Disrupt Tax Auctions

If the government succeeds in seizing property from tax resisters, a tax resistance campaign may still prevent the government from selling the stolen goods. Disrupting auctions (or using them as occasions for demonstrations) has been a popular tactic.

Example Religious Nonconformists in the U.K.

Section titled “ Religious Nonconformists in the U.K.”Tithe resisters and other religiously nonconformist tax resisters in the U.K. frequently disrupted auctions. Here is one jaunty summary from an American newspaper:

The non-conformists in the English town of Coventry refuse to pay tithes and all the country round is having a good deal of fun over it. The bailiffs attempted to levy on the pigs of a farmer who refused to pay, but the farmer had carefully lathered the porkers with grease and the bailiffs gave it up. A Birmingham auctioneer tried to sell some goods that had been seized but he no sooner opened his mouth to announce the sale when an ancient egg cracked over his teeth and a cabbage hit him on the nose. The auctioneer immediately retired to Birmingham. There is great excitement and the police hesitate to answer the demands of the tithe collectors for assistance fearing a riot if they interfere.

Example Education Act-related Resistance

Section titled “ Education Act-related Resistance”Some auction disruption took place during the tax resistance campaign against the provisions of the Education Act of 1902 that provided taxpayer money for sectarian education. One resister named his sheep after offensive politicians so as to turn their auction into an occasion for political commentary:

Difficulty is experienced everywhere in getting auctioneers to sell the property confiscated. In Leominster, a ram and some ewe lambs, the property of a resistant named Charles Grundy, were seized and put up at auction, as follows: Ram, Joe Chamberlain; ewes, Lady Balfour, Mrs. Bishop, Lady Cecil, Mrs. Canterbury, and so on through the list of those who made themselves conspicuous in forcing the bill through Parliament. The auctioneer was entitled to a fee under the law of 10 shillings and 6 pence, which he promptly turned over to Mr. Grundy, having during the sale expressed the strongest sympathy for the tax-resisters. Most of the auction sales are converted into political meetings in which the tax and those responsible for it are roundly denounced.

Example Edinburgh Annuity Tax Resistance

Section titled “ Edinburgh Annuity Tax Resistance”Auction disruptions were commonplace in the Annuity Tax resistance campaign in Edinburgh. By law the distraint auctions (“roupings”) had to be held either at the homes of the resisters or at the Mercat Cross—the town square, essentially. Either way this made it easy to gather a crowd:

[I]magine… an unfortunate auctioneer arriving at the Cross about noon, with a cart loaded with furniture for sale. Latterly the passive hubbub rose as if by magic. Bells sounded, bagpipes brayed, the Fiery Cross passed down the closses, and through the High Street and Cowgate; and men, women, and children, rushed from all points towards the scene of Passive Resistance… Respectable shopkeepers might be seen coming in haste from the Bridges; Irish traders flew from St. Mary’s Wynd; brokers from the Cowgate; all pressing round the miserable auctioneer; yelling, hooting, perhaps cursing, certainly saying anything but what was affectionate or respectful of the clergy. And here were the black placards tossing above the heads of the angry multitude—

ROUPING FOR STIPEND!

This notice was of itself enough to deter any one from purchasing… The people lodged the placards and flags in shops about the Cross, so that not a moment was lost in having their machinery in full operation, and scouts were ever ready to spread the intelligence if any symptoms of a sale were discovered.

It was difficult for the authorities to get any help, either from auctioneers, furniture dealers, or carters. The government had to purchase (and fortify) their own cart because they were unable to rent one for such use.

One witness testified about a disrupted auction that was held at a resister’s home:

I saw a large number of the most respectable citizens assembled in the house, and a large number outside awaiting the arrival of the officers who came in a cab, and the indignation was very strong when they got into the house, so much so that a feeling was entertained by some that there was danger to the life of Mr. Whitten, the auctioneer, and that he might be thrown out of the window, because there were such threats, but others soothed down the feeling.…

Q: Did Mr. Whitten, from his experience on that occasion, refuse ever to come to another sale as auctioneer?

A: He refused to act again, he gave up his position.

On another occasion, the auction seemed to go smoothly at first, but the buyers didn’t get what they hoped for:

At Mr. McLaren’s sale everything was conducted in an orderly way as far as the sale was concerned. We got in, and only a limited number were allowed to go in; but after the officials and the police had gone, there was a certain amount of disturbance. Certain goods were knocked down [sold] to the poinding creditors, consisting of an old sofa and an old sideboard, and Mr. McLaren said, “Let those things go to the clergy.” Those were the only things which had to be taken away. There was no vehicle ready to carry them away. Mr. McLaren said that he would not keep them. After the police departed, he turned them out in the street, when they were taken possession of by the crowd of idlers, and made a bonfire of.

