And just when I’ve finished crowing about how these nice tax cuts will take billions of dollars from the politicians, along comes Daniel Shaviro to explain to me how tax cuts actually make the government bigger.

How you can resist funding the government → about the IRS and U.S. tax law/policy → the “starve the beast” theory

I mentioned Daniel Shaviro’s contention that tax cuts actually make the government bigger. , Jonathan Baron and Edward J. McCaffery make the case for “starving the beast:”

I’m one of those sad, pathetic creatures who is occasionally gripped with visceral loathing for Dubya in spite of himself. I shudder with disgust when I hear him try to speak. My eyes water with anguish when I discover some new example of suffering his foreign policy is causing. If I pay too close attention, I’m a wreck.

But I’ve always had a sort of shameful respect for his tax policy. He’s been doing on an enormous scale pretty much what I’ve been trying to do on a feeble one.

I’ve taken myself off of the income tax rolls and I’ve done what I can do reduce the amount of money I provide for the government to pay with. Dubya, meanwhile, has taken millions of people off the income tax rolls, and has slashed government revenue with a vengeance.

Needless to say, I’m conflicted.

I think I’d always assumed that if the government was taking in less money, it’d eventually (once it maxed out the credit cards) have to shrink. That while Dubya’s certainly no government-shrinker himself, his policies would eventually have that effect. This is that “starve the beast” theory that the Norquist wing of Republican tax cutters has made notorious.

Daniel Shaviro thinks we’ve got it backwards. In his paper — The Bush Administration’s Huge Tax Cuts: Steps Towards Bigger Government? — he says, “the idea that the tax cuts would make the government smaller seems to have rested on spending illusion, or confusion between the actual size of government, in terms of its allocative and distributional effects, and the observed dollar flows that are denominated ‘taxes’ and ‘spending.’ ”

The size of government, Shaviro notes, is not measured only by the amount of money it inhales and exhales, but by the amount of control it has over other parts of society and the economy and how it chooses to honor or disregard its debts and obligations. As a simple example: If the government forces Peter to pay Paul, it is no smaller than if it taxes Peter and subsidizes Paul.

Shaviro believes that the indebting effects of Dubya’s tax policy will lead to a massive “wealth redistribution from younger to older generations.” By incurring debts now (obligations to those who are on or will soon be on Social Security, bonds to pay for war and government), the government is either forcing future taxpayers to pay for the current generation’s folly, or forcing future taxpayers to renege on this debt — either one of which will be a huge, government-mandated transfer of wealth.

There’s no substitute, it turns out, for reducing the size of government directly, says Shaviro — trying to “starve” it only makes it bigger:

[T]he case becomes quite powerful that the tax cuts will probably, over time, make the government larger on balance. The overall package is one of much more redistribution to older generations, accompanied by only a possibility of commensurately reduced allocative effects.

If one looks beyond the tax cuts themselves to the overall budget policy of the Bush Ⅱ Administration, the case for an increase in the size of government becomes almost irrefutable. This, after all, is an Administration that in its first two years increased Federal outlays by $222 billion, or from 18.4 percent to 19.5 percent of gross domestic product. Only about forty percent of this increase was for defense spending, suggesting that one could not attribute all (or even most) of it to the events of even if one assumed that any Administration would have responded to those events in the same way. By its third year, the Administration was busy proposing a new prescription drug benefit in Medicare that was expected to cost $400 billion over the following ten years.

If nothing else, this proposal pretty much exploded any notion that the tax cuts were aimed at shrinking the government’s allocative effects via Medicare, since simply recouping the expansion of government from this new benefit would be a tall task. Rather, the Administration appears to be seeking short-term political advantage and favors for particular groups, merely deceptively clothed in antigovernment rhetoric. Then again, conservative ideologues of the Norquist genre, even when opposed to the Bush Administration’s spending increases, appear no less convinced than it (if it is sincere) that tax cuts somehow have a greater impact on the size of government than spending increases. They evidently do not, or choose not to, understand the long-term budget constraint, under which a dollar of added government outlays today, if it does not reduce expected future outlays (which more likely it would increase, given the effect on political expectations) implies added taxes with a present value of a dollar.

Those of us still hoping for proof of the “starve the beast” theory of shrinking government in the future by running up debts today have cause to get our hopes up a little higher this week:

Alas, the article goes on to set up the math for us, and these cuts don’t really amount to much:

The Pentagon’s budget for , was $310 billion. For , which was approved before the attacks, it was $317 billion, and in subsequent years, rose to $355 billion, $368 billion, and $416 billion. These figures do not include supplemental appropriations for war-fighting efforts.

In , the Pentagon estimated it would need $424 billion for and $445 billion for , not including supplemental funding. Officials say those figures could both end up shrinking by $10 billion and that similar cuts could occur in subsequent years.

So, the Pentagon’s budget goes up by a third in the years since Dubya took office but starting now… it won’t rise nearly so fast. Well, it’s a start.

The actual numbers for and were $536 billion and $527 billion, not including war supplementals.

