When trying to bring new tax resisters into a movement, there are lots of hopeful short-cuts, but sometimes there is no substitute for addressing potential resisters individually: whether that be through letters, petitions, or face-to-face meetings.

- When the United States approved a billion-dollar military aid package to the government of Colombia in , the president of the Mennonite Church of Colombia, Peter Stucky, and Ricardo Esquivia, the director of that church’s Justapaz organization and the coordinator of the Evangelical Council of Colombia’s Human Rights and Peace Commission, wrote a letter to their sister churches in the U.S..

In that letter, they explained the disastrous consequences of fueling the civil war and the military wing of the war on drugs there, explained how the church there was trying to respond more productively to the crisis, and called on churches in the U.S. to do their part:

The American Mennonite Central Committee responded by urging taxpayers to redirect their taxes from the U.S. government to the Mennonite-run “Taxes for Peace” fund, which in turn would be dedicated that year to peace-building efforts in Colombia.In reality, the government of the United States, using the tax-payers money, is supporting the Colombian government in what we consider to be a negative form. This means that the message arriving from the North to the Colombian people becomes a message of death and destruction. For that reason we are calling the churches in the North to redeem their taxes, on one hand by demanding that the U.S. government invests this money in life-producing projects, and on the other hand by redirecting part of their taxes toward a different project in your community or the world that promotes abundant and dignified life, as our Lord Jesus Christ has commanded us.

- This sort of advocacy can be dangerous, as this next example will show.

In , R.W. Benner, a Mennonite minister, got worried reports from members of his congregation who were being told in no uncertain terms that they would buy so-called “Liberty Bonds” to support the U.S. war effort, or they would answer for their refusal.

Benner wrote to his bishop, L.J. Heatwole, who responded with a letter in which he reiterated the position of the church that Mennonite brethren “Do not aid or abet war in any form… [and] Contribute nothing to a fund that is used to run the war machine.”

He noted:

But he urged his fellow-Mennonites to keep the faith and to embrace this sort of martyrdom like good Christians. Benner conveyed this message to his flock. For this, both of them were charged under the Espionage Act and convicted. (To give you some idea of the railroading involved, Heatwole did not learn that a guilty plea had been entered on his behalf by his court-appointed attorney until after he appeared for the trial!)In a number of places where brethren have refused to contribute to the different war funds, outlandish threats have been made and in a few cases have been put into execution — such as, tar and feathering, painting houses yellow, decorating autos and buildings with flags to test them out on their principles of nonresistance.

- Letters, or “epistles,” from war tax resisting Quakers to their fellow-Friends were an important way of spreading and maintaining the practice in the Society.

American war tax resistance can be said to have begun on , when John Woolman, Anthony Benezet, and several other Quakers addressed a letter in which they explained to other Friends why

David Cooper reflected on how thoughtful letters like these helped him maintain his war tax resistance in times of doubt:as we cannot be concerned in wars and fightings, so neither ought we to contribute thereto by paying the tax directed by the [recent] Act, though suffering be the consequence of our refusal, which we hope to be enabled to bear with patience.

Yearly Meetings would sometimes send letters to Quarterly or Monthly Meetings to reiterate the Quaker position on war tax resistance and give instructions as to how it should be enforced. For instance, this is from an letter from the North Carolina Yearly Meeting:I read with singular satisfaction the piece which you lent me respecting taxes, as it was very strengthening to my mind, which before was somewhat encompassed with weakness on this account.… I have since felt much weakness, and had come to no solid conclusion of mind, until I read your little manuscript, which caused my heart to rejoice, under a feeling sense that it is the truth which leads those who walk and abide in it to hold forth this testimony unto the world. And oh, says my soul, that I may yield faithful obedience to its monitions, let what will be the consequence.

…all our members should stand firm, and be faithful in bearing their testimony against war and military operations; taxes and fines appertaining thereunto, either directly or indirectly; or any way conniving or compromising with the specious and plausible offers of the legislature, by the tax proposed in the late act, to screen us from muster fines or military services. And in order that all our members may be clearly informed on this subject, and be fully prepared to meet the trial likely to come upon us by this law, we have thought it best to send it down in this epistle.

- American war tax resisters today do a lot of recruiting by reaching out to attendees of the annual protests of imperialist atrocities at the School of the Americas Watch vigils. Clare Hanrahan and Coleman Smith of NWTRCC carried the message of war tax resistance with them on a “circuit riding” barnstorm of activist centers in the American southeast. Harvard and Radcliffe activists used a petition drive to recruit phone tax resisters during the Vietnam War. And during that war also, individually-addressed letters were used to recruit new tax resisters to sign on to the “Writers and Editors War Tax Protest.”

- An organizer of the Dublin water charge strike recalls:

…months of work had been done in local areas convincing people of the primacy of [non-payment]. This was done through local public meetings, door-to-door leaflets and even knocking on doors and talking to people… The building of the campaign in this way was crucial. Local campaign groups were built and then came together and federated, rather than a central committee being formed first and then coming along to organise people.