A summary of the effect of all of this disruption reads:

So strong was the feeling of hostility, that the town council were unable to procure the services of any auctioneer… and they were consequently forced to make a special arrangement with a sheriff’s officer, by which, to induce him to undertake the disagreeable task, they provided him for two years with an auctioneer’s license from the police funds. In March 1865, it was found necessary to enter into another arrangement with the officer, by which the council had to pay him 12½ percent, on all arrears, including the police, prison, and registration rates, as well as the clerical tax; and he receives this percentage whether the sums are recovered by himself or paid direct to the police collector, and that over and above all the expenses he recovers from the recusants. But this is not all; the council were unable to hire a cart or vehicle from any of the citizens, and it was found necessary to purchase a lorry, and to provide all the necessary apparatus and assistance for enforcing payment of the arrears. All this machinery, which owes its existence entirely to the Clerico-Police Act, involves a wasteful expenditure of city funds, induces a chronic state of irritation in the minds of the citizens, and is felt to be a gross violation of the principles of civil and religious liberty.

Example The Tithe War

Section titled “ The Tithe War”William John Fitzpatrick wrote of the auctions during the Tithe War in Ireland:

[T]he parson’s first step was to put the cattle up to auction in the presence of a regiment of English soldiery; but it almost invariably happened that either the assembled spectators were afraid to bid, lest they should incur the vengeance of the peasantry, or else they stammered out such a low offer, that, when knocked down, the expenses of the sale would be found to exceed it. The same observation applies to the crops. Not one man in a hundred had the hardihood to declare himself the purchaser. Sometimes the parson… would order the cattle twelve or twenty miles away in order to their being a second time put up for auction. But the locomotive progress of the beasts was always closely tracked, and means were taken to prevent either driver or beast receiving shelter or sustenance throughout the march.

The Sentinel wrote of one auction:

Yesterday being the day on which the sheriff announced that, if no bidders could be obtained for the cattle, he would have the property returned to Mr. Germain, immense crowds were collected from the neighbouring counties—upwards of 20,000 men. The County Kildare men, amounting to about 7,000, entered… in the most regular and orderly manner. This body was preceded by a band of music, and had several banners on which were “Kilkea and Moone, Independence for ever,” “No Church Tax,” “No Tithe,” “Liberty,” etc… The cattle were ordered out, when the sheriff, as on the former day, put them up for sale; but no one could be found to bid for the cattle, upon which he announced his intention of returning them to Mr. Germain. The news was instantly conveyed, like electricity, throughout the entire meeting, when the huzzas of the people surpassed anything we ever witnessed. The cattle were instantly liberated and given up to Mr. Germain.… Thus terminated this extraordinary contest between the Church and the people, the latter having obtained, by their steadiness, a complete victory. The cattle will be given to the poor of the sundry districts.

Similar scenes were reported elsewhere:

Some cows seized for tithes were brought to a public place for sale, escorted by a squadron of lancers, and followed by thousands of infuriated people. All the garrison, cavalry and infantry, under the command of Sir George Bingham, were called out. The cattle were set up at three pounds for each, no bidder; two pounds, no bidder; one pound, no bidder; in short, the auctioneer descended to three shillings for each cow, but no purchaser appeared. This scene lasted for above an hour, when there being no chance of making sale of the cattle, it was proposed to adjourn the auction; but, as we are informed, the General in command of the military expressed an unwillingness to have the troops subjected to a repetition of the harassing duty thus imposed on them. After a short delay, it was, at the interference and remonstrance of several gentlemen, both of town and country, agreed upon that the cattle should be given up to the people, subject to certain private arrangements. We never witnessed such a scene; thousands of country people jumping with exulted feelings at the result, wielding their shillelaghs, and exhibiting all the other symptoms of exuberant joy characteristic of the buoyancy of Irish feeling.

At Carlow… Some cattle had been seized for tithe, and a public sale announced, when a large body of men, stated at 50,000, marched to the place appointed, and, of course, under the influence of such terror, none were found to bid for the cattle. The sale was adjourned from day to day, for seven days, and upon each day the same organised bands entered the town, and rendered the attempt to sell the cattle, in pursuance of the law, abortive. At last the cattle are given up to the mob, crowned with laurels, and driven home with an escort of 10,000 men.

