Some historical and global examples of tax resistance → Spain → Ondárroa municipal tax strike, 2003–11

I briefly mentioned a tax resistance campaign by households in Ondárroa, in the Basque region of Spain. Here’s how that turned out (translation mine):

The Tax Strike in Ondárroa ends without facing taxes

200 families affiliated with the nationalist left stopped paying taxes in 2003, which had created a debt of more than €2.3 million

The tax gap opened in the municipal accounts of Ondárroa seems like it will close with this announcement. Nearly 200 families from Bilbao affiliated with the nationalist left who in started a powerful tax strike have decided to end their campaign of disobedience, promoted under the slogan “Eskubiderik ez, betebeharrik ez (no rights, no obligations).” The measure is not retroactive, as the Ondárroan advocates of tax resistance confirmed yesterday that they will only begin to pay taxes to the city “from after the rise to power of Bildu, which rules with an absolute majority. This is to say that they will not confront the accumulated taxes in the .

“We have no intention of paying the bills until the date we can be in process,” warned a spokesperson for the group yesterday. Tax resistance has had serious repercussions for the city revenue of Ondárroa, up to the point where the unpaid taxes totaled more than 2.3 million euros.

Dozens of families and local businesses declared themselves tax strikers to protest the judicial ban imposed on the nationalist left in the city [prohibiting them] from competing in the elections of and . The “tax resisters” took the initiative to censure the management that had led the city council during the last term, headed by Félix Aranbarri (PNV). The Corporation exit polls four years ago could not be established due to harassment by radicals of the elected councilors.

“Political rights”

The outlawed ANV claimed as its own mayor — with Unai Urruzuno at the front — and six counselors, in virtue of the invalid votes counted. “We will not pay until they return our political rights,” claimed the sympathizers of the old Batasuna.

At first, the militants of the nationalist left stopped paying taxes on trash, water, and sewage. But two years ago they decided to intensify the tax strike and would not pay other types of charges such as those for entry to the recreation center or those required for a building permit or for the road tax.

The new political scene that opened in the elections of , in which Bildu has obtained an absolute majority in Ondárroa, has encouraged the “resisters” to renew their contributions to the municipal coffers. “Our intention has never in any way been not to pay, but that the city be run democratically and that it respect the decision of the Ondárroans,” they said.

In the face of the refusal of the nationalist left to pay their bills, the Bilbao-Bizkaia Water Consortium told them by mail in of their intention to cut off the tap. The amount of the outstanding bills was around €200. But the campaign continued on.

The manager petitioned the Provincial Council of Bizkaia to help him collect more than 2 million euros that could not be raised . The statutory institution proceeded to collect some debts, while the tax resistance continued. The city management team tried to hire a company specializing in the collection and assessment of taxes and other such fees. However, it was impossible due to the radical pressure. Upon learning of the assignment of this work to the Bilbaoan firm Gesmunpal, the nationalist left spread slogans via Internet in favor of “civil disobedience,” as well as calls and letters against the company. Gesmunpal resigned.

I gave some examples of attacks directed at tax offices, some examples of attacks on the apparatus of taxation, some examples of tax resistance campaigns using particularly humiliating violent attacks against individual tax collectors, some examples of attacks directed at the property of tax collectors, some examples of direct violent attacks on individual tax collectors.

Today I’ll continue our look at the violent side of tax resistance campaigns by giving some examples of assaults and intimidation directed at collaborators with the tax system:

- In Paris during the French Revolution, legal proceedings against people who destroyed the tax offices were abandoned when neither the officers in charge of the investigation or the National Assembly itself had the courage to stand up to popular indignation and threats.

- Witnesses who were called to testify against the Fries Rebels “were generally very reluctant to give information, being afraid the insurgents would do them some injury.”

