This is the twenty-eighth in a series of posts about war tax resistance as it was reported in back issues of Gospel Herald, journal of the (Old) Mennonite Church.

When I hit in the archives it seemed to me that I started seeing a lot more mentions of how “our tax dollars” were financing this or that government-sponsored horror, but much less followup from there about how such a thing might lead one to resist paying. Maybe that was seen as an obvious corollary by then, or maybe some people had abandoned the idea of war tax resistance as impractical and had just become resigned to complaining. It’s hard to tell from the record.

That’s not to say there wasn’t war tax resistance content. Plenty of it. The “Taxes for Peace” war tax redirection fund, run by the Mennonite Central Committee’s (U.S.) Peace Section, announced it’s annual drive in the issue. The fund would be redirecting money to the Lancaster County (Pa.) Peacework Alternatives Project, and announced that they had redirected $4,600 to a project to aid victims of violence in Guatemala the previous year.

A curious story, “The parable of the taxpayers” by John F. Murray appeared in the . It was a sort of updating of the “parable of the talents” from the Bible. It included a character who was a war tax resister but the parable chided him for hiding his money away from the tax collector rather than spending it on good churchly stuff. Perhaps this indicates that this was one stereotype of war tax resisters — as miserly sorts — that was prevalent in Mennonite circles.

The emerging war tax resistance movement in Japan took the offensive in , according to this article:

A Mennonite pastor is among 22 Japanese tax resisters who have sued the government for what they say was an “unconstitutional” collection of their taxes in . The 22 are all members of Conscientious Objection to Military Tax (COMIT), and 12 of them are Christians — including Michio Ohno, a Mennonite pastor in Tokyo. The government action involved the seizing of the bank accounts of Ohno and two others. The 22 charge that Japan’s so-called Self-Defense Forces is a violation of the post-World War Ⅱ constitution, which forbids the country to have an army, navy, and air force. So, they charge, the collection of taxes for the military is also unconstitutional.

John K. Stoner promoted war tax resistance :

To pay or not to pay war taxes

Nine to five

by John K. Stoner

Members of the Mennonite Church in the United States contribute $9 to the federal government for military purposes for every $5 they contribute to the local church for the cause of Christ.

Nine to five is the proportion of military support to local church support. Nine to five is also a traditional eight-hour workday. The fruit of our labor is paying for the arms race.

The nine-to-five calculation is based on figures from the current Mennonite Yearbook, p. 190. The contributions given by U.S. Mennonite Church members through the congregational treasury in totaled $57,269,704. This figure does not include individual gifts that were not channeled through the congregation. The estimated military tax paid by the same people in was $105,800,000.

Stanley Kropf, churchwide agency finance secretary, estimates that the pretax income of Mennonite Church members in was $1,602,600,000. I have calculated a 12 percent tax rate paid on that income, with 55 percent of the taxes going to past and present military costs, including a portion of interest on the federal debt attributable to inflationary military spending. I believe that these figures are correct within a margin of 5–10 percent.

No great concern?

Maybe it isn’t a matter of great concern. Some say that the government is responsible for what it does with tax monies. We are not accountable.

Bernard Offen, a Jewish survivor of Auschwitz, thinks differently. His letter of war-tax protest came across my desk recently, and I share it as a stimulus to reflection on our war taxes in :

The guards at Auschwitz herded my father to the left and me to the right. I was a child. I never saw him again.

He was a good man. He was loyal, obedient, law-abiding. He paid his taxes. He was a Jew. He paid his taxes. He died in the concentration camp. He had paid his taxes.

My father didn’t know he was paying for barbed wire. For tattoo equipment. For concrete. For whips. For dogs. For cattle cars. For Zyklon B gas. For gas ovens. For his destruction. For the destruction of 6,000,000 Jews. For the destruction of 6,000,000 Jews. For the destruction, ultimately, of 50,000,000 people in World War Ⅱ.

In Auschwitz I was tattoo #B‒7815. In the United States I am an American citizen, taxpayer #370‒32‒6858. I am paying for a nuclear arms race. A nuclear arms race that is both homicidal and suicidal. It could end life for 5,000,000,000 people, five billion Jews. For now the whole world is Jewish and nuclear devices are the gas ovens for the planet. There is no longer a selection process such as I experienced at Auschwitz.

