Here’s a special Picket Line treat: the complete text of William Davis’s The Fries Rebellion, lovingly reformatted in semantic HTML.

The Fries Rebellion is the third of three internal rebellions that troubled the fledgeling United States government in the late 18th Century (the other two being Shays’ Rebellion and the Whiskey Rebellion).

The way Davis tells the story (though I think there’s reason to read between the lines rather than just absorb his take on it), the Fries rebellion was just a screw up all around. The rebels didn’t really understand the tax they were rebelling against, and so took up arms on the basis of wild, unfounded rumors. Once they figured out what was really going on, they settled down and were content — but then the federal government overreacted and sent in troops in a deliberate terror campaign that ended up making matters worse.

The rebellion takes place in a context where a British-leaning, conservative Federalist party, with John Adams as president, is worried about a possible war with France, and has decided to raise taxes to support increased military spending just in case. It has also cracked down on dissent, for instance with the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Why was the United States battling France, who had been our ally in the Revolution not many years before? Well, in between times, France had its own revolution. The United States took advantage of this to repudiate its debt to the French government (we don’t owe you the money, we owed the money to that guy there with the missing head). We also were playing let’s-make-up with Britain, which also pissed France off.

The American opposition party, the Democratic-Republicans, was more liberal, more democratic, and more sympathetic to the French and to their revolution.

The Federalists looked at the Fries Rebellion as a possible American revolt of the sans-culottes that threatened the government (and the urban elites the Federalists represented). The Democratic-Republicans saw Adams and his party as betraying the revolution and the cause of liberty with their quasi-royalist sympathies and their authoritarianism.

Fries and his crew kind of got caught in the middle, though they were not unaware of the larger political context. You’ll see in the story below that the Fries Rebels sometimes wore the French tricolor. Political loyalties made all the difference in determining how various people in the saga viewed what was going on.

In the end, the rebels were crushed. Perhaps it’s more accurate to say that they were rounded up, since they’d pretty much stopped rebelling by the time the federal government took action. But the episode helped cement Adams’s reputation as a power-mad, anti-liberty royalist. Adams lost to the Democratic-Republican Jefferson in the next election, and the Federalist party never won the presidency again. The government also never attempted a direct tax of this sort again.

Davis relies a lot on official accounts, which means we learn a lot more about the motives and tactics and statements of the government than about those of the rebels. You’ll note in this account a few details about rebel tactics, including harassment of tax assessors, refusal to take government posts, refusal to vote for offices that they find inherently illegitimate, and draft resistance.

The Federalists seemed to have two major goals: 1) utterly crush the rebellion and terrorize its potential supporters to the extent that nobody will try anything like this again, and 2) try to pin the rebellion on the Democratic-Republicans, if possible, in league with the French.

In the service of goal #1, they sent troops into a region that was already pacific as if it were a warzone, sweeping through homes looking for suspects, detaining people based on the anonymous denunciations of vengeful neighbors, on at least one occasion seizing, stripping, and whipping the editor of a Democratic-Republican newspaper, and marching lines of prisoners away in irons. Before this, they softened up the battlezone with a propaganda campaign that tried to explain how fair the tax was, largely on the basis of it being progressive (increasing at an increasing rate based on property value), and how important it was for everyone to obey their legitimate, fair, democratic government (for this, they enlisted a Philadelphia clergyman who sic’d Romans 13 on them), and how everyone will be treated with gentle care if only they surrender peacefully.

Fries himself had by this time given up being a rebel leader and gone back to his day job as an auctioneer. He was interrupted mid-auction, arrested, dragged off to Federal Court (his lawyers resigned in protest of Judicial railroading, so he was eventually left to defend himself), charged with treason (the indictment said that Fries had been “moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil”), convicted, and sentenced to be hanged.

President Adams eventually issued a blanket pardon for all of the Fries Rebels, but this didn’t seem to help his reputation any. He and his party went down hard. In the next administration, the Supreme Court justice who presided over Fries’s conviction was impeached for the way he conducted the trial!

The Fries Rebellion

An armed resistance to the house tax law, passed by Congress, , in Bucks and Northampton Counties, Pennsylvania.

W. W. H. Davis, A.M.

Author of “El Gringo, or New Mexico and Her People;” “History of the 104th Pennsylvania Regiment;” “Life of General John Lacey;” “History of the Hart Family;” “The Spanish Conquest of New Mexico;” “The History of Bucks County, PA;” “Life of John Davis;” and “History of the Doylestown Guards.”

Doylestown, PA. .

- Dedication

- Preface

- Ⅰ.

- Cause of Rebellion, John Fries

- Ⅱ.

- Insurgents Prepare to Resist the Law

- Ⅲ.

- Fries Captures the Assessors

- Ⅳ.

- Opposition to House Tax Law in Northampton

- Ⅴ.

- The Marshal Makes Arrests in Northampton

- Ⅵ.

- Rescue of the Prisoners at Bethlehem

- Ⅶ.

- The President Issues his Proclamation

- Ⅷ.

- Troops Called Out to Suppress the Insurrection

- Ⅸ.

- Rev. Charles Henry Helmuth Issues an Address

- Ⅹ.

- The Army Marches from Quakertown to Allentown and Returns to Philadelphia via Reading

- Ⅺ.

- Trial of John Fries

- Ⅻ.

- Pardon of Fries

- ⅩⅢ.

- Conclusion

- Appendix

Dedication

This Volume is Dedicated to the Students of History.

Preface

In presenting this volume to the public, it seems meet and proper the circumstances, under which it was written and published, should be stated.

I purchased the Doylestown (Pa.) Democrat , and, being interested in local history, began collecting the facts, relating to the armed resistance to the house-tax law of , and writing it up for my paper. I had heard a good deal of it in my youth and was curious to know more. It had its birth in Milford township, Bucks county, Pa.; thence extending into the adjoining townships of Northampton, and, in unwritten history, was known as the “Milford Rebellion.” There is no evidence that the people of Montgomery county had any part in it.

I visited the locality where Fries and his “insurgents,” as they were called, operated; interviewed his son Daniel, his only surviving child, then an old man of over 70, and others who lived in that section at the time of the trouble, hunted up all the known records and examined the newspaper files of the period. By the winter of I had collected considerable material and published portions of it in my newspaper. Since then additional matter has been added to the text, and many new facts, pertinent to the subject, are embodied in foot notes.

Being satisfied the facts, relating to this interesting episode, would have been lost, had they not been collected when they were; and believing them of sufficient interest to be preserved in some more enduring way, then attaches to the columns of a weekly newspaper, I determined to publish them in book form. The manuscript was prepared for the press several years ago, but the publication was deferred, from time to time until the present, and it is now given to the public with some misgivings. The events narrated are not only interesting in themselves, but too suggestive of the friction between the people and their newly established government, to allow them to become lost to the student of history. I have several friends to thank, including Messrs. John W. Jordan,* Charles Broadhead, Bethlehem, and Ellwood Roberts, Norristown, in the matter of furnishing illustrations for the volume.

W. W. H. DAVIS. Doylestown, Pa., .

* Pennsylvania Historical Society.

