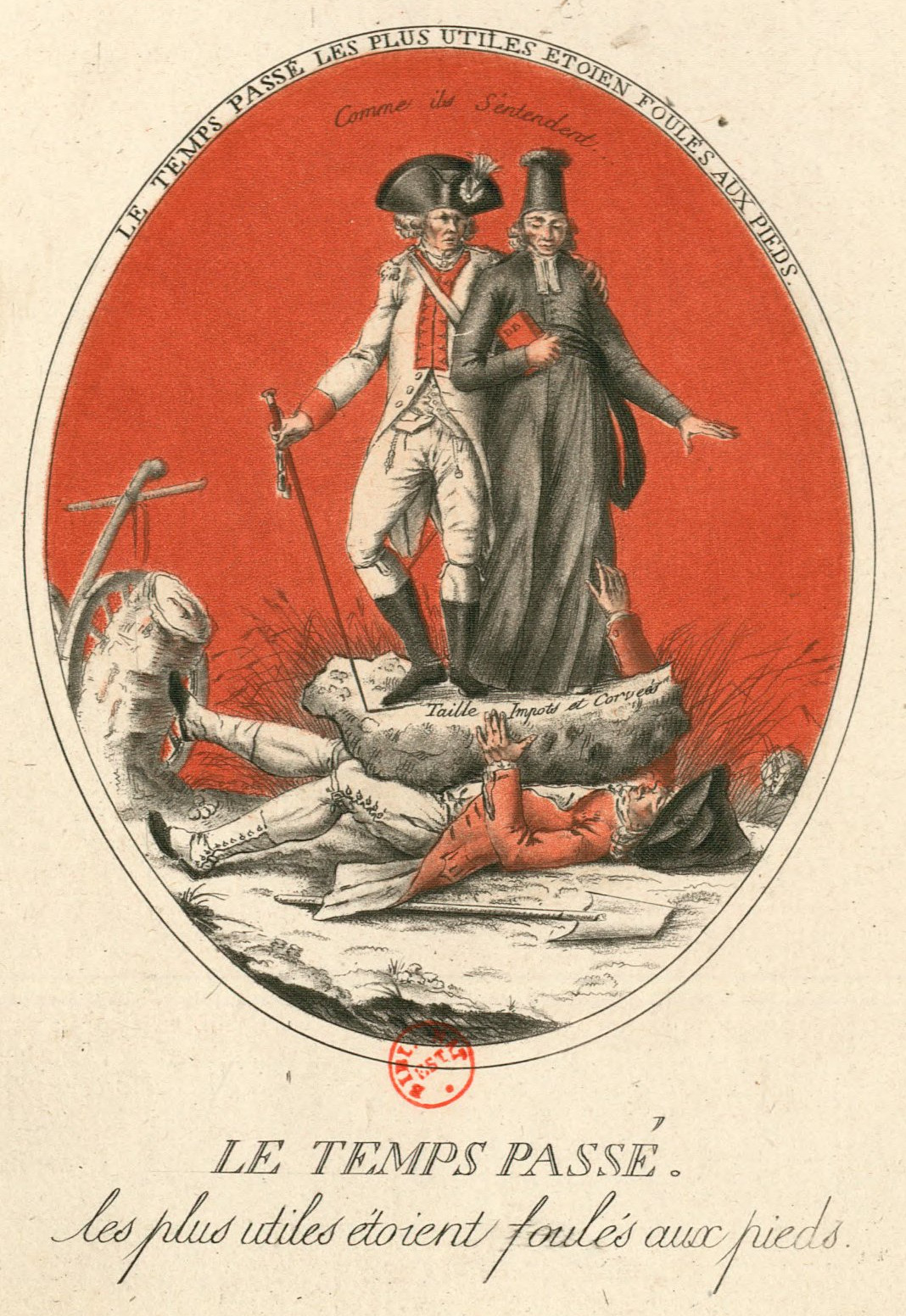

As Hippolyte Taine tells is, the French Revolution was a time of widespread tax resistance against every government that popped up. Though this reads less like tax resistance against or in protest of the government and more like total contempt and disregard for the government and its supposed power to tax.

