War tax resistance in the Friends Journal in

Mentions of war tax resistance in the Friends Journal in tended to either look back fondly at resisters of the past, or to look forward to a time when a peace tax fund law would magically dispel the dilemma of praying for peace while paying for war.

Paul Zorn’s article from which cast a skeptical eye on the value of Quaker war tax resistance picked up some dissent in the issue.

- Merrill Barnebey felt that Zorn “fails to fully grasp the significance and timeliness of tax resistance. For one thing… Quakers who do not protest war taxes are establishing a credibility gap.” He also felt that tax resistance helped to pressure Congress to pass the Peace Tax Fund bill.

Also in the issue, Elwood Cronk told a story of how a meeting that was involved “an ecumenical effort to establish a food cupboard” reacted with hostility to war tax resisters in their midst:

A couple, wishing to make a war tax witness to IRS, presented the meeting with a check for $100, the portion of tax they were withholding. Their accompanying letter stated they felt this was an appropriate gift to the meeting, in view of federal budget cuts in social services. They asked that the money be accepted as a start-up fund for the food cupboard.

…One person walked out, another questioned their motivation, and the meeting declined the check. The one positive thing which did happen occurred the next Sunday. A member of the adult class proposed that war taxes be discussed that day.

An obituary notice for Ronald E. Chinn in the issue noted that Chinn “helped found a university endowment fund for lectures on peace issues, using money withheld by Alaskan war tax resisters.”

In the issue, Kenneth Miller wrote in to share the exciting news that, after persistent lobbying and lots of hard work, Peace Tax Fund bill supporters had managed to convince Nancy Pelosi to cosponsor the bill. (Pelosi at the time was just starting her career as a U.S. Representative. She became Speaker of the House in and is currently the Minority Leader there. She is no longer a cosponsor of the present peace tax fund scheme.)

The issue announced a new edition of Conscience Canada’s book The First Freedom which “reviews the legal history of conscientious objection for taxpayers in Canada and provides an overview of new charter decisions and recent court cases.”

“Honoring employees’ requests not to withhold the military portion of their federal income tax is now the official policy of Baltimore Yearly Meeting,” began a short piece in the issue. “In taking the action as requested by individual employees, the yearly meeting emphasized its history of supporting military tax resistance through urging passage of the U.S. Peace Tax Fund Bill, as well as supporting other religious organizations involved in military tax refusal. In , the yearly meeting minuted that it ‘stands in loving support of those moved by conscience to witness against making payments for war and preparation for war, including those who refuse to pay military taxes voluntarily.’ ”

D.H. Rubenstein penned an op-ed piece for the issue in which he reviewed the difficulty that Friends and Friends Meetings had with the issue of war taxes, and held out hope that Congress would throw Quakers a rope by passing some sort of Peace Tax Fund plan. Excerpts:

It is a perplexing problem to be a citizen of a country whose policies include militarism and war as a means of relating to other nations and at the same time be a member of a religious society whose traditions are contrary to such policy. Conscientious objection to military service is now accepted. But what about paying taxes to support war and militarism?

When Friends gather to consider this dilemma it is often expressed that each person must decide on the basis of the individual’s own leading how to resolve the claims of conscience between being a law-abiding citizen and a faithful Friend. Rarely is unity achieved.

Another entanglement is the matter of Friends organizations and their involvement in the payment of war taxes. One of the key questions is whether or not such organizations have a “corporate conscience” and a responsibility to act in accord with traditional Quaker witness and its historic peace testimony.

Relatively few individual Friends are prepared to refuse to pay war taxes — an illegal, punishable offense — and suffer the consequences of such refusal. How could they, therefore, adopt a policy which would make the corporate body and its officers liable for such consequences? In other words, is it fair for me to expect a higher order of morality from the corporate body than from its individual members?

(Please consider a slight digression. Is it fair to assume that if a legal way of not paying war taxes existed we would take that option? If the answer is yes, we should commit ourselves to the promotion and support of the Peace Tax Fund Bill… whose aim is to provide that specific option.)

Friends are staunch in their belief that that of God within each individual should be the guiding light by which life is lived. Quaker experience, however, has verified the need for the admonition of Paul, who cautioned believers in Rome, “Do not be conformed to this world…” (Rom. 12:2). The light of the Spirit is available to each one of us: its accessibility without distortion by our own willfulness or societal influences is a hazard we do not always recognize. It is this of which Paul reminds us. This is one of the reasons our corporate wisdom has established that although the Light is available to each of us, it is essential we gather together for communal seeking and sharing in order that our findings be validated in the group, which is less likely to be misled than the individual.

If we are unable to discern God’s leading, that is a very different matter than God saying no. It means further seeking is required until clarity is achieved. It does not mean no action is required. We need to recognize that at present we are involved in actions which by implication indicate Friends support and believe in militarism and war. This is what our present tax paying and tax collecting actions declare.

What do we believe? Must our apparent schizophrenia on this subject be a permanent state, or can we thresh our way out of it?

The Peace Tax Fund would create a legal alternative. The enactment of an economic conversion bill (several now in Congress) could provide for a specific application of CO tax funds to a basic civilian need and away from the military-industrial behemoth. Our energies applied to the support and adoption of these two legislative proposals might supply some ameliorative therapy for our dilemma while we pursue some serious threshing.

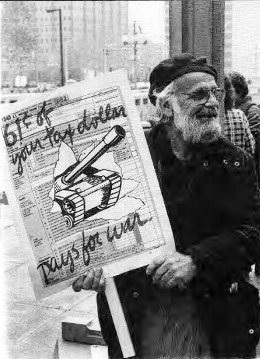

That same issue included a profile of George & Lillian Willoughby that included a section on their tax resistance:

Working for Peace, not Paying for War

Another significant protest in the Willoughbys’ lives has been their ongoing tax resistance. “I object to taxes that go completely out of my hands and have no connection to me — that are supporting things I cannot tolerate, such as bombs and nuclear energy,” Lillian says.

After years of refusal to pay their federal telephone tax, IRS officers seized the Willoughbys’ Volkswagen to collect the $100 they owed. But the Willoughbys’ many friends raised more than a thousand dollars through a “peace bond” mailing so they could submit the winning bid and recover the car. The extra funds were donated to the Philadelphia War Tax Resistance Fund.

“One IRS official complained,” George recalls, “ ‘Here we seize your car to raise money for IRS, and you are using it to raise money for your cause!’ ” After that incident, there were no more seizures of automobiles of tax resisters in the Philadelphia area for the next nine years, the Willoughbys say.

Explaining their tax witness, Lillian notes, “Some sacrifice is involved, and not everyone can do it.” For George, it is a matter of integrity and empowerment. “Tax resistance is something I can do to withdraw support from the government,” he says. “Why should I give them money to do evil things I wouldn’t do myself?”