- In the Whiskey Rebellion, “William Richmond, who had given information against some of the rioters… had his barn burnt, with all the grain and hay which it contained…”

- During the Rebecca Riots, two or three hundred Rebeccaites met at an inn in Pontyberem and, during the course of the meeting, forced the innkeeper to swear not to admit the toll collector at the inn. In another example: “the dead body of Thomas Thomas… was found in a river near Brechfa! This man had been very much opposed to the Rebecca movement, and… had been to Carmarthen to make a complaint to the authorities against some Rebeccaites; on his return home that night he found his house, etc., on fire. Bearing this in mind, together with other circumstantial evidence, it is plain that he had some bitter enemies in the neighbourhood, and it was generally believed that he had been waylaid and murdered.” Thomas had on another occasion testified against his servant and had him jailed, and for this the Rebeccaites ransacked his house, destroying what they could.

- During the Tithe War in Ireland, resisters did what they could to prevent people from cooperating with attempt to seize and auction off resisters’ goods:

One clergyman had to import some sixty workers to help him take his tithes “in kind” from the farmers in his parish, “from distant counties, and at high wages, who yet were incapable of obtaining more than a small portion of tithes, being interrupted by a rabble — chiefly women — though men were lurking in the background to support them.”[I]t almost invariably happened that either the assembled spectators were afraid to bid, lest they should incur the vengeance of the peasantry, or else they stammered out such a low offer, that, when knocked down, the expenses of the sale would be found to exceed it. The same observation applies to the crops. Not one man in a hundred had the hardihood to declare himself the purchaser. Sometimes the parson, disgusted at the backwardness of bidders, and trying to remove it, would order the cattle twelve or twenty miles away in order to their being a second time put up for auction. But the locomotive progress of the beasts was always closely tracked, and means were taken to prevent either driver or beast receiving shelter or sustenance throughout the march.

- In colonial North Carolina during the Stamp Act agitation, “The stamp masters were seized and forced to swear they would have nothing to do with the stamps, and it being known when the vessel bringing the stamps would come up to Wilmington, Colonels Ashe and Waddell, having called out the militia from Brunswick and the adjoining counties to the number of some 700 men, seized the vessel and held her until her commander promised not to permit the stamps to be taken from her.”

- During the Reform Bill uprising in the , “Threats had been employed to prevent auctioneers from selling distrained goods; and an auctioneer in Bath had been obliged, in consequence of intimidation, to issue a handbill, in which he gave public notice, that he would not receive for sale any goods distrained for the non-payment of King’s Taxes.”

- Irish Household Tax resisters recently mobbed Ireland’s Minister for Public Expenditure and Reform, surrounding his car and chanting “fucking scumbag” Another politician who witnessed the event said: “In my view, there was an element of thuggery to it. Some of the protestors prevented him from getting out of the car park.”

- When Ondárroa tried to hire an outside debt collection company to go after resisters; “Upon learning of the assignment of this work to the Bilbaoan firm Gesmunpal, the nationalist left spread slogans via Internet in favor of ‘civil disobedience,’ as well as calls and letters against the company. Gesmunpal resigned.”

- During the Annuity Tax resistance movement in Edinburgh, a newspaper was sued for publicizing the names of the people who rented carts to the government for hauling away distrained goods — the grounds of the suit being that such publicity would be damaging to the business of the carters.

- The Poll Tax resistance movement in Thatcher’s Britain included attacks and threats directed at collaborators with the tax, for example:

- “Attacks and threats have been made against Bristol newsagents and shops where people can pay the Poll Tax. Windows have been smashed and graffiti daubed over businesses which have become agents for the Bristol-based company ‘Penalty Points.’ The firm installs special tills with its agents to collect the community charge on behalf of local authorities for a fee. Mr. Ross Hendry, a spokesman for the company… said ‘because of the attacks, one newsagent in Patchway has now declined taking an agency after a brick was thrown through his window. He said another newsagent in Bishoport Avenue, Hartclife had the words ‘Poll Tax scab’ and ‘you’re the first’ scrawled in white paint across his window. A Circle K store in Cardiff where the revolutionary scheme was launched on with 48 agents, had its door locks jammed with superglue.”