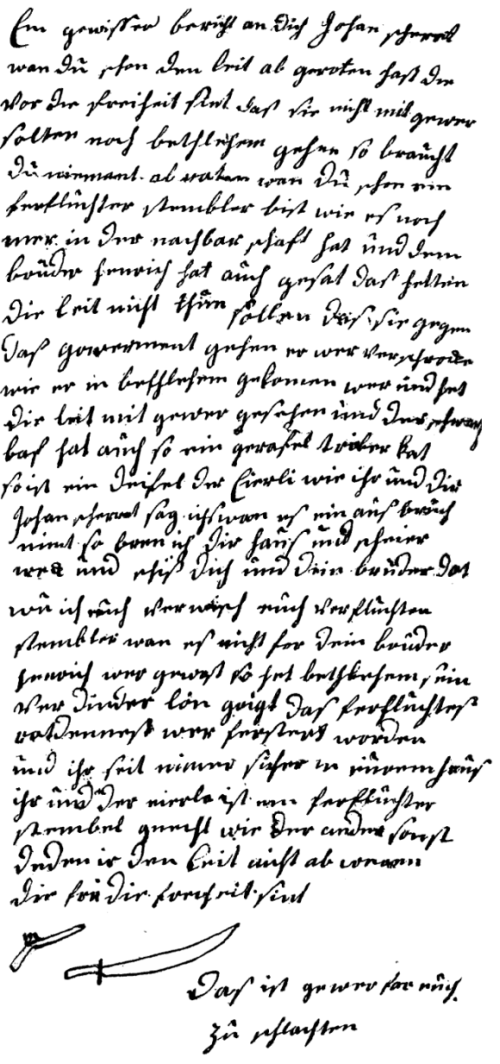

Threatening Letter

The following is a translation of the threatening letter facing page 12, sent, by an insurgent, to Captain Jarrett and is one of the earliest exhibitions of Kukluxism extant:

A sure warning (certain report) to you John Sheret if you have already advised the people who are for liberty that they should not go armed to Bethlehem, you need not discourage others any more as you are already a cursed stambler as are many others in this neighborhood. Your brother Henry also said that the people should not have done that to go against the government. He was scared when he came to Bethlehem and saw the people with weapons. (A line of the original here cannot be translated.) So Earl* is a devil as you and John Sheret. I say in case of an outbreak I will burn your house and barn and will shoot you and your brother dead wherever I shall detect you cursed stamblers. If it would not be for your brother Henry most surely Bethlehem would receive its deserving reward. The cursed advice would be frustrated. And you are never safe in your house. You and Earl* are cursed stambles knaves one as the other else you would not dissuade the people who are for liberty.

These are the weapons for your slaughter.

* Eyerley.

Ⅰ. Cause of the Rebellion; John Fries.

Between the close of the Revolution and the end of the Century, three events transpired in the United States that gave serious alarm to the friends of republican institutions.

The first of these, known in history as “Shays’ Rebellion,” was an unlawful combination in Massachusetts, , directed against the State Government. Its head and front was Daniel Shays,1 who had been a Captain in the Continental army, and left behind him the reputation of a brave and faithful officer. The outbreak was soon quelled, but not before some of the misguided participants had paid the penalty with their lives. The second event, in the order of time, was the “Whiskey Insurrection,”2 in the southwestern counties of Pennsylvania, . It reached such magnitude, by the fall of , that President Washington sent a large body of troops, under Governor Henry Lee,3 of Virginia, into the disaffected district. The force was so imposing the insurgents abandoned their organization and returned to their homes. The third attempt was that of which we write, the “Fries Rebellion.” This took place in contiguous parts of Bucks4 and Northampton counties, in the Fall and Winter of , and is so called from the name of the leader, John Fries, who was mainly instrumental in creating this opposition to the Federal authority. In each case the disturbance was caused in whole, or in part, by what the people considered an unjust and unlawful tax, and they resisted putting it in force. In the two latter cases the assessments to be made were of an unusual character, though not heavy in amount, and the opposition to it was caused, no doubt, by want of correct information, and not a settled design to interfere with the execution of the law. The history of the Fries Rebellion proves, quite conclusively, the outbreak was of this character, and, if proper means had been taken by the authorities to explain the law and its necessity, to the disaffected, the extreme measures taken by the general government need not have been resorted to. It was fortunate, however, the trouble was brought to a close without the loss of life or bloodshed, and the bitterness engendered was not permanent.

During the Administration of John Adams, the frequent depredations of the French upon our commerce, and their disregard of our rights on the high seas, as a neutral power to the sanguinary conflict then devastating Europe, induced the belief that war with France was unavoidable. Congress, accordingly, made preparation for such emergency should it arise. The military and naval forces of the country were increased, and General Washington, then living in retirement at Mount Vernon, was appointed to the command of the armies about to be called into the field. In view of the impending danger to the country, Congress took such other measures as the President thought requisite, some of which clothed him with almost despotic power. The act, known as the “Alien and Sedition Laws,” gave him authority to send obnoxious persons out of the country, at pleasure, and to place others in arrest accused of speaking, or writing, in disrespectful terms of the government. In connection with these measures Congress made provision to carry on the war, now thought to be near at hand, by laying a direct tax to be assessed and collected by agents appointed by the Federal government.

On , an act was passed providing “for the valuation of lands and dwelling houses and the enumeration of slaves within the United States.” For making the valuation and enumeration, required by the act, the States were divided into districts, and, for each district, a commissioner was appointed by the President with a fixed salary. It was made the duty of the commissioners to sub-divide these districts into assessment districts, and, for each, appoint one principal and as many assistants as might be required. The assessors were to make out a list of houses, lands and slaves, and afterward to value and assess them. On Congress passed an additional act, entitled “An Act to lay and collect a direct tax within the United States,” fixing the amount to be raised at $2,000,000, of which $237,177.72 was the portion allotted to Pennsylvania. The rates of assessments to be made under this act were as follows: Where the dwelling and outhouses, on a lot not exceeding two acres, were valued at more than $100 and not exceeding $500, there was to be assessed a sum equal to two-tenths of one per cent, on the valuation. As the houses and lands increased in value the rates were increased in proportion, so that a house, worth $30,000, would pay a tax equal to one per cent, of its value. By this means rich and poor alike contributed their share of the burden according to their ability to pay. Upon each slave there was assessed a tax of 50 cents. The fourth section of the act provided for the appointment of collectors, and the duties were to be discharged under instructions from the Secretary of the Treasury.

Upon the announcement of the passage of these acts of Congress, and their publication, discontent began to manifest itself. They were denounced as unconstitutional, unjust and oppressive, and the government charged with acting in a tyrannical manner. The odium already resting on Mr. Adams’ Administration was increased, and new enemies made on all sides. Politicians, who seized upon it to bring the Administration into disrepute, were governed by selfish purposes, but we must credit the masses with honest motives. Following so soon, after the passage of the Alien and Sedition Laws, gave the House Tax Law greater unpopularity than it really merited, or would have received at any other time. The feeling of the country was very much aroused before its passage, and this added fuel to the flame.

The law was violently denounced in Pennsylvania as soon as its provisions were known. At first the opposition took the form of noisy declamation, and the application of harsh epithets to the President and his Cabinet, and was mainly confined to the counties of Bucks, Montgomery, Northampton and Berks in the eastern part of the State. From passive resistance the opposition gradually assumed the shape of overt acts. In a few instances, and before any matured plan had been agreed upon, the officers were prevented by threats from making the assessments, and, in others, were hooted at and ridiculed. So odious did it make the Administration in Bucks and Northampton, that these counties positively refused to furnish their quota, under a law recently passed, for increasing the military force of the country, and not a man was furnished by them. The opposition had assumed such alarming character by the Winter and Spring of the President deemed it his duty to send a large body of troops into these counties to quell the disturbance and enforce the law. In order to give our readers an intelligent and accurate account of this outbreak, it will be necessary to take up the thread of events from the passage of the acts of Congress that led to it.

Immediately on the passage of the law, the Secretary of the Treasury took the proper steps to carry it out. The act of divided Pennsylvania into nine districts, the third being composed of the counties of Bucks and Montgomery, and the fifth of Northampton, Luzerne and Wayne, with the following named commissioners:

| 1st District | Israel Wheeler |

|---|---|

| 2d District | Paul Zantzenger |

| 3d District | Seth Chapman5 |

| 4th District | Collinson Reed |

| 5th District | Jacob Eyerley6 |

| 6th District | Michael Schmyser |

| 7th District | Thomas Grant, Jr. |

| 8th District | Samuel Davidson |

| 9th District | Isaac Jenkinson |

Jacob Eyerley, commissioner for the fifth district, and a resident of Northampton, was commissioned sometime in the month of August and took the oath of office. Almost as soon as qualified, he was requested, by the Secretary of the Treasury, to find suitable persons to serve as assessors in his division. He had no trouble as far as the counties of Luzerne and Wayne were concerned, but, in Northampton, only two persons were named in connection with the appointment. There appeared to be a general indisposition among the people to accept office under the law.

