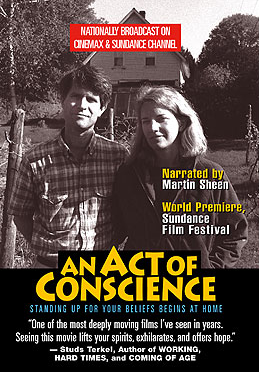

Rebecca and Her Daughters

Being a History of the Agrarian Disturbances in Wales Known as “The Rebecca Riots”

by the late

Henry Tobit Evans, J.P.

Printed by the Educational Publishing Company, Ltd. Trade Street, Cardiff

Foreword

The editing of this History of the Rebecca Riots, written by my late father, has been to me a very pleasing and at the same time a very sorrowful task; pleasing, inasmuch as I was able to gather together his copious notes, the result of years of research, sorrowful, insomuch that he was not spared to complete the work, for doubtless then the book would have assumed a more polished style.

The arrangement of the notes into chapters has proved difficult. It is with diffidence that I let the MS. go out of my hands, for I am fully conscious of its shortcomings, yet I trust that the book will meet with the approval of those best qualified to judge of its merit and worth.

My subscribers I heartily thank. Many a cheery message have I received from them which has helped me over black days when “Rebecca” was unusually hard to deal with. A kind word goes far — may the critics remember that when they judge.

G. T. E.

Trewylan, Sarnau Henllan, Cardiganshire,

Contents

In editing this History of the Rebecca Riots the following books, periodicals, newspapers (among others) for the period have been consulted:

- The Report of the Commissioners of Inquiry for South Wales.

- The Rebecca Rioter, a novel, by Miss E. A. Dillwyn.

- Y Diwygiwr.

- Y Gwladgarwr.

- Y Bedyddiwr.

- Seren Comer.

- Yr Haul.

- The Welshman.

- Gweithiau, “S. R.”

- The Red Dragon. Vol. Ⅺ.

- The files of the following newspapers:

- The Times.

- The Standard.

- The Cambrian.

- The Carmarthen Journal.

- The Bristol Mercury.

Introduction

Many interesting and romantic stories are frequently related about “Rebecca” and her “daughters,” but the actual exploits of this renowned band have not, so far as is known, been collected and set down in book-form.

Nothing has been published except the Report of the Commissioners for , a novel called The Rebecca Rioter, a few scattered articles in various publications, and the reports of the riots in the newspapers of the period, to give any idea of the wave of indignation which spread through Wales almost a century ago a wave which rose higher and higher, till it broke at last in open rebellion against the oppression of the Government and the tyranny of those in authority.

What were the “Riots”? What were the causes? And who were “Rebecca” and her “daughters”? are some of the questions which naturally arise in the minds of those who are strangers to the history of this rebellion against the despotism of those times, and whose forebears were not participators in the revolt.

Wales is generally regarded as a very peaceful country, and its people as a peace-loving nation, who prefer to suffer wrong and indignity with meekness and resignation, rather than to boldly retaliate and proclaim their rights in unmistakable manner, and when reading the accounts of these wonderful riots, one is easily persuaded that it is an account of passionate Ireland in the throes of the Land League agitation, rather than of quiet, peaceful Wales.

“Rebecca” and her “daughters,” realising that they had no power to bring about reform by moral suasion and legitimate agitation, resorted to open revolt against their oppressors, and took the law into their own hands. This cannot be glossed over; their action may not be approved of, nevertheless they succeeded in drawing attention to the grievances from which they sought to be rid, and undoubtedly from their point of view and the welfare of their children, the means justified the end.

The riots were but a part of the agrarian disturbances which took place in various parts of the country. In some districts they took the form of the Chartist Riots, while the revolt of the peasants in Wales has become known as the Rebecca Riots. All the disturbances had a common root; they sprang from the same great grievance, but each district had its own particular form of rebellion, just as each district had its own distinctions and characteristics.

It has been well said1 that the Chartists might be roughly divided into three classes — the political Chartists, the social Chartists, and the Chartists of vague discontent, who joined the movement because they were wretched and felt angry. Truly this might be taken as a description of the Rebeccaites. We come across the exploits of the political Rebeccaites, who rebelled against the operation of the Poor Law Amendment Act, the weak administration of Justice by local magistrates, and agitated unceasingly for Free Food. The social Rebeccaites sought to better the lot of the agricultural labourer by sustaining a revolt against the unequal distribution of rent charges, the increase in the amount payable for tithes, and the increasing cost of all necessaries of life; for the excessive tolls exacted from the farmers naturally had their counterpart in the higher cost of all commodities. The grievances of the Rebeccaites of vague discontent were legion, and these malcontents of vague ideas and loose principles tended eventually to lessen the effectiveness of the greater movement, and weakened the case of those leaders who, at great personal sacrifice of life and freedom, willingly placed themselves at the head of a movement which their principles and their convictions forced them to start, and which they honestly believed to be their only method of redressing their grievances. Some people have a hazy idea, due to the gathering mist of passing time, that the Rebecca Riots were merely a nightly gambol of reckless spirits let loose on the countryside, whose sole object was to enjoy themselves in uproarious fashion a boisterous gang going about destroying toll-gates for a pastime, and firing toll-houses for a recreation. This is not so; the Rebeccaites were instigated to their revolt by strong convictions of their grievances, and they were firmly determined to do away with the monster of tyranny, which they regarded as sucking their life blood. The attacks on the toll-gates were undertaken simply because it was a glaring fact forced into their minds every day of their lives that the heavy tolls demanded from them on all goods were the direct cause of the high cost of living in their districts; therefore, though nominally a revolt against the toll-gates, really it was a great movement among the peasantry of South and West Wales for untaxed food and cheaper living. It was thus part of the great epidemic of revolt which swept the country, finding its counterparts in the Chartist Riots in Monmouthshire, the Anti-Corn Law Agitation in England, and the cry of Ireland after the failure of the potato crop. It was the spirit of democracy wearied of its chains and bonds of slavery, crying aloud for freedom and redress.

Of all the counties affected, Glamorganshire alone at that time possessed any paid constabulary, or any force that could be of service. The other counties relied upon the services of pensioners, or special constables sworn in on any particular occasion, therefore when the riots were at their height, they were obliged to have recourse to the military for help to protect property and lives.

Finding that restoring gates, rebuilding houses, and offering large rewards for the apprehension of the rioters failed to produce any satisfactory results, the trustees lost heart, and roads were left free of toll. This was the popular triumph.

Undoubtedly the origin of all this turbulence was the resistance to the payment of turnpike tolls. The farmers complained of the expense of paying these tolls, and when it is recollected that in Carmarthenshire alone there were eleven toll-bars on nineteen miles of road, besides additional bars on the by-roads, it is apparent to everyone that they had good reason for complaint. They also suspected that the proceeds from the tolls were not fairly expended on the roads.

Among the subjects of complaints in the meetings on hillsides, by mountain streams, and at many out-of-the-way places, held for the discussion of grievances, were the following:

- Tolls had to be paid every third time of passing.

- Mismanagement of funds applicable to turnpike gates.

- Amount of payment of tolls.

- Illegal demands of certain toll-collectors.

- Increase in the amount payable for tithes.

- Unequal distribution of rent charges.

- Operation of the Poor Law Amendment Act.

- Weak administration of justice by local magistrates.

- Excessive cost of recovery of small debts.

- Multiplication of side-bars by private individuals.

- Monoglot Englishmen holding office in Wales.

- Increased County Rates.

About this time () and before the introduction of railways, the magistrates in these districts had set themselves to make new roads as well as to widen and improve the gradients of the old ones; to pay the cost of these improvements, they had increased the number of the turnpike gates in such a manner that there was scarcely a town or village that was not approached by a gate.

The turnpike roads were held under separate trusts, and the trustees found it necessary, in order to protect the interest of the tallyholders, to place their gates near the confines of their respective districts, so as to prevent persons from other districts travelling over their roads free of charge.

It therefore frequently happened that persons living and travelling within any given district, were only charged one toll for the use of a considerable length of the road, while those living on the borders, and having occasion to travel out of the district, had frequently to pay at two gates within a comparatively short distance.

There were five different trusts leading into the town of Carmarthen, and any person passing through the town in a particular direction had to pay at three turnpike gates in a distance of three miles.

About the year a turnpike road was made between Pembroke and Carmarthen, with the intention of gaining pedestrians along it between London and Ireland. The promoters of the scheme were, however, disappointed with the result, inasmuch as they left only thirty-two miles of road between Carmarthen and Milford as a road to the mail-coach, which often carried but three or four travellers in the day. Owing to this, not enough money was raised to pay the interest on the capital expended, much less to keep the road in repair.

