Here are a few more data points regarding the “Rebecca Riots.” A letter from Colonel George Rice Trevor includes this detail:

I have just heard that on there was a meeting held in the village of Pontyberem, attended by 2 or 300 persons, most of whom, it is said, were armed and disguised, and that there were several hundred more who appeared to be lookers on. These men, it is said, made the inn-keeper swear not to entertain Lewis, the Toll Collector, and also made some special constables promise not to serve, and took away their staves.

A later letter from the same author shows how difficult it was for the government to get local juries to act against the rioters, and the extent to which the government was going to try to find cooperative witnesses:

About , a party of men disguised in white dresses, went to Hendy Gate, about half a mile from Pontarddulais. They carried out the furniture from the toll-house, and told the old woman, whose name was Sarah Williams, to go away and not return. She went to the house of John Thomas, a labourer, and called him to assist in extinguishing the fire at the toll-house, which had been ignited by the Rebeccaites. The old woman then re-entered the toll-house. The report of a gun or pistol was soon afterwards heard. The old woman ran back to John Thomas’s house, fell down at the threshold, and expired within two minutes. She had received several cautions to collect no more tolls. On an inquest was held before William Bonville, Coroner. Two surgeons, Ben Thomas, Llanelli, and John Kirkhouse Cooke, Llanelli, gave evidence that on the body were marks of shot, some penetrating the nipple of left breast, on in the armpit of the same side, and several shot marks on both arms. Two shots were found in the left lung. In spite of all this evidence the jury found “that the deceased died from effution of blood into the chest occasioned, suffocation, but from what cause is to this jury unknown.”

[T]he Secretary of State will authorise the offer by you of Her Majesty’s most gracious pardon to any person concerned in the murder of the woman at Ponthendy gate, who shall give information and evidence so as to convict the offenders, excepting such persons as actually fired the shot which deprived her of life. And also that he will recommend of the payment of a further reward of £200 in addition to that sum offered by Mr. Chambers for the detection of the persons who set her property on fire, excepting always anyone who actually set fire to the premises and stacks, and so that no principal offender shall receive any part of the award in question. He will advise in this case the grant of Her Majesty’s most gracious pardon to an accomplice under the same restriction, namely, that it is not to be extended to any one who actually set fire to any of the property consumed.

A page devoted to Trevor, the government’s main man on the ground in Carmarthen includes these details:

George Rice Trevor rushed back from his London residence to take over the responsibility of law and order in Carmarthenshire from his elderly father, a task he undertook with evident relish. And when Rebecca burned down corn stacks on his own Dinefwr estate in Llandeilo he quickly discovered he had a personal interest in the drama that was rapidly developing in his own backyard. And there was more to come, as his biographer in the Dictionary of National Biography (DNB) reveals:

Trevor assured a meeting of magistrates at Newcastle Emlyn in that he would order troops to fire on the rioters if necessary. The response of the protesters was predictably fearsome: in , they audaciously dug a grave within sight of Dinefwr Castle, the family seat, and announced that Trevor would occupy it by . Trevor, however, surrounded by soldiers, survived unscathed.

A note in the book The Statutes of Wales gives more evidence as to the antiquity of the peculiar form of the insurrection:

Although the Rebecca riots are chiefly remembered in connection with Wales, it is extremely interesting to note that nearly one hundred years earlier similar disturbances took place in England, where turnpikes had been first established. In , a great number of people in Somersetshire and Gloucestershire, some disguised in women’s clothes, headed by leaders on horseback with blackened faces, had attacked the turnpike gates in those counties. They were called “Jack a Lents.” The course of these disturbances was much like that of the later Rebecca riots of the nineteenth century in Wales.

Following is a report on a paper that George Thomas read before the Cardiff Naturalists Society on “The Riots of Rebecca and Her Daughters”:

In the early part of his paper Mr. Thomas pointed out that the phrase “Rebecca and her Daughters,” by which the turnpike rioters of South Wales were known, had probably a Biblical origin, being assumed in irreverent allusion to the blessing pronounced on Rebekah, Isaac’s wife, — “Be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them.” (Genesis ⅹⅹⅳ. 60.) The name “Becca” was not confined to one individual, but was given to the leader for the occasion. Similar disturbances had occurred in Gloucestershire and Herefordshire as far back as , accounts of which appear in the public prints of the time.