Example Tithe Riots in Wales

Section titled “ Tithe Riots in Wales”Similar actions took place in Wales as part of the later tithe resistance there. One report reads:

On Saturday last, a body of bailiffs acting on behalf of the owners of the tithe rent-charge, and accompanied by an auctioneer, Mr. Roberts, and an appraiser, attempted to sell the cattle of certain farmers previously seized under a distraint… News of the intended sale, however, had reached the valley by 4 o’clock in the morning. The means taken to summon the neighbouring farmers and their labourers to resist the seizure and sale were as picturesque as the gathering-signal of a Highland clan. From twelve anvils cannons were fired, and at the doors of thirty farmhouses immense horns 6 ft. long were blown by the farmers’ wives. On the mountain-path… was raised a long pole, with a faggot saturated with paraffin attached to its top. This beacon set ablaze soon summoned from their homes nearly a thousand persons, armed with stout cudgels. When the auctioneer and his assistants drove upon the scene, their way was blocked by this crowd. On their attempting to force a road through, the rioters clubbed the horses on the face. The frightened animals rushed forward, smashing the carriage, so that a piece of the shaft entered the body of one of them, and then dashed through the crowd and down the road at a furious pace. Some constables who were accompanying the bailiffs were flung out, but the auctioneer and his assistant clung to their seats. The crowd followed the flying carriage, and since the horses soon fell, exhausted from loss of blood, overtook it about a mile off. An extraordinary scene seems to have ensued. The crowd, drunk with rage and excitement, surrounded the unfortunate men, and seemed about to give way to some sudden access of tumultuary fury. It appeared as if nothing could save the two men from being torn in pieces. They were preserved, however, by one of those sudden revulsions of feeling in the mob such as we read of in the tumults of the French Revolution. Two of the farmers under distraint, Mr. Jones and Mr. Thomas Thomas, with a courage and heroism that do them the highest honour, seized Roberts and his assistant, and declared that they would die with them. This act seems at once to have taken effect on the crowd, and they desisted from their furious attack. They were not, however, content to let the men go till the auctioneer had gone down upon his knees in the road, and sworn a solemn oath never again to enter the district, or to assist in the collection of tithes. This oath was extorted from the appraiser also; the coats of both men were then taken off and turned, and in this condition they were marched along at the head of the crowd, a red flag being borne in front of them and a black one behind.

Example Tithe Resistance in England

Section titled “ Tithe Resistance in England”England wasn’t far behind in the resistance, and the tactics the resisters used were various. A 1931 newspaper article says:

[T]hey have made conditions very unhappy for auctioneers selling property for non-payment of tithes.

They have stampeded oxen so that the sale of them could not continue. They have browbeaten bidders so that prices adequate to pay the tithes have not been reached; they have stoned auctioneers, thrown them in ponds, plastered them with mud, slashed their tires, and organized mass resistance to tithe collecting in other ways.

Another reports:

Whenever a seizure was threatened, farmers and their workers from all around appeared on the scene, armed with sticks, pitchforks, and spades. In some cases barricades were thrown up, trenches were dug across approaches to the farms, gates were buttressed with tree trunks, and barbed wire fences put up.

Tithe owners who seek to foreclose come to grief. When cattle or farm implements are put up for sale, the farmer’s friends bid the articles in for a song. Not many outsiders have dared come to make a higher bid. At times standing crops of grain have been offered for sale. These sales, too, have been mainly failures, because prospective outside bidders found they could not secure in the neighborhood laborers who would cut the grain, nor machines with which to do the work.

And another:

Acting on a distraint warrant, Mr. A. Saunders, court bailiff, offered the goods for sale to meet a sum of £7 11/9 due in respect of tithe and costs. For the whole of the contents of the house, excluding wearing apparel and bedding, only £1 10/6 was realised. Neighboring farmers made bids of 1/ or so—the highest was 7/6—and as no further offers were forthcoming the lots were knocked down at these farcical figures.

And another:

Two hundred angry East Kent farmers poured a bucket of mud over the head of an auctioneer during a Canterbury sale to recover arrears of tithe rent against which farmers everywhere are rebelling. They stoned his police guard, and the sale was abandoned, the auctioneer escaping in a police car.

Another sale at Hastings was wrecked, the farmers stampeding bullocks put up for sale.

And another:

When the sale started… a total stranger bid £5, then £10, and the crowd surged forward with cries of “Who is this man?”… The stranger was thereupon attacked, and in spite of police protection, was heavily stoned, and mud and refuse were flung at him as he was hustled and jostled off the premises. The tyres of his car were punctured, and he narrowly escaped a ducking in the pond. He drove away amid a hail of stones and mud.

And another:

Hilarious scenes occurred at a tithe sale… when two bullocks were offered for auction in respect of a tithe debt of 30/. About 200 farmers gathered, and a strong contingent of police were in attendance. Bidding started at 1/, but there were genuine buyers present, and amid hostile cries the price rose to £3. Then there came a chorus of simultaneous bids from farmers of £20. “Who made that bid?” demanded the auctioneer, and again met with a chorus of claimants. He had no recourse but to restart the sale. This happened a dozen times, and on one occasion, when the figure reached £5000, the successful bidder confessed he had only 8d., and the sale began again. The bullocks stood peacefully in the ring until the farmers tired of their entertainment; then a concerted attack with sticks was made on the bullocks, which dashed from the ring, scattering bidders, auctioneer, and police, and vanished over the distant marshes pursued by the police. The sale was then announced to be off.