The trustees had a right to set up toll-gates on lanes, and to throw the costs of the main roads on the parishes, and they exercised that right to the full. The toll on the road amounted to 12s. 6d. for every market cart for thirteen miles. Besides this the people had to repair the roads.

At the instigation of some Englishmen, four additional gates were demanded on parish roads near Whitland, in order to create an increased source of revenue. These toll-gates were accordingly erected, and completed by . They stood at Cefnbralam crossroads, Llanfallteg, Cwmfelinboeth, and Pantycaws near Efailwen.

After they were opened, farmers were compelled to pay heavy taxes on the haulage of lime and culm (the ordinary fuel in Wales), over roads maintained by themselves, and hitherto free. To redress their grievances, the farmers upon finding that their petitions were not receiving desirable consideration, formed a League, and after holding conferences at different places, it was agreed that such tyranny could no longer be tolerated and they decided to remove the oppression.

About six o’clock one evening in the summer of , a large number of farmers, chiefly from the neighbourhood of Efailwen and Llandyssilio, assembled at Whitland, and after exchanging their views on the matter and expressing some threatening epithets in reference to the trustees, they decided to demolish the four toll-gates. A movement was made towards Cwmfelinboeth, accompanied by discordant music and disturbances, and the four gates were that night destroyed without the slightest opposition or interference being made. The rioters were disguised, and had their faces blackened; but they had not then adopted the name “Rebecca.” It was feared that these gates would be re-erected; but through the instrumentality of Mr. Powell of Maesgwynne, better counsel prevailed. It was hoped that the high feeling which prevailed among the farmers against the payment of tolls would gradually cool down, but unfortunately this outbreak was only a forerunner of further agitation and tumults. For a time peace and goodwill appeared to reign, but owing to the number of toll-gates and the amount of toll paid by some farmers, disturbances and agitations again took the field, and for a long time predominated. Eventually the League was revived, and secret meetings were called in West Carmarthenshire and East Pembrokeshire, the most enlightened members of the Society being selected to go about expounding their policy, and to deal with the imposition and injustice of the trustees.

To the neighbourhood of Efailwen must be given the first and foremost place in connection with the formation of the Rebecca Movement, and to the people of that district must be given the credit of providing the movement with a leader. It was decided at Efailwen and Whitland, that the rioters should be clothed in women’s dresses with blackened faces, and fern in their white caps. Their arms were to consist of sticks, pikes, spades, hatchets, old swords, guns, in fact any weapon they could get hold of. The leader, to be called “Rebecca,” was invariably to be mounted and accompanied by a bodyguard. All their doings were to be conducted under the superintendence of “Mother Rebecca,” and all arrangements and commands were to be made and given by her. Many guesses were hazarded on the subject of “Rebecca”; “Rebecca” was elusive, “Rebecca” was unknown. Some2 suggested “she was a disappointed provincial barrister,” others asserted that “she was a political agitator bent on making the abolition of tolls the seventh point in the Chartist programme.” A writer of the period, dealing with this subject very pointedly, remarks: “The supposed sole chief and director of the campaign must have been gifted with ubiquity, for Rebecca was in three of four counties at the same moment.”

“Methinks there be two Richmonds in the field.”

The truth is, that each district had its own Rebecca, who planned the various enterprises, and who was recognised as chief by the rest of the band. Whether the districts worked independently or had a common centre of action is uncertain.

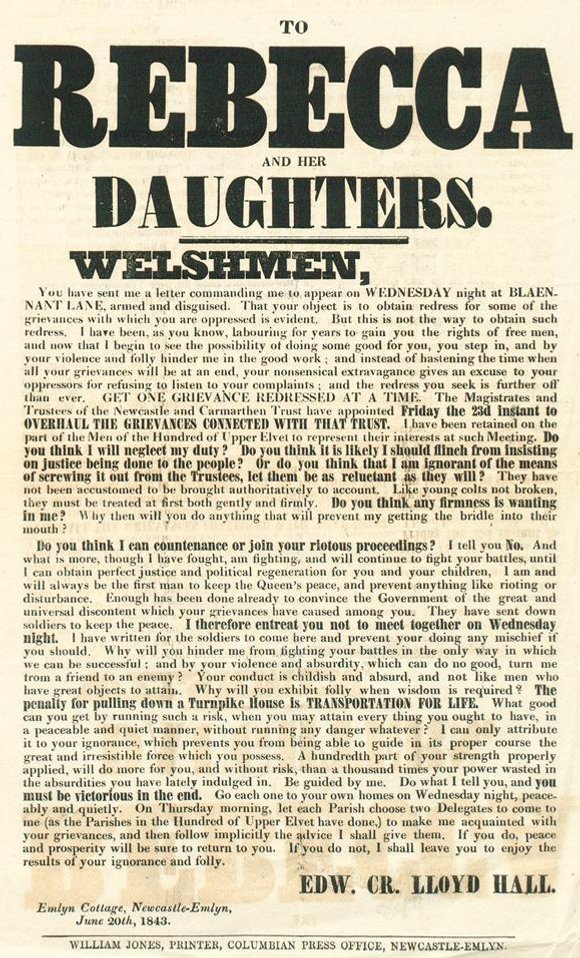

It is intensely interesting to read the letters and the proclamations issued by “Rebecca.” They are written either in colloquial Welsh, with complete unconcern as to grammar and spelling; or in English, which would be a literal rendering of a similar expression in the Welsh language.

Some of these letters are genuine enough in their mistakes of grammar, and orthography; but one is convinced when reading other manifestos and circulars, that they are the work of a person who seeks to hide his identity under a cloak of ignorance. Some of the leaders were unquestionably men of position and learning, for their political knowledge and their legal learning as expressed in the garb of bad Welsh and worse English, proclaim them as men above the ordinary peasant. Their thoughts, though expressed in uncouth terms, betray the political thinker and the social reformer.

In this connection it is interesting to note that Mr. Hugh Williams, a solicitor, residing and practising at St. Clears, and a native of Machynlleth, took a very active part in the Rebecca movement, and did all the legal work for the rioters, also drafting various petitions for them. He was a prominent member of the Chartist movement, acting as their solicitor, and he defended the prisoners at Welshpool Assizes in , for taking part in the Chartist Riots. He rendered similar services to the Rebecca prisoners gratuitously; but was eventually reported to the Lord Chancellor and struck off the Rolls.

He, however, continued to do a considerable amount of legal work, and whenever it became necessary for him to appear in court, he invariably employed Mr. Thomas Davies, solicitor, Carmarthen (who had been articled to him), to appear for him. He was looked upon as one of the ablest and keenest solicitors in the Principality. For many years he lived at St. Clears, but at last removed to Ferryside, where he died.

The first leader, who was present at Efailwen and Whitland, was one of the most important persons in the whole movement, and no apology is needed for a detailed reference to him.

Thomas Rees, alias “Twm Carnabwth,” residing at a place called “Carnabwth,” in the parish of Mynachlogddu, in the county of Pembroke, was, in , made a leader of the Rebecca rioters. He was then about thirty-six years of age, and considerably above middle stature, possessing great muscular power, and was a noted pugilist. He frequently gave ample proof of his powers at fairs or local festivities, where fights and other disturbances so often took place; his services at those places were frequently in requisition to separate the combatants. When Twm was chosen leader, and it was decided that the rioters should wear women’s garments, considerable trouble was experienced in procuring a gown large enough to fit him; several gowns were borrowed, but to no purpose, and it was feared that a new one would have to be made. At last, however, the rioters came across a tall and stout old maid named “Rebecca,” and after undergoing some alterations, her dress was made to fit Thomas Rees tolerably well. From this circumstance the name Rebecca was adopted, and not, as some say, from having taken Genesis ⅹⅹⅳ. 603 as a motto.

It was a curious coincidence that at Efailwen Gate, the toll-keeper’s wife should be known as “Becca,” her full name being Rebecca Davies. Thomas Davies, her husband, was unable to attend to the gate, owing to his vocation (that of a coachman) compelling his frequent absence from home; consequently, that duty fell on his wife’s shoulders. Some people assert that the rioters assumed their “nom de guerre” in derision of her valiant efforts to defend Efailwen Gate from their attack.