The “Becca” riots in South Wales took place in . They originated in the circumstances of the turnpike roads being held under separate trusts, the trustees of which found it necessary, in order to protect the interest of the tally-holders, to place their gates near the confines of their districts, so as to prevent persons from other districts travelling over their roads free of charge. It thus happened that, while persons living and travelling within any given district were usually charged with only one toll for the use of a considerable length of road, those living on the borders and having occasion to travel out of the district had frequently to pay at two gates within a comparatively short distance. This was not unnaturally felt to be a grievance, and Becca’s action was at first directed to its removal, though not by legitimate means. “She” was at first disguised in woman’s clothes, and when attacking a gate called on her “children” to pull it down. Persons more ill-disposed than the original malcontents were soon mixed up in the disturbances, which speedily assumed a serious aspect, and culminated in threatening letters, theft, arson, and murder. Several country gentlemen in the County of Carmarthen appealed through the Press to the better feelings of the people. Amongst others were Mr. Johnes, of Dolau Cothi, who issued an address to the inhabitants of Conwil Gaio: Col. Trevor (afterwards Lord Dynevor), who issued a proclamation as Deputy Lord-Lieutenant; Mr. Fitzwilliams and Mr. William Chambers, junior. The bard “Tegid” (once Hebrew Professor at Oxford) made a fervent appeal to the people of Nevern parish; and “Brutus,” the talented editor of the Haul, firmly supported the unpopular side of law and order. The chief incidents in connection with Becca’s proceedings began in the neighbourhood of St. Clears and Whitland on . Trefechan Gate was destroyed, Pentre and “Maeswholan” soon followed. , Mynydd-y-Garreg Gate destroyed; , Tavernspite and Lampeter Gates destroyed; , Bwlch-y-Clawdd Tollhouse demolished; , Bwlchtrap Gate destroyed; Trefechan Toll-house demolished; , Pont Twelly and Troed-y-Rhiw Gribyn Toll-gates destroyed; , Water Street Gate, Carmarthen, destroyed. After Water Street Gate was destroyed, some persons from Talog passed through before it was replaced, and refused to pay toll. For this they were fined by the Magistrates at Carmarthen Petty Sessions, and constables were sent from Carmarthen to levy the fines. The constables were, however, forced to return without executing the distress warrants. About 30 pensioners were then sworn in to assist in executing the warrants, and having seized the goods of one Harries, of Talog, they were on their way to Carmarthen, surrounded by about 400 of the Beccas (about one hundred of whom carried guns) and obliged to fire their pistols in the air and to give them up. They were then forced to march to Trawsmawr, the residence of Captain D. Davies, who had signed the warrants, and to return emptyhanded to Carmarthen. The walls round Trawsmawr were demolished, and it was reported that the pensioners were compelled to assist in their destruction. Further damage was done to the walls and plantations at Trawsmawr by the rioters on the night of . , Penllwynau Gate and House destroyed. On , riots took place at Talog, and on meetings were held in the evening at Trelech, Talog, Blaen-y-Coed, and Conwil, at which it was resolved that ’Becca and her children should visit Carmarthen on the ensuing Monday. Rich and poor were required to be present at the Plough and Harrow Public-house, Bwlch Newydd, at eleven o’clock, on pain of having their houses and barns burnt. On the , Melindre Siencyn Toll house was demolished, and Bwlch-y-Clawdd Toll-house shared the same fate. On , ’Becca was discomfitted at Carmarthen Workhouse by the 4th Dragoons (Queen’s Own) under Major Parlby. On this occasion, the late John Lloyd Davies, of Blaen-dyffryn, with his friend, John Lloyd, of Allt-yr-Odyn, met a large body of men on their march to Carmarthen, with the view of “showing their strength,” and tried to dissuade them from their unwise purpose, promising to exert himself to get their grievances inquired into. His patriotic counsel was given in vain. The procession reached from the gaol through Spilman Street, Church Street, St. Peter Street, to the King Street end of Conduit Lane, and numbered from 2,000 to 2,500 persons. A man disguised with long hair rode in front on rather a low horse. It is believed that at first there was no intention to commit excesses, and that the country people were led to the workhouse by some town roughs. Others maintain that the attack on the workhouse was deliberately resolved on at the meetings held the previous Wednesday at Talog and other places. Be that as it may, to the workhouse they went. The dragoons were expected earlier than they arrived, having, it is said, been misdirected by a countryman whom they met between Pont-ar-Ddulais and Carmarthen. They came just in time to save the workhouse, and possibly the neighbouring brewery, the contents of which might have given further impulse to the fury of the rioters. They were met by Mr. T.C. Morris, Mayor, who rode on with their officer. Sweeping through Red Street and Barn Row, they charged, at gallop, up the hill, their armour glistening in the sun. Just at this instant, the work of destruction had begun, the beds being thrown out through the windows. It was amusing to witness the consternation the arrival of the soldiers occasioned. The country people fled in every direction, like ants when an ant-hill is disturbed, fleeing they knew not whither, none seeming to look back. A goodly number were taken within the workhouse walls, many of them being merely curious spectators of what was going on. , Penygarn Toll-house destroyed. , Llandilo-rhwnws Toll-house destroyed. , riot at Talog. , Pont-ar-Lechau Toll-house destroyed; , Porth-y-Rhyd Toll-house demolished; , the house of D. Harries, Pant-y-Fen, invaded; murderous attack on Mr. Edwards, Gelli Gwernen, near Llanon. , Glangwili Tollhouse demolished. Riot at Pont-y-Berem , £500 offered for discovery of the ringleader. , Llanddarog Toll-house attacked. , Sarah Williams, aged 75, toll-collector of Hendy Gate, Llanedy, was shot at the gate-house; hitherto the riots had been free from bloodshed. The first life taken was that of the old woman; she had ignored repeated summonses served upon her by Rebeccaites to quit the place, and in the small hours of a Sabbath morn woke to find her thatched cottage in flames. Rushing out, she raised piercing cries, and hurrying to the house of a neighbour piteously appealed for assistance — er mwyn Duw — to put out the fire. He, grasping the situation, and fearful of the consequences, refused to move. She returned, and was making frenzied efforts to save her “household goods” from the flames, when the report of a rifle was heard, and staggering forward, the woman fell dead, the bullet having pierced her breast. Some consolation for this cowardly deed may be obtained from the fact supplied by a subsequent confession that it was the thoughtless act of a youth, and that there had been no intention whatever to injure the poor, offenceless creature. This tragic incident filled the party with consternation, and they quickly returned from whence they came. Actions such as these caused a revulsion in public feeling, and as disintegrating influences were actively at work within the ranks of the rioters, the task of the authorities, especially as their arrangements gained completeness, became easier. After this about a dozen toll-houses and gales were destroyed, and the house of Mr. Rees, Llandebie, demolished.