And another:

One day an auctioneer attempted to sell 10 cows belonging to… an alleged tithe defaulter, but on arrival he found that the animals had been mixed with about 70 others. Amid much confusion he announced that the sale could not take place.

And another:

Seventeen out of 18 pigs on a Suffolk (England) farm which were seized for tithe arrears died mysteriously. A tender of £18 for the animals had been accepted when two of them died, and an order under the swine fever regulations prevented the removal of the rest. Of these 15 then died, so a post-mortem examination was made by a Ministry of Agriculture inspector. This revealed that all the 17 pigs had died from prussic acid poisoning.

Example Poor Rates Rebellion in Waterford

Section titled “ Poor Rates Rebellion in Waterford”Opposition to the “poor laws” in Britain sometimes took the form of refusal to pay “poor rates.” In County Waterford, Ireland, resisters successfully prevented the sale of their property for tax arrears.

[A] mob consisting of at least from 5 to 6,000 men entered Waterford, every one of whom appeared armed with bludgeons, of immense size, one or two had pikes, and as they proceeded through the city they alarmed the peaceful inhabitants by the most savage yells, accompanied by the flourishing demonstration of their clan-alpeens…

As a consequence:

Mr. Robert Fleming, the poor rate collector… has, in consequence of the organized system of opposition and passive resistance given by the farmers in Gaultier… abandoned the idea of distraining, for he could get no one to buy the goods seized.

