How you can resist funding the government → getting under the income tax line → it’s not very difficult

- What sort of tax resister are you, anyway?

- There are many ways to resist taxes, and many reasons to. Tax resisters use different strategies, have different objectives, and have different reasons why we take our stands. I resist my federal income tax by keeping my income low and using legitimate deductions and credits that reduce the tax to zero, and I resist federal excise and self-employment taxes in other ways. I do these things to reduce my complicity in the actions of the government.

- Is what you’re doing legal?

- All of us illegally evade taxes to some extent — not because everybody is trying to get away with something, but because most of us are unaware of just how much is taxable and how much fuss we’re technically obligated to comply with. On the other hand, even dedicated tax resisters find it difficult to avoid paying any taxes. There’s a big gray area in the middle between absolute compliance and absolute evasion. When I started resisting, my strategy was to do so above-board and legally, so although I was in the gray area along with everyone else, I actually did things more by-the-book than before. It’s been part of my experiment to show that even if you want to follow the rules you don’t have to pay federal income tax if it would compromise your values. In , I started resisting federal self-employment tax as well — by simply not paying it, which isn’t legal. So I currently use a combination of legal and non-legal methods to resist paying taxes.

- What do you mean “everybody evades taxes”? I pay all my taxes!

- Do you pay “use tax” on things you bought out of state and therefore didn’t pay sales tax on at home (if you’re in a sales tax state, like most of us)? I didn’t even know this tax existed until I started tax resistance and did some research. This is one example of a tax that people are technically obligated to document, report, and pay, but that in practice people evade out of ignorance or frustration at the paperwork.

- Have you considered earning money in the underground economy and never declaring it to the IRS?

- I’ve given this some thought. I think if you can get away with earning undeclared income, it makes sense to do so. On the other hand, you can resist taxes even if you want to do everything above-board and by-the-book. If the right opportunity in the underground economy comes along, I might take it. I may decide not to discuss it on this blog, though, because that could be used against me by the powers-that-be. As of the time I’m writing this, I have not earned any significant amount of undeclared income and I still pursue federal income tax resistance through legal means. This might change.

- Don’t you know that you don’t have to pay income tax because wages aren’t really income and the sixteenth amendment wasn’t legally ratified by Ohio and anyway it doesn’t apply to people living in states but only those who live on federal land, and all you have to do is declare yourself a sovereign citizen and buy this book?

- I often get advice like this, but I see a fatal flaw: The IRS and the courts are the ones who get to decide what the rules of the game are and when they can seize your property or throw you in prison, and they don’t read the same book you’re reading. They’ve decided that arguments like these won’t fly. However, even completely silly tax arguments can “work” just because it’s so much trouble for the IRS to unravel them. Unless there’s plenty of money involved or it’s a high-profile case, it isn’t worth their time. So although these legal theories have about as much to recommend them as Nigerian Scam emails and pyramid schemes, I’m glad some people have taken this on as a hobby. I think I’ll pass, though.

- Do you think you’re going to enjoy a life of abject poverty?

- Who said anything about abject poverty? I just want to live under the tax line. I can earn $50,000 a year, and then, by doing things like putting some in tax-deferred retirement accounts and some in a Health Savings Account, keep about $23,750 to live on. Thanks to perfectly legal, above-board, IRS-approved deductions and exemptions, I won’t have to pay any income tax on any of that. In , the median per capita income in the United States was $37,522. Other stats I’ve seen suggest that something like 91–92% of the world’s population earns less in a year than I get to spend after putting away 35–40% of my income for retirement. About 500 million people living on the planet with me right now are trying to get by on less than 2% of that. I’m filthy rich! And I’m not paying taxes! It’s the American Dream! I won’t have to sell my body for top ramen money any time soon. I’ll be fine.

- Wait a minute: You can pull in $50K without paying income tax? Legally? How does that work?

- You can read my (free, on-line) how-to guide for some details. It’s a little-known fact that paying no federal income tax is very common in the United States. According to The Tax Policy Center, about 40% of households in the U.S. were expected to pay no federal income tax at all for tax year .

- But you won’t really have $50K to spend — a lot of it is tied up in this and that, right?

- Yes, to some extent. For instance, one way to make $50K income tax free is to put some of it into tax-deferred retirement accounts, some into a Health Savings Account, donate some to charity, and spend some on college tuition. But it’s still your money that you get to spend, and there are worse ways to spend your money. And because you’re not paying taxes, that $50K is a real $50K: forty thousand full dollars, not after-tax dollars. Before I embarked on tax resistance, each dollar I earned was reduced 17½¢ by federal income tax withholding. By eliminating that tax, I gave myself a raise by increasing the value of every dollar I earned and thereby increasing my take-home pay for every hour I worked.