The fourth section of the act of required the commissioners, as soon as possible after their appointment, to meet and make provision for carrying out the act. The board assembled at Reading,7 Berks county, , nearly all the members present. Each commissioner presented a plan of his division and divided it into a suitable number of assessment districts. They also furnished a list of persons qualified for assessors, which was forwarded to the Secretary of the Treasury who was authorized to reduce the number. A form of warrant was agreed upon and signed by the commissioners. The assessors were ordered to meet at an early day, when the commissioners would qualify and give them the necessary instructions.

Bucks county was divided into two collection districts, one composed of the twelve upper townships, for which were appointed one principal and five assistants; James Chapman,8 Richland, being the principal, and John Rodrock,9 Plumstead; Everhard Foulke,10 Richland, Cephas Childs,11 Samuel Clark, Milford, and one other assistant. Childs took the oath of office , and no doubt the others were qualified about the same time. The assessors met at Rodrock’s the latter part of , after being qualified. Here the last preliminaries were arranged prior to making the attempt to carry the law into effect. Each assessor was given charge of two townships, and allowed a choice of the ones he would assess.

When it became known the assessments were actually to be made, and the tax collected under the “odious” law, the hostility of the people, which had somewhat abated since its passage, broke out anew in some localities. The excitement soon reached fever heat. The tax became the general subject of conversation throughout the country, and was discussed in the taverns, stores, at all public gatherings, and at every point where two or more persons came together. As is always the case in times of high excitement, the authors of the law were denounced in unmeasured terms, and both its object and provisions misrepresented. The most extravagant stories were put in circulation as to the intention of the government, and such a state of fear had seized upon the minds of the middle and lower classes, people were really alarmed for their personal safety. Many considered Mr. Adams a despot, and the act was viewed as the most oppressive that had ever disgraced a statute book. In this condition of things it is not in the least strange that a determination to resist the law should manifest itself. The opposition appears to have been more general in Milford12 township, in Bucks, and in some of the border townships of Northampton county, where the inhabitants early made open demonstration to resist the assessors. In Milford the officers were wholly unable to comply with the law, and there the houses remained unassessed for some time after the assessment had been made in other parts of the district. The most active man in stirring up opposition to the Federal authorities, and who, in fact, was the head and front of all the disturbance, was John Fries, Milford, who had the countenance and support of many of his neighbors and friends, of whom John Getman and Frederick Heany, after himself, were the boldest and most active participants in the rebellion.

It would be an easy matter, were we disposed to indulge in romance and present fictitious characters to the reader, to convert the leaders in this disturbance into heroes and clothe them with imaginary qualities; but, as we profess to deal only with facts, and intend to write a correct account of the outbreak, , such license is forbidden. Fries, Heany and Getman were plain, honest Germans only, and it is extending ordinary charity to suppose them to have been governed by sincere motives in the course they took.

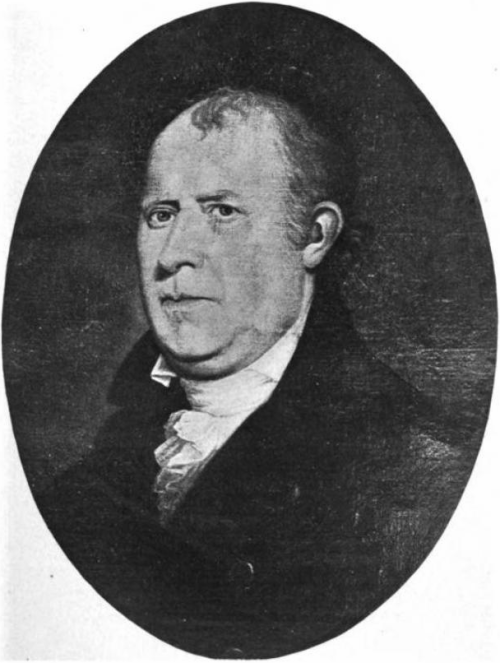

John Fries, the leading spirit of the insurrection and came of parentage in the lower walks of life, was born in Hatfield13 township, Montgomery county, about . At 20 he was married to Margaret Brunner, daughter of David Brunner, White Marsh,14 near Mather’s Mill.15 John was brought up to work, and, when old enough, was apprenticed to the coopering trade, which he learned. At twenty-five himself and wife, and their two children, removed to Bucks county settling in Milford township. We are not informed as to the exact locality, but were told by his son Daniel that Joseph Galloway16 gave him permission to build a house on his land at Boggy Creek, and occupy it as long as he wished, which offer he accepted. We have no means of knowing what length of time Fries lived there, nor when he changed his residence, but, at the time of the outbreak, we find him living in a small log house near the Sumneytown road, two miles from Charlestown,17 on a lot that belonged to William Edwards, father of Caleb Edwards,18 deceased, Quakertown.19 He probably did not follow the coopering business long, if at all, after his removal into Bucks county, for the earliest information we have of him shows he was then pursuing the calling of a vendue cryer [auctioneer], which he followed to the day of his death, and for which he seems to have been especially adapted. This occupation led him to travel all over his own, and neighboring townships, affording him an opportunity of becoming well acquainted with the country and the people. He had ten children: Solomon, John, Daniel, a second John, and a fifth which died in infancy before it had been named; Mary, Elizabeth, Sarah, Catharine and Margaret. Of these ten children Solomon and Daniel were the last to die, both aged men, who had already reached more than man’s allotted years. Daniel, the younger of the two, was born at “Boggy Creek,” .

When the contest between Great Britain and her American Colonies came on, , John Fries espoused the cause of his country, and became an active patriot. He was already enrolled in the militia and had command of a company. We are not able to say at what period he was first called into service, but we know he was on active duty , for, in the Fall of that year, his company being of the militia was called out from Bucks county to re-enforce the Continental Army, and was with Washington at White Marsh and Camp Hill.20 In the Spring of the following year he commanded a company in the action at Crooked Billet,21 under General John Lacey,22 and shared the dangers and defeat of the day. Nearly twenty years later, we find him in command of a company of militia, from this county, in the Whiskey Insurrection. In these military positions it is to be presumed he served his country faithfully.

At the period of which we write, Fries was about fifty years of age. In person rather small in stature and spare, but active, hardy and well made. He was without education, except being able to read and write, with a knowledge of the rudiments of arithmetic. Nature had endowed him with good natural abilities, and he possessed a shrewd and intelligent mind. He was an easy and fluent talker, and somewhat noted for his humour and cunning; was possessed of good hard sense, and, had his mind been properly cultivated, would doubtless have been a man of mark. Personally he was brave and resolute, and unknown to fear. He is said to have possessed a species of rude eloquence which was very engaging, and gave him great control over the multitude. He was a sworn enemy to all kinds of oppression, fancied or real, and was esteemed a quiet and inoffensive man until this outbreak aroused the latent fires within him, made him notorious and his name a terror to the Administration of Mr. Adams. He had brown hair, quick and steady black eyes, of which an old neighbor, and one who formerly knew him well, told us “were as keen as the eyes of a rabbit.” He had a pleasant disposition, was well liked by all, and, with many, quite a favorite. His character for honesty was above suspicion, and he was considered a sober man, though occasionally indulged in strong drink. These personal and other qualities gave him, to a considerable degree, the confidence of the community in which he lived, and enabled him to exercise a controlling influence over his neighbors and friends.

In following his occupation of vendue cryer he generally traversed the county on horseback, and, in all his wanderings, was accompanied by a small black dog named “Whiskey,” to which he was greatly attached. When he entered a house it was his habit to call for “Whiskey,” when the faithful little animal would come and take a seat by his side and remain until his master got up to go away. Master and dog were inseparable companions, and aged persons who knew Fries stated to us that his approach was often heralded some time before he came in sight by the appearance of “Whiskey” trotting along in advance. The favorite little dog, as will be seen, before we conclude, was the means of the betrayal of his master into the hands of his enemies.

