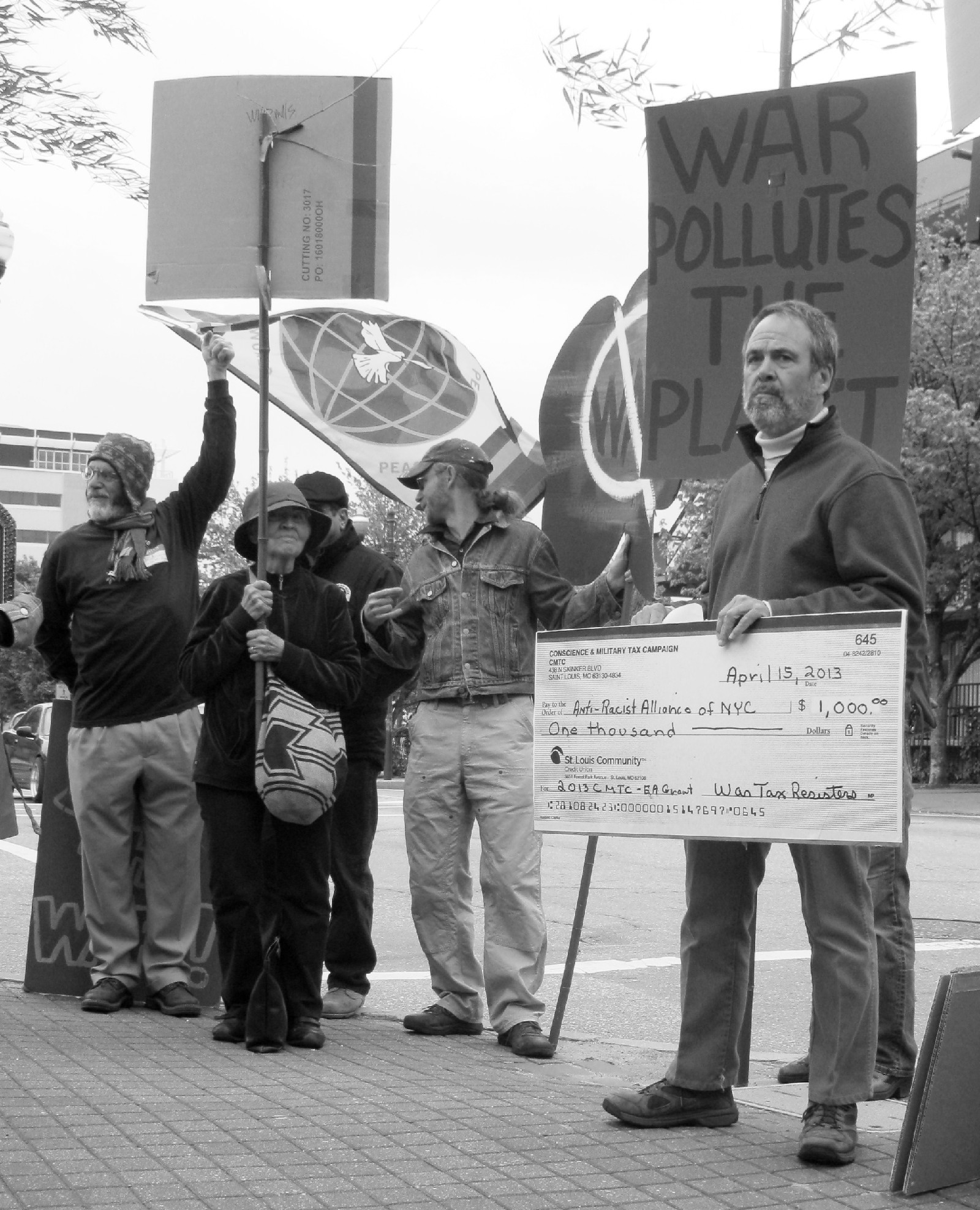

Here are a couple of examples of American social security tax resisters from back in the day. First, from the Amsterdam, New York, Evening Recorder from :

Man, Jailed for Defying NRA in , Now Refuses to Pay Security Taxes

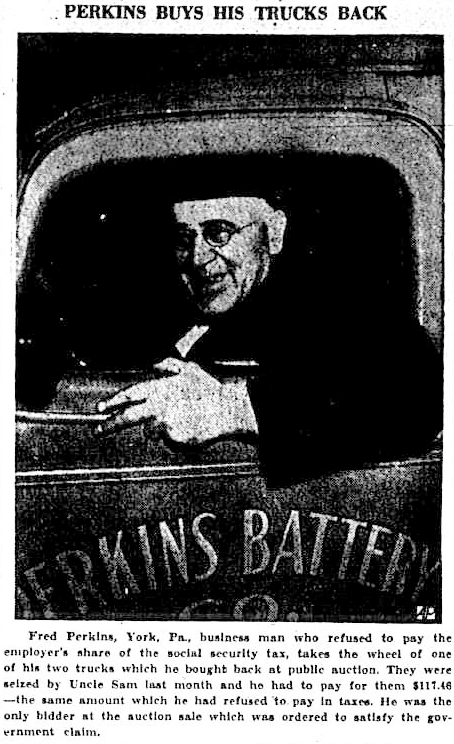

Uncle Sam to Sell Trucks Of Battery Manufacturer To Satisfy $105 Claim; Penna. Also Files Suit

York, Pa., . — (AP) — Uncle Sam raised an auctioneer’s hammer today above two trucks seized from government-defying Fred Perkins and said more of Perkins’ property would be taken unless the sale satisfies a social securities tax claim.

