I’ve jumped the gun in posting ’s entry, as I’ll be off the grid for a few days. Please excuse the anachronism. But, then again, when I’m posting about something that happened , I’m not likely to be violating any press embargo.

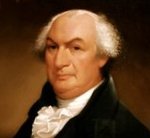

Gouverneur Morris, among other things one of the major authors of the United States Constitution, was very critical of the United States’ pursuit of the War of .

On , he wrote a defense of war tax resistance that extends the Quaker argument against providing funding for war in general into an argument for withholding funding from specific, unjust wars:

Now let our case be stated as it stands on our principles, and on those of our opponents. And, first, let the place of honor be given to them. They insist, that the war is just and necessary, yet they refuse to support it by taxes. Contending, nevertheless, that their war is just, they infer the justice of the debt incurred, and conclude that we, who opposed it, are bound to do what they who declared it would not do; that we must impose taxes to defray the expense. Permit me here to ask, whether the worthy eight per cent patriots, who are about to lend, rely on these honest non-taxing gentlemen for payment. If they do, and are not deceived, we must submit, and contribute in spite of our teeth, should the union endure. But, according to my old-fashioned way of reasoning, founded on the vulgar notions, that lambs cannot eat foxes, nor pigeons catch hawks, these honest gentlemen will not impose taxes, and of course those worthy patriots, consoling themselves with the honor of their deed, must forego the profit, unless we step in to their aid. Must we, then, for the sake of such excellent patriots, lay heavy direct taxes to pay usurious interest on enormous sums, extravagantly squandered in the prosecution of what we consider an unjust war?

To ask what is war, may seem a strange question, and yet every one should put it to himself on the present occasion. War is that condition, in which men are called on to take away the lives of their fellow-creatures. There are many, who religiously believe such condition to be unjustifiable under every possible circumstance. There are some, who act on the principle, that ambition or cupidity will justify any war, a principle, which is, I trust, confined to the bosoms of a very few very bad men. Those, who consider themselves as moral agents accountable to God, hold it impious to support an unjust war, and so it is held by the writers on public law. I never heard it questioned, much less denied, that the people called Quakers act consistently with their principles, when, refusing to pay war taxes, they suffer public officers to levy the money by sale of their property. Admitting, however, for argument’s sake, that in so doing they carry the matter too far, surely it will not be pretended, that they could, with any regard to consistency of character or conduct, lay such taxes on themselves and others. But in what does our present case differ from theirs? We hold this war in the same abhorrence, which they do every war, and the only question is, whether we may do that indirectly which we ought not to do directly. You may still, in defense of your post, insist that we are bound to pay public debts by the same moral principle, which bids us pay our private debts. Agreed. But we are bound to pay only just debts; or, to speak more accurately, that is no debt which was not justly contracted. To resume the common mode of speech, can that be a just debt, which is contracted for the support of an unjust war? You will answer, perhaps, that he who lends his money is not accountable for the use made of it by the borrower. But how, if the borrower had apprized him of the use? Suppose, for instance, money lent for the express purpose of hiring a bravo to commit murder; would you, as executor of the borrower, hold yourself bound to pay it? I should like to hear so worthy a lender make his demand. He perhaps would feel bashful, and, having with the caution usual in such business, taken a note payable to the bearer, would send a third person. I believe you would tell such person, that no binding contract can be founded on crime, and that the transfer of an unjust demand cannot convert it into a debt.

Unwilling to give the matter up, you may perhaps take a wider range, and ask whether this principle would not operate injuriously, by depriving the government of pecuniary resource, when engaged hereafter in a war not only just but unavoidable. To this I reply, in the language of Holy Writ, “you shall not do evil that good may come of it.” I am moreover persuaded, that the best mode of securing pecuniary aid for a just purpose, is to withhold payment of what has been advanced for an object manifestly unjust.

It would lead too far, besides leading us astray, to develop the ground of this opinion. I conclude, therefore, shortly thus. An agent, though he comply with legal forms, cannot bind his principal to a matter, which is illegal or immoral; and a third person cannot ground a legal claim on such transaction, if he were privy to the wrong. The debt, therefore, now contracting by Messrs Madison and Company is void, being founded in moral wrong, of which the lenders were well apprised. Should they hereafter plead ignorance, let them be told it was a vincible, and therefore an inexcusable ignorance.

This work can also be found in the book American Quaker War Tax Resistance.