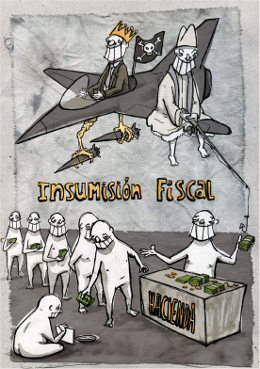

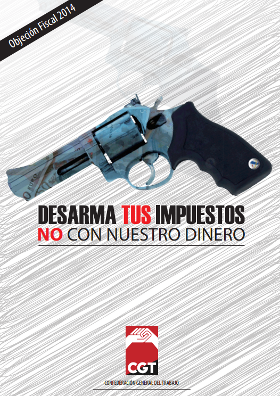

There has been a lot of talk of tax resistance in Spain lately, both from an energetic war tax resistance movement and from a new environmental / social justice tax resistance campaign focusing on the skulduggery of the Spanish government’s responding to the economic crisis with corporate bailouts.

1.

Everyone knows that Spring customarily brings the flowering of the gardens, the heat of love, and the obligation to submit your tax returns — all equally arousing things, though in different erogenous zones.

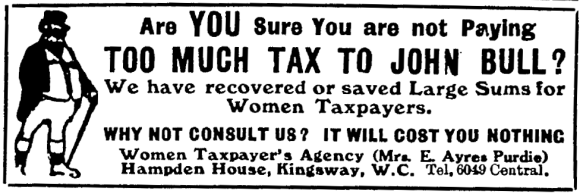

For some years at this time there have also tended to be some social organizations spreading their campaigns for so-called tax resistance, simultaneously with the tenacious clerical propaganda for good Catholics to mark the box on their tax returns next to the Catholic Church.

The comparison is not an idle one, for we see that this and the other campaign agree on the same economic formula, a formula that is in my opinion alarmingly reactionary, even in the view that it is with the best, most altruistic and noble intentions in the world.

The way in which it tries to encourage citizens to object via taxes, and the method that it proposes for doing so, may vary in some details, depending on the organization or the social platform in question, but always they repeat some elemental features.

The manifest and indisputable injustice is alleged in which the state always dedicates fewer resources to sustaining basic public health and education services, or to the aid of the most disadvantaged social classes, directing instead exorbitant amounts to armaments, heavily polluting industries, or to various other ends damaging to the community.

Most common is tax resistance that is justified in protest against military spending, but this is not the only possibility.

This year, for example, in particular: the opposition to the transfer of billions in public money to banks and the real estate sector, among other principle causes of the crisis, which without a doubt constitutes an obscenity.

The concrete objection is to refuse to pay, when submitting the income tax return, a particular amount of money that beforehand will be redirected to some social organization that struggles for peace, for social justice, or for conservation of nature.

The amount usually is small, fixed, calculated as a percentage of the tax or freely determined by the “objector.”

As a fixed amount, 84 euros has been proposed, which is meant to symbolize the 84 most impoverished countries on the planet.

And the choice of a percentage of the tax is singularly comical, because it supposes that in general those who owe more taxes are freed from paying more to the Treasury, or, seen another way, that the right to resist grows in proportion to the wealth of the taxpayer — a strange notion of economic justice to be promoted by leftist groups.

The most common formula for reflecting this reduction we withhold from our taxes consists in simply recording it in the blank box of miscellaneous deductions or subtracting it from the tax owed.

In one way or another, if what is intended is to express a protest, it must be sufficiently visible, not camouflaged in some concept that could be easily overlooked.

It is recommended for this reason that the Tax Administration Agency be contacted with a written statement, claiming that we deduct the money from our return in order to reduce military spending (or from nuclear plants, or public bank bailouts, or all at the same time), and that a receipt is attached showing our redirection to a social organization or project that we have chosen.

Let it be clear that I am in heartfelt agreement with the idea of fighting for public funds to be allocated to guarantee quality social services for all citizens and to reduce inequality and fight injustice.

The question is whether tax resistance helps these objectives, as such, and if not, on the other hand, what other harmful side effects might follow.

After submitting our tax return with the corresponding act of civil disobedience, two things may happen.

It is to be expected that the Tax Agency will issue its own return and charge us for what we failed to pay.