We are now one.

I am an American. I am loyal, obedient, law-abiding. I am afraid of the Internal Revenue Service. Who knows what power they have to charge me penalties and interest? To seize my property? To imprison me? After soul-searching and God-wrestling for several years, I have concluded that I am more afraid of what my government may do to me, mine, and the world with the money if I pay it… if I pay it.

I do believe in taxes for health, education, and the welfare of the public. While I do not agree with all the actions of my government, to go along with the nuclear arms race is suicidal. It threatens my life. It threatens the life of my family. It threatens the world.

I remember my father. I have learned from Auschwitz. I will not willingly contribute to the production of nuclear devices. They are more lethal than the gas Zyklon B, the gas that killed my father and countless others.

I am withholding 25 percent of my tax and forwarding it to a peace tax fund.

Offen gives permission to reproduce or publish his letter and says he may be contacted at Sonoma County Taxes for Peace, Box 563, Santa Rosa, CA 95402.

No simple answer. What is the answer to the war-tax dilemma? I offer no simple one. I simply identify a challenge to our faith which will not go away. And I think it is helpful to have some idea of how much money, and in what proportion, we are giving to the death machine.

St. Augustine said, “Hope has two sisters: Anger and courage.” Beautiful women, these, in an age of despair.

That prompted a letter to the editor from Lester L. Lind:

Thank you for printing the article by John Stoner, “Nine to Five”… It is good but uncomfortable for us to be reminded of our involvement in military and war-related activity. I wonder how much longer the Mennonite Church can remain so silent and still carry the distinction of being a peace church. In a democracy, silence gives consent. In light of Scripture, our history, and the present reality that Stoner points out, how can we Mennonites give our consent to spending so much for war?

Withholding federal income tax for conscience’ sake is still a lonely and often misunderstood act, even within the church. True, there are individuals and small segments of the Mennonite Church who have taken positions similar to the Stoners. But I long and pray for the time when such actions of civil disobedience will be strongly supported and encouraged by the majority of Mennonites.

A war tax redirection ceremony and tax day protest was covered in the issue:

Michigan group gives war-tax money to the poor.

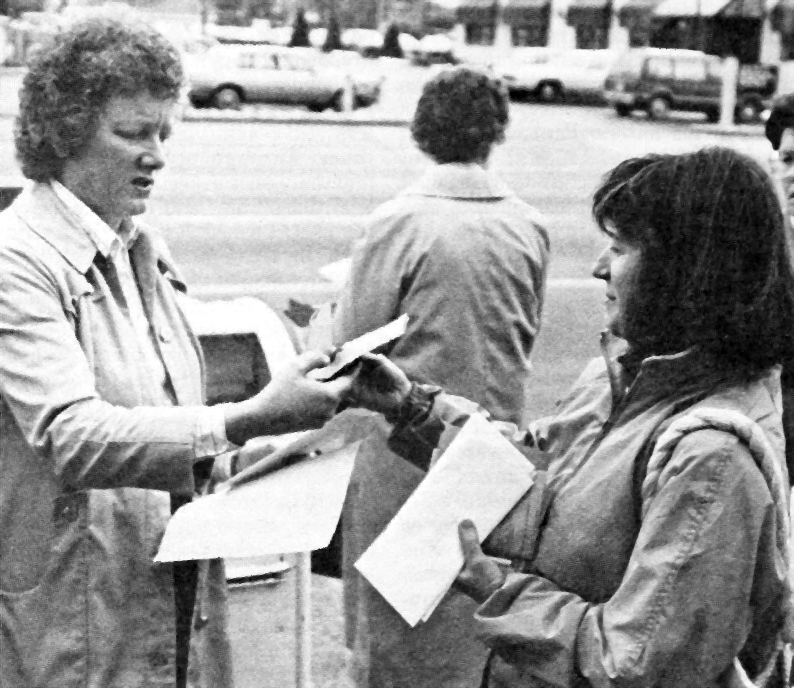

On the income-tax deadline of , a group of 11 people in Kalamazoo, Mich., called “Partners in Peace” gave a public witness to their beliefs in front of the post office. They mailed their income-tax returns minus the amount they calculate is used for military purposes — 50 percent.