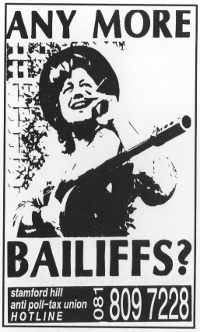

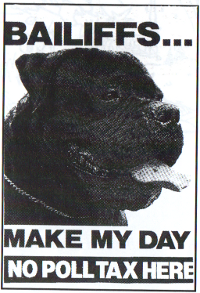

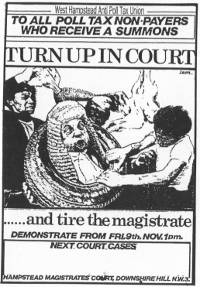

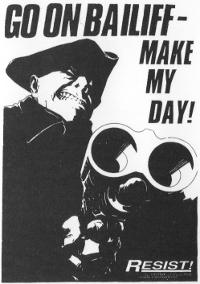

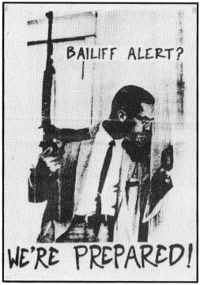

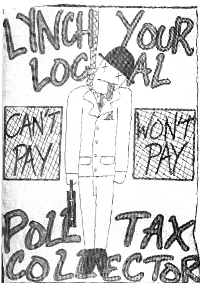

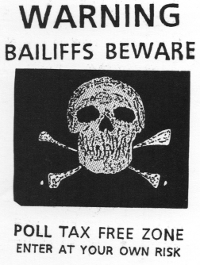

- Intimidation of bailiffs (people authorized to seize and sell property for tax arrears) was widespread: “Housing schemes and estates were plastered with posters. One showing a vicious dog, read ‘Bailiffs? Make my day!’ Another showing a picture of Malcolm X holding a machine gun looking out from behind the curtains, read: ‘Bailiffs we’re ready.’ A third showed a picture of a bailiff swinging in a noose. It read ‘Dead bailiffs don’t knock on doors.’ In some areas bailiffs and registration officers were photographed and their portraits were reproduced on posters which read ‘wanted’ and listed their ‘crimes.’ These images were extremely popular… People were used to seeing images of themselves in the role of victim. Now wherever they looked there were images of their adversaries in this role.”

- “Wherever the council registration officers went they were harassed.

In Glasgow violent threats drove canvasser Robert Stevenson to quit his job.

He was physically threatened twice in four weeks and continually harassed:

“…another canvasser… was ‘harassed by a gang.’ In this case, it was reported that:I’d just put the form through the door when this guy across in the garden opposite started shouting. He was sitting in the garden with about four others and they were all giving me dirty looks. He said that if I came back to collect the form I would need a tank for protection. I was in no doubt that they were serious. I didn’t finish my last street. I just chucked it.

“Following these reports, the Poll Tax registration officer admitted that ‘there had been at least four other incidents involving canvassers’ and… canvassers had been threatened (leaflets were grabbed from their hands). Already over two members of his staff had resigned because of fears about their personal safety.”Four or five youths cornered him in a close in Gairbraid Avenue and subjected him to abuse. A Strathclyde police spokesman revealed: “They said it was a ‘No Poll Tax Area’ and told the worker to get out, which he did.”

- Mayors and municipal councils resigned en masse to support the French wine-growers’ tax strike of , and, according to one account, “there have been threats to burn the property of those mayors failing to resign.”

- “Mr. Trueman, a Poll Tax snooper whose job was to call on people and badger them into filling the registration forms, [was] unable to cope with the abuse…

Mrs. Trueman found the corpse of her husband as she came back from shopping. Fred Trueman, 52, an employee of Bristol City, had hanged himself. “No-one can imagine what terrible pressure he had to work under,” she claimed. “He was sworn at and threatened; he couldn’t stand it any more.”

some of the posters with threatening messages aimed at bailiffs and other poll tax collaborators