After , among the populace which attacks the Hôtel-de-Ville and besieges the bakers’ shops of Nantes, “shouts of Vive la Liberté! mingled with those of Vive le Roi! are heard.” A few months later, around Ploërmel, the peasants refuse to pay tithes, alleging that the memorial of their seneschal’s court demands their abolition. In Alsace, after , there is the same refusal “in many places;” many of the communities even maintain that they will pay no more taxes until their deputies to the States-General shall have fixed the precise amount of the public contributions. In Isère it is decided, by proceedings, printed and published, that “personal dues” shall no longer be paid, while the landowners “who are affected by this dare not prosecute in the tribunals.” At Lyons, the people have come to the conclusion “that all levies of taxes are to cease,” and, on , on hearing of the meeting of the three orders, “astonished by the illuminations and signs of public rejoicing,” they believe that the good time has come; “they think of forcing the delivery of meat to them at four sous the pound, and wine at the same rate. The publicans insinuate to them the prospective abolition of octrois, and that, meanwhile, the King, in favour of the re-assembling of the three orders, has granted three days’ freedom from all duties at Paris, and that Lyons ought to enjoy the same privilege.” Upon this the crowd, rushing off to the barriers, to the gates of Sainte-Claire and Perrache, and to the Guillotière bridge, burn or demolish the bureaux, destroy the registers, sack the lodgings of the clerks, carry off the money and pillage the wine on hand in the depôt. In the mean time a rumour has circulated all round through the country that there is free entrance into the town for all provisions, and during the following days the peasantry stream in with enormous files of waggons loaded with wine and drawn by several oxen, so that, in spite of the re-established guard, it is necessary to let them enter all day without paying the dues; it is only on that these can again be collected. — The same thing occurs in the southern provinces, where the principal imposts are levied on provisions. There also the collections are suspended in the name of public authority. At Agde, “the people, considering the so-called will of the King as to equality of classes, are foolish enough to think that they are everything and can do everything;” thus do they interpret in their own way and in their own terms the double representation which is accorded to the Third-Estate. They threaten the town, consequently, with general pillage if the prices of all provisions are not reduced, and if the duties of the province on wine, fish, and meat are not suppressed; again, “they wish to nominate consuls who have sprung up out of their body,” and the bishop, the lord of the manor, the mayor and the notables, against whom they forcibly stir up the peasantry in the country, are obliged to proclaim by sound of trumpet that their demands shall be granted. Three days afterwards they exact a diminution of one-half of the tax on grinding, and go in quest of the bishop who owns the mills. The prelate, who is ill, sinks down in the street, and seats himself on a stone; they compel him forthwith to sign an act of renunciation, and hence “his mill, valued at 15,000 livres, is reduced to 7,500 livres.” — At Limoux, under the pretext of searching for grain, they enter the houses of the comptroller and tax contractors, carry off their registers, and throw them into the water along with the furniture of their clerks. — In Provence it is worse; for most unjustly, and through inconceivable imprudence, the taxes of the towns are all levied on flour; it is therefore to this impost that the dearness of bread is directly attributed; hence the fiscal agent becomes a manifest enemy, and revolts on account of hunger are transformed into insurrections against the State.

Here, again, political novelties are the spark that ignites the mass of gunpowder; everywhere, the uprising of the people takes place on the very day on which the electoral assembly meets; from forty to fifty riots occur in the provinces in less than a fortnight. Popular imagination, like that of a child, goes straight to its mark; the reforms having been announced, people think them accomplished, and, to make sure of them, steps are at once taken to carry them out; now that we are to have relief, let us relieve ourselves. “This is not an isolated riot as usual,” writes the commander of the troops; “here the faction is united and governed by uniform principles; the same errors are diffused through all minds. The principles impressed on the people are that the King desires equality; no more bishops or lords, no more distinctions of rank, no tithes, and no seignorial privileges. Thus, these misguided people fancy that they are exercising their rights, and obeying the will of the King.” The effect of sonorous phrases is apparent; the people have been told that the States-General were to bring about the “regeneration of the kingdom;” the inference is “that the date of their assembly was to be one of an entire and absolute change of conditions and fortunes.” Hence, “the insurrection against the nobles and the clergy is as active as it is widespread.” “In many places it was distinctly announced that there was a sort of war declared against landowners and property” and “in the towns as well as in the rural districts the people persist in declaring that they will pay nothing, neither taxes, duties, nor debts.” — Naturally, the first assault is against the piquet, or meal-tax. At Aix, Marseilles, Toulon, and in more than forty towns and market-villages, this is summarily abolished; at Aupt and at Luc nothing remains of the weighing-house but the four walls; at Marseilles the house of the slaughter-house contractor, at Brignolles that of the director of the leather excise, are sacked: the determination is “to purge the land of excise-men.” — This is only a beginning; bread and other provisions must become cheap, and that without delay. At Aries, the corporation of sailors, presided over by M. de Barras, consul, had just elected its representatives: by way of conclusion to the meeting, they pass a resolution insisting that M. de Barras should reduce the price of all comestibles, and, on his refusal, they “open the window, exclaiming, ‘We hold him, and we have only to throw him into the street for the rest to pick him up.’ ” Compliance is inevitable. The resolution is proclaimed by the town-criers, and at each article which is reduced in price the crowd shout, “Vive le Roi, vive M. Barras!” — One must yield to brute force. But the inconvenience is great; for, through the suppression of the meal-tax, the towns have no longer a revenue; and, on the other hand, as they are obliged to indemnify the butchers and bakers, Toulon, for instance, incurs a debt of 2,500 livres a day.

