Tax resisters frequently face the criticism of being freeloaders who enjoy the benefits of organized society without cooperating in the taxes necessary to fund them. This rhetorical attack paints the tax resisters as self-interested, anti-social tax evaders.

One way resisters have countered this attack is by staging flamboyant giveaways of their resisted taxes — both to make it clear that the resister does not have only selfish motives for resisting, and to demonstrate that the money is being spent for the benefit of society (and to a greater extent than if the money had been filtered through the government first).

Redirection is also a way of forging or strengthening ties with the recipient groups, and of making them aware of tax resistance as an option.

Today I will briefly describe some of the many examples of tax resisters and tax resistance campaigns that have used this technique, and the many variations they have come up with.

- Julia “Butterfly” Hill in redirected more than $150,000 of federal taxes that she owed that year, and made a point of saying “I ‘redirect’ my taxes rather than ‘resisting’ my taxes”:

I actually take the money that the IRS says goes to them and I give it to the places where our taxes should be going. And in my letter to the IRS I said: “I’m not refusing to pay my taxes. I’m actually paying them but I’m paying them where they belong because you refuse to do so.” They are not directing our money where it should be going, they are being horrific stewards of that money.

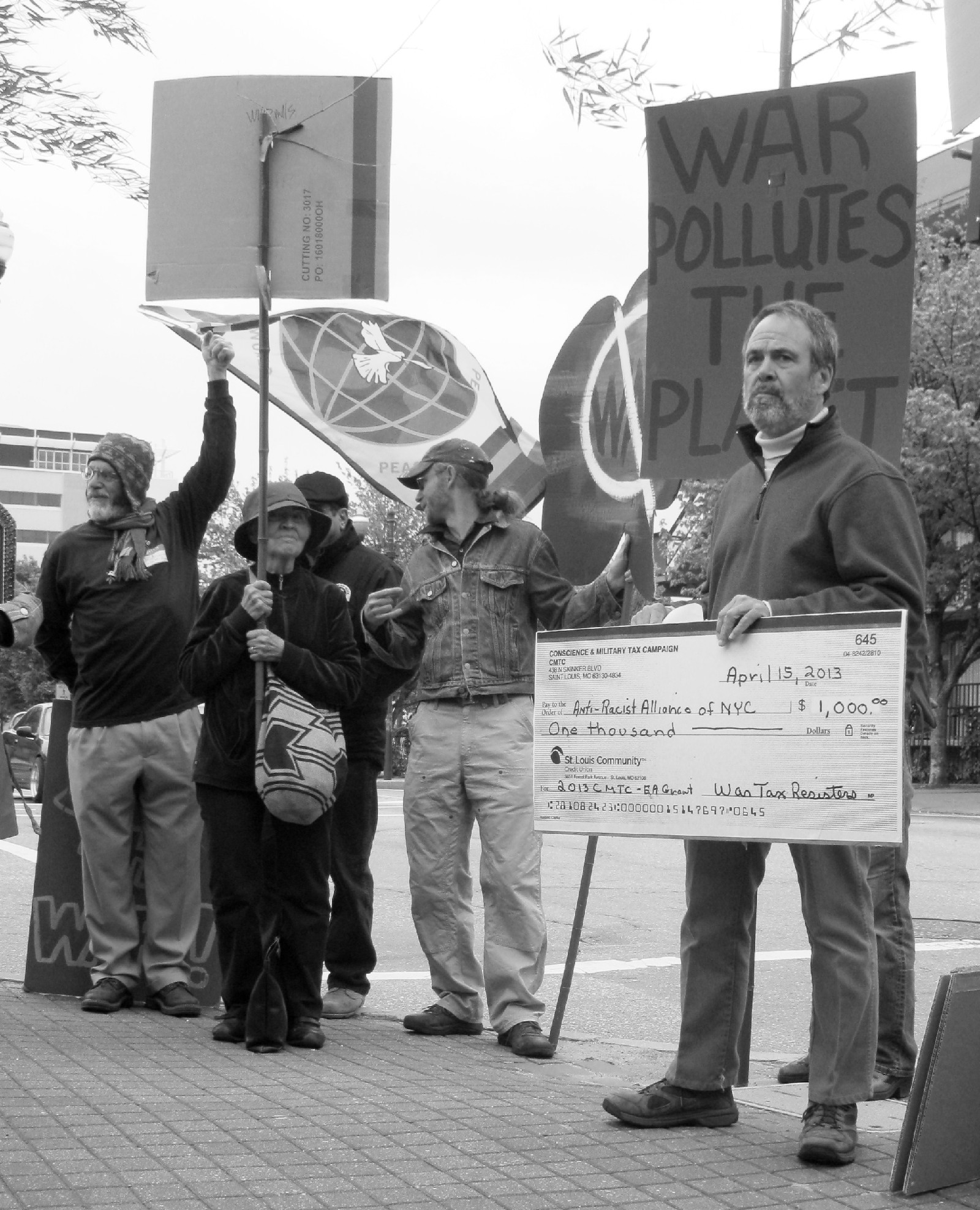

- NWTRCC organized what it called the “War Tax Boycott” in . It encouraged people to resist as a group, and as part of their resistance, to redirect any refused taxes to one of two groups: one that concentrated on providing health assistance in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, and the other that provides assistance for Iraq War refugees. The campaign kept track of how much money had been redirected over the course of the boycott, and then held a press conference at which oversized checks adding up to about $325,000 were given to spokespeople for these campaigns.

- The People’s Life Fund, associated with the group Northern California War Tax Resistance, accepts redirected taxes from resisters. If the IRS successfully seizes money from the resisters, the resisters can reclaim their donations to the Fund. Otherwise, the money remains there and earns interest and dividends. Every year the group pools these returns on investment and gives them away to local charitable organizations in a granting ceremony. Usually the grants are small — $500 or $1000 — but they give them to a dozen or more groups, which makes their granting ceremonies a good way for local charities to network with each other and for news of war tax resistance to spread in the local activist community. This same model, or one similar to it, is followed by a number of regional redirection funds associated with war tax resistance groups.

- A family in Vermont figured out a way to get extra mileage out of their redirection: “They refused to pay 50% of their tax liability and redirected it to Plan International’s Childreach program. Childreach has a fund drive for a project to help children in Nepal and Ghana, and has received a challenge grant from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). This means that the $211.69 that the WTR family has redirected will result in a $423.38 matching contribution from the U.S. government!”

- In , several hundred Spanish war tax resisters redirected over €85,000 to the group “La’Onf,” which was organizing and educating about nonviolent conflict resolution techniques in Iraq.