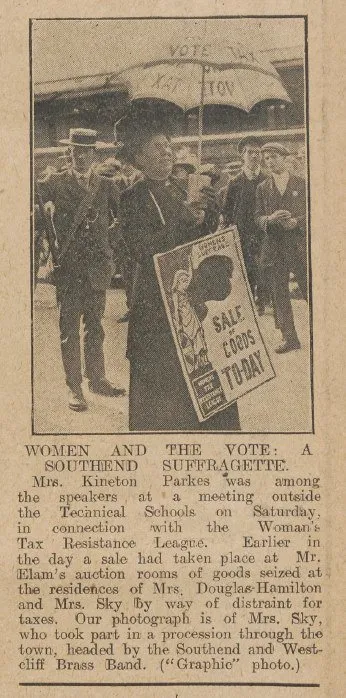

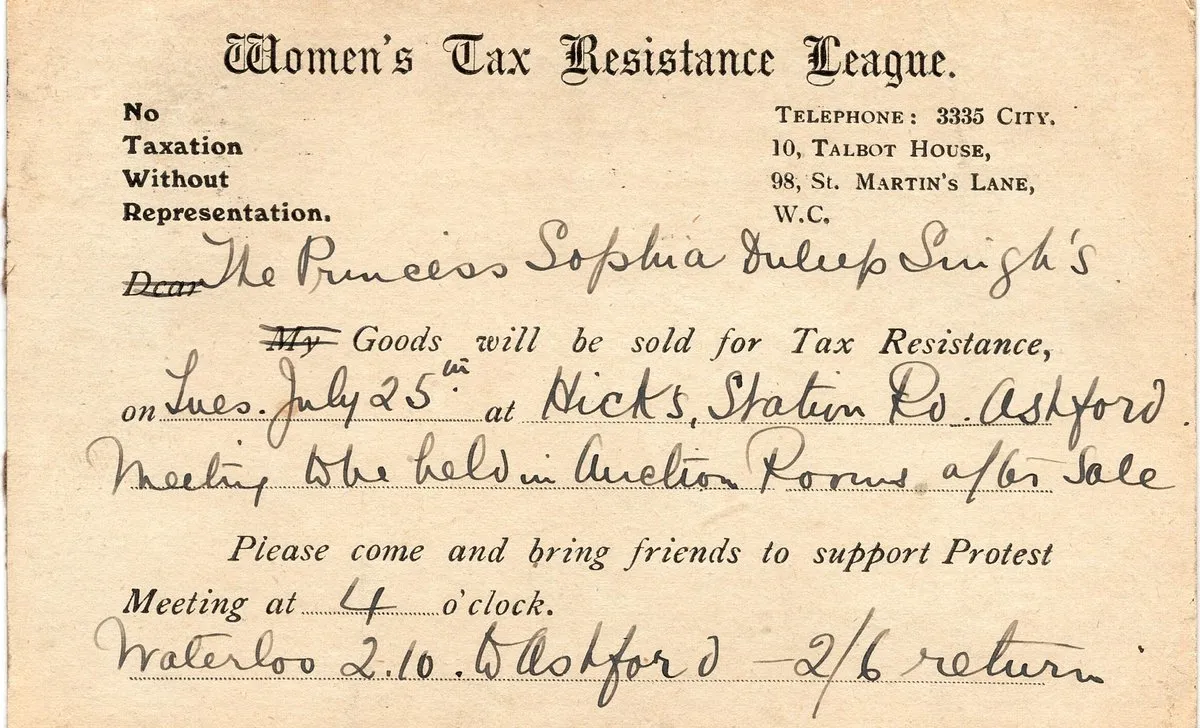

Example The British Women’s Suffrage Movement

Section titled “ The British Women’s Suffrage Movement”Tax resisters in the women’s suffrage movement in the U.K. were particularly adept at disrupting tax auctions and making them opportunities for propaganda and protest.

Practically every day sees a sale and protest somewhere, and the banners of the Women’s Tax Resistance League, frequently supported by Suffrage Societies, are becoming familiar in town and country. At the protest meetings which follow all sales the reason why is explained to large numbers of people who would not attend a suffrage meeting. Auctioneers are becoming sympathetic even so far as to speak in support of the women’s protest against a law which demands their money, but gives them no voice in the way in which it is spent.

Sometimes sympathetic auctioneers allowed activists to address bidders before the auction began. In this way, the auctions spread the suffragist message to new audiences. Indeed, suffragists would often walk through town with sandwich-boards, banners, and leaflets—simultaneously advertising and protesting the auction to try to draw a crowd.

At one auction, a suffrage activist called out for “three cheers” for the tax resister whose goods had been auctioned off. “The hearty response from the men… came as a surprise to the Suffragists themselves.”

On another occasion, the gathering came to resemble a suffrage rally more than an auction:

The sale was conducted, laughably enough, under the auspices of the Women’s Freedom League and the Women’s Tax Resistance League… The rostrum was spread with our flag proclaiming the inauguration of Tax Resistance by the W.F.L.; above the auctioneer’s head hung Mrs. Despard’s embroidered silk banner, with its challenge “Dare to be Free”; on every side the green, white and gold of the W.F.L. was accompanied by the brown and black of the Women’s Tax Resistance League, with its cheery “No Vote, no Tax” injunctions and its John Hampden maxims…

Sometimes these protests convinced the assembled bidders to refuse to bid on the stolen goods:

Miss Andrews asked the auctioneer if she might explain the reason for the sale of the waggon, and, having received the necessary permission was able to give an address on tax resistance, and to show how it is one of the weapons employed by the Freedom League to secure the enfranchisement of women. Then came the sale—but beforehand the auctioneer said he had not been aware he was to sell “distressed” goods, and he very much objected to doing so.… The meeting and the auctioneer together made the assembly chary of bidding, and the waggon was not sold, which was a great triumph for the tax-resisters.

A less-sympathetic auctioneer might refuse to allow the activists to address the crowd from the rostrum, only to regret this decision when the activists instead shouted him down from the crowd or from the street outside.

When the government seized the goods of tax resisters and auctioned them off, this overt attack tended to unify the opposition and make it overlook its own differences of opinion. One suffragist noticed this about an auction protest:

Certainly the most striking feature of this protest was the fact that members of all societies in Hastings, St. Leonards, Bexhill, and Winchelsea united in their effort to render the protest representative of all shades of Suffrage opinion. Flags, banners, pennons, and regalia of many societies were seen in the procession.

The government once peevishly seized about £80 worth of household goods from a woman who had resisted only about £15 in taxes:

[I]t was at once decided by the Women’s Tax Resistance League and Mrs. Tollemache’s friends that such conduct on the part of the authorities must be circumvented and exposed. The goods were on view the morning of the sale, and as there was much valuable old china, silver, and furniture, the dealers were early on the spot, and buzzing like flies around the articles they greatly desired to possess. The first two pieces put up were, fortunately, quite inviting; £19 being bid for a chest of drawers worth about 50s. and £3 for an ordinary leather-top table, the requisite amount was realised, and the auctioneer was obliged to withdraw the remaining lots, much to the disgust of the assembled dealers. Mrs. Kineton Parkes, in her speech at the protest meeting, which followed the sale, explained to these irate gentlemen that women never took such steps unless compelled to do so, and that if the tax collector had seized a legitimate amount of goods to satisfy his claim, Mrs. Tollemache would willingly have allowed them to go.”

