What happened between the time when Peacemakers was leading the war tax resistance charge and , when the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee was founded? There was another group, simply called “National War Tax Resistance,” that took the reins during the Vietnam War.

Here are some more excerpts from Robert Cooney’s and Helen Michalowski’s The Power of the People: Active Nonviolence in the United States about this transition period:

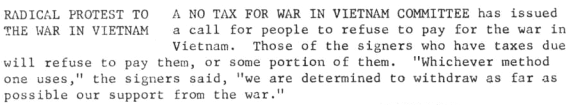

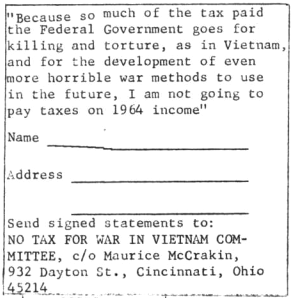

was, as the CNVA Bulletin declared, “The Year of Vietnam.” Picketing and sit-downs across the country marked the announcement of the first US bombing of North Vietnam on . These continued throughout the month and much effort was expended gathering signatures for a new appeal, the Declaration of Conscience, circulated by radical pacifist groups, urging civil disobedience. The Peacemakers group in Cincinnati organized a “No Tax for War in Vietnam Committee” calling for tax resistance. In a separate group — War Tax Resistance, coordinated by Bob Calvert — was established and at the time included some 200 local tax resistance centers across the country.

From the newsletter of the Syracuse Peace Council

Nonpayment of war taxes, practiced by Quakers and others, disappeared as a pacifist testimony soon after the Civil War and Thoreau’s famous stand against the U.S. foray in Mexico. It first reappeared in World War Ⅱ when a few widely scattered individuals refused to pay federal taxes on the grounds that there was no way to prevent a significant part of their money from being used for military purposes. One resister, Ernest Bromley, was prosecuted and imprisoned for his refusal. Many others began to inform the Internal Revenue Service that payment violated their principles.

The enactment during World War Ⅱ of a measure which required employers to withhold taxes from their employees caused particular difficulties for pacifists and led to the formation of Peacemakers in . A Peacemaker committee promoted tax refusal and provided research, literature, action suggestions, and publicity for those in the tax resistance movement. Although many hundreds of people were refusing to pay income taxes during , the government prosecuted and imprisoned only six: James Otsuka of Indiana, Maurice McCrackin of Ohio, Eroseanna Robinson of Illinois, Walter Gormly of Iowa, Arthur Evans of Colorado, and Neil Haworth of Connecticut. These imprisonments and the seizure of a few cars and houses by the IRS, served to highlight the tax refusal testimony and establish it as a major nonviolent principle and tactic.

Tax resistance, like other forms of opposition to the military, increased dramatically during the Vietnam War. In the federal government levied an additional tax on every private telephone, and in a rare moment of candor, admitted that the money would help subsidize the war in Indochina. Peacemakers, the War Resisters League, and other nonviolent groups urged refusal of this tax and in the following years countless thousands heeded their call. Under the leadership of Bob and Angie Calvert, War Tax Resistance was formed in as a separate organization to investigate all aspects and ramifications of conscientious tax refusal. During the war there were over 200 local war tax resistance centers, as well as a number of “alternative life funds” which rechanneled refused tax money back into the local community for constructive purposes. Many of these continued after the end of the war.

The tactic of claiming enough dependents so that no income tax would be withheld became more widespread as the Vietnam war continued. Often the tax refuser would make clear the moral grounds for the protest by listing, for example, “all the Vietnamese” as dependents. Refusing to pay for war by claiming excessive exemptions brought particularly strong response from the government. A number of people were prosecuted and imprisoned: Jim Shea, Karl Meyer, William Himmelbauer, Mark Riley, Ellis Rece, Carole Nelson, John Leininger, and Martha Tranquilli (a 64-year-old grandmother and nurse). The tax resistance movement continued after the war and grew to include both pacifists and non-pacifists who could no longer in conscience support the military priorities of the government.

From the newsletter of the Syracuse Peace Council

As more and more tax money was directed toward the [Reagan era] military buildup, many activists revived interest in war tax resistance. Protests were organized each year, and individual resisters tried a variety of means to deny the government money for war. In , demonstrations were held in Dallas, Atlanta, San Francisco, Los Angeles and other cities and 24 people were arrested at IRS offices in New York City. The following year, the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee was formed by the Center on Law and Pacifism, Conscience and Military Tax Campaign, WRL, Peacemakers and eighty local groups. featured the largest show of war tax resistance actions in , including Ralph Dull, an Ohio farmer and tax resister , who drove a truckload of grain to the IRS office as payment for his taxes. The IRS instituted a “frivolous returns” penalty to discourage the filing of returns with any but the requested information, and some resisters began an insurance fund, pooling their resources to pay fines and interest charges levied against fellow tax resisters.