Much was expected by the reverse suffered by the rioters at Carmarthen, but subsequent events showed that those had been oversanguine who, in the first flush of victory, had been tempted to believe the campaign over. Far from being the end, it was merely the beginning. Carmarthen was the scene of the first open defiance of the law.

In the police and the ’Beccas came into collision at Pontardulais. Acting upon the statement of an “informer,” Captain Napier, the superintendent, and eight armed police, lay in ambush near a threatened gate. “Mid-night gave the signal sound of strife.” A body of mounted men galloped down the road, dismounted and wrecked a smithy, and then the adjacent gate. They had well nigh completed their self-imposed task when the police “broke cover.” Volleys were exchanged with disastrous results, for the rioters, in the lurid glare of the torches they carried, afforded excellent targets for practice for the police. A battle ensued, and the rioters, demoralised by the surprise, fled, leaving six prisoners in the hands of the law. Once clear of the melee, they rallied and attempted a rescue, but the police, having meanwhile being reinforced by some soldiers, easily beat off their assailants. One of the prisoners, who had been severely wounded, was a young farmer of Llannon, John Hughes by name, subsequently transported for twenty years. He was a few years back a wealthy landowner in Tasmania. The increased vigilance of the authorities; the reaction in public sentiment; and the growing heinousness of the acts committed in the name of Rebecca were factors in promoting the rapid decline of the movement. On , the Royal Commissioners formally entered upon their duties; I knew two of them personally, — the Hon. Robert Henry Give, Lord Windsor’s grandfather, and Major Bowen, father of the late Mr. Bowen, Q.C. They made full and diligent enquiry into the state of the laws administered in South Wales regulating the maintenance of turnpike roads, highways, and bridges; and also into the circumstances which led to acts of violence in certain districts. The suppression of the riots was followed by this inquiry into their cause, and the result was the passing of the South Wales Turnpike Act, which remedied the evils that led to them. The disturbances may be said to have terminated with the capture of “Shoni ’Scybor Fawr,” whose violence and daring made him the terror not less of the police than the country folk with whom he professed to be in sympathy. A noted pugilist of magnificent physique, Shoni had used his giant’s strength like a giant. I knew Shoni, and recollect him fighting at a Llandaff fair, and I can recall when he engaged to fight Harry Jones, of Cardiff, on the Great Heath. In this they were disturbed by county magistrates acting in the Hundred of Kibbor, when two justices, the late T.W. Booker Blakemore, of Velindre, and the late Rev. R. Prichard, came on the scene. Shoni and Harry, with hundreds of their backers, fled, and having crossed the river Rhymney by a wooden bridge near Coedygoras, they fought on the other side of the river in the county of Monmouth, and out of the jurisdiction of the Glamorgan Justices. Shoni was a native of Yscubor Fawr, Penderyn, near Merthyr Tydfil, and a brassfitter by trade. He was taken by a band of constables of A Division of the London Police, at the Five Roads Tavern, Pontyberem, who pounced upon him unawares, and before he could grasp his gun had his wrists in the embrace of the “darbies.” It was with a sense of relief the people received the intelligence of his capture. About twenty of those captured at Carmarthen on the fateful day of the demonstration, were tried before Baron Gurney and Mr. Justice Cresswell, were found guilty, and ten of them sentenced to be transported. Amongst the prisoners found guilty before Judge Cresswell, were two of more notoriety than the rest: “Shoni ’Scybor Fawr,” and “Dai y Cantwr.” Shoni, an ignorant ruffianly fellow, convicted of the more heinous offences committed during the period, was sent to transportation for life. “Dai,” whose sentence was for twenty years, was a man of a different stamp, and deserved the pity generally extended to him. He was a native of Treguff, in the parish of Llancarfan. While imprisoned, awaiting his removal, “Dai y Cantwr,” who was a poet of considerable merit, composed a lament, which, if your good patience will allow, I will read to you.