Instead the group gave that amount — which together came to about $5,500 — to five local agencies that assist the needy. Here Partners for Peace member Karen Small gives a check to Marcia Jackson of Loaves and Fishes.

The group, which includes Mennonites, also conducted a short worship service with singing, prayer, and testimonies by several participants. Onlookers were given printed statements and pens with the inscription, “If you pray for peace, should you pay for war?”

This is the second year the public witness has been conducted. Winfred Stoltzfus, a Mennonite doctor who is a member of the group, said he and others are being “harassed” by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, which is seizing bank accounts and portions of their paychecks.

The existence of a mutual aid fund for war tax resisters was made known to readers of the issue:

“Even if you are not a war tax resister, you can help those who are,” say a group of Christians who operate the Tax Resisters Penalty Fund. Based in North Manchester, Ind., it helps resisters when they suffer financial loss through the seizure of penalties and interest by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service. The fund, started in as a project of the local chapter of Fellowship of Reconciliation, is currently trying to broaden its base of support because of the increasing number of requests for assistance. More information is available from the North Manchester Fellowship of Reconciliation…

While war tax resistance seemed mostly a U.S. phenomenon during the Vietnam War era (and this led to some chagrin when Canadian Mennonites felt like they were being dragged into disputes about it), Canadians were also getting in on the act by this time ():

Canadian war-tax resisters hold first national conference

Conscience Canada, a Victoria, B.C.-based organization objecting to Canadian military taxes, held its first national conference recently. Several participants reported that they sent the military portion of their taxes to Peace Tax Fund — a trust account administered by Conscience Canada which is not approved by the government.

Member of Parliament James Manley told the participants how they could be more effective in lobbying their MPs. Motions favoring peace tax legislation were introduced in the House of Commons by Manley in and and by MP Simon De Jong in .

Reporting on war-tax resistance in the United States, Robert Hull, a Mennonite who chairs the Washington, D.C.-based National Campaign for a Peace Tax Fund, said his group has enlisted 55 representatives and four senators as sponsors of peace tax legislation in the U.S. Congress.

“Conscience Canada is part of a movement in 17 countries, from Finland and Spain to Australia and New Zealand,” said Edith Adamson, the organization’s coordinator.

And the issue noted:

Study packet on militarism in Canada from Mennonite Central Committee Canada. It includes pamphlets, articles, and a fact sheet. The packet helps Canadians struggling to discern a faithful Christian response to militarism, including the issue of whether or not to pay war taxes. It is available for a suggested donation of $3 from Information Services at MCC Canada…

David Charles wrote a commentary for the issue in which he went on at length about the horror of nuclear war and said “Some have even come to recognize our complicity in the situation through silence and the payment of war taxes.” And: “Our continued silence to a government that is not merely content to collect tax but is mortgaging the entire country to pursue a ridiculous ambition is conveying a message of acceptance.” But his suggested response was hilariously pathetic:

We can write on the bottom of our tax returns that our money is to be used to build peace, not more arms.

In the issue, Edgar Metzler wrestled with “Following Christ in a militaristic world” and tried to nudge the Mennonite Church toward a bold decision:

For an increasing number of Christians the conscription of their taxes for military purposes is becoming a problem of conscience as clear as the conscription of their bodies for military service. The question will not fade away. Are the excuses offered by Nazi collaborators or Iran-contra conspirators that someone else is making the decisions that much different than washing our hands of responsibility for how the state uses the resources God has given us?

Challenge and action.

The study suggested by MCC and the militarism resolution — “Growing in Stewardship and Witness in a Militaristic World” — which will be considered by the General Assembly at Purdue arose directly out of the struggle of conscience about war taxes by some members of the church. The proposed resolution is intended to alert us to the broad scope of this challenge and suggest appropriate actions.

The decision, bold or not, would be adopted at the Mennonite Church General Assembly on : “Growing in stewardship and witness in a militaristic world” Here are some excerpts that concern taxes:

Let us expand our support for proposed Peace Tax Fund legislation in both the United States and Canada, recognizing that legal recognition of conscientious objection to payment of taxes destined for military use will require the same patient persistence which resulted in legal recognition of conscientious objection to military service.