The government tried to sell suffragist tax resister Kate Harvey’s property from within her home rather than from a public auction house, thinking that this might make protest more difficult. That turned out to be a miscalculation. A group of suffragist men drew a crowd by carrying placards through the town that read “I personally protest against the sale of a woman’s goods to pay taxes over which she has no control.” When the sale began that afternoon, the crowd and the hubbub had become so intense that the first thing the auctioneer did was to reassure people that it really was an auction they were attending.

Kate Harvey then addressed the crowd and explained why she was resisting (“Simply and solely because she was a woman… she had no voice in saying how the taxes collected from her should be spent.”)

The tax collector suffered this speech in silence, but he could judge by the cheers it received that there were many ardent sympathisers with Mrs. Harvey in her protest. He tried to proceed, but one after another the men present loudly urged that no one there should bid for the goods. The tax-collector feebly said this wasn’t a political meeting, but a genuine sale! “One penny for your goods then!” was the derisive answer. “One penny—one penny!” was the continued cry.…

The din increased every moment and pandemonium reigned supreme. During a temporary lull the tax-collector said a sideboard had been sold for nine guineas. Angry cries from angry men greeted this announcement. “Illegal sale!” “He shan’t take it home!” “The whole thing’s illegal!” “You shan’t sell anything else!” and The Daily Herald Leaguers, members of the Men’s Political Union, and of other men’s societies, proceeded to make more noise than twenty brass bands. Darkness was quickly settling in; the tax-collector looked helpless, and his deputy smiled wearily. “Talk about a comic opera—it’s better than Gilbert and Sullivan could manage,” roared an enthusiast. “My word, you look sick, guv’nor! Give it up, man!” Then everyone shouted against the other until the tax-collector said he closed the sale, remarking plaintively that he had lost £7 over the job! Ironical cheers greeted this news, with “Serve you right for stealing a woman’s goods!” He turned his back on his tormentors, and sat down in a chair on the table to think things over. The protesters sat on the sideboard informing all and sundry that if anyone wanted to take away the sideboard he should take them with it! With the exit of the tax-collector, his deputy and the bailiff, things gradually grew quieter, and later on Mrs. Harvey entertained her supporters to tea at the Bell Hotel. But the curious thing is, a man paid nine guineas for the sideboard to the tax-collector. Mrs. Harvey owed him more than £17, and Mrs. Harvey is still in possession of the sideboard!

Example The American War Tax Resistance Movement

Section titled “ The American War Tax Resistance Movement”There have been a few celebrated auction sales in the American war tax resistance movement. Some were met with protests or were used as opportunities for outreach, but others have been more actively interfered with.

When Ernest and Marion Bromley’s home was seized, for example, there were “months of continuous picketing and leafletting” before the sale. Then:

The day began with a silent vigil initiated by the local Quaker group. While the bids were being read inside the building, guerilla theatre took place out on the sidewalk. At one point the Federal building was auctioned (offers ranging from 25¢ to two bottle caps). Several supporters present at the proceedings inside made brief statements about the unjust nature of the whole ordeal. Waldo the Clown was also there, face painted sadly, opening envelopes along with the IRS [Internal Revenue Service] person. As the official read the bids and the names of the bidders, Waldo searched his envelopes and revealed their contents: a flower, a unicorn, some toilet paper, which he handed to different office people. Marion Bromley also spoke as the bids were opened, reiterating that the seizure was based on fraudulent assumptions, and that therefore the property could not be rightfully sold.

These protests, odd as they were, eventually paid off. Around the same time that this auction was taking place, the IRS was caught improperly pursuing political dissidents. As the scandal broke the agency decided to reverse the sale of the Bromley home and to give up on that particular fight.

When Addie and Paul Snyder’s home was auctioned off for back taxes, “many bids of $1 or less were made.” A newspaper article on the auction noted:

Making a bid of pennies for farm property being foreclosed for failure to meet mortgages was a common tactic among angry farmers during the Depression. If their bids succeeded, the property was returned to its owner and the mortgage torn up. In some such cases, entire farms plus their livestock, equipment, and home furnishings sold for as little as $2.

When Randy Kehler and Betsy Corner’s home was put up in a sealed-bid auction, “The IRS received close to 100 bids, but none was monetary.” Bids included a package of community service pledges and food for the poor, massages or psychotherapy for IRS employees, free dental work for IRS employees, nonviolence training sessions, and “42 blocks of ice, to symbolize the end of the 42-year Cold War.” The tax agency rejected all the bids.