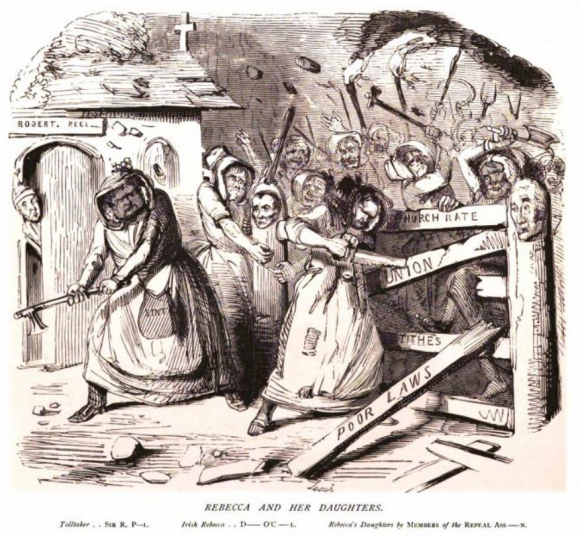

Thomas Rees distinguished himself greatly as a leader, and succeeded beyond measure in destroying the toll-gates which were so numerous. He soon established a name for himself in the agitation. Most of the followers wore bet-gowns (the peasant dress of Welsh women), and were frequently called Mary, Jane, or Nelly, after the names of the women whose gowns they wore. “Rebecca” pretended to be the “Mother,” and the others her “daughters”; and they addressed each other as such when attacking the toll-gates.

When more than one attacking party was organised for the same evening, another leader had to be chosen; and he, of course, was styled “Rebecca” for that occasion.

After the Riots were at last put down, Thomas Rees continued his hold over the district in which he lived, and whenever a pugilist visited the place, he was always put up as champion, invariably giving a good account of himself in all the combats in which he took part.

In , a hawker, named Gabriel Davies, twenty-two years of age, who lived at Carmarthen, came to the district. He took up his abode at Pentregalar public-house, which was on the main road between Crymych and Narberth. He was very strong, and his reputation as a pugilist had reached the district long before him. After having been at Pentregalar for several nights, a quarrel arose between him and his landlord, in consequence of which he removed to a public-house called “The Scamber Inn,” situated about a mile nearer Llandyssilio. The landlord of Pentregalar was much annoyed at this, and declared he would have his revenge on him. There also existed considerable feeling in the district as to the superiority of Gabriel and Twm Carnabwth in the pugilistic world. In order to decide which was really entitled to the coveted honour of being champion, it was arranged to bring about a rupture between the two men if possible.

The landlord of Pentregalar Inn was deputed to wait on Twm; the following day he went in search of him, and brought him to his own house, where, after giving him some alcoholic drink, he offered Twm a gallon of beer if he would give Gabriel Davies a sound thrashing. Being thirsty, and believing himself to be the better man, Twm at once accepted the offer, and proceeded to the Scamber Inn. Gabriel was kept in total darkness as to what was going on; though an occasional fight was more delicious to his palate than a good breakfast, yet, as the fighting capabilities of Twm were well known, it was more than probable had the hawker been informed of Twm’s object, he would have beaten a hasty retreat to some secluded spot, so as to obviate the necessity of coming in contact with the Welsh “lion.” Such intimation, however, was not given, and early in the afternoon of that day, Twm Carnabwth entered the Scamber Inn and called for a pint of beer. Gabriel, who happened to be sitting down near the fireplace, wished him “Good afternoon,” and endeavoured to carry on a conversation with him, but Twm’s repulsive demeanour soon made it clear that he was not of the same sociable turn of mind. The latter next tried to pick a quarrel; but Gabriel was too old a bird to be drawn into his net, and instead of retaliating, sang his praises as a leader and a fighter, and wound up with an appeal to drink beer and be happy. Quart after quart was called for by Gabriel, but instead of indulging in it too freely himself, he quietly disposed of his share by pouring it into a corner close by.

Twm on the other hand continued to drink, and instead of exercising the necessary precaution against over-indulgence, imbibed too freely of the beverage, and eventually got intoxicated. When St. Peter’s boy observed the state of his antagonist, he thought that the time had come when he could take a more active part, and at once threw down the gauntlet. A fierce fight ensued, and owing to Twm’s drunken condition, he was soon thrown to the ground, one of his eyes having been gouged out by Gabriel. The combatants were then separated, and the fallen warrior was taken home. He suffered great pain for some time afterwards, and as inflammation set in his life for a time was despaired of. Gradually he recovered, after which he joined the Baptist Church at Bethel Mynachlogddu, where he remained a zealous member till his death. It will therefore be seen that Gabriel Davies, though unwittingly, was the means of converting one sinner from being a terror and a drunkard, to be a decent member of society. After his conversion he became a very genial and benevolent person, highly respected by all his acquaintances.

On , Thomas Rees, at the age of seventy years, was found dead in the garden adjoining his own house. This house was situated on the bank of a tributary to the Cleddau river, at the foot of Prescelly Top, Pembrokeshire. It is supposed that his death was caused by a fit of apoplexy or a stroke while gathering vegetables for dinner. His remains were interred at Bethel burial ground on .

A tombstone was subsequently erected over his grave, and on it is the following inscription:

Er cof am

Thomas Rees, Trial4

Mynachlogddu;

Bu farw

Yn 70 mlwydd oed.

Nid oes neb ond Duw yn gwybod

Beth a ddigwydd mewn diwarnod;

Wrth gyrchu bresych at fy nghinio

Daeth angeu i fy ngardd i’m taro.

Many strange and weird stories are related about the person of Rebecca. People drew largely on the imagination when describing the night attacks of the dreaded lady. Yet the manner of attack and the dress of Rebecca and her Daughters were in the main alike on all occasions.

As to the “form and mode” of attack, the following vivid pen-picture5 is a good description:

The secret was well kept, no sign of the time and place of the meditated descent was allowed to transpire. All was still and undisturbed in the vicinity of the doomed toll-gate, until a wild concert of horns and guns in the dead of night and the clatter of horses’ hoofs, announced to the startled toll-keeper his “occupation gone.” With soldier-like promptitude and decision, the work was commenced; no idle parleying, no irrelevant desire of plunder or revenge divided their attention or embroiled their proceedings. They came to destroy the turnpike and they did it as fast as saws, and pickaxes, and strong arms could accomplish the task.

No elfish troop at their pranks of mischief ever worked so deftly beneath the moonlight; stroke after stroke was plied unceasingly, until in a space which might be reckoned by minutes from the time when the first wild notes of their rebel music had heralded the attack, the stalwart oak posts were sawn asunder at their base, the strong gate was in billets, and the substantial little dwelling, in which not half an hour before the collector and his family were quietly slumbering, had become a shapeless pile of stones or brick-bats at the wayside.

Meantime all the movements of the assailants had been directed by a leader mounted and disguised like his body-guard in female attire, and having like them his face blackened, and shaded by a bonnet or by flowing curls, or other headgear. … Day comes and the face of the country wears its accustomed aspect.

Rebecca and her daughters becoming accustomed to notoriety, and reckless in the face of danger, undertook to redress all wrongs, and put themselves in the role of judges, determining the course of action in connection with many grievances. In the pages following will be found many such instances, some of the most interesting being the care that ’Becca took of bastard children. The following rather gruesome story is a peculiar instance of Rebecca’s interference in order to right a seeming wrong, and to settle a point which for years had given occasion to doubt and misgiving.

In , a parishioner of Trelech, of the name of William Jones, who lived on his own farm, Croes Ifan, of the value of about £80 a year, died and was buried in the parish churchyard. He left a lonely widow behind him. Apparently there was a marriage settlement between them.

William Jones’s brother, thinking that he was the rightful heir, took possession immediately on William’s death, having understood that he was to pay a yearly sum to the widow. Some little time after the burial he asked the widow for all the deeds of the place, when she informed him that she knew nothing about them, and that the last she had seen of them was in a red handkerchief ’neath her husband’s arm shortly before he died. They failed to proceed any further, and things quieted down somewhat. In a short time a rumour passed through the neighbourhood that the deeds were in the coffin, and the hubbub occasioned was great. The brother talked of opening the grave or vault, and demanded from the widow the key of the iron railings which surrounded it; but she refused to give it up. This naturally strengthened the opinion that the deeds were in the coffin; but the brother, having no substantial evidence, gave up the idea of opening the grave.

Not very long after, another rumour arose about the deeds, and in order to settle the uncertainty about their location in the coffin, on , ’Becca and her children resorted to the graveyard of the church of Trelech and Bettws. Rushing towards the grave or vault, they wrenched off the iron railings which surrounded it, opened it, as well as the coffin, and made a thorough search for the deeds; the body was mixed up and the whole place left in the greatest disorder. They disappeared secretly, leaving the grave and coffin open. Having spent some hours in a search for the missing deeds which were not discovered,6 and having done much damage to the body, they evidently made a hurried retreat. It is impossible to find words strong enough to condemn their inhuman actions in disturbing the repose of the dead, and inflicting so grievous a wound on the feelings of the living.