In this state of disorder, woe to those who are under suspicion of having contributed, directly or indirectly, to the evils which the people endure! At Toulon a demand is made for the head of the mayor, who signs the tax-list, and of the keeper of the records; they are trodden under foot, and their houses are ransacked.…

And then things really went to hell.

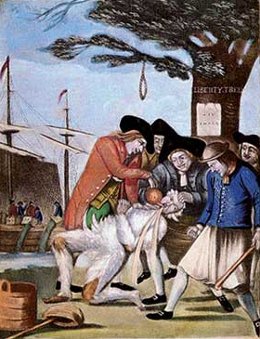

, I find a list of thirty-six committees or municipal bodies which, within a radius of fifty leagues around Paris, refuse to ensure the collection of taxes. One of them tolerates the sale of contraband salt, in order not to excite a riot. Another takes the precaution to disarm the employés in the excise department. In a third the municipal officers were the first to provide themselves with contraband salt and contraband tobacco. At Peronne and at Ham, the order having come to restore the toll-houses, the people destroy the soldiers’ quarters, conduct all the employés to their homes, and order them to leave within twenty-four hours, under penalty of death. After twenty months’ resistance Paris will end the matter by forcing the National Assembly to give in and by obtaining the final suppression of its octroi — Of all the creditors whose hand each one felt on his shoulders, that of the exchequer was the heaviest, and now it is the weakest; hence this is the first whose grasp is to be shaken off; there is none which is more heartily detested or which receives harsher treatment. Especially against collectors of the salt-tax, custom-house officers, and excisemen the fury is universal. These, everywhere, [footnote: “…Discourse of a deputation from Anjou: ‘Sixty thousand men are armed; the harriers have been destroyed, the clerks’ horses have been sold by auction; the employés have been told to withdraw from the province within eight days. The inhabitants have declared that they will not pay taxes so long as the salt-tax exists.’ ”] are in danger of their lives and are obliged to fly. At Falaise, in Normandy, the people threaten to “cut to pieces the director of the excise.” At Baignes, in Saintonge, his house is devastated and his papers and effects are burned; they put a knife to the throat of his son, a child six years of age, saying, “Thou must perish that there may be no more of thy race.” For four hours the clerks are on the point of being torn to pieces; through the entreaties of the lord of the manor, who sees scythes and sabres aimed at his own head, they are released only on the condition that they “abjure their employment.” — Again, for , insurrections break out by hundreds, like a volley of musketry, against indirect taxation. From the Intendant of Champagne reports that “the uprising is general in almost all the towns under his generalship.” On the Intendant of Alençon writes that, in his province, “the royal dues will no longer be paid anywhere.” On , M. Necker states to the National Assembly that in the two intendants’ districts of Caen and Alençon it has been necessary to reduce the price of salt one-half; that “in an infinity of places” the collection of the excise is stopped or suspended; that the smuggling of salt and tobacco is done by “convoys and by open force” in Picardy, in Lorraine, and in the Trois-Evêchés; that the indirect tax does not come in, that the receivers-general and the receivers of the taille are “at bay” and can no longer keep their engagements. The public income diminishes from month to month; in the social body, the heart, already so feeble, faints; deprived of the blood which no longer reaches it, it ceases to propel to the muscles the vivifying current which restores their waste and adds to their energy.

