I gave my opinion that violent struggle for political change in the United States was unwise and likely to be counterproductive. But I also expressed frustration at the ingrained ineffectiveness of today’s nonviolent protests, and tried to imagine what an effective nonviolent resistance might look like.

I’m not a doctrinaire pacifist the way Gandhi was. I can imagine causes I would kill for as well as those I would die for. And yet it seems to me that we’re more likely to reach the goal worth aiming for — and I’m speaking here practically and not just idealistically — through nonviolent means.

I recommended yesterday that “[p]eople who are committed to (or who prefer) nonviolence and who regret the rise of the ‘black bloc’ and other violent protesters should ask how Gandhi prevented the Indian National Congress from choosing the tactics of those in India who were advocating armed insurrection.”

“The answer,” I suggested, was that Gandhi “was more hard-core than they were, and he demonstrated results.” But I decided to take my own advice and take a closer look, since I’m not a scholar of the Indian independence movement. I picked up some facts of interest, both about the practical appeal of Gandhi’s program to an Indian National Congress with lofty and concrete goals, and about the importance of, yes, tax resistance in that program.

If we step into the Wayback Machine, we’ll see an India that was fighting for its independence against a hypocritically blind and openly imperalist British empire. Jawaharlal Nehru remembered:

I have always wondered at and admired the astonishing knack of the British people for making their moral standards correspond with their material interests and for seeing virtue in everything that advances their imperial designs. [SNC 160]

The violent struggle for independence in India, which Nehru initially supported, predates Gandhi’s nonviolent satyagraha techniques. In fact Gandhi’s first use of these new tactics in India were in response to the British administration’s draconian anti-terrorist laws which had in turn been designed to fend off the violent independence movement (and which sound awfully familiar):

In the Rowlatt Bills were promulgated. Their intent was to control a few wartime manifestations of terrorism and to prevent their recurrence during the postwar period… They incensed Indians and provided a focal point for resistance. The bills made trial without jury permissible for political offenses and extended to the provincial authorities the right to intern suspected terrorists without trial. On the day they were to become law, Gandhi, fresh from a victorious campaign in Champaran… proposed a nationwide hartal. [SNC 163]

The hartal was something akin to a general strike. The “victorious campaign in Champaran” was Gandhi’s first Indian satyagraha campaign, conducted when he was a newcomer on the political scene without a lot of “cred.” He had been acting independently of existing resistance organizations as the founder of his own group called the “Satyagraha Sabha” because, in his words, “all hope of any of the existing institutions adopting a novel weapon like Satyagraha seemed to me to be in vain” [GAA 456]

The Raj responded to Gandhi’s new national campaign and the outrage over the Rowlatt Bills with violent reprisals, which included perpetrating the vicious Amritsar massacre and imprisoning Gandhi for . Gandhi’s first national campaign of non-cooperation went nowhere.

Yet the Indian National Congress decided against a violent revolutionary movement and chose Gandhi as its commander-in-chief for the coming independence struggle. One of Gandhi’s first acts in this capacity was to lead “what amounted to both a training exercise and a preliminary skirmish” [SNC 166] in Bardoli:

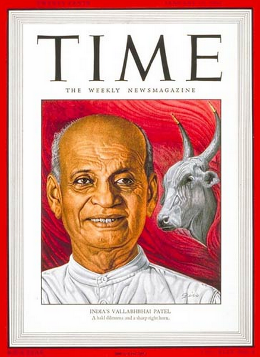

The farmers and peasants of Bardoli were being asked to pay a 22 percent land tax increase after a particularly bad agricultural year. [Vallabhbhai] Patel led them in withholding all taxes until the increase was rescinded. Solidarity was enforced in part through a social boycott of nonresisters. The movement lasted , and ended with the resisters paying the tax into a government escrow account, pending an investigation of the fairness of the tax. The investigation found that the tax was not justified, and it was withdrawn.