Next to John Fries, Frederick Heaney and John Getman were the most active instigators of the disturbance. They were both residents of Milford township at the time, the former living two miles from Charlestown, the latter within half a mile of Fries’ house; they were tailors by trade, and in an humble condition in life. Of their history we have been able to learn but little. Heaney was born at what is now “Stover’s Mill,”23 Rockhill township, but we do not know at what period he changed his residence to Milford. At one time he kept the tavern at Hagersville,24 of which Christian Hager was landlord forty years ago, but we have not been able to learn the date of his residence at this place. After his pardon by Mr. Adams, Heaney returned to his home, Milford township, whence he removed to Plainfield,25 Northampton county, where he died.26 He gained there not only a respectable, but a somewhat influential standing in the community. He was appointed justice of the peace, and also commanded a volunteer company, which his grandson, George Heaney, commanded, . After his death, which did not take place until he had reached a green old age, his widow was twice married, and died in Plainfield, , at the age of eighty-nine years. He had three sons, Charles, Samuel and Enoch, and one daughter, Elizabeth. It is related by his descendants that while the troops were in pursuit of him, a party of soldiers came to his house one night, when his wife was alone, except her little daughter, Elizabeth. They heard of threats against his life, and, hearing them coming, she jumped out of bed and put a spike over the door to prevent them getting in, and, leaving her child in the house, ran out the back door and across the fields to alarm a neighbor. When she returned with help the soldiers were gone. This child was Mrs. Edmonds, living, , in Bushkill township, Northampton county, whose son, Jacob B. Edmonds, resided at Quakertown.

Getman is supposed to have been born in Rockhill township, also, but we have not been able to learn anything of his history. His brother George died near Sellersville, Bucks county, , at the advanced age of 92 years, 2 months and 10 days, respected by all his friends and neighbors. He, likewise, was arrested during the trouble; was tried and convicted but received a much lighter sentence than his brother John, being fined one hundred dollars and sentenced to undergo an imprisonment of 6 months. Heaney was the owner of a small house and lot. These two men were the advisors and confederates of John Fries, Getman being the most in his confidence. They lacked the intelligence and shrewdness of their leader, but were active in the cause and rendered him important service. Such were the three men who were the head and front of the “Fries Rebellion.” Thus we have related the cause of the rebellion, with some account of the principal actors in it, and, in the next chapter, we shall give our readers a brief history of the overt acts of the insurgents.

- Daniel Shays, born , at Hopkinton, Mass., served as ensign at the battle of Bunker’s Hill, and attained the rank of Captain in the Continental Army. In he took part in the popular movement in Western Massachusetts for the redress of alleged grievances, and became the leader in the rebellion which bears his name. Shays, after being pardoned, removed to Vermont and thence to New York, where he died . In his old age he was allowed a pension for his services during the Revolution.

- The “Whiskey Insurrection” was a disturbance in the south-western section of Pennsylvania, caused by Congress imposing a tax on all ardent spirits distilled in the United States three years previously. The object of the tax was to improve the revenues of the government. It is charged that Genet, the French minister, and his partizans incited the people of the distilling regions to resist the tax collectors. The disaffected rose in arms. Washington issued two proclamations warning the insurgents to disperse but, instead of obeying, they fired upon and captured the officers of the government. A military force 15,000 strong, was then organized and sent into the disturbed district, to enforce the law, but the insurgents had already scattered when the troops arrived. The whiskey tax was a measure of the Federal party.

- Governor Henry Lee, Virginia, who commanded the troops of the Government in the “Whiskey Insurrection,” was the famous “Light Horse Harry” of the Revolution, and rendered Washington distinguished service as a partizan cavalry officer. He was born in Westmoreland county, Va., . He was appointed by Congress to deliver the funeral oration on Washington, .

- Bucks, one of the three original counties of Pennsylvania, and organized with Philadelphia and Chester, , lies in the south-eastern coroner of the State, Northampton joining it on the northwest and Montgomery, cut off from Philadelphia, , bounds Bucks on the southwest. The district, where opposition to the House tax law prevailed, was settled mainly by Germans; there was no opposition to speak of outside of a few townships in the upper end of Bucks and the lower end of Northampton. Berks was formed from Chester, Philadelphia and Lancaster, .

- Seth Chapman, commissioner for the Third District, and citizen of Bucks county, received his commission and instruction early in the autumn and immediately qualified. He was a relative of James Chapman and possibly a brother.

- Jacob Eyerley was a Moravian and a man of some influence.

- Reading, the county seat of Berks, was laid out in the Autumn of , on a tract of 450 acres for which warrants had been taken out by John and Samuel Finney, . It is now a prosperous and wealthy city of some 70,000 inhabitants.

- James Chapman was born in Springfield township, and at this time was living in Richland, although I do not know when he moved into it. He lived on a farm some years ago the property of P. Mayer, on the road to Milford Square, one mile west of Quakertown. He belonged to Richland meeting, , when he and ten other leading members were disowned for subscribing the oath of allegiance to the Colonies. The Chapman family is one of the oldest in the county, the first ancestor in America immigrating from England and settling in Wrightstown township, . The Hon. Henry Chapman, lately deceased, Doylestown, was a lineal descendant of the first settler. Seth Chapman, one of the assessors, was a member of the same family. For a further account of James Chapman see chapter 9th.

- John Rodrock was a resident of Plumstead township when appointed, but I do not know that he was born there. He kept the tavern at what is now Plumsteadville, on the Easton pike, then known as “Rodrock’s tavern,” and this is where the assessors held their first meeting. He kept it down to about seventy-five years ago, and was the only house there. In it was called “James Hart’s tavern.” Rodrock owned about 300 acres of land in the vicinity, at his death, more than a half century ago. The village now contains 25 dwellings, with tavern, store, a brick church and extensive carriage works.

- Everard Foulke was a member of the Foulke family, Richland, in the neighborhood of Quakertown, and was probably appointed from that township. They were Friends. His first ancestor in this country was Edward Foulke, who came from North Wales, , and settled in Gwynedd township, Montgomery county, and from there removed to Richland. The late Benjamin Foulke, Quakertown, was a descendant of the same common ancestor as Everard.

- Cephas Childs, or Child, the correct spelling, was of a Plumstead family, but I do not know that he lived there when appointed. A Cephas Child, or Childs, was there as early as about , and was a Friend. He was a member of the Assembly, . Among the descendants of the first settler, was the late Colonel Cephas G. Child, Philadelphia. A Cephas Child died in Plumstead in , at the age of 90, probably his son, or grandson.

- Milford township, in the northwest corner of Bucks county, was settled by Germans as early as , and organized, . It is one of the largest and most populous townships in the county, and is a fine agricultural region.

- Hatfield township, Montgomery county, is bounded on the northeast by Bucks county. It was laid out about and probably derived its name from the parish and town of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, England. The population is over 2000. In it contained one tavern, two grist mills, one saw mill and one tannery. It is 334 miles long by 3 miles wide, with an area of 7100 acres.

- Whitemarsh township, Montgomery, lies in the Schuylkill Valley. It has an area of 8697 acres, and is one of the most populous townships in the county. In the quality of its limestone, marble and iron ores it is not surpassed in the State. “Whitemarsh lime,” for whitewashing, finds its way all over the country. It was settled as early as . It is rich in Revolutionary incidents, and, within its limits, some important movements were made by the two opposing armies in Fall of and Winter of . It is cut by the North Pennsylvania railroad and is twelve miles from Philadelphia.

- Mather’s mill is in Whitemarsh township, Montgomery county, near the intersection of the Bethlehem and Skippack turnpike, a mile below Fort Washington. It was built by Edward Farmer, ; rebuilt, , by Mather, and is now or was lately owned by the Otterson estate. The mill is on the Wissahickon creek. Edward Farmer carne to America with his father, , and settled in Whitemarsh. He became prominent in affairs, and died , in his 73d year.

- The Galloways came from Maryland to Philadelphia, where Joseph was born about and marrying Grace Growden, removed to Bucks county. He owned a large landed estate in Bucks that came through his wife. He abandoned the Whig cause during the Revolution, and went to England, where he died, . He was active in the early part of the struggle; was a member of the first American Congress, , and, at that time, no man stood higher in the Province. He was a lawyer, and a man of great ability.

- Charlestown, now called Trumbauersville, a place of some sixty families, is built for half a mile along the road leading from Philadelphia to Allentown. At the time of the Fries Rebellion it could not have had more than one or two dwellings, besides the tavern, now known as the Eagle. It is the seat of cigar factories, and, at one time, turned out 2,000,000 a year. The first church building was erected ; rebuilt, , and again . It is now a Union church.

