From the Pittsburgh Press, a news report filed :

Government of England is Alarmed

Many “Dissenters” Getting Into Jail for Refusing to Contribute to Support of Church of England

Boycott of Offensive Tax is Widespread

By Charles P. Stewart.

London Correspondent United Press.

London, . — So many “dissenters” are getting into jail for refusing to contribute to the support of the Church of England schools that the British government is becoming alarmed.

The dispute between the followers of the state church and of the various dissenting denominations — Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists and others — dates back to , when the “compulsory church rate” was made part of the Educational Act. It dragged along until quite recently, however, without attracting much attention. This was merely because the dissenters or “free churchmen,” as they are also known, were not acting unitedly and the number who became involved in trouble with the authorities over their defiance of the law was not great enough to give the matter an appearance of grave importance.

But at last, what amounts to a widespread boycott of the offensive tax has developed. Free church ministers and laymen alike are refusing to pay it. Moreover, they are taking the precaution of putting their property out of their own names, so that the collectors will not have anything to levy on. This means that the authorities have no recourse but to send them to prison and they already have forty ministers and about twice as many laymen of various dissenting establishments behind the bars at the present time.

Men high in English governmental affairs recognize that a politico-religious struggle of this sort has infinite possibilities of danger. They are doing their best to effect a compromise, but so stubborn are both sides and so violently does the average Briton excite himself as soon as the “church question” is touched on that the would-be peace-makers have not only not succeeded in improving the situation, but are almost afraid to suggest anything likely to work an improvement.

As already pointed out it does not necessarily follow that a dissenter goes to jail because he refuses to pay his “church rate.” If he has property the authorities can put their hands on, it is seized and sold for the amount due and this ends the matter until time for the next payment. Thousands of families have had their property seized and sold in this manner. It is going on constantly all over England and there is getting to be more and more of it as the dissenters become more stubborn.

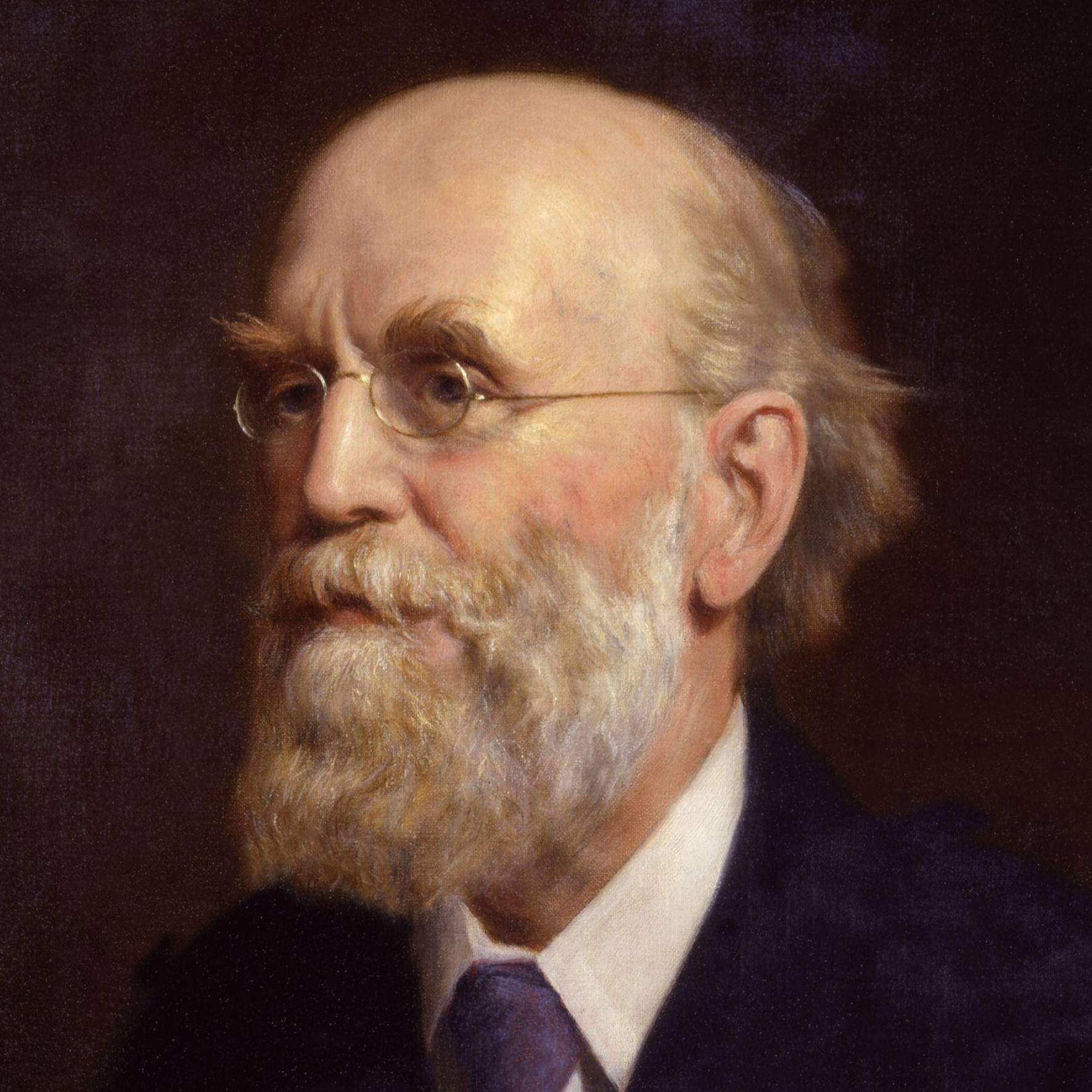

“We free churchmen,” says Dr. Clifford of London, the famous leader of the “passive resistance” party, “will continue to go to prison until all denominations are treated alike by the state or until there are no dissenters out of jail.