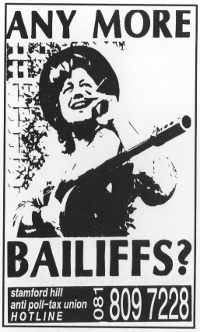

“All controlling power is slackened,” says Necker, “everything is a prey to the passions of individuals.” Where is the power to constrain them and to secure to the State its dues? The clergy, the nobles, wealthy townsmen, and certain brave artisans and farmers, undoubtedly pay, and even sometimes give spontaneously. But in society those who possess intelligence, who are in easy circumstances and conscientious, form a small select class — the great mass is egotistic, ignorant, and needy, and lets its money go only under constraint; there is but one way to collect the taxes, and that is to extort them. From time immemorial, direct taxes in France have been collected only by bailiffs and seizures; which is not surprising, as they take away a full half of the net income. Now that the peasants of each village are armed and form a band, let the collector come and make seizures if he dare! — “Immediately after the decree on the equality of the taxes,” writes the provincial commission of Alsace, “the people generally refused to make any payments, until those who were exempt and privileged should have been inscribed on the local lists.” In many places the peasants threaten to obtain the reimbursement of their instalments, while in others they insist that the decree should be retrospective and that the new rate-payers should pay for the past year. “No collector dare send an official to distrain; none that are sent dare fulfill their mission.” — “It is not the good bourgeois” of whom there is any fear, “but the rabble who make the tatter and every one else afraid of them;” resistance and disorder everywhere come from “people that have nothing to lose.”

In Touraine, “as the publication of the tax-rolls takes place, riots break out against the municipal authorities; they are forced to surrender the rolls they have drawn up, and their papers are torn up.”

As the revolutionary government consolidated power, displacing the King and the Church, things settled down… not. Here’s how things looked :

The fear of starvation is only the sharper form of a more general passion, which is the desire of possession, and the determination not to give up the possessions attained. No popular instinct had been longer, more rudely, more universally tried under the ancient regime; and there is none which gushes out more readily under constraint, none which requires a higher or broader public barrier, or one more entirely constructed of solid blocks, to keep it in check. Hence it is that this passion from the commencement breaks down or engulfs the slight and low boundaries, the tottering embankments of crumbling earth between which the Constitution pretends to confine it. — The first flood sweeps away the pecuniary claims of the State, of the clergy, and of the noblesse. The people regard them as abolished, or, at least, they consider their debts discharged. Their idea, in relation to this, is formed and fixed; for them it is that which constitutes the Revolution. The people have no longer a creditor; they are determined to have none, they will pay nobody, and first of all, they will make no further payment to the State.

