I started sharing my thoughts on Arne Johan Vetlesen’s Evil and Human Agency and I promised to continue as I worked my way through the book.

I’ve finished only one more chapter. When Vetlesen reviewed Hannah Arendt’s philosophical wrestling with evil, and Stanley Milgram’s sociological experiments, I was on at least somewhat familiar territory, as I’ve read some of this directly and have also read other authors who have wrestled with the ideas these two raised.

But in this latest chapter, Vetlesen describes some of the approaches to evil in psychology — is evil a part of human nature, or do people become evil (and if so, how)? Do people have a drive to do evil, or are their evil deeds secondary to some other motive? What about people who do not do evil: how did they develop that way, or how did they come to channel their drives differently?

And here, I’m out of my depth. I’m completely unfamiliar with most of the thinkers Vetlesen cites, and his summaries are too dense and require too much familiarity with the discipline for me to make much sense out of.

To me, many of the psychological theories he discusses strike me as just-so stories that either seem intuitive to you or don’t, but that don’t seem to have much else to go on. There’s lots of talk of existential despair, self and other, inner and outer, object and symbol, and things like “the autistic-contiguous position” and “projective identification.”

I can’t tell for sure whether I’m just being baffled by the jargon of a technical discipline that’s not my own, or whether I’m being snowed by the hair-splitting dogma of a pseudoscience. My rational mind rebels at reading about theories of developmental psychology that are long on new terminology and short on experimental data; or at discussions of motivations for evil that don’t acknowledge that the evolutionary psychology outlook even exists (or has produced a great deal of insight into this area: see Homicide for instance).

Vetlesen entertains several ideas about the psychology of evil, and also the idea that culture is (when it is working properly) a way to take the individual drives that lead to evil deeds and channel them instead into a symbolic realm where they don’t do any real damage. “Avoiding evil [says C. Fred Alford] ‘depends on the ability to symbolize dread’ ” — and this ability in turn relies on the cultural inventory of symbols and stories and such.

He also explores the idea that evil is rooted in envy, particularly envy of what is good in other people, and the resulting desire to destroy or defile that which is good. This makes evil more destructive than it would be if it were simply motivated by greed, for a greedy person would want to preserve the good thing (but keep it for himself), whereas an envious person is destructive of goodness itself.

Later, he returns to the case of Eichmann:

One of the questions Alford put to those he interviewed was: Was Eichmann evil? Much to Alford’s surprise, …nearly everybody asked to reflect on the question identified with Eichmann. … Likewise, there was a deep reluctance to make — or accept — any attempt to judge Eichmann’s actions from a moral point of view. In both groups [prisoners convicted of violent crimes and normals], the replies would take the following form: “Before we eventually judge Eichmann, we must bear in mind that he was acting within a hierarchical organization, receiving orders from his superiors; and surely he would have been killed if he had refused to do these things that others now call bad” (let me add: in fact, he would not). And then, to offer a final thought — actually, an angry counter-question — “Who among us can really be sure what we would have done in his place?”

Vetlesen wonders how people would look at the story of Eichmann and the millions of innocent people he helped to exterminate and identify with Eichmann. First, he asks if maybe it is “a kind of moral modesty” — hard to judge another unless you’ve walked in his shoes, that sort of thing. Then he gets what I think is probably the right answer, which is that the question itself invites you to examine Eichmann and sympathize with him (if only hypothetically) while leaving his victims unimagined.

But Vetlesen reads more into this, and thinks that perhaps people have a motive to identify with the perpetrators and not the victims because they in a larger sense prefer to identify with perpetrators rather than victims. In other words, it’s all well and good to say that you prefer to be neither victim nor executioner, but if you come to a fork in the road and only have the two choices, if you’re like most folks, you’ll take the executioner turnoff.

I wonder if maybe something else is at work. I recently read a paper by Paul Slovic — “If I look at the mass I will never act”: Psychic numbing and genocide — in which he shows (using scientific studies, numbers, evidence, the sort of psychological studies I feel I can bite into) that people seem to have a decreasing sympathy for victims the more of them there are.

As Stalin’s apocryphal quote goes: “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.”

For example:

Fetherstonhaugh, Slovic, Johnson, and Friedrich () documented this potential for diminished sensitivity to the value of life — i.e., “psychophysical numbing” — by evaluating people’s willingness to fund various lifesaving medical treatments. In a study involving a hypothetical grant funding agency, respondents were asked to indicate the number of lives a medical research institute would have to save to merit receipt of a $10 million grant. Nearly two-thirds of the respondents raised their minimum benefit requirements to warrant funding when there was a larger at-risk population, with a median value of 9,000 lives needing to be saved when 15,000 were at risk, compared to a median of 100,000 lives needing to be saved out of 290,000 at risk. By implication, respondents saw saving 9,000 lives in the “smaller” population as more valuable than saving ten times as many lives in the largest.

Here’s another:

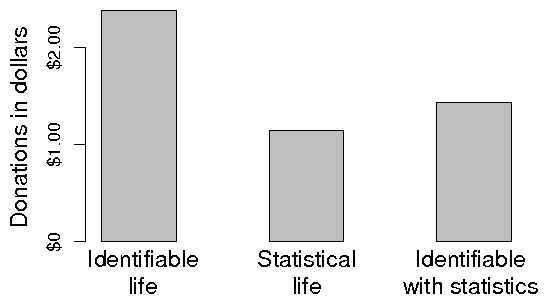

Small, Loewenstein, and Slovic () gave people leaving a psychological experiment the opportunity to contribute up to $5 of their earnings to Save the Children. The study consisted of three separate conditions: (1) identifiable victim, (2) statistical victims, and (3) identifiable victim with statistical information.… Participants in each condition were told that “any money donated will go toward relieving the severe food crisis in Southern Africa and Ethiopia.” The donations in fact went to Save the Children, but they were earmarked specifically for Rokia [the identifiable victim] in Conditions 1 and 3 and not specifically earmarked in Condition 2. The average donations are presented in Figure 8. Donations in response to the identified individual, Rokia, were far greater than donations in response to the statistical portrayal of the food crisis. Most important, however, and most discouraging, was the fact that coupling the statistical realities with Rokia’s story significantly reduced the contributions to Rokia. Alternatively, one could say that using Rokia’s story to “put a face behind the statistical problem” did not do much to increase donations (the difference between the mean donations of $1.43 and $1.14 was not statistically reliable).

Another study found that people were more likely to contribute toward a set amount of money that would be used for costly, life-saving medical treatment needed by a single child than they were to contribute toward the same amount of money needed for the same treatment of eight children.

Slovik’s conclusion: “[W]e cannot depend only upon our moral feelings to motivate us to take proper actions against genocide. That places the burden of response squarely upon the shoulders of moral argument and international law.” I don’t have much faith in international law, but I’m convinced by his arguments that empathy and moral feelings are inadequate guides to use when trying to decide on an appropriate attitude toward large-scale massacre or tragedy.