- Caleb Edwards was probably a descendant of John Edwards, who came with his wife from Abington, Montgomery county, to the neighborhood of Quakertown about with the Morrisses, Heackocks, Jamisons, Joneses and others. He must have been appointed from Richland or a neighboring township.

- Quakertown, Richland township, is at the intersection of the Milford Square and Newtown, Hellertown and Philadelphia roads, all opened at an early day. Here a little hamlet began to form over a century and half ago, and as the settlers were principally members of the Society of Friends, the name “Quakertown” was given it. A tavern was opened as early as ; a post office, 1803; a public library founded ; and it was incorporated into a borough in . The population was 863 in , and 2169 in . In the borough limits were extended to include Richland Centre, a village that had grown up about the station on the North Penn. Railroad, a mile to the east. The population of the borough is about 3000. Quakertown is the centre of a rich and populous country.

- “Camp Hill” is an elevation in Whitemarsh township, Montgomery county, Pa., and so named because a portion of the Continental Army occupied it during the Fall, , in the operations following the occupation of Philadelphia by the British. It lies on the left of the North Pennsylvania Railroad below Fort Washington Station, the next station below it being known as “Camp Hill,” on the west side of the railroad. The contiguous country was the scene of military operations of that period by Washington’s army.

- The “Crooked Billet,” the present Hatboro, a village of a thousand inhabitants, is in Moreland township, Montgomery county, Pa., half a mile from the Bucks county line, on the North-East Pennsylvania Railroad. It has a bank, a weekly newspaper, an academy, three churches, and a valuable library, founded, . It is thought to have been first settled by John Dawson, who, with his wife and daughter, and probably two sons, came from London to Pennsylvania, . He was a hatter and a member of Friends’ Meeting. The place was called “Crooked Billett” from a crooked stick of wood painted on the sign that hung at the tavern door in ye olden time.

- John Lacey, captain in the Continental Army and subsequently a Brigadier General of militia in the Revolution, was born in Buckingham township, Bucks county, Pa., . The family were members of the Society of Friends, and immigrated from the Isle of Wight, England, and settled in Wrightstown among the first settlers. He was commissioned captain in the 4th Pennsylvania regiment, commanded by Col. Anthony Wayne, ; serving in the campaign in Canada of that year, returning home on the recruiting service in . He shortly afterward resigned his commission, because of some unjust treatment by Colonel Wayne, but continued his activity in the cause of the Colonies. He was commissioned a Sub-Lieutenant of Bucks county, ; a Brigadiere General of the State, , before he was 23, taking the field shortly afterward. During that Winter and Spring he had command of the country between the Delaware and Schuylkill, and rendered efficient service. The action at the Crooked Billet took place . In General Lacey was chosen a member of the Executive Council of the State and, as such, served for two years. , he married a daughter of Colonel Thomas Reynolds, New Mills, now Pemberton, N.J., whither he removed the Fall of that year, or beginning of . He entered into the iron business, and died there . The late Dr. William Darlington, West Chester, Pa., married a daughter of General Lacey.

- Stover’s Mill is in Rockhill township, Bucks county, a few miles from Sellersville, on the North Pennsylvania Railroad, and was owned by a member of the family of that name a few years ago.

- Hagersville is situated on the Old Bethlehem Road, in the north-west corner of Rockhill township. It has a store, tavern, the usual village mechanics, and some dozen dwellings. At this point the road is the dividing line between Bedminster and Rockhill townships. The village took its name from Colonel George Hager, a prominent man and politician over half a century ago. He was a candidate for sheriff .

- Plainfield township, Northampton county, was settled as early as and organized shortly after , but the records of its organization are lost. It was a frontier township of Bucks county at the time of its organization.

- We were told by a descendant of Frederick Heaney that he was of German descent, as his name implies, his father, Johannes Horning, having immigrated from the Palatinate about , and settled at what was afterward known as “Heaney’s Mill,” Rockhill township, Bucks county. Frederick was born there . At the beginning of the present century he removed to Northampton county, where he died, . Governor Simon Snyder commissioned him justice of the peace, for a district of Northampton, composed of the townships of Upper and Lower Mount Bethel and Plainfield. , which office he held until his death. He was buried at Plainfield Church, near the Wind Gap. A number of his descendants live in Monroe and Northampton counties.

Ⅱ. Insurgents Prepare to Resist the Law

John Fries was probably the first to array himself against the law, immediately upon its passage and promulgation. His own intense hostility begat the desire that his neighbors and friends should agree with him in feeling, and he labored with great zeal to this end. When going about the county crying vendues, he was careful to sound the people as to how they stood upon the subject of the new tax, and was never backward in expressing his own opinion. From a warm supporter of Mr. Adams and his Administration, he suddenly became their most bitter enemy, giving vent to his feelings in terms of unmeasured denunciation. He reasoned with, persuaded, and threatened all and seemed to make it his business to create enemies to the act. He was thus active during the Fall months of , and, by the end of the year, had raised a fierce opposition to the law and those who were to carry it into execution. He was particularly hostile to the house-tax, and declared openly that no assessments should be made in Milford township, nor tax collected if he could prevent it. We were informed by his son Daniel, then about eighteen, and had a distinct recollection of the events transpiring, that several private meetings were held at his father’s house before any public demonstration was made. His friends and neighbors met there to talk about the law, and determine, in a quiet manner, what was best to be done. At these conferences Fries always took the lead, and his stronger mind assisted to mould the opinion of others.

The time had now arrived when some more active measures must be taken, and opinion changed to deeds. The period approached when the assessors were to commence their duties, and some public demonstration was necessary to prevent them carrying the law into effect. With this object in view, about , notices, without any names signed to them, were put up at various places in the township, calling a public meeting for , at the public house of John Klein, on the road leading to Gary’s tavern, two miles southwest from Charlestown. On , a number of persons assembled at the place of meeting late in the afternoon. The two most active and noisy men present were John Fries and George Mitchel,1 who then kept the public house more recently occupied by Eli L. Zeigler, at the west end of Charlestown. This tavern was one of the places where the malcontents of the neighborhood assembled at evenings to talk over their grievances. Few, if any, at the meeting appear to have had a very definite idea of what should be done; they disliked the house-tax and were opposed to paying it themselves, or permitting others to do so; but, beyond this, there was no plan of opposition, at this time. The law was discussed and its authors denounced in violent terms.

Some expressed a doubt whether the bill had yet become a law. The newspapers of the day mentioned that an amendment had lately passed Congress, which seemed to confuse the understanding of the people, and rendered them undecided as to whether the law was actually in force. After the matter had been sufficiently considered and the sense of the meeting fully explained, Fries, with the assistance of the publican, Mitchel, drew up a paper that was approved and signed by about fifty of those present. What the exact import of this paper was has never been determined, as neither the original nor a copy fell into the hands of the authorities. It is supposed, however, to have contained merely a statement of the views of the signers upon the subject of the tax, and their determination to oppose the execution of the law. Before adjourning, however, a resolution was passed requesting the assessors not to come into the township to make the assessment, until the people were better informed whether the law was really in force; and one Captain Kuyder appointed to serve a copy of the resolution upon them. Having transacted the business which brought them together, the people quietly dispersed and returned to their homes. The meeting was conducted in the most orderly and peaceable manner, and there was no appearance of disturbance on the part of anyone.

Our readers will bear in mind, that Mr. Chapman, commissioner for the counties of Bucks and Montgomery, met the assessors of the former county at the public house of Mr. Rodrock, the latter end of December, to deliver to them their instructions how to proceed in the assessments. Immediately after this meeting, these officers commenced the assessment in the respective townships assigned them. They proceeded without any trouble, or appearance of opposition, in all the townships but Milford, and even there the people, notwithstanding the late agitation and excitement against the law, quietly acquiesce in its execution. It is true they did not like it, and would rather have avoided paying the tax, but they had abandoned all intention of resisting the law. Childs and Clark had both been appointed for Milford, and, before separating, fixed upon a day when they would begin in that township. Childs had also one or two other townships assigned him, and, it was arranged between them, they should assist each other, two days at a time, alternately. As Childs had already made some assessments in his own district, he agreed to help Clark whenever he should be ready to begin the work. Before the meeting adjourned at Rodrock’s, the principal assessor named an early day to meet again, and make return of what they had done. Mr. Childs went to assist Clark according to agreement, but, when he reached his house, finding the latter was not able to go on with the assessments, he returned to finish up his own district. In Milford the excitement was still running high; and as threats of serious injury had been made against the assessors, who were forbidden to enter the township, they declined to attempt it.