For this eventuality, the promoters of resistance ask us to comfort ourselves until the end with the idea of converting each such letter into a new opportunity to protest (a protest, indeed, that will stop in the hands of some bureaucrat who typically ignores our pleas for social justice, and who will simply dismiss our claims according to the stipulated procedure).

It will be useful to clarify to the potential resisters of good faith how much more influence they can have with their protest letters the more money they owe.

Above all, one should note that the social advocacy organizations for tax resistance usually include themselves among the beneficiaries of the redirected money and that it is obligatory to observe a minimum of honesty with our purveyors.

In any case, in the best scenario, we will be charged the debt plus interest.

Although one thing to know, having announced our unequivocal will to not submit part of the tax, knowing that legally we have to, the General Tax Law does without a doubt cover such a case with sanctions for non-compliance.

On the other hand this usually does not come to pass.

It happens in no few occasions, however, that the Tax Agency makes no complaint.

In an article published recently in favor of resistance, I read the pious explanation that the motive for such indulgence might be that small amounts are not detected, or because of bureaucratic negligence or even “complicity.”

In reality, things don’t work like this.

In practically all tax returns, missing income is detected by computer (except for sneaky tax shelters that show no evidence of irregularity, a practice that would contradict the intention to use the tax resistance as a public protest).

And if once discovered but not charged, this is likely because the debt is so low that the administrative procedures to force payment would cost more, or because, given the growing scarcity of personnel, the Tax Agency offices are concentrating on larger debts.

I feel, indeed, this betrays a trust in the existence of bureaucrats sympathetic to our cause, but I can perhaps dream that there are many willing to risk their jobs overlooking procedures that are strictly regulated, concerning things in which each decision remains recorded and personally keyed in databases, and that are accounted with a multitude of controls, as well as being audited with relative frequency.

From one motive or another, often we settle with ourselves and pay less than we owe to the Treasury.

What have we achieved with this?

Only to reduce, by much or little, the amount of State revenue.

After which, the government will allocate a sum of what is collected to such expenses as it decides, and not to those which objectors have demanded, and, as for having to reduce some part, it will be in that which seems good.

A government that realizes a conservative economic policy — and, frankly, I do not hope for another type of government, at least in the coming years — will tend just to sacrifice social spending, and, in each case, will always meet their obligations to the army, to NATO, to the large corporations, and to the banks.

If to do so one has to sacrifice spending on health or education, so be it.

To be successful, our good-intentioned tax resisters might take note of the segments of society least protected by underfunded public services.

We have given our money to committed social organizations, it is true.

But these, as diligent as they are, will always constitute a private safety net.

That is to say that we may be provoking a transfer of resources from universal, free, public services to private entities.

This is a form of privatization, or, in other words, transforming the exercise of rights that we have demanded from the powers that be, into charity dependent on good samaritans.

James Petras has given us some excellent texts on this, not much to the taste, of course, of certain NGOs.

2.

One might think, however, that although tax resistance lacks any effect on revenue and public spending or even has somewhat undesirable effects, it might, to compensate, set off a social echo of rebellion against the patent injustices of the capitalist state.

But an examination of the results of all the tax resistance campaigns of the past years would have to have disillusioned the proponents on this point by now.

Nobody would have learned that such campaigns are carried out if not for the publicity that the same promoting social organizations give.

And, of course, the letters sent to the Tax Agency have absolutely no effect.

In general, bureaucrats pass over such arguments of a political nature when resolving appeals; at most, they remember it as an anecdote of their work.

The mythical vision of dozens of senior Administration officials terrorized by the exemplary valor of tax rebellion is a puerility that has nothing to do with the real world.

However, if the mere exercise of tax resistance is not significant or symbolic, the spread of the campaigns may serve up to the people a vision of taxes that has a surprising neoliberal resonance.

To begin, we have to question if it is very leftist, or even progressive, to claim the right of every citizen to decide individually what the state must do with the revenue from their taxes.

For to go even further: if we imagine a society that has superseded capitalism — socialist, communist, or libertarian — do we proclaim as a right for every person to dictate to the community the particular destination of their contribution?

Is this what the hell they mean when they allude to the objective of making every citizen “master of his income tax?”

Of what character of economic democracy are we thinking — the same as Milton Friedman and Hayek?

Doesn’t it address the collective management of the wealth of society?

Or am I old-fashioned?

To what point has the destruction of economic thinking reached that the left approaches these matters without a hint of doubt remaining?