Rebecca after her first successes at Efailwen and Whitland, made the necessary arrangements for attacking Trefechan or Trevaughan near Whitland, on , and without much ceremony demolished the gate. “Nothing succeeds like success,” and ’Becca’s daughters increased in number and power daily. Toll-gates disappeared nightly, but, strange to say, not a single capture was made until the end of May in that year. Persons more unscrupulous than the original malcontents were soon associated with the disturbances, which speedily assumed a serious aspect, culminating in threatening letters, theft, arson, and even murder!

Many of the country gentlemen appealed to the better feelings of the people, but unfortunately without the desired effect.

The story of the attack on Efailwen Gate is typical of other attacks. The gate, which was a wooden one, was cut down with hatchets, saws, and bars, and an attempt was made to burn down the house, but unsuccessfully. The gate-posts were cut down, carried away, and thrown into the river Cleddau. Shortly after, another gate was erected, which was made of wood, plated with iron, so as to prevent its being cut down with hatchets and saws, whilst the posts were made of cast-iron.

An account is given in the history of the demolition of gate after gate, with the doings of Rebecca on each occasion. One of the most serious of the disturbances occurred at Carmarthen on , which culminated in the attack on the Workhouse, where, on the arrival of the soldiery, several of the Rebeccaites were taken prisoners within the Workhouse walls.

We follow them to Cardigan, where they attacked the Rhos Gate on the road leading to Aberayron, on . There were present many of the town people and inhabitants of the vicinity, who were anxious to see Rebecca, because it was believed she was supernatural, and totally unlike others in appearance.

She was accompanied by about two hundred of her daughters, and when approaching the Rhos Gate called out, “Gate! Gate!” There was no one within, for the woman previously in charge had removed her furniture, and had also gone herself to a public-house called the “Victoria Arms.” Being the keeper of both toll-house and public-house, the latter proved to be of valuable service on that occasion.

Rebecca and some of her children had their faces blackened, whilst others had yellow coloured faces. They were dressed in female attire, and among them were both Welsh and English representatives.

The gate and walls were totally demolished in about fifteen minutes; but the house, which was new and very strong, took them an hour to destroy. At the end of that time it looked very much like an old monastery — a little up and a great deal down.

From here, the rioters marched through the main street of the town, shouting, “Powder! Powder!” They proceeded to Rhydyfuwch Gate, which was about three-quarters of a mile from the town on the Newcastle road. They pulled down the gate on the Llangoedmore road, but left the gate on the coach-road unmolested.

They then departed, appearing to be satisfied with the work they had accomplished.

was market day in Cardigan, and every one who drove in was exempted from paying the usual toll, except those who came over the coach-road. The people, looking at things from that point of view, were filled with Rebeccaite enthusiasm. On that day nothing was heard at public-houses but proposals of good health and long life to Rebecca.7

New Inn Gate, situated about half-way between Cardigan and Aberayron, was demolished on . It was put up the following day, and destroyed again the night of , as also were Aberceri and Henhafod, two bars near Newcastle Emlyn. Rebecca had about 250 followers, and expected a contingent of 700 men from Carmarthenshire to join her, but Mr. Hall (afterwards Mr. FitzWilliams) succeeded in dissuading them from coming. On that night, Rebecca again visited Efailwen, and finding the task of demolishing the gate a difficult one, without having the necessary implements at her disposal, sent two of the company to the blacksmith’s shop to demand sledges from the smith, Morris Davies. He at first refused, but upon their threatening to pull down the smithy, he threw the key of his shop out of his window to them. The sledges were then brought out, and the posts and gate smashed to atoms. The rioters then dug under the walls, and the toll-house was completely destroyed.

Subsequently the authorities were informed that sledges from Efailwen smithy had been used, and that a farmer named John Davies, residing at Plas Llangledwen had said something relative to the demand made at the smithy. Enquiries were made with a view to procuring sufficient evidence to justify proceedings being taken against someone for the damage, but the blacksmith and John Davies denied all knowledge of the fact. They were in consequence taken into custody, and lodged in Carmarthen Gaol. There they were kept for three months awaiting their trial, but eventually they were discharged.

On the same date a chain was placed across the road, where the Rhos Toll-gate had formerly stood at Cardigan; but almost before it was completed Rebecca and her daughters with picks, shovels, etc., pulled the posts from the ground, and then disappeared. Other attempts were made to put up the chain, but on each occasion were frustrated.8

On , some soldiers arrived at Cardigan, and of these sixty were despatched to Newcastle Emlyn Workhouse. The remaining sixty were quartered at the Free School, Cardigan; some fifty constables were also brought to Cardigan in addition to the twenty already stationed there. By this time it was dangerous to say anything concerning the riots, and people had to be on their guard. One man in a joke said to a toll-keeper’s wife that Rebecca was again on the road; though he meant nothing, he had to go before the magistrates, and he had considerable difficulty in keeping out of the county gaol.

Talog, near Carmarthen, was the scene of a riot on , while on Pontarllechan Toll-house was destroyed. The house of David Harries, Pantyfenwas, was invaded by ’Becca and her children on .

In spite of the many disturbances and the serious riots that occurred, Rebecca always managed to carry on her work so very quietly that even the neighbours were kept in total ignorance of her movements until her arrival on the scene of action. The attack, on , on Pumpsaint Toll-gate, which stood between Lampeter and Llandovery, showed that Rebecca could be recklessly daring; for it was carried out while the cavalry were fast approaching the place. Yet, it is worthy of note, that during all this period of turmoil and rioting, Rebecca and her daughters were strict Sabbatarians. With one exception, we have no accounts of attacks being made on any form of property, or rebellion against any grievance, taking place on the Lord’s Day.

About , a toll-gate some five miles from Llandovery on the Builth road, was demolished. The toll-keeper stood his ground firmly for some time against the intruders; but at last finding that the better part of valour would be to run, he did so without further ceremony. Eight persons were afterwards taken up on suspicion, and were detained for one night, but were subsequently discharged. During the time these persons were in custody, Bronfelin Toll-gate and house were destroyed and afterwards set on fire.

It was this difficulty in laying hands upon the real perpetrators, that nonplussed the authorities. We read continually of persons being arrested on suspicion, and eventually being set free, because of the great difficulty in bringing home the accusation. On , we find posters being circulated, offering a reward of £500 (!) for the discovery of the ringleader in the riot which had occurred at Pontyberem on . This offer shows that the authorities placed a very high value on the ringleaders; but at the same time it clearly illustrates either the inadequacy or the incompetence of the forces whose particular work was to quell the disturbances, and consequently they announced the bribe of £500, hoping that some treacherous companion might sell the leader to them for a bag of gold.

After a series of serious riots had taken place, among which were a riot on at Coalbrook Llanon; at Llandebie, where the house of Mr. Rees was demolished on the ; and the destroying of Pentrebach Gate on , we notice that Rebecca, becoming increasingly bold and daring, committed arson at Pantycerrig, attacked Dolauhirion Gate on the , Nantgwyn on , and on a place called Pound.

So serious had these constant riots become (for Rebecca was not content now with destroying the toll-gate, but had an increasing love of incendiarism) that detachments of soldiers and London police were drafted into different parts of the country, and during police forces were established for the counties of Carmarthen and Cardigan.

Among the many grievances dealt with by the rioters was the question of free rivers, and on Rebecca and her daughters proceeded towards Castell Maelgwyn, Llechryd, in full force. After removing a salmon weir, they made for the house, Fortunately Mr. Gower, the owner, happened to be in London, attending to his duties as a Director of the Bank of England. When this became known, ’Becca at once ordered her daughters to retire. They left without committing any damage, neither did they hurt anyone at the house.

During this period, all the gates and bars in the Whitland, Tivyside, and Brechfa Trusts were destroyed. Two gates only out of the twenty-one survived in the Three Commotts Trust, whilst between seventy and eighty gates out of about one hundred and twenty were destroyed in Carmarthenshire. Only nine were left standing out of twenty-two in Cardiganshire.