Fries and his friends had inflamed the minds of the people to such degree, that in some parts of the township they were almost in a condition to take up arms. The assessors met at Rodrock’s, to make returns, on , but as they did not complete their business that day they adjourned to meet on .

In the unsettled condition of things in Milford, the principal assessor, James Chapman, determined to take some steps to satisfy the people of that township in relation to the tax. For this purpose he thought it advisable to have a public meeting called at some convenient place, where he would explain the law, but not trusting altogether to his own judgment in the matter, he went to George Mitchel’s on , and consulted him. The latter agreeing with the principal assessor, he was requested to lend his assistance in getting up the meeting and assented. Word was sent to Jacob Hoover,2 who owned and lived at a mill on Swamp creek, on the road leading from Trumbauersville to Spinnerstown, about one mile west of the former place, and the same later occupied by Jonas Graber,3 to give notice of the meeting to the people of his neighborhood; and also to inform them they would be permitted to select their own assessor, and that any capable man whom they might name would be qualified. The offer, however, did not meet with much favor in that section of the township, and the people declined to have anything to do with it. There seemed to be a general disposition, among the friends of Mr. Adams in the township, to have a public meeting called notwithstanding the failure of the first attempt — to endeavor to reconcile matters; and Israel Roberts and Samuel Clark both saw Mitchell upon the subject. A few days after, Mr. Chapman again sent word to Mitchell to advertise a meeting, which he accordingly did, and the time fixed was the latter end of , the place, his own tavern. The notice given was pretty general, and a large assemblage was expected.

The Jacob Hoover here spoken of was the uncle of Reuben L. Wyker, who lived near Rufe’s store in Tinicum, and was active in assisting Fries. It is said he manufactured cartouch boxes for the use of the insurgents, and otherwise made himself useful to them. He escaped capture by having timely warning of the approach of the troops. George Wyker, also of Tinicum, and uncle of Reuben L., was in Philadelphia at market, at the time, and there learned that Jacob Hoover was to be arrested, and that a warrant had already been issued. Being anxious to prevent him falling into the hands of the federal authorities, he hastened home, as soon as he had sold out his marketing, to give warning of the danger. He told his father what he had heard in the city. The latter was Nicholas Wyker, who lived on the same farm where Alfred Sacket lived in more recent years, on the hillside near Rufe’s store. He immediately set off for Hoover’s, whom he found at home, apparently very much unconcerned, but entirely ignorant of the danger that threatened him. Even when told of the arrangements made to arrest him, he did not seem to give it much importance; but, while they were in conversation Hoover looked out the window and saw the troops coming up the road. This reminded him of the necessity of fleeing. He immediately ran out the back door, and, keeping the house between him and them, made his way to a neighboring thicket, into which he escaped. When the soldiers arrived at the house, they surrounded it and entered, but the bird had flown, and Hoover was nowhere to be found. After a thorough search, the officer gave up the pursuit and returned with his soldiers, much chagrined. Hoover kept out of harm’s way until the affair had blown over, when he returned home. He afterward removed to Lewistown, in this State, where he died.

In the meantime the adjourned meeting to be holden at Rodsock’s tavern, on , at which the returns of the assessments were to be made, came off. All the assessors, except Mr. Clark, were there and reported the assessments had been nearly completed in all the townships except Milford, where nothing had as yet been done. The assessor of this township had been so much intimidated and threatened he was afraid to go about in the discharge of his duties. Mr. Foulke also expressed some fears of going into the township, as threats had likewise been made against him, and he anticipated trouble. This state of things changed his mind in regard to permitting the people of the township to select their own assessor, and he now gave his consent to it, hoping it would conciliate them. He used his influence with the commissioner to induce him to agree to the same, and he finally yielded and gave his permission. He notified the assessors, at the same time, that in case the people did not accept the terms offered them, and choose some person to discharge the duty, they would have to go into the township, and assist Clark to make the assessments. Proposals were made to the various assessors as to which would assume the duty, but each one had some excuse to give why he could not go, showing great unwillingness to place themselves in the way of danger. The unsettled condition of Milford alarmed them, John Fries and his friends being the terror of these officers.

The time for the meeting advertised to take place at Mitchell’s had now arrived, which was holden on a , and a great many persons were at it. Everhard Foulke and James Chapman were present on the part of the assessors. The meeting was called for the purpose of reading and explaining the law, as they were extremely ignorant of its provisions and operations; but they behaved in such a disorderly manner nothing could be done. A general fear appears to have seized upon those present. Mr. Foulke used his best endeavors to remove it, but without avail. In their present state of mind, as he well knew, any explanation of the law on his part would have but little, if any, effect, and he did not even attempt it. Among the well disposed citizens present was Jacob Klein, who, at the request of Mitchell, made an effort to calm the fears of the people, but he met with no success, for the clamor and noise were so incessant he could not be heard. Israel Roberts proposed to read the law to them, but they would not listen to him, and drowned his voice in their shouts. Conrad Marks, who afterward became an active participant in the disturbance, was at the meeting, but it does not appear that John Fries was there, which is hardly reconcilable with his known activity in opposing the law. The assessors seeing nothing could be done toward satisfying their minds on the subject of the tax, and removing their prejudice and opposition to the law’s execution, declined to take further part in the meeting and returned home.

The officers, upon this occasion, met with a signal failure in their attempt to induce the people to acquiesce in the assessments, and the result of the meeting gave encouragement to the opposition. In the subsequent trial of John Fries before the United States Court, Mr. Chapman, who was a witness on the part of the Government, gives the following account of what took place at this meeting, so far as it fell under his own observations. He says;.

I got there . Just as I got to the house, before I went in, I saw ten or twelve people coming from towards Hoover’s mill; about the half of them were armed, and the others with sticks. I went into the house and twenty or thirty were there. I sat talking with some of my acquaintance that were well disposed to the laws. Conrad Marks talked a great deal in German; how oppressive it was, and much in opposition to it, seeming to be much enraged. His son, and those who came with him, seemed to be very noisy and rude; they talked in German, which as I did not know sufficiently, I paid but little attention to them. They were making a great noise; huzzaing for liberty and Democracy, damning the Tories, and the like. I let them go on, as I saw no disposition in the people to do anything toward forwarding the business. Between four and five I got up to go out; as I passed through the crowd towards the bar, they pushed one another against me.

No offer was made to explain the law to them while I staid; they did not seem disposed to hear it.

They did not mention my name the whole time of my being there, but they abused Eyerly and Balliett and said they had cheated the public, and what villains they were. I understood it was respecting collecting the revenue, but I did not understand near all they said. I recollect Conrad Marks said that Congress had no right to make such a law, and that he never would submit to have his house taxed.

They seemed to think that the collectors were all such fellows; the insinuation was that they cheated the public, and made them pay, but never paid into the Treasury. After getting through the crowd to the bar, I suppose I was fifteen minutes in conversation with Mitchell; he said perhaps they were wrong, but the people were very much exasperated. Nothing very material happened, and I asked Mr. Foulke if it were not time to be going. So I got into my sleigh and went off; soon after they set up a dreadful huzza and shout.

Israel Roberts and other witnesses, on the part of the prosecution at the trial of Fries, and who was present at the meeting at Mitchel’s, testified as follows:

At the last meeting at Mitchell’s there appeared a disposition to wait till they should have assistance from some other place. It was said that a letter had arrived to George Mitchell, from Virginia, stating there were a number of men, I think ten thousand, on their way to join them; the letter was traced from one to another, through six or eight persons, till at last it came from one who was not there. Some of the company at that time were armed and in uniform. I do not recollect what was said when the letter was mentioned, but they appeared to be more opposed to the law than they were before.