Basically, fundamentally, what the partisans of resistance claim is the same as what serves the Catholic Church when it claims a slice of the income tax, as I said at the start.

The Episcopal Conference and the denominational Spanish state offer fervent citizens the opportunity to, in conscience, direct a percentage of their tax contribution to the unpaid pastoral work of don Rouco Varela.

And the partisans of resistance claim that the same possibility exists for antimilitarists or for those who hate the looting of the country at the hands of the bankers.

In those last two groups, I include myself.

The problem is that, when someone asserts a political right with universal character, it must take into account that not all of the citizens are going to make the same use of it, and admit, nevertheless, that any use will be legitimate.

Many of us will object to military spending and will redirect our portion of savings to progressive organizations, but others will want to subtract what is invested in the public health to practice abortions with dignity and security for women, or from unemployment payments, or will even desire for that military expenses increase, as showing patriotism can also be a subject of conscience.

Who will decide, and with what criteria, how far the conscience of each one can reach?

And since Emilio Botín is just as much a citizen as us, he will be granted the corresponding right to object, and not only that — if he decides to use the formula of a percentage of his tax, his right will be infinitely larger than that of his gardener.

Consistent with individualism as the model of society that underlies the acceptance of tax resistance, is the individualism of resistance as a civil rights issue in which the right to object is recognized as the Law.

The means are adjusted faithfully to the end proposed in this case, as what happened with the first Jesuits.

I mean to say that, in the current configuration of the income tax in our country, tax resistance as protest can only be an act eminently individual and moreover elite, or at least not equal for everyone.

It is a fiction that we pay our income tax at the moment of presenting our tax return; this is not so.

In reality, in the months of May and June the only thing that we do is submit to the Treasury a final accounting of what we have been paying over the past year for all of our income.

Salaried workers have paid their tax every month via the tax withholding that has been taken from their pay.

And small business owners and contractors make quarterly payments to account for what they have self-assessed in each period.

It is very difficult to practice tax resistance if one’s tax return comes back with a refund; but that it comes back with a refund doesn’t mean that one hasn’t paid ones income tax, but that in the final balance more was contributed to the Treasury and one asks that it refund the surplus.

Even if one is self-employed and files and has no right to a refund — a situation in which we find each year thousands of citizens, incidentally those with the lowest incomes — still objection is entirely impossible, despite, as with the previous case, that one has paid ones taxes religiously.

Not to mention the poorest citizens, unemployed, retired, or social outcasts, whose taxes, or absolute lack of them, they do not give or have withheld, who do not pay income tax but many other sales taxes far more unjust than the income tax, each time they buy bread, board the bus, or eat soup, from which they are not given benefits.

All these thousands of people remain excluded from the possibility of tax resistance.

Which is to say, we speak of a “right” that business, individual or corporate, can exercise with the greatest of ease, but that salaried employees, retirees, and the unemployed will find very difficult if not impossible.

In olden times, a right of this nature was called privilege.

We are to believe in the sincerity of the social organizations that assert the right to object, but the truth is that what they ask for is an economic option that can be enjoyed principally by the upper classes, in which I don’t find many enthusiasts for world peace, or proponents of reduction in military spending, or those furious about public money used for bank bailouts.

In certain educational pamphlets from the promoters of tax resistance are proposed resolutions to this problem in the form of the curious suggestion that those who don’t submit a tax return instead send letters asking for the recognition of the right to object.

Very elegant: that the poor may be in solidarity with our responsible economic action as peaceful middle-class citizens.

Also propose that, along with everything else, they come together with us in defraying the interest on the tax debt if the Tax Agency reclaims it from us.

This, in order that they may feel they too have accomplished something, you see.

It’s very significant, for that matter, that the objection proposed happens to concern the income tax, one of the few taxes in our country — and almost the only one — that preserves some trace of progressivity, although increasingly more limited with each successive reactionary tax reform approved in these two decades by the People’s Party governments along with those of the Socialist Party.

At least since Marx and Engels included the requirement of “strong progressive taxation” in one of the ten major proposals for social transformation in the Communist Manifesto, the labor movement has attached great importance to the existence of high and very progressive income taxes in order to achieve social justice.

Why not, for example, a social mobilization against paying VAT on the purchase of food and other articles of crucial necessity?

Why not search for solidarity with small businesses in performing symbolic actions of sale without VAT?