Lament of DAVID DAVIES (Dai’r Cantwr) when in Carmarthen Gaol for the Becca Riot.

(Translation by Evan Watkin, Jun., Pentyrch, from the Welsh).

Alas! what a sight to the world I shall be,

I have lost all the fame I could win were I free,

Unworthy is the brand and heavy the blow,

And sad is the way I was brought to my woe.

While yet but a youth I’ve misfortune and pain,

My freedom I lose and my bondage I gain;

Commencing life’s journey, an exile am I,

Sent forth from my country, it may be to die.

My father I’m leaving — his kindness and care,

In a land among; negroes my home they’ll prepare.

O’er seas I’ll be carried far from this loved shore,

How sad the misfortune — I’ll see no more.

I am going as an exile, I am going in my tears,

I am borne into bondage for twenty long years,

Ah! long will it be ere I’ll see you again,

For sore are the means and the sorrow’ll remain.The song that I sing is a farewell song

To the dear native land I have loved so long,

For the good I have got, in the days that are past,

On the banks of her rivers so famed and so fast.

Farewell unto Cambria — to leave thee I am bound,

Farewell every meadow and bush-covered mound;

If in the whole world there’s a garden to see,

Oh! beautiful Britain ’tis thee, it is thee.

Farewell, sons of Gomer, for soon I shall be

Sent forth to a land that’s a Babel to me;

My journey is long, o’er the ocean’s wild wave,

May God be my guardian — He’s mighty to save.

Farewell, lovely maidens, so fresh and so fair,

The beauty of none with your own will compare;

As nature has power by pain to atone,

This David must leave you to suffer alone.Treguff with its palace will soon be forgot,

For anguish and sorrow is David’s sad lot,

The thought of journey is melting my heart,

As far over the billows I soon must depart.

Saint Athan rich parish must read in my rhyme,

And Cadoxton, too, where I dwelt for a time,

And often and long I’ll remember Bridgend,

May God be with all to protect and defend.

Oh! noble Glamorgan, I bid thee good cheer,

Thy bells will be tolled never more on my ear,

To tell of thy meadows and dales I will dare,

The Garden of Eden was never more fair.

Farewell unto Monmouth so dear to my heart,

And Troed-y-Rhiw’r Clawdd which is strong on my part;

And as for the people who dwell at Tredegar,

To do me a kindness they ever were eager.It may be that someone will ask with delight,

The name of the bard who has striven to write;

And seeing that now he is going away,

I’m certain you’ll grant him permission to say.

In the land of Glamorgan this gladsome youth dwelt,

And now in his fetters his heart would fain melt,

In a Carmarthenshire prison he’s safe in his cell,

By anguish more torn than he ever can tell.

Llancarfan’s the parish that had my life’s morn,

Treguir, in that parish, is where I was bom.

And now, as I am going to quit your bright shore,

I’ll give you my name, for I’ll see you no more;

My name’s David Davies, I bid adieu;

May God give long life and protection to you.In conclusion, I may say I am greatly indebted to Mr. Spurrell’s “Caermarthen and its neighbourhood,” and to Mr. David Davies, for his account of “Rebecca and her daughters” in the Red Dragon, vol. Ⅺ.

The Bro Beca Project is collecting information about the Rebecca Riots. They’ve also hosted toll-house burning reenactments, and a ballad competition to reward poets who memorialize the Rebeccaites.