At the meeting at George Mitchel’s, at which Mr. Foulke and Mr. Chapman were present, which was held for the purpose of explaining the law, there were a number, about twelve came up in uniform, and carrying a flag with “Liberty” on it. They came into the house and appeared to be very much opposed to the law, and in a very bad humour. I proposed to read the law to them; and they asked me how I came to advertise the meeting; I told them I did it with the of a few others; one of them asked me what business I had to do it; I told him we did it to explain the law. He looked me in the face and said, “We don’t want any of your damned laws, we have laws of our own,” and he shook the muzzle of his musket in my face, saying, “This is our law and we will let you know it.” There were four or five who wished to hear it, but others forbid it, and said it should not be read, and it was not done.

On his way home from the meeting, Mr. Chapman stopped at the public house of Jacob Fries, who then kept the tavern more recently occupied by George L. Pheister, at the east end of Trumbauersville, where he waited for Mr. Foulke to come up, who arrived soon after. Clark was also there. Mr. Chapman had a conversation with him upon the subject of taking the rates in the township, when he declined to have anything more to do with it. He gave as a reason for this course that it would not be safe for him to undertake the assessments, and that he did not feel justified in endangering his life in order to assist to have the law carried into execution. He thus washed his hands of the whole business, and resigned his commission. It was now evident to Chapman and Foulke, that the other assessors would be obliged to make the assessments in Milford, if they were made at all, and they deemed it their duty to take immediate steps to have it done. They agreed to meet the assessors at Quakertown, on , in order to commence the work, and, before they left for home, Mr. Chapman asked each one to be present at the time and place appointed. When the day arrived for the meeting, but three of the assessors attended, Rodrock, Childs and Foulke, in addition to the principal, Mr. Chapman. They waited until evening without transacting any business, expecting others would arrive but none came, when they adjourned to meet at the house of Mr. Chapman, at .

As soon as it became noised about that the assessors had resolved to come into the township to take the rates, those opposed to the law renewed their activity against it. The people were told by the leaders that the assessments must not be made, and force would be used to prevent it, if necessary. The information that the assessors, who were now looked upon as enemies to republican institutions, were coming, increased the excitement, and the people began active measures to oppose them. Captain Kuyder, who was in command of a company of militia, called them into service to assist in driving the assessors out of the township. He notified his men to meet him at his mill, on , where some fifteen or twenty assembled. Early in the morning, while he was abroad in the neighborhood, he met his acquaintance, William Thomas, whom he invited to go to the mill and see his men. He accepted the invitation and accompanied the Captain there. His men were getting together. When he arrived he found a number already assembled, a portion of them armed and others soon came up. After remaining a little while the Captain ordered his men to take up the march for the tavern of Jacob Fries, Trumbauersville.

By the time they reached the village a considerable number of stragglers had been attracted, who helped to swell the throng. They marched along the main road until they came to the tavern, when they drew up in front of it and halted. Here a number more joined them, making about thirty in all. The people assembled expressed a desire to see the assessors, whom they knew were somewhere in the township making assessments; and a couple of horsemen were sent off to hunt them up and notify them they were wanted. They were instructed, in case they should find them, to take them prisoners, and either conduct them to Quakertown or bring them to Fries’ tavern. Soon after the messengers had left, it was proposed that Captain Kuyder’s company and the rest of the people assembled, should march to Quakertown and they immediately started down the road for that place. They presented a somewhat martial, but very irregular, appearance; the greater part being either armed with guns or clubs and accompanied with drum and fife. As they passed through the country they attracted much attention, and the sounds of their martial music were heard “far o’er hill and dale.” They, who were not cognizant of the movement, and hardly knew what to make of the demonstration, went to the roadside to see what was going on. As they marched along the road they increased in number, and, by the time they reached their destination, there were more than a hundred in the company. This movement was the commencement of the overt acts of resistance, and had an important bearing on the subsequent conduct of those who became insurgents in name and deed.

- We are not able to learn anything further of George Mitchell than is mentioned here.

- The Hoovers, or Hubers, immigrated from Switzerland , and settled in Milford township. The father’s name we do not know, but his wife’s was Ann, who was born , died , and was buried at the Trumbauersville church. Henry, one of the sons, made powder for the Penna. Committee of Safety, , at a mill on Swamp creek. Another son, John Jacob, was probably the “Jacob Hoover” mentioned here.

- This was in ; the present owner we do not know.

Ⅲ. Fries Captures the Assessors

The three assessors, Chapman, Foulke and Childs, met, on the morning of , at the house of Mr. Chapman as had been agreed upon, and thence proceeded into Milford township to make the assessments. They thought it advisable to to call upon Clark, in the first instance, and see if they could not prevail upon him to go with them and divide the township, so as to complete their work in a short time. When they arrived at his house he was absent from home, and it was thought best for Mr. Chapman to go in search of him. Learning he had gone to assist one of his neighbors to move, he went to Jacob Fries’1 tavern to wait for him to return. In a little while he came. Upon being asked to assist in assessing the township he positively refused, saying he might as well pay his fine, even if it should take all the property he had. Finding that nothing could be done with him, the subject was dropped. While Mr. Chapman was at the tavern, John Fries came up. After passing the compliments of the day, Fries remarked to him he understood he had been insulted at one of the meetings in the township, which, he said, would not have been the case had he been present, and expressed his regret at the rudeness with which the assessor had been treated. The following interview then took place between the two, as sworn to on the trial of Fries:

I told him (Fries) I thought they were very wrong in opposing the law as they did; he signified that he thought they were not, and that the rates should not be taken by the assessors. I told him the rates would certainly be taken, and that the assessors were then in the township taking them. I repeated it to him, and he answered, “My God! if I were only to send that man (pointing to one standing by,) to my house to let them know they were taking the rates, there would be five or seven hundred men under arms here to-morrow morning by sunrise.” He told me he would not submit to the law. I told him I thought the people had more sense than to rise in arms to oppose the law in that manner; if they did, government must certainly take notice of it, and send an armed force to enforce the law. His answer was, “if they do, we will soon try who is the strongest.” I told him they certainly would find themselves mistaken respecting their force; he signified he thought not; he mentioned to me the troop of horse in Montgomery county, and the people at Upper and Lower Milford,2 and something about infantry who were ready to join. He said he was very sorry for the occasion, for, if they were to rise, God knew where it would end; the consequences would be dreadful; I told him they would be obliged to comply; he then said huzza, it shall be as it is in France, or will be as it is in France, or something to that effect. He then left me and and went off.

While Mr. Chapman was waiting for Clark at Jacob Fries’ tavern, and holding the strange interview with John Fries, the other assessors were engaged in taking the rates around the township. The first house they came to was Daniel Weidner’s, at the west end of Trumbauersville, and occupied by Geo. Zeigler, . Childs went in first and told Mr. W. that he had come in order to take the assessment under the revenue law of the United States. He appeared to be in a bad humour at the proceeding, and declined to give any information of his property. The assessor reasoned with him, and pointed out the impropriety of his conduct and what would be the consequence of his opposing the law. He was told he might have ten days to consider the matter, at the end of which time he would be able to determine what he ought to do. He professed not to know whether the law was in force, and said many other things in extenuation of his conduct; charged the assessor with receiving very high wages, &c. Mr. Childs explained that the law was in force and how a committee of Congress had reported against the expediency of repealing it. At last, Weidner, overcome by persuasion, or argument, consented to be assessed and gave up his property, saying to the assessor, “take it now, since it must be done.” Childs then continued on his round, walking and leading his horse from house to house, until he reached Mitchel’s tavern,3 where he found the other two assessors, who had arrived a little while before. Weidner got there in advance and was again railing out against the law; and said that the houses of high value were to pay nothing, while smaller ones, and of small value, were to pay high. He was again reasoned with, and finally became apparently reconciled, and gave up an additional piece of property to be assessed. He seemed to take the matter much at heart, however, and exclaimed, “They will ruin me; what shall I do?” The assessors then continued on their way toward Jacob Fries’ tavern, where they were to meet the principal assessors by appointment, assessing several houses as they went along. They had assessed some fifty or sixty houses in the whole, up to this point, and had done it without opposition. In every case but one the people were at home, and there a notice was left. They arrived at the tavern a little before dinner. As Mr. Childs was going into the door he was met by John Fries, who shook him by the hand, said he was glad to see him, and asked him to take a drink.