It’s been about a century since Rosa Luxemburg wrote, in her work The Accumulation of Capital, a concise but visionary chapter showing the social and economic relation of the revenue from indirect and sales taxes with militarism.

The artificial increase of prices that provoke consumption taxes will cause a diversion of productive resources to one sector, the military, in which big business can solve its problems of insufficient markets by guaranteeing demand via political decisions of the state and transforming war itself into a specific region for accumulation.

Rosa Luxemburg offered data that give suspicion that this was what happened in the years immediately before the outbreak of the first world war.

Maybe it would be better to reflect on the reactionary tax reforms and today’s wars and to see if we can do something about it, if we want to, as antimilitarists, if we are to be taken seriously.

3.

I will acknowledge, in conclusion, that temperamentally I am very skeptical about proposals for what is called conscientious objection.

I have never proposed as my principal goal for my social action to bring peace to my conscience but to change reality to make it less odious.

I don’t want that I should be aloof from injustice, but that injustice not be committed.

While I remain alive, I can’t stand aside.

I don’t aspire that what I pay as my income tax does not go to military spending or to aid for bankers and speculators, but that military spending not increase and that aid not be given to bankers and speculators.

And neither do I seek after a society in which I have the right to decide the destiny of my contributions to the community.

My ideal is a society in which everyone and all who create the common wealth decide collectively how to manage it, in order to make true the principle of “from each according to his ability and to each according to his need.”

That would only be viable if it destroys capitalism, clearly, and if the capitalist state is transformed into a network of people’s councils that allow for every public decision to be adopted in a democratic and free manner by all citizens.

Those who share a similar ideal, though it be far off, have to agree at least that the actions that we take to achieve it have to be essentially collective and to move towards it and not in the opposite direction.

In the daily struggle, the forms of intervention can be many.

With a simple act of joining some fifty people at the Tax Agency in Madrid on the first day of tax season to protest against the wars and the complicity of the state with the looters of the country, it is possible to appear on all of the televisions and to make an impact on public opinion much greater than all the tax resistance campaigns.

On occasion it has been done.

The most profound and stable way — not detracting from the organization for a citizen’s movement to demand a just and progressive tax system, that which includes a recognized principle in Article 31 of the Constitution of 1978, stubbornly flouted with all the others that don’t suit the masters of the nation.

It is not very hard to explain to the citizenry the intolerable injustice of a dual-track income tax, in which one pays much more on earned income then on income from capital, or how the progressivity of taxation has been forcibly reduced in the past decades.

We must denounce those who benefit from the suppression of taxes on capital and the constant rebates of corporate taxes, and unmask the land-owners who again requested raising the VAT rates.

We tend to think that taxes are too dry a subject to organize social movements around, even though they constitute the backbone that sustains the set of social services before which privatization revolts us with reason.

With the actions of the struggle can coexist on occasion, of course, the civic refusal to pay certain taxes, either because they are unjust or because in extreme situations we decide to break with any variety of collaboration with the state and face the risk of receiving the corresponding punishment.

In this last consists the true civil disobedience, that we ought never to trivialize because it is something too serious.

I recall from the novelist Norman Mailer in his book The Armies of the Night, that the movement against the Vietnam War in the United States included, as a gesture of disobedience in solidarity with the burning of draft cards, a refusal of taxes.

The idea was to challenge the state and declare oneself in complete rebellion before it until the withdrawal from Vietnam and the end of the murder of innocents.

In the United States tax system, an action like this could be very visible because, unlike in our own in which the public administration concentrates its measures on collecting tax debts and the amount of tax crime is very high, there the consequences of not paying usually means winding up in jail.

In such a way, authentic acts of tax rebellion are always treated, and not merely objection that aspires to be recognized by the system as a peaceful variety.

It has nothing to do with some ridiculous poseur in the style of the bandit Fendetestas in El Bosque Animado.

Nobody can protest against imperialism and the massive crimes of the system and then merely be satisfied with pilfering small change from the purse.

When certain citizens have committed radical acts of civil disobedience, of deep ethical and political significance, they have been able to run grave personal risks if there existed an energetic, organized movement that supported them and even had sufficient strength to challenge power.

It is evident that today is not the point at which such western societies can be found, although with the indecency and the extent of the robbery, in a country with more than four million unemployed, one would think that we would live over a social volcano.

However, this does not have to paralyze us.

