One way tax resisters can foil the plans of the tax collectors is to send up the alarm when they’re on the way. Here are some examples:

- In rural Germany between the wars, a tax strike broke out, and when tax collectors came to distrain cattle from the resisters:

they blew the fire horn, and on the road they lit a fire of straw, the age-old sign that help is needed. Peasants ran from all sides towards the smoke.

- “Horning” was a legal term of art describing the process under which tax debtors could be imprisoned for defying the King (because it was normally prohibited at the time to imprison someone merely for being a debtor in default).

During the Edinburgh Annuity Tax resistance, one victim of this process declared “Horning! horning!

— by the powers! if they bring a horning against me, I’ll bring a horning against them.”:

When the King’s messenger-at-arms, as tipstaves are called in Scotland, brought his horning to the Cowgate, the Irishman, previously provided with a tremendous bullock’s horn, blew a blast “so loud and dread,” that it might have brought down the Castle wall; and a faction mustered as quickly as if it had sounded in the suburbs of Kilkenny. The messenger-at-arms took leave as rapidly as possible, and without making the charge of horning at this time.

- Poujadist tax rebels in France in

used this tactic: “Some priests ring church bells to warn of the arrival of the revenuers,” according to a Life magazine article on the movement.

A Montreal Gazette reporter said of Poujade’s Union for the Defence of Shopkeepers and Craftsmen:

The loudspeaker is its symbol and it all started in earnest one bright morning 18 months ago when a loudspeaker mounted on a truck brought awful tidings to the pleasant little town of St. Cere near Toulouse in south-west France.

“Attention,” it blared. “Attention. The tax inspector is in town.”

There was a rumbling sound as the steel curtains with which French shops are shuttered at night were rolled down all over St. Cere. …

The tax inspector rapped on steel curtain after steel curtain, demanding to be let in to see the books. Nowhere did he get an answer. When they found that even the bistros were locked, the hapless inspector and his guards gave up their mission and beat a humble retreat from St. Cere.

The triumph of St. Cere lit the fires of rebellion in the hearts of tax-ridden shopkeepers all over France. Poujade was suddenly a national figure and he lost no time in organizing his Union to spread the message of the loudspeakers and the steel curtains.

- More recently, in Greece, when tax official Nikos Maitos took a team of inspectors to the island of Naxos to hunt for tax evaders, “a local radio station broadcast his license plate number to warn residents.”

- During the Bardoli satyagraha, tax collectors and other government enforcers were tracked by the resisters, who warned villagers when they were on the way.

Resister Govardhandas Chokhavala said, “We have provided our volunteers with drums and conches, and the moment they sight a Government servant, the drum or the conch gives the alarm.

That is work which is after the heart of these youngsters.”

Some other notes from The Story of Bardoli read:

[E]very village had its volunteers ready with their bugles or drums which Were pressed into aid as soon as they caught sight of the Talati and Patel out on their japti [attachment] depredations

The youngsters on duty announced [the Collector’s] arrival by a hearty beating of their drums. and all the doors were closed.

[T]he other [new legal] notification which was over the signature of the District Superintendent of Police prohibited the beating of drums, playing music, or blowing conches or horns on or near public roads or public places or Government buildings.

Some boys were arrested, tried, and imprisoned for nothing more than keeping a watchful eye on a government building from across the street.Some of them had to post themselves at and keep a strict watch over the various approaches to the village, and no sooner was a japti party sighted or the whank of a car heard, than they were to be on their alert, and the warning of the fact to be given to the village people. Some of them had always like sleuth hounds to be on the trail of the Government officials. Their business was to scent their plans and warn the village people against their machinations.

- Tax resisters in Alwar, India in used this system: “The paths are blocked by huge boulders and at intervals along the hills remote from the towns are watchers with giant tom-toms which are heard for five miles, giving warning of the approach of troops or the revenue collectors.”

- The horn became the symbol of the Rebeccaite uprising in Wales, because of incidents like this one:

The constables then went towards Talog; but when on their way there they heard the sound of a horn, and immediately between two and three hundred persons assembled together, with their faces blackened, some dressed in women’s caps, and others with their coats turned so as to be completely disguised — armed with scythes, crowbars and all manner of destructive weapons which they could lay their hands on. After cheering the constables, they defied them to do their duty. The latter had no alternative but to return to town without executing their warrants. The women were seen running in all directions to alarm their neighbours; and some hundreds were concealed behind the hedges, intending to appear if their services were required. The entire district seemed to be aroused, and awaiting the arrival of the constables, who were going to levy on the goods of John Harris of Talog Mill for the amount of the fine and costs imposed upon him by the magistrates. There could not have been less than two hundred persons assembled to resist the execution of process, and vast numbers were flocking from all quarters, in response to the blowing of a horn, the signal of the Rebeccaites to repair thither. Various mounted messengers were scouring the country and sounding the trumpet of alarm.

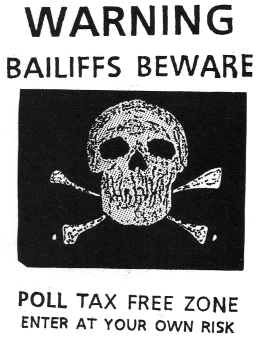

- During the poll tax rebellion in Thatcher’s Britain, resisters tracked and shadowed bailiffs, and declared certain areas to be bailiff “no-go” zones, with watchouts established to raise the alarm if any approached.

They first modeled this approach on tactics used in South African townships during the anti-apartheid resistance there, and then improvised from there:

Throughout Britain, city-wide bailiff busting groups were formed. Activists in Edinburgh formed a group called “Scum-busters” which was equipped with CB radios, and squadrons of cars. Telephone trees were organised; bailiff companies were monitored; their car registration numbers were taken and distributed to activists in all the local areas. Camden, in London, followed their example in :

We have organised a rota so that we know who and when people are available to do whatever shift. We have organised a “knock up system” giving people different responsibilities for knocking up each part of the estate when the bailiffs are spotted. Telephone trees have also been established. We have approached a couple of mini-cab firms who have agreed to be bailiff spotters.…