The trucks were confiscated from the York battery manufacturer last month because he refused to pay $105.36 in social security taxes, penalties and interest.

Today’s auction at the post office garage marked another round in the Perkins-versus-New Deal battle which began in when he went to jail for 18 days for defying the NRA. [He had apparently paid less than the 40¢/hour minimum wage set by that New Deal federal office. The Supreme Court later ruled the NRA was unconstitutional, and so the government abandoned its defense of the conviction against Perkins while he was appealing it.]

The 61-year-old former Cornell University football player, who also is in hot water with the State of Pennsylvania for non-payment of unemployment compensation taxes, said he would try to buy back his trucks.

Sale of the trucks to Perkins for less than the amount of the government’s claim, said Henry L. Haines, chief field deputy of the internal revenue office in Philadelphia, means that they will be seized again. If they go to another bidder and the claim remains unfulfilled, regulations provide that more of Perkins’ property be confiscated until the taxes and costs are paid in full.

On the other hand. Haines explained, Perkins can make a settlement before the hammer falls or can erase the claim by buying his trucks for a price equal to his unpaid taxes plus costs.

Since Federal agents took Perkins up on his challenge to “come and get it” [an earlier article had quoted him as saying “I ask the government if it has the courage to enforce this law.”] and seized the trucks , he has been delivering batteries in his son’s roadster.

The state plans to sue Perkins this week unless he pays $222.41 in job taxes — an expense he declares he “can’t afford.” Perkins employs only six or seven men.

In another article, Perkins explained:

“I certainly don’t intend to pay the State taxes. I haven’t made any net profits and can’t afford to pay them. My net earnings for were less than my employes’. … We should tax employers who lay off their employes. Don’t soak the man who gives his employes steady employment — at least the small business man. What is morally wrong is never politically right.”

Another newspaper quoted him as calling on “every self-respecting and oppressed employer in the state of Pennsylvania to join me in refusing to pay another cent in payroll taxes — come what may.”

Here’s another example, from :

Social Security “Immoral, Illegal”

Woman Editor Defies U.S. on Old Age Tax

Summit, Miss. — (U.P.) — A fiery woman editor and recent unsuccessful candidate for governor declared today she will not pay Social Security taxes and challenged the Federal Government to do something about it.

Mrs. Mary D. Cain, editor of the weekly Summit Sun, wrote an open letter to Secretary of the Treasury John Snyder, denouncing Social Security as “immoral and illegal.”

Mrs. Cain said she will refuse to pay the new self-employment tax on herself and also will not deduct Social Security payments from the salaries of employes.

“Pop your whip, Mr. Snyder, I’m ready,” she wrote. “Either confiscate my business or put me in prison.”

She said she hopes the government will imprison her for not paying the tax “because then the people of America will realize to what a pretty pass we have come in this country when one can be imprisoned or heavily fined for simply doing what has ever been considered the honorable, American way of living — taking care of one’s own old age.”

“The Social Security program, added to the equally iniquitous and confiscatory income tax program, is the hub around which the whole wheel of communism revolves in this country,

“I’ve had enough of the New Deal. I’m sick of the whole Truman administration. Pop your whip, Mr. Snyder, I am ready.”

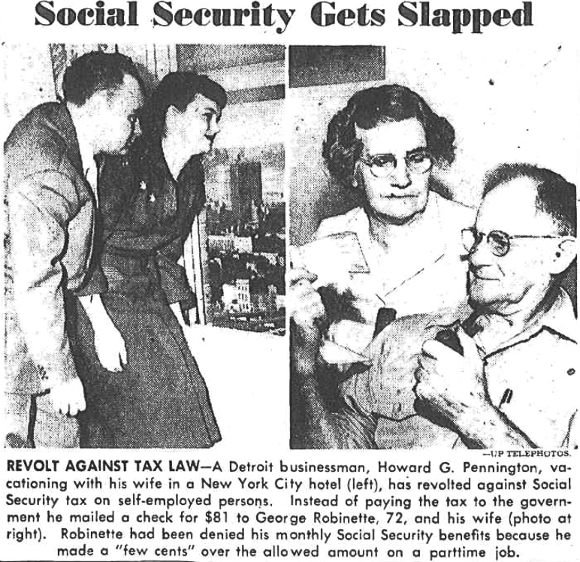

We’ve met Mary Cain before. But this article was accompanied by some photos and a caption about a social security tax resistance and redirection action I hadn’t heard about before:

It took me a while to find any more about this action, but I finally found this:

Money Owed U.S. Given To Oldster

Detroit, . — A one-man revolt against the government’s new social security tax on self-employed business men was waged today by Howard Pennington, partner in a wholesale tobacco and candy firm in suburban Lincoln Park.

Pennington wrote the internal revenue collector that he would not pay his $81 tax and that he had sent that amount of money to a 72-year-old pensioner in Ypsilanti, Mich. The pensioner, George Robinett, recently was deprived of three months of his social security pension, a total of $210, because he earned 62 cents more than the $50 monthly wage to which a pensioner is limited.

Pennington’s refusal was based on his contention that he would pay at least $3000 “for nothing” under the tax because he wouldn’t mismanage his business sufficiently to remain qualified to receive a pension in return. He said he objected to turning over his money “for waste by socialistic dreamers.”