On , the dead body of Thomas Thomas, Pantycerrig, in the parish of Llanfihangel-rhos-y-corn, was found in a river near Brechfa! This man had been very much opposed to the Rebecca movement, and on he had been to Carmarthen to make a complaint to the authorities against some Rebeccaites; on his return home that night he found his house, etc., on fire. Bearing this in mind, together with other circumstantial evidence, it is plain that he had some bitter enemies in the neighbourhood, and it was generally believed that he had been waylaid and murdered. The stream of water where the body was found, was so shallow that his head and right arm could be easily seen. When examined, a deep wound was found on the left temple, and there were other marks on different parts of the body. The deceased had taken out warrants for the arrest of two young men sons of a blacksmith residing at Brechfa for stealing sheep; but as far as it could be ascertained, they had absconded and could not be arrested. Their father, on account of illness, could not leave the house, and being anxious to settle the case, he sent for deceased, who at once obeyed the summons, and proceeded to the blacksmith’s house. He left there early in the evening for his home, but was not seen again till his body was found in the river as already described. Close to the place was a piece of timber placed across the river which might have been intended for a footbridge; but as it was round, it would be almost impossible for anyone to walk over it. In the absence of any conclusive evidence, the Coroner’s Jury returned an open verdict of “Found dead.” The mystery has never been cleared up.

On , the Carmarthenshire Assizes were opened; but as Christmas Day intervened, business was not proceeded with till . On Justice Cresswell Cresswell arrived. The Solicitor-General, Sir Frederick Pollock, appeared for the Crown, and as he was sent down specially to conduct the prosecution, the rioters were much afraid that heavy sentences would be meted out to them. Sir Frederick, however, instead of being severe, as was anticipated, appeared to be most kind and anxious to establish a reconciliation with the country. Owing to the number of prisoners for trial, Special Sessions to try the Rebecca Rioters were appointed for ; but as some of the cases were of considerable importance, they were not all disposed of until before Justice Maule.

“Shoni’ Scubor Fawr” and “Dai y Cantwr” (two notorious leaders of the rioters) were tried and found guilty at these assizes.

Dai y Cantwr was a man of considerable ability, and owing to educational advantages was a good bard. He composed many ballads, and while in gaol under sentence, wrote “A Lament” of which the following is a copy of the first verse:

Drych i fyd wyf i fod,

Collais glod allaswn gael,

Tost yw’r nod dyrnod wael

I’w gafael ddaeth a mi.

Yn fy ie’nctyd drygfyd ddaeth;

Yn lie rhyddid, caethfyd maith,

’Chwanegwyd er fy ngofid.

Alltud wyf ar ddechreu’m taith,

Ca’m danfon o fy ngwlad;

Ty fy Nhad er codiad tirion,

I blith y duon gor

Dros y mor o’m goror gron;

O! ’r fath ddryghin i mi ddaeth,

Alltud hir gyr hyn fi’n gaeth

Dros ugain o flynyddoedd;

Tost yw’r modd cystudd maith.

When Dai’s imprisonment came to an end, he came over to this country, but he only stayed one night at his birthplace, returning to Australia, where he died.

When the Rebecca disturbances started they were confined to a narrow circle, and the newspaper accounts were very meagre in quantity, and very contemptible in tone. It is interesting to notice the development in the attitude of the newspapers as Rebeccaism gained ground. The riots were of such a nature as could not be ignored; they were serious in their results, and they were based on the deep convictions of the perpetrators who thoroughly believed in their cause.

The flame of revolt soon spread abroad, and the circle of action became larger. We find accounts of several disturbances in North Wales which are recorded in the history, and the following account, taken from the Bristol Mercury, shows that Rebeccaism was not confined to Wales alone.

In consequence of an alteration in the line of road leading from Wells through Wedmore to the railway station at Highbridge, several toll-gates have been erected, which appear to have given umbrage to the inhabitants of the localities. In the course of , nightly parties have assembled in great numbers with faces blackened, etc.; and whilst some watched the approaches, others proceeded to demolish the gates with the toll-houses attached: in this manner one in the parish of Mark, and another at Wedmore, have been destroyed.

On , a toll-gate erected a few years since on a new piece of road, between Cheddar and Wedmore, was in a like manner entirely destroyed; and on another in the same neighbourhood shared a similar fate.

Seven individuals implicated in these outrages were committed to prison. It does not appear that any other description of property was at all injured.

With a little training Rebecca would have had a valuable ally in an elephant, which, with his keeper, left Aylesbury on foot for Amersham. When they arrived at the toll-gate of Missenden, the toll-collector closed the gate against Jumbo, as his keeper refused to pay more for him than he would for a horse. The keeper went forward alone, but he had not gone far, when, to the toll-collector’s surprise, the animal quietly took the gate off its hinges, laid it flat on the road, and followed his keeper!

The Welsh grievances had by midsummer of become famous, and aroused the curiosity, the interest, and the sympathy of many people in England. We find one Dr. Bowring in his address to the electors of Bolton, issued in , promising to take up the subject of the Welsh Grievances in Parliament.

At the Royal Amphitheatre, Liverpool, a play called Rebecca and her Daughters was enacted on .

Turning our attention to the riots themselves, we notice that towards the end of the year , they had become most serious, conflicts with the soldiery being of nightly occurrence, and many being taken prisoners. Several were tried before the Special Commission and found guilty, and some of the leaders were sent to penal servitude across the seas.

The question forces itself upon us “Did any material good come out of all this upheaval?” Much misery and tribulation were caused to a large section of the community. Not only were the toll-collectors going in fear of their lives, anxiously waiting their turn, their visitation from the dread Rebecca, but many of the peace-loving inhabitants of the scattered villages went in fear of the rioters, for one and all were commanded to follow the leader, and heavy was the hand that dealt the punishment to those who neglected or refused to answer the call to follow the “Queen” of the rebels.

Yet looking back upon that distant time, now nearly a century gone, we see that most of their grievances have been righted. The Government very wisely appointed a Commission on , to inquire into the condition of things in the Principality, and after a very careful inquiry, and the examination of many witnesses, their report was completed, in which they pointed out the many grievances, making suggestions as to their removal or amelioration.

These were subsequently embodied in the Act of Parliament9 7th and 8th Vict. cap: ⅹⅽⅼ, an Act to consolidate and amend the laws relating to Turnpike Trusts in South Wales, which became law on .

Certain it is that the riots hastened the removal of these grievances. Perhaps they would have disappeared with the progress of the people in education and social advancement, but the riots undoubtedly helped to focus the opinion of the country, and to arrest the attention of the Government to the wrongs and the sufferings of the peasantry of Wales.

“Rebecca” and her children disappeared from the scene as if for ever; but a few old men survived, and a new grievance having sprung up very much after their own hearts, young recruits were not wanting when the enforcement of the law for the protection of salmon by the Board of Conservators made their autumn and winter sport of salmon-spearing a grave offence.10

This gives us an insight into the later Rebeccaism, which made its appearance on the banks of the Wye in .

The common sport of the people had been stopped, and they resented it. They looked upon the rivers and pools as their own peculiar property, and great was their indignation at what they regarded as an interference with their ancient rights and customs.

The people came out nightly to see “Rebecca lighting the water.” Tall, well-set men dressed to the waist in white, with bonnets or handkerchiefs over their heads and their faces disguised, would enter the river. Some carried torches and others spears, all spreading out across the river. The salmon, poor and emaciated, were disturbed by the noise and the light, and, scared, they were helpless while the spearman transfixed them with his weapon. The first one speared would be tossed up on high, and a great shout of triumph, taken up by the watchers on shore, rent the air.

These disturbances took place regularly for many years, getting more serious as the time passed by. The Duke of Beauport had become Chairman of the Board, and set himself the task of putting down this wanton destruction of fish. During twelve riots took place in Radnorshire alone, and the authorities increased the police force by twenty men. This secret organisation of the “later Rebecca” extended over about 150,000 acres, Radnorshire embracing two-thirds and Breconshire the remaining third.

The authorities in this disturbance committed the same grave mistake as they did in the Rebecca Riots, in not realising that the people, rightly or wrongly, believed they had a genuine grievance. The “later Rebeccaite,” as Mr. Green Price puts it, said to himself, “I used to be able to get a fish (salmon) when I liked, could catch him with rod and line, or spear, from the common adjoining the river for miles. Now I am not allowed to look at a salmon, to use a spear is unlawful. My old fishing-ground the commons — has been taken away from me by the Inclosure Acts and has gone to the large landowners.”

We have set forth some of his grievances. Time has shown him that there was cruelty in his action towards the fish, and time also has made him resigned to the action of the great landowner confiscating his land the common — which the peasant rightly regarded as his heritage.

Earlier in the Introduction the question was asked, “Who was Rebecca?” We can now ask, “What was Rebeccaism?”

