On , on the thirty-ninth anniversary gathering of the Universal Peace Union, the group met in Mystic, Connecticut. Mystic was also, not coincidentally, the birthplace of the Rogerene (or “Rogerene Quaker”) sect of Christian pacifists which included war tax resisters. Towards the end of , the president, Alfred H. Love,

…spoke of Zerah C. Whipple, who was taken from that platform and imprisoned because of his refusal to pay war tax. A boy born about that time was named for him, and being now present he called upon him for a recitation. So Zerah C. Whipple Crouch gave “When the War Drums Cease Their Beating.” As he left the platform, Mr. Love said to him, “Be as good as you speak, and speak as good as you are.”

Today I’ll try to dig up some more information about Zerah Colburn Whipple.

Zerah C. Whipple (–)

The story of his tax resistance is told briefly in Anna B. Williams’s The Rogerenes: Some Hitherto Unpublished Annals Belonging to the Colonial History of Connecticut (, pages 315–6):

In , James E. Whipple, of Quakertown, a young man of high moral character, having refused from conscientious scruples to pay the military tax imposed upon him, was arrested by the town authorities of Ledyard and confined in the Norwich jail, where he remained several weeks.

About the same time, Zerah C. Whipple, being called upon to pay a military tax, refused to thus assist in upholding a system which he believed to be anti-Christian and a relic of barbarous ages. He was threatened with imprisonment; but some kindly disposed person, interfering without his knowledge, paid the tax.

In a petition, signed by members of the Peace Society, was presented to the legislature of Connecticut praying that body to make such changes in the laws of the State as should be necessary to secure the petitioners in the exercise of their conscientious convictions in this regard. The petition was not granted; but the subject excited no little interest and sympathy among some of the legislators.

In the summer of , Zerah C. Whipple, still refusing to do what his conscience forbade, was taken from his home by the tax collector of Ledyard and placed in the New London jail. His arrest produced a profound impression, he being widely known as the principal of the school for teaching the dumb to speak, and also as a very honest, high-souled man.

During his six weeks’ imprisonment, the young man appealed to the prisoners to reform their modes of life, reproved them for vulgarity and profanity, furnished them books to read, and began teaching English to a Portuguese confined there. The jailer himself said, to the commissioner, that although he regretted Mr. Whipple’s confinement in jail on his own account, he should be sorry to have him leave, as the men had been more quiet and easy to manage since he had been with them. On the evening of the sixth day, an entire stranger called at the jail and desired to know the amount of the tax and costs, which he paid, saying he knew the worth of Mr. Whipple, that his family for generations back had never paid the military tax, and he wished to save the State the disgrace of imprisoning a person guilty of no crime. This man was not a member of the Peace Society. Mr. Whipple afterwards learned that his arrest was illegal, the laws of the State providing that where property is tendered, or can be found, the person shall be unmolested. The authorities of Groton did not compel the payment of this tax by persons conscientiously opposed to it.

In , The Bond of Peace [the newsletter of the Connecticut Peace Society, founded by Jonathan Whipple, Zerah’s grandfather] was removed to Quakertown and its name changed to The Voice of Peace. Zerah C. Whipple undertook its publication and continued it until , when it was transferred to a committee of The Universal Peace Union. It is now published in Philadelphia as the official organ of that Society, under the title of The Peacemaker.

An edition of The British Friend adds some details, and explains the “who was taken from that platform eighteen years ago” aside in the first passage I quoted:

A Recent Imprisonment in Connecticut.

The State of Connecticut has recently afforded an example of her practical disregard for the rights of conscience, by the imprisonment of an excellent Christian citizen of prominent philanthropy, for the non-payment of a militia-tax, during a time of profound peace, and this, too, whilst America ostentatiously boasts that she only needs a standing army of some 20,000 men. There resides at Mystic, in Connecticut, a gentleman named Zerah C. Whipple, whose ancestors for five generations have been members of the Society of Friends. Neither he, nor his father, nor his grandfather, have ever paid any military tax specially levied as such. He has obtained considerable celebrity in the States as a successful educator of the dumb, and is at the head of an institution for the care of persons thus afflicted with the privation of speech. For the non-payment of a militia-tax, he was recently taken from his home, and thrust into one of those low gaols which abound throughout America, and where the vilest of criminals are herded promiscuously together. Z.C. Whipple was placed in a large room with a number of common felons.

