From the New Zealand Observer and Free Lance:

Police Hysterics.

A Mountain out of a Molehill

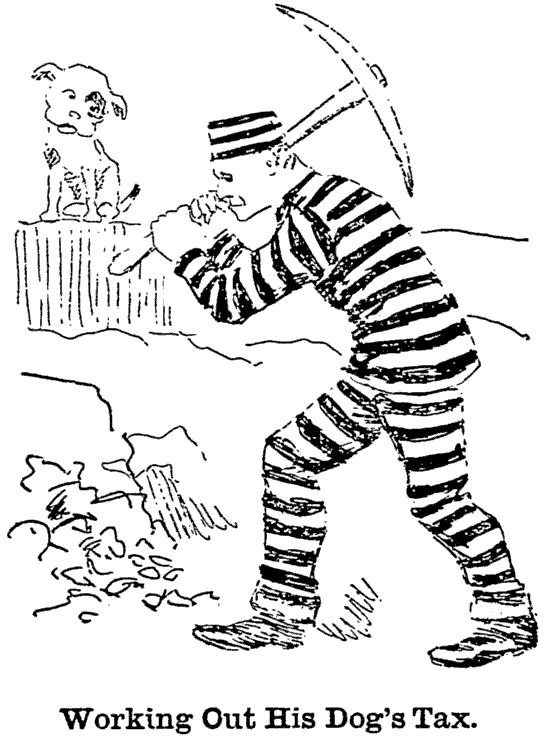

If that Maori difficulty up North does not lead to the effusion of blood and develop into a first-class sensation it won’t be from any lack of determination on the part of the authorities to put the fat in the fire. A few Maoris up in the neighbourhood of Hokianga refuse to pay the dog-tax, and a bounceable fellow named Hone Toia makes use of some vague threats, and forthwith there is a devil of a pother in the country. One would almost imagine there never had been a native difficulty in the colony before, and that there are enough Maoris up North to drive the settlers into the sea.

No overt act has been committed, and yet we have Inspector Hickson, up at Hokianga with a detachment of police and Permanent Force men at his heels, pouring sensational telegrams into the Government at Wellington, and stirring them up into such a condition of excitement and alarm that the Hinemoa has been despatched in eager haste from Cook Strait with a hundred or so of Permanent Artillery and Torpedo Corps men equipped with a field battery of Nordenfeldt and Maxim guns. And, in order that no possible precaution may be neglected, Dr Erson has been summoned from Onehunga to look after the wounded in posse — that is to say, they expect to have some wounded for him to attend to.

Still not a blow nas been struck, and the only foe there is to face is a couple of score of discontented natives who feel a bit pouri because summonses are out against them for that obnoxious dog-tax. All that was wanted was a level-headed, tactful man of resource to cope with this trouble at its inception, and all this fuss and worry and farfarronade would never have been heard of. Inspector Hickson is not built that way. He started out with the idea in his head that he had to suppress a rebellion, and he lost no time in making a tremendous hullaballoo over the job he had in hand.

How strikingly in contrast was the action of Inspector Pardy at that hot-bed of native disaffection — Parihaka — when Te Whiti had but to give the signal and there were hundreds of Maori braves ready to take the field. Yet when several bounceable natives made trouble there some years ago, Inspector Pardy went boldly out with a couple of policemen, arrested the ringleaders, and quelled the trouble in a single act.

All that was needed at Hokianga was an Inspector Pardy to act in a similar way. But what do we find? While Mr Clendon, Stipendiary Magistrate, who has spent a lifetime among the Northern Natives, is wiring to Wellington that he has visited the settlement of these few dissatisfied Maoris at Waima, and is of opinion there is no immediate cause for alarm, we have Inspector Hickson, in a great state of fluster, telegraphing to Ministers in Wellington about those “rebellious natives,” and describing them in absurdly inflated language which smacks of the sixpenny shocker, as “fanatics who fear not death.”

What does Inspector Hickson know about them? He does not appear to have seen any one of them yet, or to have got within coo-ee of them, although he is at the head of a pretty strong and well armed force — strong enough, in fact, to overawe all the Maoris between Hokianga and the Bay of Islands. He is calmly waiting for the Government war steamer, with our standing army on board and those Maxim and Nordenfeldt guns.

We earnestly hope that there will be someone with a cool head up there to stay the outbreak of hostilities. Are we seriously going to start mowing down with Maxims and Nordonfeldts a mere handful of defenceless Maoris? One shot fired in anger may provoke a dreadful slaughter. And supposing Inspector Hickson, with the fever of war galloping through his veins, opens fire on these alleged fanatics and their women and little children, do the people who are concerned in this business reflect that they will have to answer for it to an indignant country whose martial ardour is not usurping its judgment?

There is still the hope that the Maoris themselves — fanatics though Inspector Hickson calls them — may set us the example of prudence and self-restraint that seem to be so sadly lacking on our side. Such an hysterical ebullition of excitement and warlike display it would be difficult to match outside a nigger minstrel show. So far as it has gone, it reflects no credit upon the authorities, and we trust to the good sense of the Maori malcontents that it may go no further. If it does, then the colony will assuredly demand to know the reason why.