The Bardoli experiment demonstrated the power of disciplined collective action. Nonpayment of taxes was an extremely aggressive act and subject to harsh penalties. [SNC 166–7]

Gandhi and the Indian National Congress took heart at this victory. Gandhi wrote about the British: “You have great military resources. Your naval power is matchless. If we wanted to fight with you on your own ground, we should be unable to do so, but… we cease to play the part of the ruled. You may, if you like, cut us to pieces. You may shatter us at the cannon’s mouth. If you act contrary to our will, we shall not help you; and without our help, we know that you cannot move one step forward.” [PNVA 84]

The key, according to Gandhi, was in withdrawal of cooperation. “We recognize… that the most effective way of gaining our freedom is not through violence. We will therefore prepare ourselves by withdrawing, so far as we can, all voluntary association from the British Government, and will prepare for civil disobedience, including nonpayment of taxes. We are convinced that if we can but withdraw our voluntary help and stop payment of taxes without doing violence, even under provocation, the end of inhuman rule is assured.” [PNVA 84]

The goals of the Indian National Congress were lofty. “This was the first campaign in which immediate and unconditional independence for India emerged as the explicit objective and it mobilized more Indians for direct action in the service of that objective than any other single campaign” [SNC 157]. And the rhetoric was correspondingly confrontational. Gandhi wrote: “sedition has become the creed of the Congress… Noncooperation, though a religious and strictly moral movement, deliberately aims at the overthrow of the Government, and is therefore legally seditious in terms of the Indian Penal Code” [PNVA 85].

Gandhi felt that “civil disobedience, once begun this time, cannot be stopped and must not be stopped as long as there is a single resister left free or alive.” This was not a pastime for hobbyists or cowards. Tens of thousands were arrested. Hundreds killed. Protesters had to be willing to be beaten with steel-tipped canes without even raising a hand to ward off the blows.

The first concentrated target of these protests was the Salt Act:

The existence of a government monopoly on salt, resulting from the Salt Act, perfectly exemplified the perceived evils of colonial rule. Paying the tax on salt (and thereby providing much of the revenue to run the colonial regime) was more a mild irritant than a desperate hardship for most. But why pay the bill for their own subjugation? [SNC 172]

Gandhi also tried to extend this campaign to a boycott of foreign liquor and fabric. Wearing homespun clothing (and thereby damaging the economy of occupation while at the same time encouraging self-reliance) became a symbol of resistance.

The Salt March, the Dharasana salt factory confrontation (one of the climactic scenes you may remember from Gandhi the movie), and “also the entire Salt Satyagraha campaign, were, technically, utter failures” when seen from the point-of-view of the lofty goals — that is, complete independence. “Yet now we know that this bloody climax made India’s freedom inevitable, because it showed what the Satyagraha volunteers were made of, and what the oppressive system of government that the British had imposed on India was made of” [ITNOW 113]

Perhaps this is an example of the tendency of losers to use clever fantasy redefinitions to turn their losses into victories, a tendency I complained about on The Picket Line . But it’s true that India did gain its independence, though , and it’s hard to look at the historical record and not conclude that Gandhi’s campaigns made Indian independence inevitable.

And it’s also true that Indians like Jawaharlal Nehru, who was not initially a proponent of nonviolent resistance, came to have respect for the effectiveness of the technique:

We had accepted that method, the Congress had made that method its own, because of a belief in its effectiveness. Gandhiji had placed it before the country not only as the right method but as the most effective one for our purpose… In spite of its negative name it was a dynamic method, the very opposite of a meek submission to a tyrant’s will. It was not a coward’s refuge from action, but a brave man’s defiance of evil and national subjection. [PVNA 87]

Would that we could say the same for the nonviolent resistance movement in the United States today.

- [GAA]

- Gandhi, Mohandas K. An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth Beacon

- [ITNOW]

- Nagler, Michael N. Is There No Other Way?: The Search for a Nonviolent Future Berkeley Hills

- [PNVA]

- Sharp, Gene The Politics of Nonviolent Action: Part One — Power and Struggle Porter Sargent

- [SNC]

- Ackerman, Peter & Kruegler, Christopher Strategic Nonviolent Conflict: The Dynamics of People Power in the Twentieth Century Praeger Publishers