At a meeting of the Friends of Peace, held in the neighbourhood of the prison, much indignation was expressed at his treatment, and the dishonour thereby done to the State. One speaker, J.H.K. Wilcox, very justifiably exclaimed:— “Is this the average conscience of Connecticut? If so, I think it is time we throw off the delusion that America is the freest country in the world. Instead of feeling proud, we should lay our faces in the dust, because there is so much difference between our practice and our profession.” A curious incident occurred at the meeting, as exemplifying a custom of United States gaolers. But we must quote from the American report itself:— “An offer had been made by an officer to bring the prisoner to the meeting, provided that he could receive ten dollars; the money had been placed in the hands of a party, to be given to the officer when he brought him here. The officer had not gone a great while before Z.C. Whipple came walking into the meeting.” He then received the hearty congratulations of his assembled friends, and delivered a speech, after which he returned to prison. The Philadelphia Voice of Peace thus describes the mode of Z.C. Whipple’s liberation:— “At an unexpected moment an entire stranger called at the prison and desired to know the amount of the tax and costs, which he paid, saying he knew the worth of Z.C. Whipple, and that his family for generations back had never paid the military tax, and he wished to save the State from the disgrace of imprisoning a person guilty of no crime. The money was paid and the door opened, and his friend took the receipt to his children and said, ‘Keep this as a reminiscence that in your father paid this bill to release a young man from prison, that he might enjoy the rights of conscience.’ This man was not a member of the Peace Society.” If Connecticut continues thus to make “progress” backward, who knows what we may ultimately hear of? New England once distinguished herself by hanging Quakers and imprisoning Baptists and Independents for conscience’ sake. She has already returned to imprisoning; and it is not such a very long way further to fill up the remainder of the programme once more. But such modes of procedure are specimens of “freedom” which Englishmen may thankfully rejoice they do not witness at home.

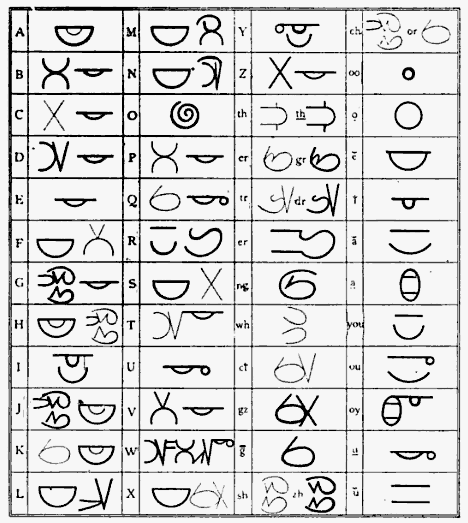

Whipple was well-known for his work with the deaf, which was inspired by his grandfather’s patiently teaching his deaf son (Zerah’s uncle) to speak and lip-read proficiently. Zerah’s method emphasized lip-reading and learning to speak by using tactile and visible feedback, something he called the “Pure Oral Method” to distinguish it from attempts to teach sign language to the deaf, which he felt ghettoized their communication. He also developed a phonetic alphabet to use in his instruction in which the letters were schematic representations of the position of the vocal organs when pronouncing the sound. His school still exists, now as the “Mystic Educational Center.”

Whipple’s phonetic alphabet

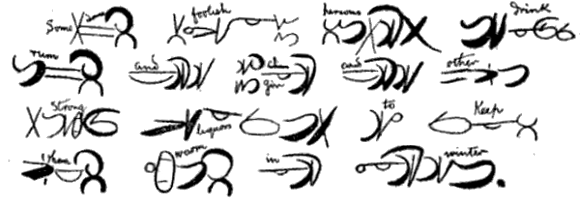

From a homework assignment: “Some foolish persons drink rum and gin and other strong liquors to keep them warm in Winter.”

In , Whipple unsuccessfully petitioned U.S. president Grant to commute the death sentences of prisoners captured in The Modoc War.