You don’t need to disrupt the auction itself in order to frustrate the tax authorities. The seizure and auctioning of a resister’s property is meant to be punitive and discouraging, so if you can instead make it celebratory and encouraging you disrupt the auction even if it otherwise proceeds as normal. When the IRS seized George and Lillian Willoughby’s car to recover about $100 in refused telephone excise tax, the Willoughbys’ friends and supporters raised what they called a “peace bond” of money so they could buy the car back at auction—and they donated the extra money from the “bond” to the local war tax resistance group. George Willoughby remembers: “One IRS official complained, ‘here we seize your car to raise money for the IRS, and you are using it to raise money for your cause!’ ”

Example Reform Act Agitation

Section titled “ Reform Act Agitation”During the tax resistance that accompanied the drive to pass the Reform Act in the early 1830s in the U.K., hundreds of people signed pledges in which they declared that “they will not purchase the goods of their townsmen not represented in Parliament which may be seized for the non-payment of taxes.” A news account asserted:

The tax-gatherer… might seize for them, but the brokers assured the inhabitants that they would neither seize any goods for such taxes, nor would they purchase goods so seized. Yesterday afternoon, Mr Philips, a broker, in the Broadway, Westminster, exhibited the following placard at the door of his shop:—“Take notice, that the proprietor of this shop will not distrain for the house and window duties, nor will he purchase any goods that are seized for the said taxes; neither will any of those oppressive taxes be paid for this house in future.”

And another said:

A sale by auction of goods taken in distress for assessed taxes was announced.… From forty to fifty persons attended, including some brokers, but no buyer could be found except the poor woman from whose husband the goods had been seized, and the auctioneer himself. A man came when the sale was nearly over, who was perfectly ignorant of the circumstances under which it took place, and bid for one of the last lots; he soon received an intimation, however, from the company that he had better desist, which be accordingly did. After the sale was over nearly the whole of the persons present surrounded this man, and lectured him severely upon his conduct, and it was only by his solemnly declaring to them that he had bid in perfect ignorance of the nature of the sale that he was suffered to escape without some more substantial proof of their displeasure.

Example Railroad Bond Shenanigans

Section titled “ Railroad Bond Shenanigans”There was an epidemic of fraud in the United States in the late nineteenth century in which local jurisdictions were convinced to issue bonds to pay for the railroad to come to town. The railroad never arrived, but the citizens then were on the hook to tax themselves to pay off the bond-holders. Many groups of citizens refused, but by then the bonds had been sold to people who were not necessarily involved in the original swindle but who had just bought them as investments, and who filed lawsuits to compel payment.

Auctions were sometimes disrupted in the course of the tax resistance campaigns associated with these railroad bond boondoggles. Here are two examples:

St. Clair [Missouri]’s taxpayers joined the movement in the 1870s to repudiate the debts, but the county’s new leaders wanted to repay the investors. Afraid to try taxing the residents, they decided to raise the interest by staging a huge livestock auction in 1876, the proceeds to pay off the railroad bond interest. On auction day, however, “no one seemed to want to buy” any animals. To bondholders the “great shock” of the auction’s failure proved the depth of local resistance to railroad taxes.

Another attempt was made… and another failure has followed. The scene was upon the farm of William Atkins, where 200 of the solid yeomanry of the town had assembled to resist the sale… A Mr. Updyke, with broader hint, made these remarks: “I want to tell you folks that Mr. Atkins has paid all of his tax except this railroad tax; and we consider any man who will buy our property… as contemptible sharks. We shall remember him for years, and will know where he lives.” The tax collector finally rose and remarked that in view of the situation he would not attempt to proceed with the sale.

Example The White League in Louisiana

Section titled “ The White League in Louisiana”In Reconstruction-era Louisiana, a mob of white supremacist tax resisters disrupted a tax auction. One struck the auctioneer when he attempted to sell distrained property, and dozens of others, armed with revolvers, backed him up. As a result:

…very few people attended tax-sales [typically], because the white people were organized to prevent tax-collection, and pledged themselves not to buy any property at tax-sales, and the property was generally bought by the State.

Example Piet Bezuidenhout’s Wagon

Section titled “ Piet Bezuidenhout’s Wagon”The First Boer War erupted in the aftermath of the successfully resisted auction of a tax resister’s wagon. The Boers had been paying taxes to the British reluctantly, but the British brazenly used this reluctant compliance as evidence that the Boers were content under British rule. Infuriated, Boer separatists declared they would refuse to pay or would only pay under protest. The British criminally charged the publisher of a Pretoria newspaper for having printed such tax resistance vows.

The British government took Piet Bezuidenhout to court to try to force him to pay about twice the amount of taxes as was actually lawfully due. Bezuidenhout offered to pay the actual amount due under protest—an offer the court eventually accepted, but only after adding court costs that brought the total back up to exactly the inflated amount the government had originally asked for. Bezuidenhout, unwilling to be swindled in this way, refused to pay.

The government then seized his wagon and attempted to auction it off, but a hundred armed Boers stormed the auction, assaulted the sheriff who was to conduct the sale, and hauled the wagon away. When the government raised a squadron of police to try to recapture Bezuidenhout, the Boers assembled a small army to resist this attempt. Realizing they had forced matters to a head, the Boers declared independence and decided to fight it out.