Take money away from the government now, by tax resistance or tax evasion or tax cuts, and eventually they’ll have to start borrowing, and then start spending less, and the government will get a little bit smaller and hopefully a little less bothersome as a result.

That’s the dream of the tax resister, and the “starve the beast” fantasy of the conservative tax-cut advocate.

Daniel Shaviro thinks we’re mistaken. The big problem is that we naïvely “use… the terms ‘taxes’ and ‘spending’ as proxies for determining the size of government.”

Thus, if the government were to give me $1 billion which I immediately handed back, simplistic idiots would say: “There’s just been a billion dollars of taxes and spending!” I would say that really nothing has happened.

No idle hypothetical — Social Security, for example, has aspects of this, although there is a greater time lag and the cash you get back may not equal, in time-adjusted value, the cash you put back. But this means it’s the aspects of non-equivalence, not the gross cash flows each way, that determine how significant the whole thing is.

The size of government, I’d say, is a concept that, in the budgetary realm, involves trying to quantify the effects of government policy, relative to some baseline that has to be specified, on allocation and distribution — on what we have and who has it. (I limit this to the budgetary realm because issues such as civil liberties operate in different dimensions.)

Once you take this perspective, the utter inadequacy of discerning how much the government is doing from the number of dollars associated with discrete and often offsetting cash flows becomes pretty clear.

Against this background, what does “starve the beast” accomplish even if there are large spending cuts in future years? (Note: there will almost certainly be large tax increases as well.) Point 1: It definitely increases redistribution, by handing vast sums of extra money to older generations at the expense of younger generations. (Older generations were huge net winners even before the whole exercise started.) Point 2: It probably increases government-induced economic distortion, what with the heightened disparity between tax rates in different periods, the instability and risk of fiscal crisis throughout the adjustment process (which may become chronic rather than coming to an end), etc.

Next time somebody talks about Big Government Democrats and salutes the Dubya Squad for starving the beast with its tax cuts, point them at this article in which Dead-Eye Dick Cheney brags that the Bush administration’s tax cuts have boosted federal government revenue:

Vice President Cheney said Thursday night that the verdict is in before the Bush administration’s new tax analysis shop has even opened for business: Tax cuts boost federal government revenue.

That assertion won applause from his audience at the Conservative Political Action Conference…

Apologies for my recent span of postlessness. My excuses include attending a wedding out of town, starting up again at my day job, and reading a dense and interesting book — Evil and Human Agency — which I’ll review here when I finish it, if I can wait until then.

For news, I have two bits of disillusionment for those of you who still cling to the Democratic and Republican parties (I know you’re out there, because I keep running in to you).

First: for those of you Republicans who know you have much to be ashamed of but think you can at least be proud of the beast-starving, tax-cutting part of your party — think again. The Beast Ain’t Starving:

Federal revenue collections hit an all-time high in , contributing to a further improvement in the budget deficit for .… , tax revenues total $1.505 trillion, an increase of 11.2% over . That figure includes $383.6 billion collected in , the largest monthly tax collection on record. Tax collections swell in April every year as individuals file their tax returns by the deadline. For , revenue collections and government spending are at all-time highs.

And secondly, for those of you who still can’t seem to help but be Democrats, please note: the military budget is as bloated as ever now that the donkey party holds the purse strings:

[I]f anyone thought the Democrats might reassess the nation’s defense needs or the Pentagon’s way of doing business, think again. The Cold War may be long over, but America’s Cold War military machine is intact and well-oiled.

This $504 billion—measured in real terms (i.e., adjusting for inflation) — falls only a few billion short of the largest military budget in U.S. history, back in , when America was embarking on its Cold War rearmament campaign and fighting a war in Korea.

One difference: The budget included the cost of fighting in Korea. The budget does not include the cost of fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.…

A half-trillion dollars exceeds the military budgets of all the world’s other nations combined.

So the national debt has never been higher and this year’s federal budget deficit may be a record-breaker too. Washington has just formally taken on a bunch of debt with the housing bailouts, and Congress is thinking of giving away money to everyone in the form of another stimulus package. The economy is in the receiving end of the outhouse, which means that tax receipts will be low this year (fewer capital gains in the income-tax paying classes, lower corporate profits, more people unemployed). Meanwhile, both frontrunner presidential candidates are promising to cut taxes and increase the size of the military and give everybody a pony.

All of which might make you wonder whether in fact there are any sorts of reality-based restraints on federal spending at all. If the government can just spend as much as it wants without bothering to come up with any reasonable claim to be raising the money it’s spending, why does it bother to go through the farce of raising money at all?

Jeffrey Tucker at the Mises Institute tries to get to the bottom of this in his article “Why Taxes Don’t Matter Much Anymore”. Excerpt:

Why is it that talk of tax policy doesn’t seem to have a relationship to policy generally? Whether it’s a bailout of subprime mortgage holders, large investment banks, or going to war, whether or not the resources exist to do these wonders rarely enters into the equation. Why is it that tax cuts don’t curb the government? And why do politicians not feel the need to tax us more when they spend more?

