Redirect Resisted Taxes to Charity

Governments devote a lot of effort—and enlist a horde of political scientists and pundits and other such clergy—to convince their subjects that paying taxes is not only mandatory, but that it’s honorable, dignified, and even charitable, while failure to pay taxes is underhanded, shady, and selfish.

Governments and other critics of tax resistance are quick to deploy this already-available propaganda lexicon in their counterattacks. They criticize tax resisters as freeloaders who enjoy the benefits of organized society without helping to fund them—as self-interested, anti-social tax evaders.

One way resisters counter this attack is by staging giveaways of their resisted taxes. This makes it clear that the resisters do not have merely selfish motives for resisting, and also demonstrates that the money is being spent for the benefit of society (and to a greater extent than if the money had been filtered through the government first).

This sort of tax redirection also can forge or strengthen ties between the resisters and the recipients, and can make more people aware of tax resistance as an option.

Examples War Tax Resisters

Section titled “ War Tax Resisters”This tactic is put to particularly good use by the contemporary war tax resistance movement. Here are some examples:

When Julia “Butterfly” Hill refused to pay more than $150,000 in taxes to the U.S. government in 2003, she made a point of saying “I ‘redirect’ my taxes rather than ‘resisting’ my taxes”:

I actually take the money that the IRS [Internal Revenue Service] says goes to them and I give it to the places where our taxes should be going. And in my letter to the IRS I said: “I’m not refusing to pay my taxes. I’m actually paying them but I’m paying them where they belong because you refuse to do so.” They are not directing our money where it should be going, they are being horrific stewards of that money.