Example Great Depression in the U.S.

Section titled “ Great Depression in the U.S.”Farmers in many states of the United States united to prevent auctions of properties foreclosed for delinquent taxes. One account read:

Wherever mortgage sales were scheduled, farmers prepared to meet in a body, and, after bidding in the property at penny prices, return it to the owner. In several instances, nooses were suspended from barns and trees near the auction block as sinister warnings to outsiders who might plan to raise the bids.

Delinquent tax sales, scheduled in Iowa yesterday, were postponed for the second time because of absence of bidders. Groups of farmers prevented bidding as a strategic method of preventing sales.

Example Poll Tax Rebellion

Section titled “ Poll Tax Rebellion”During the Poll Tax rebellion, occasionally agents would try to seize and auction off items from the homes of resisters. The resistance campaign advised people to call for help:

All you have to do is contact, the same day or as soon as possible when you get the four days written notice necessary, your local Anti Poll Tax Group and we will rally a huge task force to physically stop any Poinding taking place. Every threatened Poinding so far (Non-Registration) has been defeated by a human wall of defiant resistance.

Notes and Citations

- “The non-conformists in the English town…” The Daily Saratogian 28 May 1892, p. 4

- “Difficulty is experienced everywhere…” San Francisco Chronicle 19 October 1903, p. 6

- “The Passive Resistance of Edinburgh, to the Clergy-Tax” Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine September 1833, pp. 795–802

- Report from the Select Committee on the Edinburgh Annuity Tax Abolition Act (1866) pp. 88, 151

- Fitzpatrick, William John The Life, Times, and Correspondence of the Right Rev. Dr. Doyle, Vol. II (1862) pp. 404–05

- “Cork” The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, 13 October 1832, p. 3

- “The Tithe Riots in Wales” Spectator 4 June 1887

- Gilbert, Morris “Europe Day By Day” New York Evening Post 22 October 1931, p. 13

- “British Farmers Rebel Against Centuries-Old ‘Church Taxes’ ” Sherbrooke Daily Record 3 October 1933, p. 6

- “Tithe Payments” [Horsham] Times 18 September 1931, p. 4

- “Tithe Rents” [Townsville] Daily Bulletin 26 September 1931, p. 7

- “Trouble at Tithe Sale” Barrier Miner 14 November 1931, p. 6

- “Tithe Sales in England” Barrier Miner 17 November 1931, p. 4

- “Battle of Tithes” The Brisbane Courier 22 August 1933, p. 17

- The [Hobart] Mercury 14 December 1934, p. 13

- “Poor Rates” Waterford Mail 15 March 1843

- “Other Resisters: The Growing Movement” The Vote, 15 June 1912, p. 134

- “Tax Resistance” The Vote, 15 July 1911, p. 149

- “Tax Resistance Protest” The Vote, 31 August 1912, pp. 327–8

- Andrews, Constance E. “Tax Resistance” The Vote, 11 April 1913, p. 396

- “Tax Resistance” The Vote, 15 July 1911, p. 149

- “Tax Resistance” The Vote, 16 March 1912, p. 250

- “The Sale That Was Not a Sale” The Vote, 5 December 1913, p. 86

- “Peacemakers Resist IRS Attack” Peace Newsletter (Syracuse Peace Council), September 1975, p. 4

- “Newaygo Group Tries to Thwart Sale of Protester’s Property for Back Taxes” The Argus-Press, 19 March 1975, p. 6

- Hedemann, Ed War Tax Resistance (2003) p. 107

- “In This Corner” The Cuba Patriot 6 June 1990, p. 1

- Deming, Vinton “Finding Affinity” Friends Journal March 1992, p. 2

- Ettel, Herb “Bound by a Common Humanity: The Willoughbys at 75” Friends Journal Sept. 1990, pp. 21–25

- “Provincial Occurrences” The New Monthly Magazine and Literary Journal, 1 December 1831, p. 549

- “Whig Prosecutions of the Press” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, March 1834, p. 300

- “The Country” The Spectator No. 254 (11 May 1833), p. 422

- Thelen, David R. Paths of Resistance: Tradition and Dignity in Industrializing Missouri (1986), p. 68

- “Tax Resistance in Steuben County” Utica Morning Herald, 3 May 1878

- “Condition of the South” Index to Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives for the Second Session of the Forty-Third Congress (1875), pp. 347–51

- “Farmers Resist Selling of Land for Back Taxes” News-Herald [Franklin and Oil City, Pennsylvania] 3 February 1933

- “Advice For Non-Payers” Refuse and Resist #2, January–February 1990, p. 4