You might at first say that the answer is simple: they just go into debt by running an annual deficit. And the debt today stands at some figure that has no real meaning, because it is too high for us to even contemplate. What does it really mean that the debt is $5 trillion or $10 trillion? It might as well be an infinite amount for all we know. At least that’s how the political class acts.

Reference to the debt only begs the question. You and I have to pay our debts. We cannot run up an infinite amount of it without getting into trouble and losing our creditworthiness. In the private sector, debt instruments are valued according to the prospect that the debts will be paid. The likelihood that it will be covered is reflected in the default premium. But the debt of the U.S. government doesn’t work that way. The bonds of the U.S. Treasury are the most secure investment there is. It is valued as if it will be paid no matter what.

If not through taxes, and if not through infinite debt, how is it that the U.S. government gets the money it wants regardless of other constraints?

Tucker suggests that the government, via the Fed, is essentially just powering up the printing presses — or, at least, implicitly keeping this option in reserve. Should push come to shove, the government will pay its debt by devaluing it (and everyone else’s dollars) to a manageable level. Or something like that. I dunno. When I hear libertarian types go on about the gold standard and the Fed and sound money and so forth my eyes glaze over and I get the same sort of feeling I get when I hear Kennedy assassination conspiracy theorists — maybe they’re right, but they sound a little batty, and I’ve got other things to do than educate myself enough about the issue to evaluate the arguments intelligently.

But whatever is the mechanism that makes these shenanigans possible, the fact that government growth and activity doesn’t seem to be at all restrained by government income poses the same challenge to (some varieties of) tax resisters that it has to advocates of the “starve the beast” theory of small-government. If you’re a tax resister because you hope that if enough people resisted their taxes, the government might be unable to do some of the nefarious things it does, or that the government might reform in some way in the hopes of winning back some of the revenue its lost to disgruntled ex-taxpayers, you may be fooling yourself.

Some links that have caught my eye:

- Derek Brett of Conscience and Peace Tax International explains how their campaign grew out of the international movement to recognize conscientious objection to military conscription, and how he sees the movement’s goals.

- Bruce Bartlett looks at the experimental evidence for the “starve the beast” theory, and thinks it disproven. In recent decades, revenue and tax cuts have coincided with the growth of government. Since tax reductions make government seem cheaper, people demand more of it, at least so goes the counter-theory. But I can’t help thinking that the experiment isn’t over yet, and as more of the federal budget goes to paying pensions and interest, the government may yet have to shrink.

- The IRS Oversight Board’s annual report is out. Not much new there, though.

Some tax resistance news in brief:

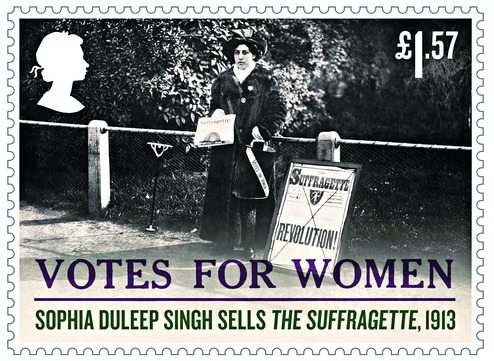

- British suffragette tax resister Sophia Duleep Singh now has a postage stamp in her honor.

- The Archibald Tuttle squad of the Den Plirono movement in Greece has done it again: reconnecting the power to the home of two nonagenarians whose power was cut by the state utility monopoly after they were no longer able to afford to pay the bill on their meager pensions.

- Frederick Burks, former White House staffer during the Dubya Squad years, and now a big conspiracy theory fan, has decided to give war tax resistance a try.

- Greek Orthodox Archbishop Theodosios has declared his intention to defy Jerusalem’s attempt to tax church property. The Archbishop has a history of clashing with Israel over Palestinian rights. The Jerusalem municipal government is looking to expand its tax base by taxing property owned by religious groups that is not largely used for religious purposes; the Greek Orthodox church has been shedding some of its Jerusalem property under suspicious circumstances. Theodosios says he believes these tax proposals, which largely target Christian groups, are “a deliberate attempt to extend [the occupation authorities’] control over the city of Jerusalem and to marginalize and weaken the Christian presence in particular, and the Arab Palestinian presence in general.” Jerusalem has already put liens on several churches to cover back taxes.

- In theory, you can make the federal government shrink in size and invasiveness and ambition by cutting its income through lower tax revenue. In reality, this “starve the beast” theory doesn’t seem to work. The growth of government spending and reach doesn’t seem to slow at all in reaction to fiscal pressure of this sort. Of course, experiments are hard to do in this context — would more revenue have resulted in even greater growth of the beast? Is the day of reckoning merely postponed, and inevitably the government will have to shrink? Still, it’s fair to say that the evidence for the ability of revenue restriction to shrink the growth of government, at least in the short-to-medium-term, is lacking.