“I myself have been trying to get into prison ever since the Education Act was passed, but I have failed. My nearest approach to it is when, four times yearly, the officers come and seize my goods. In my case the church tax comes to six shillings ($1.44) a quarter.

“In the hope of preventing the authorities from getting their money in this way I made over all my household effects to my wife, but the collectors seized them just the same. They take articles of silver, watches and knicknacs which can easily be carried and converted into money. Mrs. Clifford complains that we have not enough silver left to set a table decently.

“I might resist these seizures by setting up the claim that the goods are not mine but my wife’s, but inasmuch as the transfer was not made until after the Education Act was passed and it is obvious that it was made to evade the law, my solicitor advises me that a case of conspiracy might be made out against me for which I could be sentenced to eight years’ penal servitude. I wish to get into prison, indeed, but to do so for eight years is rather serious. I think my services to the free church movement are valuable enough, outside a cell, to make it undesirable for me to sacrifice myself for so long a term.

[“]Will we win this fight for religious liberty? Yes, but not easily. It will take thirty years. The Anglican church is too rich and too closely allied to the House of Lords and the breweries, to be easily disestablished. We free churchmen pay a price for our principles.”

Perhaps the most significant case thus far in connection with the “passive resistance” movement was that of the Rev. S.J. Ford, a well-known Baptist clergyman of Minchinhampton, who was sentenced to two months’ hard labor in “Glousecter Goal” [sic] for refusal to pay his church rate.

Mr. Ford has “done” fourteen days on eight previous occasions without complaining, but two months for 42 cents struck him as a trifle excessive, and he spoke to his chief, Dr. Clifford, about it. The doctor appealed to Home Secretary Churchill who, as a Liberal, sympathizes with the “passive resisters.” He at first gave it as his opinion, however, that he lacked the legal power to interfere with the sentence. Later he changed his mind and ten days ago, after Mr. Ford had served seven days of his time, ordered him set free.

But the reason back of the severity of Mr. Ford’s sentence was even more interesting than the sentence itself. Maj. Ricardo, the presiding magistrate of the court of petty sessions, which pronounced it, was deeply concerned during the last election in the success of the Tory candidate for Parliament, in Gloucester and, with many others, attributed his defeat by a Liberal mainly to the influence of Mr. Ford, who is immensely popular with the workingmen. The clergyman’s appearance before him for refusal to pay the church rate was the first chance he had to square accounts.

“There is,” Dr. Clifford says, “a movement on foot now to have the bench of Gloucester magistrates removed, as political venom was plainly shown. The Lord Chancellor, Lord Loreburn, the head of the English judiciary, can remove any magistrate for cause, so he will be appealed to.”

Mr. Ford came out of prison in an exceedingly cheerful frame of mind. He was quite willing to go there for conscience’s sake, he remarked, but he had no disposition to stay longer than necessary. “Having been in the same jail so many times before,” he added, “I knew the officials there and was received by them, on my entrance, in their usual hospitable manner. They have always treated me with much consideration and humanity. If the same spirit had been shown by the magistrates I would not have received so excessive a sentence. While a prisoner I was employed in sewing the bottoms into mail bags.

“I presume I shall have many similar experiences in future but sooner or later victory will come for the ‘passive resisters’ and for the country’s schools.”

The Ford case is not the only recent one of the kind in which a strong flavor of party politics has been mixed with religion and taxes.

Thomas Watson, of Hull, for instance, a man of 78 years, recently spent two weeks in prison for the same offense charged against Mr. Ford. But the odd part of it was that Watson has been resisting the church tax ever since without getting himself locked up. His property was in his wife’s name, so that collection could not be forced and he might, under the law, have been sentenced any time in .

The whole secret is, however, that he never took the slightest interest in politics until the last election. Then he suddenly took the stump for the local Liberal candidate for Parliament. His interest was due to the fact that the Conservative aspirant for legislative honors was notoriously chosen by the Conservative political boss of Hull, who is a saloon keeper, while Watson is a prohibitionist. He developed unexpected ability as a campaigner and the Conservatives were furious at him. So the very next time the church tax fell due he declined to pay it, old Watson went to jail.

Josiah Godley of Overton is just out of Lancaster prison for a like offense. Like Watson he had neither paid nor been annoyed since . Like Watson he never mixed in politics until the last election. Then he became an active Liberal worker. Time came for the church tax, Godley was asked for it, he refused to pay, he was arrested, he admitted that he could but wouldn’t pay for supporting the schools of a denomination he didn’t believe in and he got 14 days at hard labor.

Enough cases of this kind could be quoted to fill columns. They are causing so much bad blood that there are beginning to be indications of a sentiment among the “passive resisters” of a disinclination to go on making their “resistance” altogether “passive.”

That the oppression, as a matter of politics, should always be of Liberals by Conservatives is in the very nature of things. A follower of the Church of England is not always a Conservative but he generally is if he is a very ardent churchman and Conservatives, practically without exception are Church of Englanders. Liberals, on the other hand, are not always dissenters but dissenters are always Liberals and, speaking broadly, the Liberal party may be set down as a dissenting party. That is, so far as religion and politics are mixed — which in England is a great deal.