We may be tempted to petulance in our civil disobedience, conscientious objection, and even just our petitioning and protest, and I think we would be wise to be on guard against this temptation.

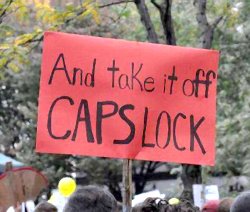

Petulance paints the relationship between the protester and the target of the protest as like that of an unruly child to a parent. Petulant tactics can take the form of making “demands” with nothing much to back them up but the demand itself. Or they can take the form of protest methods that seem taken from the playbook of a two-year-old — grown-up versions of “I’ll hold my breath until I die if you don’t give me what I want” or “I’m going to stomp my feet and scream if I don’t get my way.”

By taking the form of a tantrum, petulant protests increase bystander sympathy for the parentish figure and reduce sympathy for the childish figure, while at the same time reinforcing the idea that the parentish figure ought naturally to be making the decisions. In other words, petulant tactics bolster the authority of the target of the protest.

Wise parents do not give in to temper tantrums, and similarly, targets of petulant protests appear wise and sympathetic when they do not give in or when they defuse the protest by conciliating in token and condescending ways. This makes it less likely that the goals of the protesters (to the extent that they depend on action by the protest target) will be met.

Petulance is not an act of assertiveness, but a symptom of submissiveness. Petulant tactics can reinforce protesters’ feelings of inferiority and powerlessness, and thereby discourage them from taking the necessary bold, confident, and effective steps to create change. Inferior and powerless people whine, make toothless demands, and throw tantrums. Equal and confident people look each other in the eye, state their cases calmly and forthrightly, and do what they feel they have to do without making a big hullabaloo. Petulant protesters, by reinforcing the feelings of social superiority in their targets, can make those targets less inclined to negotiate or to listen.*

Defenders of petulant protest tactics might argue that because their targets are not like wise parents at all, but like foolish ones, petulant tactics are best since in such cases the squeaky wheel gets the grease. Also, some protesters may be forced into positions of powerless inferiority and then have no recourse but to use petulant tactics that are appropriate to such a position — for instance, the Irish prisoners who used tactics like hunger strikes or smearing the walls of their cells with feces.

But even if there are situations in which petulant tactics are called for, I think such tactics are frequently used, especially today, at times and in ways that are counterproductive. In many such cases, switching to tactics that are dignified and that assert the social and ethical equality of the protesters and the protest target would be more effective — both at winning the immediate goals of the protesters and (what ought to be among the long-term goals of anyone working for a better world) at fostering more healthy relationships among people and between people and institutions.

For example, the lunch counter sit-ins during the American civil rights movement were done in a dignified way: polite, well-disciplined black Americans sat at “whites-only” lunch counters, and stayed there in patient expectation of being treated in a reciprocally dignified manner although they were refused service. If they had chosen a petulant mode of protest, they might have then begun chanting, or yelling at the staff, or maybe vandalizing the lunch counters. Instead, they stuck with the quiet dignity approach, and let the white racists monopolize the petulant tactics (violence, verbal abuse, spitting on or pouring catsup over the protesters, that sort of thing). The dignified mode arguably was a more effective tactic for ending lunch counter segregation (the immediate goal of the protests), but was certainly a more effective strategy for discrediting racism and Jim Crow and in increasing sympathy for the civil rights movement.

This example is more cut-and-dried than most, since the battle against Jim Crow was so centered on asserting dignity and equality — but I think most other individual and grassroots political actions would also benefit from transcending the petulant and taking a forthright, dignified, confident posture.

How do we defend ourselves against this temptation to use the petulant mode at times when it is unnecessary and counter-productive?

First, acknowledge that the temptation exists, and that it springs from internalized feelings of social and ethical inferiority with respect to the protest target. We go into petulant mode for much the same reason a child does — because we despair of being listened to or heeded any other way and we are too powerless, inarticulate, or uncreative to use more effective methods of meeting our goals.

Second, make an effort to examine protest tactics that we come across or that are proposed to us with an eye to discerning to what extent they use the petulant mode. Share your observations with others; compare notes. Evaluate protests not only in terms of how they might meet immediate goals but in what impressions they create or reinforce about the relationship between the protesters, the protest targets, and bystanders.

Third, reimagine our relationships with the targets of our protests in such a way as to suspend or dispel the internalized feeling of inferiority. If you felt yourself to be the social and ethical equal of the people who are the target of your protest (as you perhaps already consider yourself to be, on a rational level), how would you convey your protest to them and how would you expect them to respond?

Fourth, know that petulance is usually meant to intensify or amplify a protest that feels too small, unnoticed, or insufficient. When you feel the petulant temptation, see if maybe you can amplify your protest in some other fashion. If not, consider that maybe a quiet, dignified, under-the-radar protest might nonetheless be more effective in the long run than a loud, annoying, attention-getting, petulant one.

Fifth, be honest with yourself and others about what you are doing and what goals you can reasonably expect to accomplish. Petulant protest often is accompanied with bluster and exaggeration, which can lead to discouragement when reality sets in.

By taking care in this way, we can increase the effectiveness of our actions, reduce the risk of discouragement and burnout, become more appealing and convincing to potential sympathizers, and contribute to a better world in the long run.

* Gandhi, on this point, counseled: “Non-cooperation is not a movement of brag, bluster, or bluff. It is a test of our sincerity. It requires solid and silent self-sacrifice. It challenges our honesty and our capacity for national work. It is a movement that aims at translating ideas into action… ¶ A non-cooperationist strives to compel attention and to set an example not by his violence but by his unobtrusive humility. He allows his solid action to speak for his creed. His strength lies in his reliance upon the correctness of his position. And the conviction of it grows most in his opponent when he least interposes his speech between his action and his opponent. Speech, especially when it is haughty, betrays want of confidence and it makes one’s opponent skeptical about the reality of the act itself.”

When I originally wrote up these observations, I used Gandhi’s hunger strikes as an example of a variety of petulant protest that may have been an effective one. After reviewing some of what Gandhi wrote about the tactic, though, I’m not sure it qualifies. When he was on hunger strikes, he often compared himself to a parent, and those he was trying to influence to children. He viewed hunger strikes (sometimes, anyway) as a form of penance he would undertake because he had failed to discipline his (metaphorical) children well; the “children” would then, because of their esteem for him, repent and get straight (at least if the strike worked as planned). This is a little odd, and bears some resemblance to the petulant mode I’m trying to describe, but isn’t quite the same.