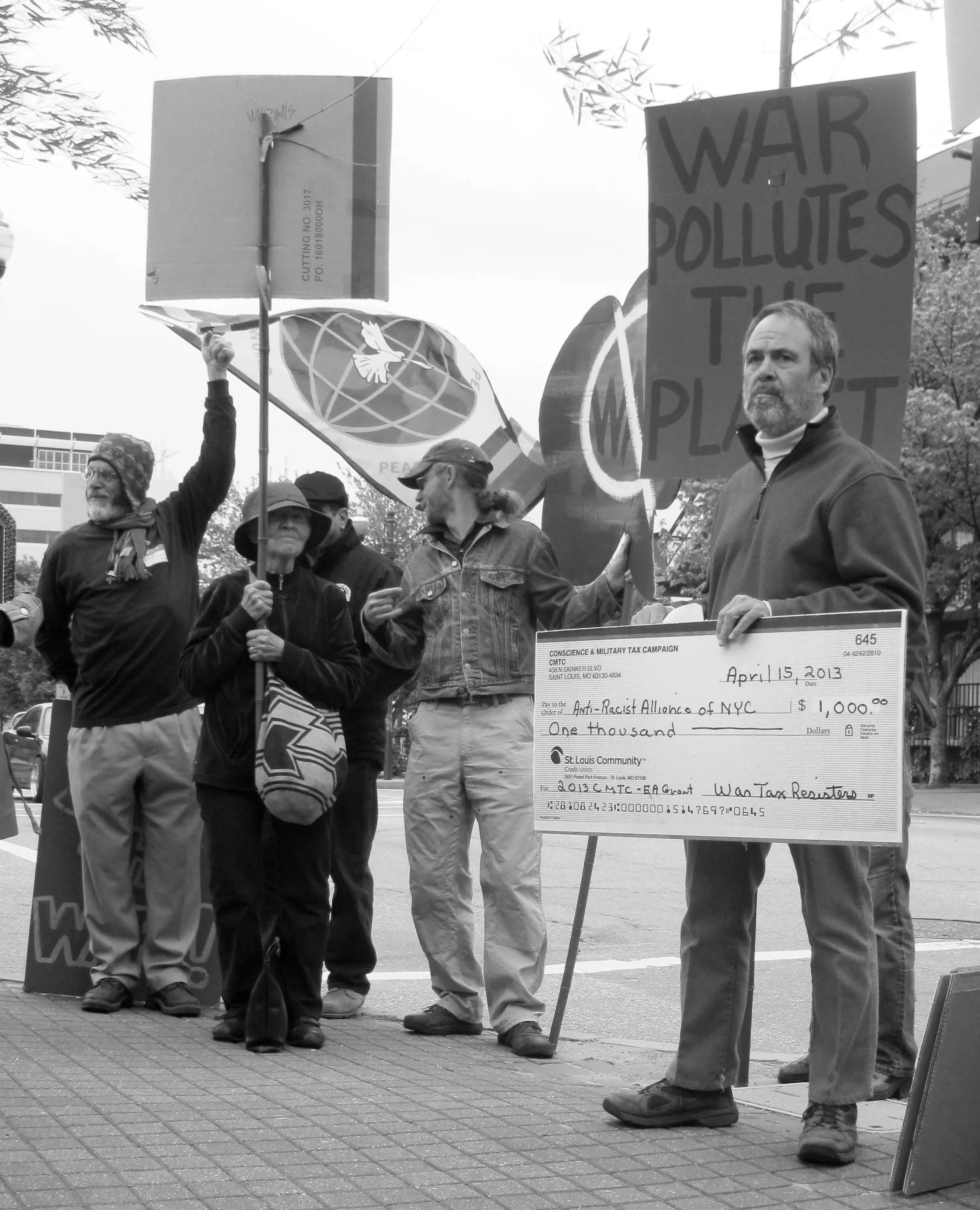

The National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee (NWTRCC) organized what it called a “War Tax Boycott” in 2008. It encouraged war tax resisters across the country to coordinate by redirecting their refused taxes to either of two groups: one that provided healthcare in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, and one that helped Iraq War refugees. The campaign kept track of how much money had been redirected over the course of the boycott, and then held a press conference to give oversized checks adding up to about $325,000 to spokespeople for these campaigns.

The People’s Life Fund is associated with the group Northern California War Tax Resistance, and holds redirected taxes from resisters. If the IRS successfully seizes money from a resister, that resister can reclaim his or her deposits to the Fund. Otherwise, the money remains there and earns interest and dividends. Every year the group pools these returns on investment and gives them away to local charitable organizations in a granting ceremony. Usually these grants are modest—$2,000 to $5,000 each—but they give them to a dozen or more groups, which makes their granting ceremonies a good way for local charities to network with each other and helps spread the word about war tax resistance in the local activist community.

This same model, or one similar to it, is followed by a number of regional redirection funds associated with war tax resistance groups in the United States. A war tax resistance group in Iowa used the proceeds from its redirection fund to create a scholarship for college students who had been banned from applying for government financial aid because of their refusal to register for the military draft. Another, in Pennsylvania, made an interest-free loan to a legal defense group that was supporting a group of draft resisters who were on trial. These actions helped to forge or sustain ties between the war tax resistance movement and anti-conscription activists and gave war tax resistance a higher profile in the larger anti-war movement.

One family figured out a way to get extra mileage out of their redirection: In 1997 they redirected their refused federal taxes to a charitable program called “Childreach.” That year, the U.S. Agency for International Development, a federal government agency, had promised to match private donations to Childreach two-to-one from its budget, so the family’s $211.69 in redirected taxes had the effect of pulling an additional $423.38 from the U.S. government for a good cause.

In 1968, war tax resister Irving Hogan stood outside the Federal Building in San Francisco and redirected his federal income tax dollars one at a time by handing them out to passers by. “I want this money to be used for the delight, not the destruction, of men,” he said. “Here: go buy yourself a beer.”

John and Pat Schwiebert did something similar: They redirected their taxes by handing out five-dollar bills to people standing in line at the unemployment office. Attached to the bills were leaflets in which they explained their redirection action. To amplify the public relations impact, they notified the media of their plans ahead of time. “Their actions garnered them an interview on NPR,” according to one report, “and they received letters and cards from around the world.”

In 1972 a group of war tax resisters in New York redirected their war taxes as nickels that they handed out to people waiting at the bus stops on lines where fare hikes were being proposed, saying “this is where our tax dollars should be going.”

On April Fools’ Day in 1983, some Christian war tax resisters in Virginia released 75 helium balloons with five- and ten-dollar bills tied to them, along with a note:

About 60 percent of your income tax money this year will be used to pay for our government’s military program. Because we are Christians who are trying to follow the peaceful way of Jesus, we cannot support this country’s military build-up. Instead we have chosen to waste our money in a more constructive way.

On this Good Friday we remember the crucifixion of Jesus Christ each time one nation or individual inflicts violence on another. On this April Fool’s Day we release our money into the wind—it is not as foolish an act as depending on weapons for our security.

We are confident that you, the finder, will be able to use this money in a better way than the Pentagon would have. Peace be with you!

Arthur Evans felt that if redirecting your war taxes to charity is a good idea, redirecting twice your war taxes to charity must be twice as good. In 1965 he wrote to the IRS to tell them “I am sending double the amount I am not paying for war to Quaker House at the United Nations for transmission to the United Nations Organization for its technical assistance program.”

In the early 1970s, farmers who were resisting the expansion of a military base onto their land in Larzac, France, found common cause with war tax resisters. Thousands of war tax resisters there redirected their war taxes to help fund the Larzac struggle.