On the , the day of the Federation, the population of Issoudun, in Touraine, solemnly convoked for the purpose, had just taken the solemn oath which was to ensure public peace, social harmony, and respect for the law for evermore. [footnote: “ ‘Archives Nationales,’ H, 1453. Correspondence of M. de Bercheny, , and . — The same disposition lasted. An insurrection occurred in Issoudun after , against the combined imposts. Seven or eight thousand vine-dressers burnt the archives and tax-offices and dragged an employé through the streets, shouting out at each street-lamp, ‘Let him be hung!’ The general sent to repress the outbreak entered the town only through a capitulation; the moment he reached the Hôtel-de-Ville a man of the Faubourg de Rome put his pruning-hook around his neck, exclaiming, ‘No more clerks where there is nothing to do!’ ”] Here, probably, as elsewhere, arrangements had been made for an affecting ceremonial; there were young girls dressed in white, and learned and impressionable magistrates were to pronounce philosophical harangues. All at once they discover that the people gathered on the public square are provided with clubs, scythes, and axes, and that the National Guard will not prevent their use; on the contrary, the Guard itself is composed almost wholly of vine-dressers and others interested in the suppression of the duties on wine, of coopers, innkeepers, workmen, carters of casks, and others of the same stamp, all rough fellows who have their own way of interpreting the Social Contract. The whole mass of decrees, acts, and rhetorical flourishes which are dispatched to them from Paris, or which emanate from the new authorities, are not worth a half-penny tax maintained on each bottle of wine. There are to be no more excise duties; they will only take the civic oath on this express condition, and that very evening they hang, in effigy, their two deputies, who “had not supported their interests” in the National Assembly. A few months later, of all the National Guard called upon to protect the clerks, only the commandant and two officers respond to the summons. If a docile taxpayer happens to be found, he is not allowed to pay the dues; this seems a defection and almost treachery. An entry of three puncheons of wine having been made, they are stove in with stones, a portion is drunk, and the rest taken to the barracks to debauch the soldiers; M. de Sauzay, commandant of the “Royal Roussillon,” who was bold enough to save the clerks, is menaced, and for this misdeed he barely escapes being hung himself. When the municipal body is called upon to interpose and employ force, it replies that “for so small a matter, it is not worth while to compromise the lives of the citizens,” and the regular troops sent to the Hôtel-de-Ville are ordered by the people not to go except with the but-ends of their muskets in the air. Five days after this the windows of the excise office are smashed, and the public notices are torn down; the fermentation does not subside, and M. de Sauzay writes that a regiment would be necessary to restrain the town. At Saint-Amand the insurrection breaks out violently, and is only put down by violence. At Saint-Etienne-en-Forez, Berthéas, a clerk in the excise office, falsely accused of monopolizing grain, is fruitlessly defended by the National Guard; he is put in prison, according to the usual custom, to save his life, and, for greater security, the crowd insist on his being fastened by an iron collar. But, suddenly changing its mind, it breaks upon the door and drags him to death. Stretched on the ground, his head still moves and he raises his hand to it, when a woman, picking up a large stone, smashes his skull. — These are not isolated occurrences. During , the tax offices are burnt in almost every town in the kingdom. In vain does the National Assembly order their reconstruction, insist on the maintenance of duties and octrois, and explain to the people the public needs, pathetically reminding them, moreover, that the Assembly has already given them relief; — the people prefer to relieve themselves instantly and entirely. Whatever is consumed must no longer be taxed, either for the benefit of the State or for that of the towns. “Entrance dues on wine and cattle,” writes the municipality of Saint-Etienne, “scarcely amount to anything, and our powers are inadequate for their enforcement.” At Cambrai, two successive outbreaks compel the excise office and the magistracy of the town to reduce the duties on beer one-half. But “the evil, at first confined to one corner of the province, soon spreads;” the grands baillis of Lille, Douai, and Orchies write that “we have hardly a bureau which has not been molested, and in which the taxes are not wholly subject to popular discretion.” Those only pay who are disposed to do so, and, consequently, “greater fraud could not exist.” The taxpayers, indeed, cunningly defend themselves, and find plenty of arguments or quibbles to avoid paying their dues. At Cambrai they allege that, as the privileged now pay as well as the rest, the Treasury must be rich enough. At Noyon, Ham, and Chauny, and in the surrounding parishes, the butchers, innkeepers, and publicans combined, who have refused to pay excise duties, pick flaws in the special decree by which the Assembly subjects them to the law, and a second special decree is necessary to circumvent these new legists. The process at Lyons is simpler. Here the thirty-two sections appoint commissioners; these decide against the octroi, and request the municipal authorities to abolish it. They must necessarily comply, for the people are at hand and are furious. Without waiting, however, for any legal measures, they take the authority on themselves, rush to the toll-houses and drive out the clerks, while large quantities of provisions, which “through a singular predestination” were waiting at the gates, come in free of duty.