Rebeccaism was the spirit of revolt, which filled the whole nature of the peasant against the tyranny of the Government, the oppression of the masses by the classes, the fostering of the individual rights at the expense of the community at large. Rebeccaism was the embodiment of the peasants’ anger and righteous indignation at the trampling under foot of his rights and his feelings. Rebeccaism was the spirit of a nation asserting itself against the wrongdoings and evil actions of the few.

Is Rebeccaism dead? Nay, the name may be a forgotten one, but the spirit ever liveth. It is the spirit of democracy crying out against tyranny. To-day it can be heard demanding social reform quite as vehemently, quite as strongly, as did the Rebecca of old demand from the Government of that day, a recognition of its rights and a just treatment of its grievances.

Gwladys Tobit Evans

Trewylan,

- Justin McCarthy’s Short History of Our Own Times, p. 18.

- James Mason in Leisure Hour, .

- “And they blessed Rebekah, and said unto her, Thou art our sister, be thou the mother of thousands of millions, and let thy seed possess the gates of those which hate them.”

- Trial was the name of the house in which he lived,

- The Red Dragon, Vol. ⅺ.

- See Yr Haul, . The Welshman for the same date states the deeds were found.

- Seven Gomer, .

- The chain is now in the possession of Mr. O. Beynon Evans, Cardigan.

- See Appendix A.

- “Rebeccaism,” by R. D. Green Price, an article in Nineteenth Century, .

Chapter Ⅰ

Events leading up to

One night about the middle of , a mob set fire to, and destroyed, nearly the whole of the toll-house at a place called Efailwen, near Llandyssilio, in the county of Pembroke. A short time after, handbills appeared on many public doors, stating that a meeting would be held at a certain place (fixing the day), near Llandyssilio aforesaid, to take into consideration the propriety of a toll-gate, etc., at Efailwen.

Information of the meeting having been given to the magistrates of the neighbourhood, with a statement that it was expected that the riotous mob would proceed from the same meeting to Efailwen, to destroy the toll-gate and toll-house there, several special constables were sworn in and sent to Efailwen. About 10.30 p.m. of the day mentioned, a mob of about four hundred men, some dressed in women’s clothes, and others with faces blackened, marched to the toll-gate, huzzaing for Free Laws and toll-gates free to coal pits and lime kilns; and after driving the constables from their stations, and pursuing them to the fields adjoining, they returned to the gate, and demolished it and the house. In the course of three hours the house was taken down to within three feet of the ground, the gate shattered to pieces with large sledge hammers, and the posts of the gate sawn off and carried away.

On , a third riotous mob armed with guns, etc., marched to a toll-gate near St. Clears, Carmarthenshire, and, after firing off several guns, destroyed the gate; and in a short time there was scarcely a vestige of either gate or toll-house to be seen.

In consequence of these acts of violence, a detachment of Her Majesty’s 14th Regiment arrived on at Carmarthen, and thence proceeded to Narberth.

The Summer Assizes opened on , before the Hon. Sir John Gurney Knight, one of the Barons of Exchequer, but there was not a single prisoner for trial either in the Borough or County.

After the destruction of the Efailwen toll-house and gate, a chain was put up, guarded by a body of constables. On , a mob collected in open day, pursuant to public notice on , and a certain number of men dressed in women’s clothes, and headed by a distinguished one under the title of “’Becca,” proceeded towards the spot with blackened faces, and bludgeons on their shoulders. At their savage and frightful appearance, the constables took to their heels, and all effected their escape, with the exception of one who was lame. He, having run about five hundred yards, was overtaken and immediately knocked down and much abused. The rioters were informed of the day and hour of meeting, by placards, of which the following is a specimen, posted and handed about Dissenting Chapels on the Lord’s Day.

Men of Efelwen

Llanboidy!!!—Let not your feelings, however excited, lead you to blame or injure the native magistrates of your native Country. They have commiserated those feelings. They sympathise with you!!!

Boldly represent to your Sovereign the unparalleled fact that two Sassenachs with scarcely a qualification, and one from a neighbouring isle, have strained your laws to an imprudent tension!

A rara Avis in terris, nigroque simillima Cygno!

An Apostate!! A Fortune Ganger!!!

These support a little Bull in the matter—

Pricilla Top, .

’Becca.

was ushered in by riots at Newport, the leaders being John Frost, Zephaniah Williams and —— Jones. They all received sentence of death on .

On , a large mob assembled at St. Clears, and destroyed the toll-gates on the main Trust at Llanfihangel and Tawe Bridge. The same night also a toll-gate on the Whitland Trust, near the Commercial Inn, was destroyed. The leaders of the mob were disfigured, having painted their faces various colours, wearing horsehair beards and women’s clothes. The depredators had patrols in every direction, to stop all travellers from proceeding on their journey during the time the demolition was going on. The doors of all the houses in the neighbourhood were locked, and the inhabitants confined within, not daring to exhibit a light in their windows; they had had a gentle intimation from the mob to that effect, and from fear of being ill-treated they obeyed the command.

During the day Narberth Fair was held. The mob stopped all the drovers coming from the direction of Carmarthen, and levied a contribution from them, stating that they had destroyed all the toll-gates, and consequently they (the drovers) had no toll to pay.

Chapter Ⅱ

Mob Law Commences

The New Year, , opened with the destruction of Trefechan, Pentre and Maeswholan gates. Rebecca’s power increased daily, and it was an open boast that she had the support of five hundred men faithful and true, in the neighbourhood of Haverfordwest. These men actually believed that they had the right to break the law.

In , a detachment of the Castle Martin Yeomanry, under the command of Captain Bryant and Lieutenant Leach, received orders to proceed from Pembroke to St. Clears, in consequence of the unsettled state of the neighbourhood, caused by Rebecca and her children. They were served with pistols, carbines, and bayonets, each man carrying twenty rounds of ball cartridge. On , the Castle Martin troop of Yeomanry under the command of Captain Henry Leach was also despatched from Pembroke to St. Clears to relieve the one doing duty there in consequence of the disturbances.

Early in the morning of , the renowned lady Rebecca, together with some of her daughters, all disfigured and disguised in women’s clothes, their faces covered, and well mounted, made their appearance at Ganneg Gate, near Kidwelly, which they entirely demolished. The fragments of the gate-posts and toll-board were afterwards found in a river, a short distance from the place. Some of the people living near, asserted that about the time the gate was destroyed, they heard the trampling of a great many horses, but on their approach could not identify any of the parties. This proved that they must have come from a long distance.

The adjourned Quarter Sessions for the county were held in the County Hall, Carmarthen, on . A discussion took place there, with regard to the police pensioners and cavalry at St. Clears, and an order was made to publish in the local papers the Address of the representatives of the parish of St. Clears, etc., to those persons who committed the outrages. It is as follows:

Fellow Countrymen,

This address is signed by us who have met this day at the Blue Boar Inn, St. Clears, as representatives of the several parishes of St. Clears, Llanginning, Llandyssilio, Llanboidy, Llangain, Llanfallteg, Llanddewi, Llanfyrnach, Kilmaenllwyd, Llangludwen, Llanfihangel-Abercowin, Eglwyscummin, Trelech, Laugharne, etc., etc., for the purpose of entreating you to co-operate with us in preventing the future destruction of Llanfihangel, Pwlltrap, and other turnpike-gates, and when we tell you that the late riotous assemblies have already cost the ratepayers of the County of Carmarthen little less that £7,000, we are sure you will render us every assistance to preserve the peace of the county, and to bring the guilty to justice.

Our neighbourhood has hitherto been both peaceable and quiet, and the great many religious privileges which we enjoy ought to be a protection against the unlawful assemblies which have now unfortunately brought upon us both shame and disgrace, and our only hope for redress must be this public appeal to the good sense and Christian feelings of our fellow-countrymen, and while we remind them that the penalty for destroying turnpike-gates is no less than transportation for seven years, we trust that the remembrance of the wickedness and evil consequences of such illegal acts will outweigh any other considerations.

The keeping of the police and military at St. Clears must take money out of our pockets, which none of us can afford or wish to pay, but, as long as the laws are disobeyed, they cannot be removed. Let all the county be united in promoting peace and goodwill, and we shall again be a happy people.

We are perfectly satisfied that the magistrates and higher authorities sympathise with the country, and we are sure that they will, as far as in their power, afford us every relief; but at the same time we are convinced that they will, as in duty bound, support and enforce the laws of the country. Dated at St. Clears this . [Signed by sixty-nine persons.]

A meeting of the magistrates was held at the Blue Boar Inn, St. Clears, on , to take into consideration the best mode of restoring peace in that district. About fifty respectable farmers came forward, and were sworn in as special constables. The Yeomanry left the same evening for head-quarters Pembroke.