…it became clear that while people might not have come out to the meeting, they had kept the information about the campaign and the campaign contact numbers had their place on a lot of fridge doors.

- American women’s suffrage activist Anna Howard Shaw wrote a letter to women in the movement in , urging them to refuse to fill out income tax returns. “In this manner we can show our loyalty to those who struggled to make this a free republic and who laid down their lives in defense of the equal rights of all free citizens to a voice in their own Government. … Let our protest be universal, and let every believer in justice unite in this mode of passive resistance and steadfastly refuse to assist the Government in its unjust and tyrannical violation of its fundamental principle that ‘taxation and representation are one and inseparable,’ and thus prove ourselves worthy descendants of noble ancestors, who counted no price too dear to pay in defense of liberty and equality and justice.” She told a reporter: “Since my letter was sent all over the country, I have received letters of encouragement and support from all directions,” and she soon thereafter won support for her stand from the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage.

- Only some of the women’s suffrage activists in Britain were responsible for paying taxes, so although tax resistance was an important part of the campaign there, it was a part not everybody could participate in. The movement made a special effort to find women who had taxes they could resist. For example, at one meeting in , Margaret Kineton Parkes “asked anyone present who knew women who paid taxes to send in their names, that they might be approached by her society.” In , Marie Lawson launched what she called a “snowball” protest: a sort of chain letter in which she sent out letters that advocated tax resistance (and protested on behalf of an imprisoned resister) and that asked the recipients to join her and to in turn send the same letter “to at least three friends.”

- The campaign to resist Thatcher’s Poll Tax used some creative outreach techniques (quotes from Danny Burns’s history of the movement):

- “The Aberdeen Anti-Poll Tax group was formed when people from the radical bookshop came together with a community arts group:

“…The local community arts group had a theatre group called “Wise Up” and they got a show together about the Poll Tax. They took this show around the estates with information for people about registration and how to fight it, to encourage them to set up local groups and support networks. The plays were performed in local community centres. Attendance for the plays varied from about 10 to 40 or more. The meetings which followed were encouraging because people gave their names as contacts or asked people to set up future meetings.”

- “In my local group… the union was built up through a door-to-door campaign. A group of five or six people (mostly friends) formed the core. They advertised a public meeting on the Poll Tax and about 50 people turned up. Out of these some joined the organising group. This small group then mass-produced a window poster which said ‘No Poll Tax Here.’ The poster was dropped through the letter-boxes of 2000 households and the group waited to see who put them up. Posters appeared in about 100 windows. Activists then went round and spoke to these people individually, inviting them to attend the next organising meeting; about fifteen did — enough to form the core of a group.”

- “[Our] network was strengthened by a door-to-door survey of over 500 households. The survey was not intended to be scientifically accurate. Its purpose was to give the APTU a fairly accurate picture of what was happening on the ground, and, perhaps more significantly, it was a pretext for engaging people in conversation about the Poll Tax, informing them of the non-payment campaign and encouraging them to join their local APTU.… Over a third of the people canvassed became paid up members of the union. By the end of the exercise Easton had over 300 members and street reps for almost every street. The canvass was not left there. The key to its success was the second visit. The group compiled all the statistics on a street by street basis and many of the reps then went back, door-to-door, and told people the results of the survey in their street and the neighbouring streets. A newsletter was delivered to everyone telling them what the overall results were for Easton. This meant that people knew how few of their neighbours were going to pay and it gave them confidence not to pay themselves. They had spoken to the canvassers personally, so they knew that the survey was genuine.”

- “An independent television company approached the Easton group in order to work with us on a film about the Poll Tax. The film was never shown, but the way the community was engaged in the process of making it is instructive. The film producers wanted a shot of all the doors in the street, opening one by one as the occupants came out of their houses with banners and signs. Charles, the local street rep, went round to people’s houses every evening for a week and explained to them what was wanted. Out of 30 houses in the street (a cul-de-sac) 28 agreed to participate. The street is multi-racial with a fairly wide class mix. It was inspiring to see white working class men standing shoulder to shoulder with Asian women and their kids, holding the same banners and engrossed in conversation. Some of them had never spoken to each other before. The film was made, but more importantly, as [a] result of making it, virtually every one of those households joined the Union, and most still had posters in their windows a year later. People were brought into the campaign, not through a leaflet or a canvasser, but through an interesting activity. They didn’t have to go to the campaign, it came to them.”

- “The Aberdeen Anti-Poll Tax group was formed when people from the radical bookshop came together with a community arts group:

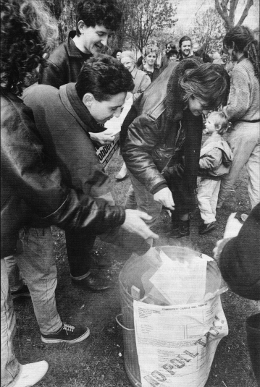

Public burnings of poll tax notices were good excuses for people to join in festive resistance activities.