The Treasury defends itself as it best can against this universally bad disposition of the tax-payer, against these irruptions and infiltrations of fraud; it repairs the dyke where it has been carried away, stops up the fissures and again resumes collections. But how can these be regular and complete in a State where the courts dare not condemn delinquents, where public force dares not support the courts, [footnote: “ ‘Archives Nationales,’ F. 7, 3255. Letter of the Minister, , to the Directory of Rhone-et-Loirc. ‘The King is informed that, throughout your department, and especially in the districts of Saint-Etienne and Monthrison, license is carried to the extreme; that the judges dare not prosecute; that in many places the municipal officers are at the head of the disturbances; and that, in others, the National Guard do not obey requisitions.’…] where popular favour protects the most notorious bandits and the worst vagabonds against the tribunals and against the public powers? At Paris, where, after eight months of impunity, proceedings are begun against the pillagers who, on , set fire to the tax offices, the officers of the election, “considering that their audiences have become too tumultuous, that the thronging of the people excites uneasiness, that threats have been uttered of a kind calculated to create reasonable alarm,” are constrained to suspend their sittings and refer matters to the National Assembly, while the latter, considering that “if prosecutions are authorised in Paris it will be necessary to authorise them throughout the kingdom,” decides that it is best “to veil the statue of the Law.” — Not only does the Assembly veil the statue of the Law, but it takes to pieces, remakes, and mutilates it, according to the requirements of the popular will; and, in the matter of indirect imposts, all its decrees are forced upon it. The outbreak against the salt impost was terrible from the beginning; sixty thousand men in Anjou alone combined to destroy it, and the price of salt had to be reduced from sixteen to six sous. The people, however, are not satisfied with this. This monopoly has been the cause of so much suffering that they are not disposed to put up with any remains of it, and are always on the side of the smugglers against the excise officers. In , at Béziers, thirty-two employés, who had seized a quantity of contraband salt on the persons of armed smugglers, are pursued by the crowd to the Hôtel-de-Ville; the consuls decline to defend them and run away; the troops defend them, but in vain. Five are tortured, horribly mutilated, and then hung. In , Necker states that, according to the returns of , the deficit in the salt-tax amounts to more than four millions a month, “which is four-fifths of the ordinary revenue, while the tobacco monopoly is no more respected than that of salt. At Tours, the bourgeois militia refuse to give assistance to the employés, and “openly protect smuggling,” “and contraband tobacco is publicly sold at the fair, under the eyes of the municipal authorities, who dare make no opposition to it.” All receipts, consequently, diminish at the same time. [footnote: “Mercure de France, (sitting of ). M. Lambert, Comptroller-General of the Finances, informs the Assembly of ‘the obstacles which continual outbreaks, brigandage, and the maxims of anarchical freedom impose, from one end of France to the other, on the collection of the taxes. On one side, the people are led to believe that, if they stubbornly refuse a tax contrary to their rights, its abolition will be secured. Elsewhere, smuggling is openly carried on by force; the people favour it, while the National Guards refuse to act against the nation. In other places hatred is excited, and divisions between the troops and the overseers at the toll-houses: the latter are massacred, the bureaus are pillaged, and the prisons are forced open.’ — Memorial to the National Assembly by M. Necker, .”] , the general collections amount to one hundred and twenty-seven millions instead of one hundred and fifty millions; the dues and excise combined return only thirty-one, instead of fifty millions. The streams which filled the public exchequer are more and more obstructed by popular resistance, and under the popular pressure, the Assembly ends by closing them entirely. In , it abolishes salt duties, internal customs-duties, taxes on leather, on oil, on starch, and the stamp of iron. In , it abolishes octrois and entrance-dues in all the cities and boroughs of the kingdom, all the excise duties and those connected with the excise, especially all taxes which affect the manufacture, sale, or circulation of beverages. The people have at last carried everything, and on , the day of the application of the decree, the National Guard of Paris parades around the walls playing patriotic airs. The cannon of the Invalides and those on the Pont-Neuf thunder out as if for an important victory. There is an illumination in the evening, there is drinking all night, a universal revel. Beer, indeed, is to be had at three sous the pot, and wine at six sous a pint, which is a reduction of one-half; no conquest could be more popular, since it brings intoxication within easy reach of all topers.

The object, now, is to provide for the expenses which have been defrayed by the suppressed octrois. In , the octroi of Paris had produced 35,910,859 francs, of which 25,059,446 went to the State, and 10,851,413 went to the city. How is the city going to pay for its watch, the lighting and cleaning of its streets, and the support of its hospitals? What are the twelve hundred other cities and boroughs going to do which are brought by the same stroke to the same situation? What will the State do, which, in abolishing the general revenue from all entrance-dues and excise, is suddenly deprived of two-fifths of its revenue? — In , when the Assembly suppressed the salt and other duties, it established in the place of these a tax of fifty millions, to be divided between the direct imposts and dues on entrance to the towns. Now, consequently, that the entrance-dues are abolished, the new charge falls entirely upon the direct imposts. Do returns come in, and will they come in? — In the face of so many outbreaks, any indirect taxation is, certainly, difficult to collect. Nevertheless it is not so repulsive as the other because the levies of the State disappear in the price of the article, the hand of the Exchequer being hidden by the hand of the dealer. The Government clerk formerly presented himself with his stamped paper and the seller handed him the money without much grumbling, knowing that he would soon be more than reimbursed by his customer: the indirect tax is thus collected. Should any difficulty arise, it is between the dealer and the taxpayer who comes to his shop to lay in his little store; the latter grumbles, but it is at the high price which he feels, and possibly at the seller who pockets his silver; he does not find fault with the clerk of the Exchequer, whom he does not see and who is not then present. In the collection of the direct tax, on the contrary, it is the clerk himself whom he sees before him, who abstracts the precious piece of silver. This authorised robber, moreover, gives him nothing in exchange; it is an entire loss. On leaving the dealer’s shop he goes away with a jug of wine, a pot of salt, or similar commodities; on leaving the tax office he has nothing in hand but an acquittance, a miserable bit of scribbled paper. — But now he is master in his own commune, an elector, a National Guard, mayor, the sole authority in the use of armed force, and charged with his own taxation. Come and ask him to unearth the buried mite on which he has set all his heart and all his soul, the earthen pot wherein he has deposited his cherished pieces of silver one by one, and which he has laid by for so many years at the cost of so much misery and fasting, in the very face of the bailiff, in spite of the prosecutions of the sub-delegate, commissioner, collector, and clerk!