In 1971, a Mennonite pastor hit upon a clever way to include IRS personnel in his tax redirection. When he filed his taxes, he included two checks: one made out to the government for the portion of his taxes he was not objecting to, and another check made out to the Mennonite Central Committee for the portion that he felt supported the government’s war budget. He included a stamped, addressed envelope with which the IRS could forward the second check to its intended destination, and a letter explaining his action. The IRS forwarded the second check as he requested.

And here’s something kind of similar that doesn’t fit into any of my other categories, so I’ll toss it in here: When the IRS seized back taxes from war tax resister Mary Regan’s retirement account in 1998, she threw a fund-raising party to try to raise an equivalent amount of money—but not in order to reimburse her, but to give away to charities like “the Boston Women’s Fund, the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Friends Service Committee, a homeless shelter for youth, and the peace movement in Israel.”

Example British Women’s Suffrage Movement

Section titled “ British Women’s Suffrage Movement”The Women’s Tax Resistance League largely suspended its campaign during World War I, but one woman, who signed her letter “A Persistent Tax Resister,” wrote to the editor of a suffragist paper to suggest that women should redirect their taxes from the government to a privately-run war relief charity “and should send her donation as ‘Taxes withheld from the Government by a voteless woman.’ ” Suffrage activist Charlotte Despard reported that “she had offered to give voluntarily the amount demanded of her by Revenue authorities to any war charity, but her offer had not been accepted.”

Example Social Security Foe

Section titled “ Social Security Foe”In 1952, Howard Pennington, unwilling to pay an $81 social security tax “for waste by socialistic dreamers,” instead sent that money directly to George Robinett. Robinett was a 72-year-old retiree whose social security had been abruptly cut off for three months, costing him $210, because during one month he had earned 62 cents above the $50 maximum monthly earnings for a social security recipient.

Example Education Rate Resisters

Section titled “ Education Rate Resisters”People who resisted taxpayer-funded sectarian education in the U.K. in the early 20th century would often try to pay their taxes minus a fraction that could be attributed to the offensive education rate. This would assuage their consciences while forcing the government to engage its cumbersome tax enforcement apparatus over a paltry amount of money.

Sometimes anonymous people would instead pay these small amounts on behalf of the resister, thereby spoiling their resistance (and perhaps casting doubt about whether they had really resisted at all).

To try to discourage enemies of the movement from interfering in this way, resisters declared publicly that if anyone donated money to satisfy their resisted taxes, they would in turn donate the same sum to the Passive Resistance League which was organizing the tax resistance.

Notes and Citations

- When I presented some of my ideas about varieties of tax resisters (see “Varieties of Tax Resister”) at the Spring 2013 NWTRCC national conference, some of those who heard my presentation suggested to me that a fifth variety of war tax resisters are primarily motivated by the desire to spend their money for the public good, and that they resist taxes because they see taxation as obstructing this aim, and careful tax redirection to be a much better way of accomplishing it. It’s worth noting that while redirection is a powerful tool for public relations, to its practitioners, it is usually much more than this.

- Smith, Gar “An Interview with Julia Butterfly Hill: Part 1” The Edge 26 May 2005

- Hanrahan, Clare “War Tax Boycott Redirection” More Than a Paycheck June 2008, p. 1

- “Scholarships for draft evaders” Utica Sunday Observer-Dispatch 6 May 1984 p. 4A

- “ ‘War tax’ resisters provide loan” Delaware County Daily Times 5 February 1973, p. 4

- “Matching Funds” More Than a Paycheck October 1997

- “ ‘War’ Tax Resister Gives Joy To Some” (United Press International) Binghamton Press 16 April 1968, p. 12A

- Balzer, Susan “NWTRCC Strategy Conference” More Than a Paycheck December 2005, p. 1

- Squire, DeCourcy “Journeys Begin with the First Step” More Than a Paycheck August 2009, p. 1

- Hochstetler, Clair “Money wasted on Good Friday” Gospel Herald 19 April 1983, p. 281

- Evans, Arthur “A Quaker Physician’s Tax Stand” Friends Journal 15 August 1965, p. 411

- Simpson, Craig “An International View” Friends Journal 15 February 1976, pp. 111–12

- “Pastor enlists Internal Revenue Service in protest” The Mennonite 21 September 1971, p. 557

- “WTR Matches IRS Levy for Good Causes” More Than a Paycheck February 2009

- “Tax Resistance” The Vote 11 September 1914, p. 311

- “Meeting at the Women’s Freedom League Headquarters” The Vote 9 February 1917, p. 109

- “Money Owed U.S. Given To Oldster” (Chicago Tribune Service) The Spokesman-Review 13 March 1952, p. 1

- Portsmouth Evening News 3 March 1904 (education rate resisters)