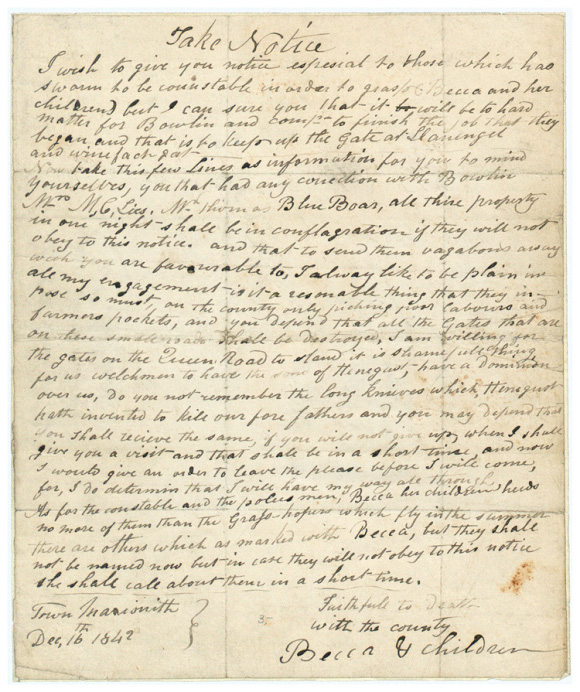

The following is a verbatim et literatim copy of a letter1 received by Mr. Bullin, the contractor for certain gates Carmarthenshire:—

Take notice I wish to give you notice espesial to those which has sworm to be constabls in order to grasp Becka and her childrens but i can sure you that it will be hard mater for Bowlins and company to finish the job that they began and that is to kep up the gate at Llanfihangel and weinfach gate. Now take this few lines information for you to mind yourselves, you that had any conection with Bowling Mrs. M,c, Les Mr. Thomas Blue boar all their property in one night shall be conflaration if they will not obey to this notice, and that to send them vagabons away which you are favourable to i always like to be plain in all my engagment is it a reasonable thing that they impose so must on the county only pickin poor labrers and farmers pocets, and you depend that all the gates that are on these small roads shall be destroyed, I am willing for the gates on the Queens Roads to stand it is shamful thing for us Welshmen to have the sons of Hengust have a Dominion over us, do you not remember the long knives, which Hengust hath invented to kill our forefathers and you may depend that you shall receive the same if you will not give up when I shall give you a vicit, and that shall be in a short time and now I would give you an advice to leave the place before i will come for i do determine that i will have my way all throught. As for the constables and the poleesmen Becka and her childrens heeds not more of them than the grashoppers flyin in the sumer. There are others which are marked with Becca, but they shall not be named now, but in cace they will not obey to this notice she shall call about them in a short time faithful to Death, with the county — Rebecka and childrens

There were also sent to Mr. Bullin two woodcuts, one of a man without a head, with a written heading “Receipt for the interest I took in the Matter,” and the other, of several persons marching with clubs, pickaxes, etc., with the heading “Going to visit St. Clears Gate, when we think proper — Dóroma Buchan.”

The inscriptions over the woodcuts were in a better handwriting than the letter, which was written on ruled paper torn out of a memorandum book. It was examined by some of the Carmarthenshire magistrates, and the signature and handwriting were found to correspond with threatening letters sent to other persons. As intimated in the letter, Rebecca did not object to the gates on the Queen’s high road, but destroyed those on roads repaired by the various parishes, upon which the Turnpike Trustees erected gates and demanded tolls. This rendered Rebecca not unpopular amongst some farmers and others, many of whom paid the fine, rather than be sworn in as special constables.

The following night, , a mob of forty or fifty persons destroyed two turnpike-gates at Trefechan, one leading to Lampeter, the other to Tavernspite, both in the county of Pembroke, and at the same time destroyed the turnpike-gate house, which was levelled, the gate-keeper having left it a little time previously for the night. There can be no doubt that the mob came from the English part of Pembrokeshire, as a person who had hidden himself in a garden just by the gate saw them come up the Lampeter road, watched their proceedings, and heard them converse in the English language only. Three of four of them appeared in disguise. The others seemed to be clad in their usual dress. These gates belonged to the Whitland Trust, and were repaired by the parishes, which seems to have been the principal grievance.

A number of persons tumultuously assembled at dawn on , and pulled down the toll-bar erected near the village of Llandarrog; not content with that, they actually set fire to the materials and totally consumed them, together with the toll-box belonging to the said bar. A reward of £50 was offered for the detection of the offenders. , a person had applied to the toll-keeper and offered him five shillings for the passage of a wedding party which was to go that way on the lyth. The toll-collector had refused to accept anything under ten shillings. However, the whole was destroyed as before mentioned, and the wedding party passed free.

Thomas Howells of Llwyndryssi, farmer, and David Howell, miller of Llangain, were examined before the magistrates of St. Clears on , upon a charge of having, in company with others, destroyed Trevaughan Gate on the Whitland Trust. Lewis Griffiths of Penty-park Mill, Pembrokeshire was the principal witness against them. He swore that he saw the prisoners in the act of demolishing the toll-house and gate at Trevaughan. On their committal, his departure was hissed and hooted by a crowd of women and girls who had assembled to witness it.

On , two of Rebecca’s daughters were taken prisoners and imprisoned at Haverfordwest. They appeared to be respectable men.

About this time the following verses were composed, and their popularity can easily be imagined.

Rebecca and Her Daughters

Where is Rebecca? — that daughter of my story!

Where is her dwelling? Oh where is her haunt?

Her name and her exploits will be completed in history

With famed Amazonians or great “John of Gaunt.”

Dwells she mid mountains, almost inaccessible,

Hid in some cavern or grotto secure,

Does she inhabit — this miscreant Jezebel,

Halls of the rich, or the cots of the poor?With exquisite necklace of hemp we’d bedeck her

Could we but capture the dreadful Rebecca!

Who is Rebecca? She seems hydra-headed

Or Angus-like — more than two eyes at command,

The mother of hundreds — the great unknown dreaded

By peace-loving subjects in Cambria’s land.

Unknown her sex too — they may be discovered

To all our bewildered astonishments soon

To be, Mother Hubbard, who lived in a cupboard,

Great Joan of Arc’s ghost or the man in the moon.

’T would puzzle the brains of a Johnson or Seeker

To make out thy epicene nature — Rebecca!Who are thy daughters? in parties we meet them,

Which proves them of ages quite fit to come out,

Some Balls it appears were preparing to greet them,

Which soon would have ended of course in a rout.

They are not musicians, though capital dancers,

So puzzled they seem to encounter each bar;

But — Shade of Terpsichore! call for the lancers,

How fastly they’ll step out with matchless éclat;

The wonderful prophet who flourished in Mecca

No heaven could boast like thy daughters, Rebecca!What are your politics? Some people say for you —

Travelling System you always will aid,

And ’twould appear the far happiest day for you,

Throwing wide open the road to free trade,

You cannot with Whigs take up any position,

If what I assert here is known as a fact;

That you give decided and stern opposition

To all that may hinge on the new Postage Act.

The State is in danger, and nothing can check her

From ruin with politics like yours — Rebecca.Farewell, Rebecca! cease mischievous planning,

Whoever you might be — Maid, Spirit or Man;

Lest haply your days should be ended by hanging,

And sure you’re averse to that sad New Gate plan.

Oh no! to the drop you may never be carted,

No end so untimely e’er happen to you:

But change, and be honest, and when you’re departed

May have from the Sexton, the Toll that is due.

My muse is at fault — I may pinch and may peck her

But all to no purpose — Good-bye then, Rebecca!.

- Cambrian, .

Chapter Ⅲ

The Evil Spreads

Robeston Wathen Gate, near Narberth, and Canasten Bridge Gate were utterly demolished on by a riotous mob of Rebeccaites. They assembled in considerable numbers on horseback in the neighbourhood of Robeston Wathen, and immediately proceeded to demolish the toll-gate at that place belonging to the Whitland Trust. The old woman who resided in the toll-house, hearing a noise, went to the door and inquired what was the matter. One of the rioters answered, “You had better hold your tongue and stay within doors; if you come out we will murder you.” Having levelled that gate with the ground, they proceeded to the Redstone Gate, also belonging to the Whitland Trust, which shared the same fate as the other. The gang then rode off at a rapid pace.

The rioters threatened that should any harm happen to Howells of Llwyndryssi, and David Howells, then at Haverfordwest Gaol for trial on suspicion of being concerned in these riots, that they would show no mercy to anyone, but would harry the whole country.