, the general returns, the taille and its accessories, the poll-tax and “twentieths,” instead of yielding 161,000,000 francs, yield but 28,000,000 francs in the provinces which impose their own taxes (pays d’Etats); instead of 28,000,000 francs, the Treasury obtains but 6,000,000. On the patriotic contribution which was to deduct one quarter of all incomes over four hundred livres, and to levy two and a half per cent, on plate, jewels, and whatever gold and silver each person has in reserve, the State received 9,700,000 francs. As to patriotic gifts, their total, comprising the silver buckles of the deputies, reaches only 361,587 francs; and the closer our examination into the particulars of these figures, the more do we see the contributions of the villager, artisan, and former subjects of the taille diminish. — Since , the privileged classes, in fact, appear in the tax-rolls, and they certainly form the class which is best off, the most alive to general ideas and the most truly patriotic. It is therefore probable that, of the forty-three millions of returns from the direct imposts and from the patriotic contribution, they have furnished the larger portion, perhaps two-thirds of it, or even three-quarters. If this be the case, the peasant, the former tax-payer, gave nothing or almost nothing from his pocket during the first year of the Revolution. For instance, in regard to the patriotic contribution, the Assembly left it to the conscience of each person to fix his own quota; at the end of six months, consciences are found too elastic, and the Assembly is obliged to confer this right on the municipalities. The result is that this or that individual who taxed himself at forty-eight livres, is taxed at a hundred and fifty; another, a cultivator, who had offered six livres, is judged to be able to pay over one hundred. Every regiment contains a small number of select brave men, and it is always these who are ready to advance under fire. Every State contains a select few of honest men who advance to meet the tax-collector. Some effective constraint is essential in the regiment to supply those with courage who have but little, and in the State to supply those with probity who do not possess it. Hence, during , the patriotic contribution furnishes but 11,000,000 livres. , out of the forty thousand communal tax-rolls which should provide for it, there are seven thousand which are not yet drawn up; out of 180,000,000 livres which it ought to produce, there are 70,000,000 livres which are still due. — The resistance of the tax-payer produces a similar deficit, and similar delays in all branches of the national income. In , a deputy declares in the tribune that “out of thirty-six millions of imposts which ought to be returned each month only nine have been received.” In , a reporter on the budget states that the receipts, which should amount to forty or forty-eight millions a month, do not reach eleven millions and a half. On , there remains still due on the direct taxes of one hundred and seventy-six millions. — It is evident that the people struggle with all their might against the old taxes, even authorised and prolonged by the Constituent Assembly, and all that is obtained from them is wrested from them.

Will the people be more docile under the new taxation? The Assembly exhorts them to be so and shows them how, with the relief they have gained and with the patriotism they ought to possess, they can and should discharge their dues. The people are able to do it because, having got rid of tithes, feudal dues, the salt-tax, octrois and excise duties, they are in a comfortable position. They should do so, because the taxation adopted is indispensable to the State, equitable, assessed on all in proportion to their fortune, collected and expended under rigid scrutiny, without perversion or waste, according to precise, clear, periodical and audited accounts. No doubt exists that, after , the date when the new financial scheme comes into operation, each tax-payer will gladly pay as a good citizen, and the two hundred and forty millions of the new tax on real property, and the sixty millions of that on personal property, leaving out the rest — registries, license, and customs duties — will flow in regularly and easily of their own accord.