An article by James Mason from an edition of Littell’s Living Age shows how the sharp edges of the story’s details were starting to wear away as it got preserved for history:

Rebecca and Her Daughters

What were known as the “Rebecca riots” took place in South Wales about fifty years ago, and form a curious and exciting chapter in the history of that portion of the principality.

Far beyond the memory of the oldest inhabitant the people there had been going on in a quiet way, attracting little notice and giving no trouble. All of a sudden, however, they developed into moonlighters, running wild between supper and breakfast time, taking the law into their own hands, and demolishing public property in a wholesale fashion.

There was a good deal that was comic about their proceedings, and the impression made on the rest of Great Britain was much what would be produced in ourselves if some of our decorous friends were, without any preliminary intimation, to take to playing the part of clowns and mountebanks. The rioters at first were almost frolicsome, and if peaceful districts were turned upside down it was done with such good-humor that outsiders felt more inclined to laugh than regard it seriously.

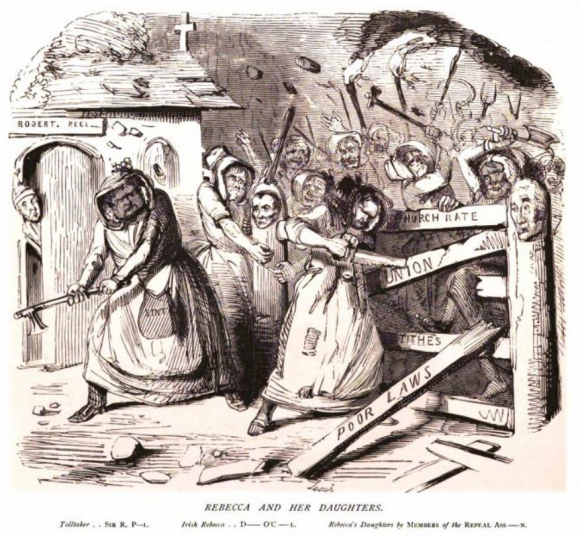

Those who took an active part were invariably headed by a man dressed in woman’s clothes, who went by the name of Miss Rebecca. The costume might have been assumed because it made a good disguise, but ill-natured people were not wanting who held it to be a concession to the popular notion that there is a woman at the bottom of every mischief. Many of those who accompanied Rebecca were disguised in the same fashion, so that they looked like a family party, and came, naturally enough, to be known as “Rebecca and her daughters.”

The first cause of all the disturbance was toll-gates. These were objects of Rebecca’s hatred, and to pull them down and smash them in pieces was the end of her midnight expeditions. She got her name, indeed, through this destructive occupation. They called her Rebecca in allusion to Genesis ⅹⅹⅳ. 60: “And they blessed Rebekah, and said unto her, Thou art our sister, … and let thy seed possess the gate of those which hate them.”

It was no imaginary grievance. The tolls then levied in South Wales constituted an unfair and intolerable burden. Every town and almost every village was approached by a gate, the road trusts of South Wales being eager to lay hands on money, for through bad management they were, without exception, deep in debt.

The people lived in a perfect network of toll-gates and bars, and going even a few miles meant sometimes a heavy expense. Farmers and dealers making their way to fair or market, not unfrequently found by the end of their journey that they had paid away in tolls more than the value of their load. One man trading in the neighborhood of Merthyr Tydvil told that he had four turnpike gates to pass through within six miles.

There were five different trusts leading into the town of Carmarthen, and it was stated by the clerk of one of these, that any person passing through the town in a particular direction would have to pay at three turnpike gates in a distance of three miles. This might not seem objectionable to a man driving to see his sweetheart, but no one can wonder at hard-working people in pursuit of business finding it a hardship. It was all the worse because times were bad and the greater number of those using the roads had little capital to boast of except their own industry.

Who first suggested making war on these gates is unknown. The first act in the campaign occurred in the summer of . Four gates had been erected in a trust called the Whitland Trust, on the borders of Pembroke and Carmarthen, and it was generally held that the erection was illegal. It might have been so, but the trustees had large powers, and in Carmarthenshire at least they would have been within their rights had they established a gate and demanded toll at intervals of a hundred yards each throughout the county. The gates had not been up a week when the country people assembled one fine evening about six o’clock and pulled them down “amidst all sorts of noise and disturbance and great jollity.” The fun of the thing seems to have been considerable, and the rioters made no attempt at concealment. No one interfered with them, and when the gates were demolished they dispersed quietly to their homes.