- But not everybody could get those deductions, you know.

- True — different people have different deductions they can take and different financial obligations they must meet. I don’t have a car, or children, or a chronic disease, or a mortgage, or student loan debt. I’ve got more flexibility in my finances that allows me to consider a step like this.

- How did you find out about the deductions and credits you use, and how do you know they’re legit?

- I mostly learned about the credits and deductions that I use by reading IRS documents like Publication 17 — the agency’s how-to guide for individual income tax filers. To delve further into the fine print, I looked to other IRS documents.

- If I want to do tax resistance, do I have to choose between poverty and persecution?

- There are also the paths of prevarication and paperwork! Seriously, though, in the field marked off by those four “P”s there’s a lot of territory. Some tax resisters are persecuted by the government, and some deliberately provoke this sort of confrontation as part of their protest. And some resisters do adopt a voluntary simplicity lifestyle that seems impoverished to some people. But many resisters are neither persecuted nor impoverished. There are many tactics, and many ways to go about using them.

- You may be avoiding federal income tax, but you still owe self employment tax, and pay California sales tax (and maybe the state income tax), various excise taxes, tariffs (indirectly anyway), etc. What about that?

- There’s that gray area again. I wonder what I’d have to do to avoid paying (or owing) any taxes at all. I’d probably have to avoid money altogether, since some is lost to tax just about every time it changes hands. I couldn’t get vaccinated, since there’s an excise tax on vaccines. I couldn’t eat food that had been shipped using taxed fuel. I couldn’t drink booze that hadn’t been home-brewed or bootlegged. I couldn’t leave the country and return legally, since there is a high fee to purchase a passport. I’d have to avoid using any products that were subject to an import tariff — or maybe any products whose manufacturers or sellers made a taxable profit or who paid their employees taxable salaries. Sounds pretty tough. I think I’ll stick with moral impurity for now and put off sainthood for another day. That said, where there’s room for improvement I’m eager for suggestions. I have home-brewed beer to avoid the excise tax on alcohol, and these days I avoid booze entirely. I don’t own a car so I pay little excise tax on gasoline directly. As for the self-employment tax, I decided in to just stop paying it (non-legally). So far that’s worked out fine.

- If you think the government is so bad, why don’t you just leave the country?

- If you are asking whether I’ve considered moving to another country as a way to live on less money, avoid support of the U.S. government, get out from under the thumb of Uncle Sam, spend my suddenly large bank of free time by seeing a bit more of the world, and so forth — I have considered this and am considering it. If what you’re asking is “If you hate the government so much, why don’t you leave its country” then the answer is different: I don’t believe this country belongs to the government. I don’t believe that by opposing the government, I become less invested in the place where I was born, where I grew up, and where I live. In short, I think that it’s the government that’s the problem, and that if push comes to shove it’s the government that should leave the country, not the people.

- Do you just want to “not support” the government, or actually to resist it in some fashion?

- I think many protesters with their signs and chants and their #hashtags are fooling themselves if they think they oppose the government — their actions and their rhetoric don’t take a nickel from the bottom line of their actual support. I think a compelling case for the need to resist the government can be made. Now, finally, I have earned the right to weigh that case. Once I stop supporting the government, I can decide whether to wash my hands of it or whether to go further and actively oppose it.

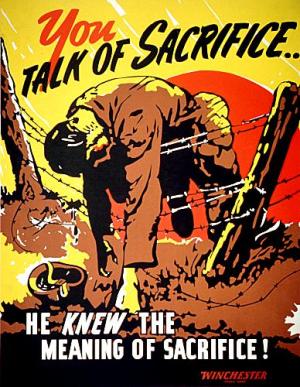

- Don’t you know that many brave people have fought and died so that you would have the right to espouse the tripe that is your opinion?

- I’ll try to hold up my end of the bargain.

- How can you reconcile withholding financial support for our federal government and continuing to benefit from services supplied by that same government?

- I see what you’re getting at, but I think this is a sham argument. Let’s say Al Capone sets up shop in your neighborhood and offers you the standard mob protection racket deal: “We’ll make sure your home doesn’t burn down and your kneecaps don’t get broken if you pay us $50 every week — it’s great insurance.” You grumble but pay, resenting it all the while. Now imagine Al Capone uses some of the money you and your neighbors have been coughing up to add a new wing to the hospital, or to throw a party for returning war veterans, or to buy a truck for the volunteer fire department? Should you stop resenting being shaken-down every week? Should you start being glad you’re being extorted? Should you feel guilty if you can weasel out of paying? How much of your money does Al Capone have to spend on philanthropy before it becomes okay that he’s extorting it from you?