How have we not put into place a broad-based campaign to propose to people that they pull their savings from the banks?

Something that would be entirely legal, but that would truly shake the pillars of the system and that would probably stun more than one, even should we not bring many people on board right away.

If we’re talking about civic opposition, with effective measures, to the delivering of billions of public money to Botín, let’s let him clear from the government the money that they have given, we are going to withdraw.

How have occupation actions not spread to bank branches?

In a meeting of social movements in 2006 at Complutense University in Madrid, economist Fernando Urruticoechea proposed encouraging property owners to sell, in order to stimulate the replacement of home ownership for renting, but also to cause a collapse in the housing market in order to unblock the infernal and corrupt economic platform that churned our national capitalism.

If memory serves, among the social organizations that today make audacious apostleship for tax resistance are those that did not look kindly on this initiative.

There are many ways to oppose the iniquities of the world, many, save that of making a virtue of necessity and hiding our failures under the versatility of private conscience.

All of this has mostly confirmed for me that liberals are annoying the whole world over.

That’s probably too hasty.

Rodríguez and I just don’t start with the same assumptions is all.

If I believed, as he does, that people have a duty to contribute to the public good (as defined by whoever happens to be making decisions for the public), he would be right that I would be hypocritical to complain about my tax dollars not being spent on things I approve of, and he would be correct to warn me of the terrible implications of letting non-politically-correct people have the same rights of conscientious tax objection that I claimed for myself.

If I believed, as he does, that individualism and assertions of conscience are the tools of an evil neoliberal agenda, then I might heed his warning about the anti-collectivist assumptions behind conscientious objection.

As I don’t share these points of view with Rodríguez and the left/progressive audience he’s writing for, most of his arguments are lost on me.

What remains is some critique of tax resistance as being largely ineffective and based on exaggerated assumptions about its influence on those in authority (which I suppose I can grant on some level), being more likely to result in reduced government spending on “the good stuff” than “the bad stuff” (which distinction impresses me less than he might think in any case), and being elitist to boot.

The elitism charge is because income tax resistance is an option mostly available to people who have enough income to owe income tax and who are in the relatively privileged position of not having income tax automatically deducted from their paychecks.

Rodríguez bristles at the idea that those who owe more taxes can resist more taxes, which makes tax resistance a sort of “regressive” activism, I guess, that the rich can buy more of than the poor.

This strikes me as ludicrous.

Of course, from the point of view of the resisters, a rich person isn’t getting away with more resistance by having more to resist so much as he is more badly complicit in the government’s misdeeds if he doesn’t resist and redirect, and so he has a stronger obligation to do so than most.

Quite the opposite from what Rodríguez infers.

And the idea that tax resistance is bad because it isn’t a universally-available option is just as silly.

It’s like telling people they shouldn’t burn their draft cards because women and the elderly would be unable to fully participate in such a protest.

(Notably, the protests Rodríguez himself champions — withdrawing your savings from banks and selling off your real estate — seem if anything even more susceptible to his “elitism” critique.)

Most challenging to me was Rodríguez’s attitude towards conscientious objection in general.

He sees conscientious objection as a narcissistic substitute for effective political action:

In this, Rodríguez is a sort of utilitarian anti-Thoreau.

Thoreau was the great champion of conscientious objection — it’s not my duty, he said, to end injustice, but I must not myself behave unjustly:

But although I’m about as Thoreauvian as they come, I admit that Rodríguez’s position also has its attraction.

I do sometimes feel the narcissistic pleasure of polishing up my conscience in the privacy of my own soul and then taking it down from the shelf from time to time to admire it some more, and at the same time I recognize that my opinion of my own conscience is of no value to anybody but myself, and nothing good can come of such a pastime but only reckless pride and stupid self-satisfaction.

It is good to have clean hands, but there are better things to do with them than to admire them.

But it’s not as though Rodríguez, with his more utilitarian approach, were thereby immune from self-satisfaction.

It’s not as though he can think, “I am willing to debase myself, to take on horrible moral burdens, if this is what it takes to make a better world.”

I’m sure he sleeps well with his approach too, and has just as many opportunities to pat himself on the back.

Truth is, I’m much more suspicious of the kind of self-congratulation I might engage in if I thought I was doing whatever-it-takes in pursuit of noble utilitarian ends, than I am about the dangers of an ascetic and aloof self-regarding virtue in the Thoreauvian mold.