The trustees resolved to re-erect the gates, but a number of noblemen and gentlemen of the county who sympathized with the people qualified as trustees, and by their votes overturned this decision. Peace was now secured for a time, but the enemies of toll-gates felt they had scored a victory, and laid their heads together to plan destruction on a grand scale.

The plot took some time in hatching, and nothing happened till the early part of . Rebecca then began operations with a large following, well mounted and sometimes armed.

The demolition of gates began in Carmarthenshire, and the infection quickly spread, extending first to the neighboring counties of Pembroke and Cardigan, and then to Radnorshire and Glamorganshire. The only one of the south Welsh counties that escaped the influence of Rebecca was Brecknock.

Gate after gate disappeared before the axe and hatchet. In what was known as the Three Commons Trust in Carmarthenshire there were twenty-one gates and bars, and all were made an end of but two. In many other trusts the damage done was on the same scale; some had not even a single gate left standing. When the outbreak began there were in the county of Carmarthen alone between a hundred and a hundred and fifty gates. Of these between seventy and eighty were soon swept away.

The method adopted was a rough-and-ready one, and as cheerful as Rebecca and her lively family could make it. The toll-collector and his family, all snug in bed, are wakened about midnight by a clattering of horses’ hoofs outside. Then half-a-dozen horns blow a blast, and a thundering knock comes to the door.

The collector, knowing too well that it announces the end of his occupation, looks out, and by the light of the moon sees a considerable troop of horsemen. There are a few men on foot, but the greater number are mounted. One dressed as a woman seems to be taking the lead — that is Rebecca. About her is a bodyguard, with shirts over their clothes and faces blackened, and wearing bonnets or the tall hats of their Welsh wives.

The door being opened, they assure the inmates that they mean no personal harm, Rebecca making war not against people, but against toll-bars. “Get out your furniture,” says that mysterious commander, “and then be off with you!”

They set to work to remove the furniture, Rebecca’s troop meanwhile devoting attention to the gates. The strong oak posts are sawn off close to the ground, and then with hatchets and handbills the gates themselves are broken in fragments.

Tables, chairs, beds, and bedding are soon piled up by the wayside, after which the word of command is given, and willing hands begin the destruction of the house, and never leave off till nothing remains but a dusty heap of bricks, laths, and plaster.

Their work ended, they make the gatekeeper kneel down and swear never again to earn a living by collecting tolls on the queen’s highway. They mount their horses, there is a triumphal performance on the horns and off they gallop, leaving the débris of the toll-gates and toll-house littering the road, and the collector, with his wife and children, watching over their “bits o’ sticks” and wondering whether the whole affair is not a dream.

Who the destroyers of gates were and whence they came no one knew, and whither they went when their work was done no one knew either. They left no trace any more than if they had been spirits of the air and their leader the queen of ghosts and shadows. The country day by day, after their midnight pranks, was as quiet as one could wish it to be. It was evident that they were well organized and disciplined, and fully aware of the importance of keeping their own counsel.

Many guesses were hazarded on the subject of Rebecca. Some said she was a “disappointed provincial barrister” — an improbable solution of the mystery. Others would have it that she was a political agitator, bent on making the abolition of tolls the seventh point in the Chartist programme, and “dark hints were dropped and mysterious stories told of strangers seen here and there, and men in gigs, of suspicious appearance and without ostensible business, who were, beyond all doubt, connected with the movement.”

“But,” says a contemporary writer, “the supposed sole chief and director of the campaign must have been gifted with ubiquity, for Rebecca was in three or four counties at the same moment,—

Methinks there be two Richmonds in the field!

With one hand she smote an obnoxious toll-gate in Radnorshire, and with the other she cleared a free passage for the traveller to the wild coast of Pembroke.”

The probability is that each district had its own Rebecca, who planned the various enterprises, and was recognized as chief by the rest of the band. Whether the districts worked independently, or had a common centre of action, is uncertain.

The forces of Rebecca for a while had pretty much their own way; indeed, the contest with the authorities was a very unequal one. Of all the counties affected, only Glamorganshire at that time possessed any paid constabulary, or any force that could be of service.

When a gate had been pulled down it was labor thrown away to re-erect it, for Rebecca was sure to pay another visit and level it to the ground again. One gate was destroyed five times in succession.

Finding that restoring gates, rebuilding houses, and offering large rewards for the apprehension of the rioters failed to produce any satisfactory result, the trustees lost heart. Roads were left free of toll, and people went to and fro without having any longer to put their hands in their pockets every two or three miles.

This was a popular triumph, and brought to a close the first act in the comedy of Rebecca.

The appetite for agitation grew by what it fed on. One subject for discontent suggested another, and so on, till many of the imaginative natives of South Wales began to consider themselves the most ill-used people under the sun.