- Taxes are the way everybody chips in to fund things of mutual benefit, like national parks and the social safety net. By refusing to pay taxes aren’t you shirking your duty to help out?

- When I hear this argument, I imagine a favorite charity: maybe Amnesty International, or Habitat for Humanity, or Doctors Without Borders… something like that. What if I learned that my favorite charity spends half of the donations I send to them on a campaign of murder, brutality, and torture? Would I continue to send them checks to support the good things they do with the other half of my money, or would I find another charity to support? Nothing about tax resistance prevents you from contributing your time and money to beneficial projects. It just means you intend to do so in a way that doesn’t also contribute to the harmful projects of the government.

- Speaking of charity, why don’t you just continue to earn as much money as you used to, and then donate enough to charity that your taxable income drops below the tax line?

It’s a common misconception that people can get under the income tax line by donating a sufficient amount to charity. I’ve run the numbers, and it’s not that simple. The first problem is that the deduction for charitable donations is an itemized deduction, so you have to donate enough to get your itemized deductions as high as your standard deduction before you reduce your taxes. (As of there is a $1,000 above-the-line tax deduction for charitable contributions that you can take even if you don’t itemize, so this can help a little bit.) The second problem is that your deduction is typically limited to some percentage of your adjusted gross income. The third problem is that you take your itemized deductions after you calculate your adjusted gross income, so you can’t reduce your AGI that way and therefore can’t use this method to qualify for tax credits that require a low AGI (like the retirement savings tax credit I rely on).

Every once in a while the government loosens some of these restrictions. For instance, in the wake of Hurricane Katrina they allowed people to make tax-deductible hurricane-related donations up to 100% of their AGI. The ceiling on charitable deductions was also removed in the wake of the CoViD-19 epidemic in . These opportunities are difficult to predict, however, and only help with the second of the three problems.

- Is this site going to end up just being some shady excuse to beg money from people?

- No.

- Do you really think you’re going to change the government’s policies this way?

- No, I don’t. Some people resist taxes as a protest directed at people in power or as a tactic to try to force concessions from the government. But the reason I resist is to stop my personal support of the government — to wash my hands of it. I had a selfish desire to live my life according to my principles, and not a grander agenda of regime change or reform. Which isn’t to say that I don’t want change, just that this path wasn’t chosen with that goal in mind. That said, I like to think that by writing about what I’m doing I might encourage other people to try tax resistance. What if 10% of people who are of the opinion that the government is run by a bunch of psychopaths actually withdrew their support? Well, I don’t know what would happen, but I think it would mean more than if they all tweeted about how angry it makes them feel or they decided to vote for some politician or they paraded around in the streets again. Tax resistance is a good exclamation point at the end of my convictions — a way of saying “and not only that, but I mean it!”

- Is there an RSS / XML feed for this site?

- Yes: https://sniggle.net/TPL/rss1.xml is the RSS 1.0 feed and https://sniggle.net/TPL/atom10.xml is the Atom 1.0 feed.

- Why are acronyms and abbreviations, like IRS, underlined in Picket Line RSS feeds?

- I use the HTML element

<abbr>to mark an abbreviation. I usually include the full or spelled-out versions of abbreviations in the “title” attribute of the tag. Some web browsers note the presence of such tags by underlining the enclosed text, and if you hover the mouse pointer over such an underlined abbreviation, a little pop-up window will display the contents of that “title” attribute. You may not find this particularly useful, but people with impaired vision who use audible screen readers to read web pages might appreciate hearing “US” pronounced differently depending on whether it’s a capitalized version of the word “us” or an abbreviation for “United States,” for instance. This may also help search engines and other automated tools to analyze the pages on this site more usefully. - Is there a topic index to this site that I can use to find information on a particular subject?

- Yes, and it’s unique to the blog-world as far as I know: Take a look at the outline page. It’s organized not in alphabetical order, but in clusters of topics that kind of mirror one way the content on this site might be grouped.

- Who is this Ishmael Gradsdovic?

- He’s my imaginary friend. That’s more substantial than a nom de plume but less scary than a psychotic break with reality. He tells some interesting stories, like the one about his baseball-theorizing college friends, or the time his free will disappeared, or his photojournalist stint in the opening days of the Afghanistan War. He has a telepathic, clairvoyant tapeworm who interviewed Mahatma Gandhi, Aristotle, and Epictetus. Sometimes he writes letters to the editor.