A night or two after this, Rebecca and her daughters paid another visit to Narberth, and totally destroyed the two eastern gates at the entrance to the Whitland road. They reached there about 1 a.m., in number from eighty to a hundred, headed by three on horseback in female attire, their horses being covered with white sheets. After the work of destruction had been effectually completed, which occupied them about a quarter of an hour, they marched through part of the town, and then separated, taking different roads and giving off several shots. The night previous they had called at some farm-houses in the neighbourhood, demanding money, drink, etc., which, through fear, in most instances were given to them.

Some of Rebecca’s disciples on assembled at Kidwelly Gate, leading to Carreg mountain, and completely demolished the toll-house. The gate and posts had been destroyed a month or six weeks previously.

six or seven evil-minded persons demolished the Penclawdd Gate in the parish of Conwil, on the turnpike road between the latter village and Newcastle Emlyn. Not content with this outrage, they broke into the toll-house, disguised and armed with guns, threatened the tax-collector and his wife with instant death if they persisted in hurrying out in a state of nudity into the road, and they then proceeded to destroy the house, in which they partially succeeded.

The Spring Assizes opened before Sir W. H. Maule on . Thomas Howells and David Howells were tried at Haverfordwest for being concerned in ’Becca’s disturbances, and both were acquitted.

The Narberth Gate, Plaindealings, and Cott’s Lane Gates were entirely destroyed by a lawless mob on . In a very short space of time the work of demolition was complete, and the perpetrators returned through the town, firing volleys in token of their triumph.

, a second daring and destructive attack was made on Prendergast Toll-gate, near Haverfordwest, by a party of about twenty-four men, some of whom were dressed in smock frocks; they came down in a body from the Fishguard road headed by a tall man in a white mackintosh. The first movement on arriving at the toll-gate was to appoint some of the mob as guards at the doors of the neighbouring cottages to prevent anybody from coming out to interrupt their operations. They advised Phillips, the toll-taker, “to keep in the house if he was not quite tired of his life, because they intended no harm to him.” The captain then gave orders to commence the assault, and the mob went to work in good earnest; they did not desist till they had reduced the gateposts and signboard to splinters. They then told Phillips that they had fixed on that night for doing the job because it was bright moonlight, which would prevent them injuring their hatchets! On leaving they gave a hearty cheer, and carried away with them a portion of one of the posts in token of their triumph.

, Rebecca and a number of her offspring proceeded to Bwlchtrap, near St. Clears, and, after arriving at the gate, the following colloquy took place between the old lady and her youthful progeny. Rebecca, leaning on her staff, hobbled up to the gate, and seemed greatly surprised that her progress along the road should be interrupted.

“Children,” said she, feeling the gate with her staff, “there is something put up here. I cannot go on.”

Daughters. What is it, mother? Nothing should stop your way.

Rebecca. I do not know, children. I am old, and cannot see well.

Daughters. Shall we come on, mother, and move it out of the way?

Rebecca. Stop; let me see (feeling the gate with her staff). It seems like a great gate put across the road to stop your old mother.

Daughters. We will break it, mother. Nothing shall hinder you on your journey.

Rebecca. No; let us see, perhaps it will open (feeling the lock). No, children. It is bolted and locked, and I cannot go on. What is to be done?

Daughters. It must be taken down, mother, because you and your children must pass.

Rebecca. Off with it, then, my dear children. It has no business here.

With that all the “children” set to, and in less than ten minutes there was not a vestige of the gate or posts remaining. This done, the whole party immediately disappeared. The London police were at the Blue Boar Inn at the time, but they had not the least intimation of what was going forward until their services could be of no avail.

The above amiable lady and her dutiful daughters were on at their usual nocturnal malpractices at Bwlchydomen, near Newcastle Emlyn. On this occasion they numbered about fifty, all armed with guns and pistols, besides the tools of destruction they carried with them. In less than a quarter of an hour both the gate and the posts were completely demolished, and a part of the toll-house met with a similar fate. After this the rumour rapidly spread that Rebecca intended very shortly to visit Velindre and Newcastle Emlyn Gates, and that it was her intention to destroy them also.

Rebecca and her children assembled on the night of at Bwlchclawdd Gate, about three miles from Conwil. They completely destroyed the turnpike-gate and toll-house. In consequence of this raid, notices were issued to recover the damage sustained by this destruction from the hundred of Elfed.

Trevaughan Gate was once more entirely demolished on , the toll-house being levelled with the ground, and the stones of the building carried away and thrown into the river at some distance from the gate.

The Llanvihangel Gate was again destroyed by Rebecca about . She had four sentinels with loaded guns placed on the bridge to prevent the police from interfering with her followers, and no doubt had they made their appearance they would have been fired upon. When the gate was destroyed, the Rebeccaites fired off their guns, which alarmed the police, who immediately went in pursuit; but it proved fruitless, for by the time they got to the gate, ’Becca and her children had vanished. Why they should again destroy this gate is a mystery, for no tolls had been demanded there after the previous demolition.

A plantation belonging to Timothy Powell, Esq., of Pencoed (a magistrate active against Rebecca), was fired on , and four acres were burnt. The remaining eighteen acres were saved.

Rebecca, with her respectable family, paid a visit on to the gates in the Llandyssul district. They commenced their work of destruction at Pontweli Gate, then at another gate close by called Troedrhiw-gribyn, the gate and posts of which were entirely destroyed. The band consisted of twenty or thirty, the greater number of whom were dressed in women’s clothes; and what appears very extraordinary is that a great number of the inhabitants of Llandyssul were present, looking on at the work of demolition. ’Becca publicly stated there and then that they had several more gates to pull down, and especially named Newcastle Emlyn.

A week later some daring and intrepid depredators of turnpike-gates paid a visit to the quiet little town of Fishguard, and removed the gates and posts in the western part of the town to a neighbouring field. They were completely smashed into pieces. It is but just to say that the Fishguard Turnpike Trust had not repaired any of the roads in the parishes of Fishguard, Dinas, or Newport, through which the Trust led, but all the business of keeping the roads in repair fell entirely on the parishes. The Act of Parliament for the taking of tolls at those gates had expired several years, so that the levying of tolls at the Fishguard turnpike-gates was a very great imposition, and loudly called for redress.

A meeting of the inhabitants of the hundred of Derllys was held at St. Clears on . Resolutions were passed praying that a rural police be not established, the expense of which would fall heavily on the farmers and ratepayers of that hundred.

The quiet little town of Lampeter was visited about the end of May. The turnpike-gate called the Pound Bar was taken off its hinges and thrown over the bridge into the Teify. Contrary to Rebecca’s usual method, very little noise was made on this occasion sure proof that only a small band was engaged on the work.

Chapter Ⅳ

The Rioters Grow Bolder

The inhabitants of Carmarthen had often read of Rebecca and her doings in different parts of the country, but had not the opportunity of witnessing the depredations committed by this celebrated Welsh outlaw before the end of , when she and her sister Charlotte, together with about three hundred of her children, paid a visit to Water Street Gate in that town.

They commenced their work of destruction about one o’clock in the morning, and completed the whole in about fifteen or twenty minutes. About ten minutes before Rebecca’s arrival the gate-keeper had been out taking toll for a cart, and he had only just returned and laid himself down in his clothes on the bed, when he heard a thundering noise and ran towards the door; but before he could reach it, it was struck in against him, and Rebecca and her sister came into the passage. He saw it would be useless to make any resistance, and said, in order to save himself from being ill-treated, “Oh! ’Becca is here. Go on with your work, you are quite welcome!” Rebecca desired him not to be alarmed, as they would do no injury whatever to him. The gate-keeper begged of them not to destroy the furniture, as it was his own; and his wife and child were in bed, but they might do as they liked with the gate and toll-house. Rebecca went to the door, and ordered her daughters not to touch anything but the gate and the roof of the toll-house, and not to break the ceiling for fear the rain would harm the woman and child in bed. In their hurry, however, to unroof the house, one of them slipped between the rafters, and his foot got through the ceiling. Rebecca expressed her sorrow at the accident, as it might cause inconvenience to the gate-keeper. She and her sister then told the gate-keeper that they had visited Water Street Gate, in consequence of the information laid by David Joshua, keeper of the Glangwili Gate, against a person the previous week; and they would destroy the Water House and Glangwili Gate before , and would take off David Joshua’s head with them.

During the whole of that time the work of destruction was carried on in the most furious manner, with large hatchets and cross-saws; a number of men had taken a ladder, and ascended the roof of the house, which was completely stripped in a very short time.