The cry of down with toll-bars had added to it down with a dozen other grievances. For the discussion of these, meetings were held on hillsides, by mountain streams, and in all sorts of out-of-the-way places. They were attended chiefly by small farmers, an industrious and thrifty class but almost entirely without education, and incapable of estimating at their true value any assertions that might be made to them.

Amongst the subjects of complaint were the operation of the Poor Law Amendment Act, the cost and difficulty of recovering small debts, and the payment of tithes. Then Englishmen in office in South Wales were objected to, so were high rents, so were increased county rates, so were fees paid to magistrates’ clerks in the administration of justice — in short, Rebecca was called upon to deal with everything inconvenient and unpopular.

Their growing confidence and excellent spirits now induced Rebecca and her daughters to vary their midnight exploits by showing what they could do by the light of day. A demonstration was planned for the , and the scene of it was to be the ancient town of Carmarthen.

About a large body of rioters was seen approaching Water Street gate from the country beyond. Fear multiplied their numbers, and the news ran like wildfire through Carmarthen that there were thousands of them. A band of music came first, thundering forth the warlike strains of “The Men of Harlech.” Next came Rebecca’s regiment of infantry, an irregular host, in which some bore inflammatory placards, and others cudgels, saws, axes, and hatchets, whilst a few carried brooms to let people know how they intended to sweep away every sort of grievance. After these rode Miss Rebecca, and the rear was brought up by about three hundred farmers on horseback.

At Water Street Gate they met with no obstacle; the gate, in fact, had been cleared out of the way by them some time before. They swarmed up the narrow, steep streets, gathering in numbers as they went. All the loafers joined them, so did all the mischievous and all the discontented of the town. Scores of women, too, fell into the ranks.

When they reached the Guildhall the magistrates were there consulting as to what steps should be taken for the public safety. The mob hooted at them and then turned away to execute the main business that had brought them together. That was the destruction of the Union Workhouse.

They found the lodge-gate and porter’s door of the unpopular edifice securely fastened, and there was a high wall running right round the building. A few of the more nimble climbed the wall, got possession of the keys, and let in the rest. As they did so the clangor of the alarm bell, tugged at by the governor of the workhouse, was added to the martial music of their own band. The horsemen rode into the yard, whilst the rioters on foot entered the building and began pulling down doors and partitions and throwing beds out of the windows.

But they were not going to get it all their own way for long. Information of the intended rising had been obtained by the authorities some days before, and in consequence a troop of the 4th Light Dragoons had been ordered to march to Carmarthen from Cardiff.

The morning of the tenth saw them on the road. Just after passing through Neath, thirty-six miles from their destination, an express met them with an entreaty to make haste, for the demonstration had been fixed for that very day. They pushed on, riding the last fifteen miles in an hour and a half. Two horses fell dead from fatigue just as they entered Carmarthen.

The rioters were warming to their work when the dragoons arrived. With the dragoons came a magistrate, who pulled out the Riot Act, and charged all present “immediately to disperse themselves and peaceably to depart to their habitations or to their lawful business.”

Rebecca’s children made answer by a rush on the soldiers. But they got the worst of it. The dragoons charged, using the flat of their swords, and the rioters soon took to their heels, many who were in the courtyard finding it wise to escape over the wall. About a hundred were taken prisoners, and amongst the spoils were several horses abandoned by their riders. Some of the prisoners were afterwards tried and convicted.

Ill-disposed and designing people now got the upper hand in the councils of Rebecca, and the movement, as every lawless movement is sure to do, went from bad to worse. Under pretense of exposing public wrongs, those who had any private grievances contrived to gratify their spite. Every man who had fallen out with his neighbor and wished to do him an ill turn had now an opportunity.

Letters signed “Rebecca,” or “Becca,” or “Rebecca and her Daughters,” began flying about, conveying hints of vengeance to those who refused to comply with the demands of the writers. They were directed to tithe-owners, turnpike commissioners, toll collectors, magistrates, landlords, and all who for any reason had incurred popular displeasure.

The vice-lieutenant of Carmarthenshire, for example, was informed that a grave had been dug for him in the park of his father, Lord Dynevor, and that he would be laid in it before a day named. To the vicar of two small rural parishes on the coast of Cardiganshire, Rebecca sent word that if he did not make restitution of a sum he had unjustly received he would soon find the balance on the wrong side.

“Unless you give back the money,” she wrote, “I, with five hundred or six hundred of my daughters, will come and visit you and destroy your property five times to the value of it, and make you a scorn and reproach throughout the whole neighborhood.”