Let us prayerfully examine the practice of church organizations withholding and transmitting income taxes of church employees who themselves are conscientiously unable to pay taxes for military use. As part of that effort, we will participate in a conference planned for for Mennonite, Brethren, and Quaker employers to share their experiences relating to tax withholding and conscience and to develop a strategy for relief of this ethical dilemma.

Let us continue to support those whose conscience prevents them from paying taxes destined for military use or from registering with the U.S. Selective Service System.

A report from the conference, carried in the issue, carried the ominous quote “Personally, I think the Peace Tax Fund is a way out of this” as a way of excusing why the Mennonite Church seemed to be waffling rather than taking any committed stand:

A statement on “Growing in Stewardship and Witness in a Militaristic World” was approved more quickly. It offers suggestions to congregations for ways to counter the increasingly pervasive “evil” of militarism in North America and around the world.

Ed Metzler, who presented the statement, said one of the best ways Mennonites can oppose militarism today is by supporting the campaign for “Peace Tax Fund” legislation in both the United States and Canada. Metzler, who is peace and social concerns secretary at Mennonite Board of Congregational Ministries, said this would permit conscientious objection to war taxes in the same way that Mennonites and others won the right to conscientious objection to war. He called to the podium the executive director of the campaign in the U.S. — Marian Franz, a Mennonite. “Conscience is contagious,” she said, “and peace concerns are spreading far beyond the historic peace churches.”

Approval of the statement did not end the discussion on militarism. Especially after Mennonite Board of Missions president Paul Gingrich reminded the delegates that his agency is still waiting to hear what it is supposed to do about employees who request that taxes not be withheld from their paychecks so that they can resist war taxes. “I wish this body would act on this,” he said.

Metzler agreed, pointing out that the Mennonite Church General Board “ducked the issue” by calling for a general statement on militarism. “We wish the issue would go away,” he said, “but it won’t.” Moderator-Elect Lebold defended General Board inaction, noting that the church is deeply divided on the subject. “Personally, I think the Peace Tax Fund is a way out of this,” he said.

Nondelegate Ray Gingerich, an Eastern Mennonite College professor who is a war tax resister, challenged the notion of having to wait on the government to make legal a matter of conscience. Many delegates seemed to agree, and by majority vote, they instructed General Board to take immediate action on tax withholding and give a clear answer to MBM and other agencies seeking guidance.

The issue carried an interview with Thomas L. Shaffer (a Catholic law professor). Excerpt:

- Q:

- Are you a pacifist?

- A:

- Well, I think so. It is an odd question for a 53-year-old person because nobody’s asking me to wreak violence on anybody else. We are all very fortunate to have that little dialogue about paying over the coin to Caesar because otherwise we 53-year-olds, if we thought of being pacifists, would have to think of financing nuclear weapons. I guess that little dialogue lets us out, or at least in some people’s minds it does. But I figure that by now the taxes I paid have bought a lot of destructive weaponry, if I am paying my share.

The Church of the Brethren (Anabaptist cousins of the Mennonites) also held their annual conference. The issue reported:

An agenda item on “taxation for war” prompted little debate, since a study committee said the church has written enough about war-tax resistance, and that it is time for members to study seriously what has been written.

That issue also carried this news:

Church asks forgiveness of antiwar activist defrocked 25 years ago

The Presbyterian Church (USA) has publicly asked the forgiveness of an 81-year-old Cincinnati minister who was defrocked by a regional church body 25 years ago for his antiwar activism. Maurice McCrackin, pastor of the nondenominational Community Church of Cincinnati, was deposed from the ministry by the Cincinnati Presbytery in after he refused to pay the portion of his income taxes that would go for military spending. Meeting in Biloxi, Miss., the denomination’s highest governing body, the General Assembly, formally confessed error in removing McCrackin from the ministry and endorsed an action taken in by the Presbytery of Cincinnati restoring him to clergy status.

The attempts to get the Mennonite Church to take risks on behalf of war tax resisters got the goat of of Elmer S. Yoder, who wrote the following for the issue — again suggesting the Peace Tax Fund as a way of sidelining the problem:

Whose conscience is to be respected?