The assessors dined at Jacob Fries’. After dinner, and while they were sitting at the fire, John Fries came into the room. He addressed himself to Mr. Foulke and Mr. Chapman, and said they were men he greatly esteemed, and was sorry they had placed themselves in that position. He here proclaimed his opposition to the law; and said “I now warn you not to go to another house to take the rates; if you do you will be hurt.” Without waiting for a reply he turned upon his heel and went out of the room. He seemed irritated and in anger. He said nothing more to them while they remained there. After a conference, the assessors concluded to pay no attention to the threat of John Fries, but proceed with the assessments. While at the tavern, Mr. Childs took the rates of Jacob Fries’ house to which no opposition was made. It was then agreed that Rodrock and Foulke should go together, and Childs by himself to assess the houses of some who were known to be quiet and orderly people. They then mounted their horses and rode away in discharge of their duty. They found a marked difference, between the English and German, to be assessed; with the former they had no difficulty, except at one place, where the family said there were some bad people living in the neighborhood who would do them injury if they submitted to the rates. Messrs. Rodrock and Foulke continued on until about sunset without meeting any hindrance, or seeing any sign of opposition to the execution of the law. They were now going to the house of a man named Singmaster, and, as they turned down a lane out of the public road, they heard some person halloo to them; when, stopping and looking round, they saw John Fries and five men coming toward them. Fries was in front, and upon coming up he said he had warned them not to proceed with the assessments, but as they would not obey him he had now come to take them prisoners. Rodrock asked him by what authority he had stopped them, to which he made no reply, but immediately grappled for the bridle of his horse. He wheeled the horse around at the moment, which caused Fries to miss the bridle and catch the rider by the coat tail, but the latter succeeded in tearing away and freeing himself from his grasp. Fries then rode off, but, before he had gone far, he turned about and approached the assessor again. He now cursed Rodrock, and, remarked to him, if he had a horse he would catch him. He offered no further insult, but returned to his companions. Mr. Foulke was less fortunate. The comrades of Fries surrounded him and secured him without resistance; but when in their power they offered him no injury, but treated him with kindness. When Fries returned to his men and found Mr. Foulke in their hands, he at once directed them to let him go, giving as a reason that as they were not able to catch Mr. Rodrock, they would not detain him. As the assessor was released Fries remarked to him, “I will have seven hundred men together to-morrow, and I will come to your house, and let you know we are opposed to the law.” Being at liberty once more the assessors proceeded to the house of Philip Singmaster, who lived on the road leading from Trumbauersville to Philadelphia, half a mile from the former place, and in a house occupied by Zeno Frantz, . They found him at home, and, upon informing him of their business, were permitted to assess his house without opposition. While here Mr. Childs rejoined them as had been agreed upon when they parted company at the tavern of Jacob Fries. They now compared opinions, and came to the unanimous conclusion they would not be justified in further attempt to take the rates in Milford township, on account of the violent opposition of the inhabitants, led on by John Fries; and the principal assessor was to give notice of this determination to the commissioners. They thereupon ceased to make assessments in the township and turned their faces homeward on the afternoon of .

Meanwhile the insurgents continued their march toward Quakertown, where they arrived about noon, or shortly after. In a little while the party of Capt. Kuyder was joined by John Fries and companions and several others. They halted at the tavern of Enoch Roberts, the same kept by Peter Smith, , when those on horseback dismounted, and, as many as could, went into the house. The scene around the tavern was one of noise and confusion, while those inside were no less boisterous. They were hallooing, and cursing and swearing; the most violent were denouncing John Adams, the house-tax, and the officers who were to execute the law; some were drumming and fifing, apparently endeavoring to drown the hum of confused voices in the strains of martial music, and numerous other ways were resorted to, to give vent to their feelings. The bar of Mr. Roberts was pretty generously patronized, and that liquor flowed so freely the excitement and confusion were increased. Fries, expecting the assessors to come that way on their return home, he had made up his mind to arrest them if nothing transpired to interfere with his arrangements.

When the assessors ended their conference at Philip Singmaster’s, after having assessed him, they started directly homeward, having to pass through Quakertown their most direct road. Messrs. Foulke and Rodrock rode together, while Mr. Childs preceded them a short distance. When they arrived at the village, they found it in possession of the crowd of people already mentioned, under the control of John Fries and Conrad Marks. Some were in uniform and others in their usual working clothes; some were armed with guns, and others carried clubs. The noise and confusion they made were heard some time before the assessors reached the town. The testimony, given on the trial, shows they were congregated at two public houses, one already mentioned as being kept by Enoch Roberts, whereas the other was called “Zeller’s tavern.” We have been at considerable trouble to locate this latter public house, but have been unable to do so. The house, in which Richard Green lived, , on the road to the railroad station, is said to stand on the site of an old tavern which may have been the one the witnesses called “Zeller’s.” On the other hand it is said, by the old residents of Quakertown, that Enoch Roberts had a son-in-law named N.B. Sellers, who assisted him to keep the public house he then occupied. The name of Zeller may have been intended for Sellers, and is possibly a misprint in the report of the trial, both meaning one and the same place.

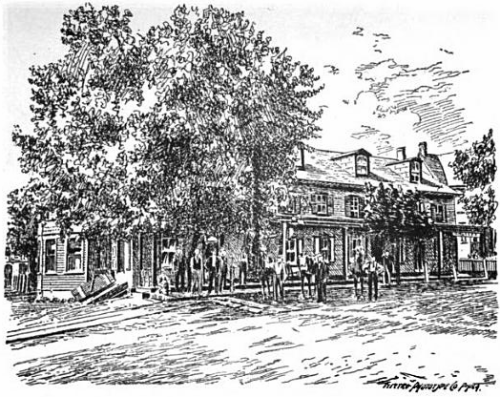

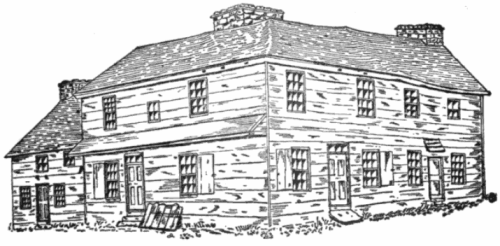

Sellers’ Tavern, erected about .

When the insurgents saw the assessors coming they set up a great shout, and, as soon as they had approached within hailing distance, ordered them to stop. This they did not heed, as they had determined not to place themselves in their power if it could be avoided. As they entered the village Messrs. Foulke and Rodrock separated, and did not ride in together, Mr. Childs having already stopped at the house of a neighbor just on the edge of the town. Rodrock now rode in advance, and, when he had passed about half through the crowd, without giving heed to their commands to stop, they started to run after him from both sides of the road, some carrying clubs and others muskets, and made motions as if they intended to strike him. John Fries was standing upon the porch of the tavern, and when he saw Rodrock coming up he called out to him to stop, but, paying no attention to it, some of the men ran after him. The assessor, seeing himself pursued, wheeled his horse and demanded of Fries what he wanted with him. This seemed to excite the men the more, and they replied to him with curses, and ordered him, in an authoritative tone, to deliver himself up. To this he replied he would not do it while they addressed him in such language as they had applied to him. Some one in the crowd then gave the order to fire at him, when two men standing near the tavern door pointed their guns but did not fire. He now rode off toward home, and when they saw him making his escape, they again commanded him to stop; some making demonstrations to get their horses and pursue him, but they did not. When he reached the house of Daniel Penrose, seeing Jacob Fries and John Jamieson there, he halted and related to them what had taken place. He appeared to be much alarmed; said that Foulke and Childs had been captured, and was afraid they would be killed. He requested Jamieson to return to the village, and prevent them being hurt, which he declined doing unless Rodrock would accompany him; but he was finally prevailed upon to go. He found the two assessors in the hands of the mob but not injured.