This clergyman states that his existence was rendered miserable by the letters he received, and that it had nearly killed his wife. “We never,” he says, “go to bed without having a wardrobe moved to the window as a protection against firearms.”

Besides firing shots in at windows, the discontented followers of Rebecca embarked in incendiarism and set many a haystack in a blaze. One farmer in Carmarthenshire had five fires in one week, in addition to having a horse shot and agricultural machinery broken and thrown into a pit.

They took to dictating to landlords the terms on which they were to let ground to tenants, and to tenants the terms on which they were to rent ground from landlords. The leaders, too, began to levy blackmail on farmers who took part in the riots. A note would come: “You must send such and such a contribution to Rebecca on such a night,” and the farmer who declined knew what to expect.

The humor of Rebecca was at an end. From being a humorist she had become a tyrant. Even the destruction of toll-gates lost its grotesque side and grew to be little else than a matter of ruffianism. Previously, the gate-keepers had been very leniently dealt with, no attempt, except in rare instances, being made either to injure them or to destroy or plunder their property. Now, however, they had a bad time of it, for when a gate was demolished a beating for the man who had kept it came to be the customary termination of the proceedings.

An encounter marked by some ugly features took place at a gate on the borders of Glamorganshire and Carmarthenshire. Something was suspected, and eight policemen had been told off to hide in a neighboring field.

About midnight the forces of Rebecca, including a hundred horsemen, made an attack on the gate. It was soon in pieces, but before the work of destruction was finished the eight constables jumped over the hedge and rushed forward, hoping to secure the ringleaders.

The rioters at once discharged a volley. The police in turn drew their pistols and fired, wounding several and killing the horse of the captain of the gang.

A tough fight followed, ending in Rebecca’s men running off. Six prisoners were left in the clutches of the police, two of them severely wounded. One of these prisoners was a young farmer, who on being tried was sentenced to transportation for life.

A still more unfortunate incident happened at a gate between Llanelly, in Carmarthenshire, and Pontardulais. It was kept by an old woman — she was over seventy years of age. Numerous letters had been received by her to the effect that if she did not leave the gate her house would be burned over her head; but she took no notice of them, and stuck to her post.

About three o’clock one Sunday morning she awoke to find that the threat was being put in execution — the thatch of her dwelling was in a blaze. She jumped out of bed and ran to a cottage close by, calling on the inmates for help to put out the fire. They, however, would do nothing — for fear, they said, of Rebecca’s vengeance.

The old woman hastened home to save what little she could of her humble furniture, but had hardly reached the door when a shot struck her, fired apparently by one of the band who had set a light to the thatch. She died within a few minutes.

It was asserted afterwards — but the evidence is not conclusive — that the fatal shot was “the random act of a lad who accompanied the party, and was fired without any previous or deliberate intention to take her life.” What is certain is, that this was the first life sacrificed in Rebecca’s raids.

Quiet people began to feel uncomfortable, for there was no saying what might happen next. Government was appealed to and urged to do something by way of restoring order. As a first step in that direction troops were sent down to South Wales, and the command of the disturbed districts was entrusted to an officer of experience.

Soldiers were now quartered in the neighborhood of every remaining tollgate; they gave protection to those who bad excited popular ill-will, and kept an eye on all suspected persons. Select companies of London police also appeared on the scene, and were dotted about in villages and hamlets.

This brought to a close some of the more objectionable doings of Rebecca, but did not end her crusade against tollbars. She and her daughters knew the country a great deal better than those who bad been sent to circumvent them, and under cover of night could swoop down on a gate and demolish both it and the collector’s dwelling, without a single soldier or policeman in the vicinity being aware of their goings on.

The military and police were not even wise after the event, for the sympathies of the country people, not to speak of their interests, being with Rebecca, one and all when questioned assumed an impenetrable air of ignorance and reserve. The incomers too were sadly hampered in their inquiries by not knowing a word of Welsh. Occasionally, Rebecca, by way of a joke, would circulate false reports, and troopers would be sent in hot haste over hill and dale to protect gates that were in no danger, finding on their return that the real point of attack had been at the other end of the district.

The restoration of order was greatly helped by the appointment of a government commission of inquiry, whose business it was to investigate on the spot the various grievances of the natives of South Wales.

This commission began its sittings in Carmarthen on the , and in the beginning of issued a report, which, by its temperate statement of the hardship of the toll-gate, secured the passing of an act known as the South Wales Turnpike Act, its chief provision being that no gate should be erected within seven miles of another unless they freed each other. This satisfied most people. Rebecca and her daughters retired into private life, and the lively chapter they had contributed to the history of the principality came to a close.