The concluding appeal by a delegate at Purdue to “respect the individual conscience” in regard to church institutions not withholding “war taxes” failed to address a key question. The appeal sounded simple and persuasive, on the surface, but it is much more complex and far-reaching. Whose conscience is to be respected? The conscience of the individual employee of an institution or the collective conscience of a board of directors, or perhaps even General Assembly?

The corporation is a legal entity and owes its continued existence to statutory provisions. The centralized management of the corporation can and does express the collective conscience of the institution. Our major church institutions are incorporated and directed by boards. The directors have been charged with the optimum operation of the institutions. The institutions (corporations) are faced with options different from those of an individual in respect to a refusal to pay the tax in question.

An individual refusing to pay what he considers is the war tax would be confronted by an agency of the government. The result might be the placing of some financial restrictions upon him, or additional legal action, such as seizure of property, or in extreme cases, imprisonment. Noncompliance by a church corporation would almost certainly result in governmental measures amounting to a substantial loss of freedom. This loss could well include its legal base to perform the objectives and purposes included in its charter and given by the Mennonite Church.

An individual Christian respecting the conscience of a war-tax resister suffers no detrimental consequences legally. A trustee of a church institution is in a completely different situation. By consenting with fellow trustees not to withhold the tax in question, he and the trustees are inviting various restrictions on the institution via legal action.

Legal alternatives of not withholding the war tax have been researched thoroughly by the General Conference Mennonite Church, without finding any legal recourse. This means that trustees of church institutions would engage in civil disobedience by not withholding from any employee’s salary the part of the tax he protests, but in addition, would push the institution into a morass of legal restrictions and extended court procedures that would severely hamper the operation of the institution or drain its resources through protracted legal fees.

This is not a plea to act only on the basis of potential consequences. The call to faithfulness supersedes consequences. But faithfulness in great diversity of understanding, such as the war tax issue and the legal consequences, is difficult to achieve. It is not in the interests of brotherhood to create or foster an institutional versus individual conflict, but neither is it proper or ethical to evade the issue of an institutional conscience. In church institutions that conscience is molded by the larger brotherhood and those directly charged for the operation of the institutions — the trustees.

Nearly 100 years ago, the Mennonite Church began forming institutions (corporations) to carry out more effectively its tasks of nurture, education, and evangelism. The institutions have served well and have contributed in many ways to the mission of the Mennonite Church. Shall this servant role of the institutions continue? Trustees of the institutions can, by openly defying the law over an issue on which such a diversity of opinion exists within the Mennonite Church, shackle the institutions, rather than performing as stewards.

Perhaps the time is coming, in the United States, when the church may again need to preach, to teach, and to evangelize without the legal entity of the corporation. Perhaps there again will be the time for the fabled school with the professor on one end of a log and the student on the other. The church corporation, which makes possible educating larger numbers, would be conspicuously absent, because of legal ramifications. But, in my opinion, that time is not yet.

Perhaps, rather than urging a course of action which would eventually eliminate faculty and staff positions in the institutions, the energies and efforts devoted to this should be channeled into making possible a legal alternative, such as the Peace Tax Fund. Devoting one’s energies to making it possible for larger numbers to step out and take advantage of the Peace Tax Fund certainly would be preferred to potentially reducing the church institutions into ineffectiveness.

The “New Call to Peacemaking” initiative was still active, but seemed to be deemphasizing war tax resistance. It is not until the penultimate paragraph of this story that war tax issues are mentioned:

Some of New Call’s limited resources do go to renewing the vision within the historic peace churches. In a conference will be cosponsored with the Quaker War Tax Concerns Committee on the challenge to church organizations from employees requesting their federal taxes not be withheld so they can exercise their conscience in relation to war taxes.

This letter to the editor, from Edgar Metzler, appeared in the issue:

Thank you for sharing Ike Glick’s courageous decision of conscience to resign from a company that might be involved in military contracts (). All of us in North America are inextricably involved in an economy addicted to huge military expenditures. Ike’s conscience challenges especially all of us who think that the taxes we pay to build weapons of war are something for which we have no responsibility. Our stewardship teachings tell us it is God’s money. How we use that resource surely must be a matter of conscience as much as the way we use our God-given talents in our occupations.