Unfortunately, before the tax-gatherer can collect the first two levies these have to be assessed, and as there are complicated writings and formalities, claims to settle amidst great resistance and local ignorance, the operation is indefinitely prolonged. The personal and land-tax schedule of is not transmitted to the departments by the Assembly until . The departments do not distribute it among the districts until . It is not distributed by the districts among the communes before . Thus in it is not yet distributed to the tax-payers by the communes; from which it follows that on the budget of , the tax-payer has paid nothing. — At last, in , everybody begins to receive this assessment. It would require a volume to set forth the partiality and dissimulation of these assessments. In the first place the office of assessor is one of danger; the municipal authorities, whose duty it is to assign the quotas, are not comfortable in their town quarters. Already, in , [footnote: “ ‘Archives Nationales,’ H, 1453. Correspondence of M. de Bercheny, , &c. — F. 7, 3226. Letters of Chenantin, cultivator, , also of the procureur-syndic, . — F. 7, 3202. Letter of the Minister of Justice, Duport, . ‘The utter absence of public force in the district of Montargis renders every operation of the Government and all execution of the laws impossible. The arrears of taxes to be collected is here very considerable, white all proceedings of constraint are dangerous and impossible to execute, owing to the fears of the bailiffs, who dare not perform their duties, and the violence of the tax-payers, on whom there is no check.’ ”] the municipal officers of Monbazon have been threatened with death if they dared to tax industrial pursuits on the tax-roll, and they escaped to Tours in the middle of the night. Even at Tours, three or four hundred insurgents of the vicinity, dragging along with them the municipal officers of three market-towns, come and declare to the town authorities “that for all taxes they will not pay more than forty-five sous per household.” I have already narrated how, in , in the same department, “they kill, they assassinate the municipal officers” who presume to publish the tax-rolls of personal property. In Creuse, at Clugnac, the moment the clerk begins to read the document, the women spring upon him, seize the tax-roll, and “tear it up with countless imprecations;” the municipal council is assailed, and two hundred persons stone its members, one of whom is thrown down, has his head shaved, and is promenaded through the village in derision. — When the small tax-payer defends himself in this manner, it is a warning that he must be humoured. The assessment, accordingly, in the village councils is made amongst a knot of cronies. Each relieves himself of the burden by shoving it off on somebody else. “They tax the large proprietors, whom they want to make pay the whole tax.” The noble, the old seigneur, is the most taxed, and to such an extent that in many places his income does not suffice to pay his quota. — In the next place they make themselves out poor, and falsify or elude the prescriptions of the law. “In most of the municipalities, houses, tenements, and factories are estimated according to the value of the area they cover, and considered as land of the first class, which reduces the quota to almost nothing.” And this fraud is not practised in the villages alone. “Communes of eight or ten thousand souls might be cited which have arranged matters so well amongst themselves in this respect that not a house is to be found worth more than fifty sous.” — Last expedient of all, the commune defers as long as it can the preparation of its tax-rolls. On , out of 40,211, there are only 2,560 which are complete; on , the schedules are not made out in 4,800 municipalities, and it must be noted that all this relates to a term of administration which has been finished for . At , there are more than six thousand communes which have not yet begun to collect the land-tax of , and more than fifteen thousand communes which have not yet begun to collect the personal tax; the Treasury and the departments have not yet received 152,000,000 francs, there being still 222,000,000 to collect. On , there still remains due on the same period 161,000,000 francs, “while of the 50,000,000 assessed in , to replace the salt-tax and other suppressed duties, only 2,000,000 have been collected. Finally, at the same date, out of the two direct taxes of , which should produce 300,000,000, less than 4,000,000 have been received. — It is a maxim of the debtor that he must put off payment as long as possible. Whoever the creditor may be, the State or a private individual, a leg or a wing may be saved by dint of procrastination. The maxim is true, and, on this occasion, success once more demonstrates its soundness. During , the peasant begins to discharge a portion of his arrears, but it is with assignats. In , the assignats diminish thirty-four, forty-four, and forty-five per cent. in value; in , forty-seven and fifty per cent.; in , fifty-four, sixty, and sixty-seven per cent. Thus has the old credit of the State melted away in its hands; those who have held on to their crowns gain fifty per cent, and more. Again, the greater their delay the more their debts diminish, and already, on the strength of this, the way to release themselves at half-price is found.

If some tribunal is disposed to enforce the law, it is to no purpose; it takes the risk, either of not being allowed to give judgment, or of being constrained to reverse its decision. At Paris the judgment prepared against the incendiaries of the tax-offices could not be given.…

Sounds like quite a party.