- The Mennonite Central Committee has established a “turning toward peace” fund especially designed for people who want to redirect their tax dollars from the government to more constructive projects — for example, education for children in Afghanistan.

- War tax resisters Paul and Addie Snyder made a point of saying “we believe in paying taxes” as they explained in that they wouldn’t be paying those taxes to the federal government, but instead would be giving the money directly to rural poverty projects nearby.

- In several hundred American Quaker war tax resisters paid their tax dollars to a Catholic soup kitchen in Philadelphia.

- The Women’s Tax Resistance League largely suspended its campaign during World War Ⅰ, but one woman, writing as “A Persistent Tax Resister” wrote a letter to the editor of a suffragist paper suggesting that women “should contribute the sum she owes to the Government to a National Fund of her own choosing, and should send her donation as ‘Taxes withheld from the Government by a voteless woman.’ ” Charlotte Despard, for example, “said she had offered to give voluntarily the amount demanded of her by Revenue authorities to any war charity, but her offer had not been accepted.”

- A war tax resistance group in Iowa used the proceeds from their redirection fund to create a scholarship for college students who would be ineligible for government financial aid because of refusal to register for the draft. Another, in Pennsylvania, made an interest-free loan to a defense committee that was supporting a group of draft resisters who were on trial.

- In , 70 war tax resisters went to the phone company offices in Boston to pay their bills minus the federal excise tax. They then collected this refused tax ($142 worth) by passing an army helmet around, and donated it to the United Farm Workers to help them set up a clinic in California. Also , the Cornell branch of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam did a similar phone company office protest and collection of redirected phone taxes, donating the money to a local Early Childhood Development program.

- In , war tax resister Irving Hogan stood outside the Federal Building in San Francisco and redirected his federal income tax dollars one at a time — by handing them out to passers by. “I want this money to be used for the delight, not the destruction, of men,” he said. “Here: go buy yourself a beer.”

- John and Pat Schwiebert did something similar: “One year they converted their war tax debt into five-dollar bills, which they gave to individuals waiting in line at the city unemployment office. They included a letter with each donation telling why they were doing this, and they notified media beforehand. Their actions garnered them an interview on NPR, and they received letters and cards from around the world.”

- In a group of war tax resisters in New York redirected their war taxes as nickels that they handed out to people waiting at the bus stops on lines where fare hikes were being proposed, saying “this is where our tax dollars should be going.”

And here’s something kind of similar that doesn’t fit into any of my other categories, so I’ll toss it in here:

- When the IRS seized back taxes from war tax resister Mary Regan’s retirement account in , she threw a fundraising party to try to raise an equivalent amount of money — not to reimburse her, but to give away to charities like “the Boston Women’s Fund, the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Friends Service Committee, a homeless shelter for youth, and the peace movement in Israel.”