over to the military who induct them under the excuse that they were found without a card.

Offenses committed by members of the military in Colombia (such as, say, unlawful detentions like these) are by law prosecuted in military, never civil, courts. This means impunity in cases like these (and much worse cases — the military has done similar round-ups in the past called “false positives” in which it has massacred those it rounded up and then declared them to have been guerrillas in order to boost its body count).

ACOOC, working with War Resisters International, has created a standardized form that it and other groups working in this area can use to carefully document reports of batidas so that these reports will be maximally credible to the relevant human rights authorities.

A second campaign is trying to eliminate the requirement to have and carry a military ID card. This campaign is using a public awareness campaign, is lobbying universities to work to remove the ID requirement for graduation, and is also asking foreign companies with offices in Colombia not to require the IDs from those they hire.

Peace Communities

There are about a dozen “peace communities” in Colombia’s war zones that are trying to adopt and defend a policy of neutrality and grassroots demilitarization. I think I have heard that this has included refusing to pay war taxes to guerrilla/paramilitary groups. These communities are being assisted by International Fellowship of Reconciliation (IFOR) volunteer consultants and observers. Derek Brett, the IFOR’s UN representative (who has also worked there on behalf of Conscience & Peace Tax International), tells me that these communities have some of the highest casualty rates in the war. In one notorious case, one of the outspoken leaders of the movement was tortured and killed along with his family.